Introduction. The diagnosis of malignant ascites is a challenging problem in clinical practice, non-invasive techniques should be developed to improve diagnostic accuracy. The diagnostic performances of tumor markers in malignant ascites remained unsettled. Our aim was to evaluate diagnostic performance of tumor markers in differential diagnosis of benign and malignant ascites.

Material and methods. A total of 437 patients were enrolled, and the relevant parameters of the patients were analyzed for the differentiation of benign ascites from malignant ascites.

Results. At the predetermined cutoff values of tumor makers, tumor markers in ascitic fluid showed better diagnostic performance than those in serum. Combined use of tumor markers and the cytology increased the diagnostic yield of the latter by 37%. In cytologically negative malignant ascites, tumor markers provided assistance in differentiating malignant ascites from benign ascites, and the combination of ascitic tumor markers yielded 86% sensitivity, 97% specificity.

Conclusion. Use of a panel of tumor markers exhibited excellent diagnostic performance in diagnosing malignant ascites, which indicated the detection of tumor markers may represent a beneficial adjunct to cytology, thus guiding the selection of patients who might benefit from further invasive procedures.

Ascites is the pathological accumulation of fluid within abdominal cavity, which is commonly associated with chronic hepatic diseases, malignant neoplasia, cardiac insufficiency, tuberculous peritonitis, renal diseases and etc.1,2 Ascites presents a challenging diagnostic problem for gastroenterologists because of the lack of specific and sensitive differential diagnostic strategies. Malignant ascites accounts for about 10% of all cases of ascites and commonly associated with gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, hepatobiliary, ovarian, endometrial, primary peritoneal carcinomas.3,4 In clinical practice, complete separation between malignant ascites and benign ascites has not been always possible. Cytology for malignant ascites is an important diagnostic tool due to its high specificity, but positive results are obtained only in 40-60% of cases.5–7 Peritoneal biopsy upon laparoscope provides an alternative diagnostic strategy for malignant ascites.8,9 But its application is limited in clinical practice because this procedure is not available at all facilities and may be too invasive for the patients. Therefore, other non-invasive techniques should be developed for the differentiation between malignant ascites and benign ascites.

Tumor markers are produced directly by the tumor or by non-tumor cells as a response to the presence of a tumor, which offers a putative clinical use in the screening, diagnosis and treatment of various cancers. Thus, numerous studies demonstrated the detection of serum or ascitic tumor markers was helpful in differentiating malignant ascites from benign ones;5,7,10–18 their diagnostic value was still debated because a relatively small sample of the patients or individual markers involved confined their clinical value. Therefore, the diagnostic value of tumor marker in malignant ascites remained unsettled.

In the present study, the aims of our study were:

- •

To evaluate diagnostic value of a panel of tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 15-3 (CA 15-3), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and CA-125 in diagnosing malignant ascites.

- •

To evaluate diagnostic value of tumor markers in cytologically negative malignant scites.

- •

To assess their usefulness as differential diagnostic markers among different types of cancers.

In this study, we collected 437 patients with the ascites at Union Hospital and Tongji Hospital affiliated to Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University from 2007 to 2012. All the patients had undergone diagnostic paracentesis with the measurement of several parameters. The parameters included cytological examination and a panel of tumor markers. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee of the participant centers.

Diagnostic criteriaThe causes of ascites were determined by well-established clinical criterion. The patients were classified into two groups named as benign and malignant ascites according to the etiology. The benign group consisted of two groups: portal hypertension and non-portal hypertension. Portal hypertension was defined by clinical manifestation of ascites, esophageal and gastric varices, and splenomegaly, which were confirmed by using clinical assessment, laboratory findings, imaging data and/or histological examination. In this study, the causes of ascites resulted from portal hypertension included liver cirrhosis, cardiac insufficiency, Budd-Chiari syndrome, veno-occlusive disease. The etiology for benign ascites without portal hypertension included tuberculous peritonitis, pancreatic ascites, nephrotic syndrome, connective tissue disease, secondary bacterial peritonitis. Malignant ascites was defined in the patients with positive cytology of ascitic fluid; in addition, the patients with negative ascitic cytology finding were diagnosed as malignant ascites when the patients had a known primary malignancy after ruling out benign causes of the ascites. The diagnosis of malignant ascites caused by primary liver cancer was based on tumor localization as confirmed by CT, MRI or liver biopsy after ruling out the metastasis of gastrointestinal malignancies. In addition, low SAAG (defined as less than 1.1 g/dL) should be required for eliminating the ascites resulted from portal hypertension.

Pancreatic ascites was diagnosed when the ascitic fluid amylase level was at least twice that of the upper limit of normal (ULN) for serum amylase; in addition, pancreatic cancer should be excluded.19 Tuberculous peritonitis was defined in patients with granulomatous inflammation on peritoneal biopsy, or complete clinical and laboratory response after antituberculous therapy when exudative ascites and the exclusion of other causes. Secondary bacterial peritonitis with gastrointestinal perforation was defined by:

Tumor marker assay, and cholesterol assay cytological assayAscites samples obtained by paracentesis were collected in tubes, and then sent for biochemical assay and cytological examination. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 12-5 (CA12-5), CA19-9, CA15-3, alpha-feto-protein (AFP) and prostate specific antigen (PSA) were measured in serum and ascitic fluid according to instruction manual using chemiluminescence microparticle immuno assay (Fujirebio Diagnostics Inc, Malvern, PA 19355,USA). Serum CEA, CA 12-5, CA15-3, and CA199 levels of 5 ng/mL, 35 U/mL, 31 U/mL, and 37 U/mL, respectively, were adopted as the upper limits of normal in healthy subjects.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 13.0). Data of the quantitative studies were expressed as mean ± SD. Independent-samples T test was used for the analysis of differences between the two groups. Differences were considered significant for P < 0.05.

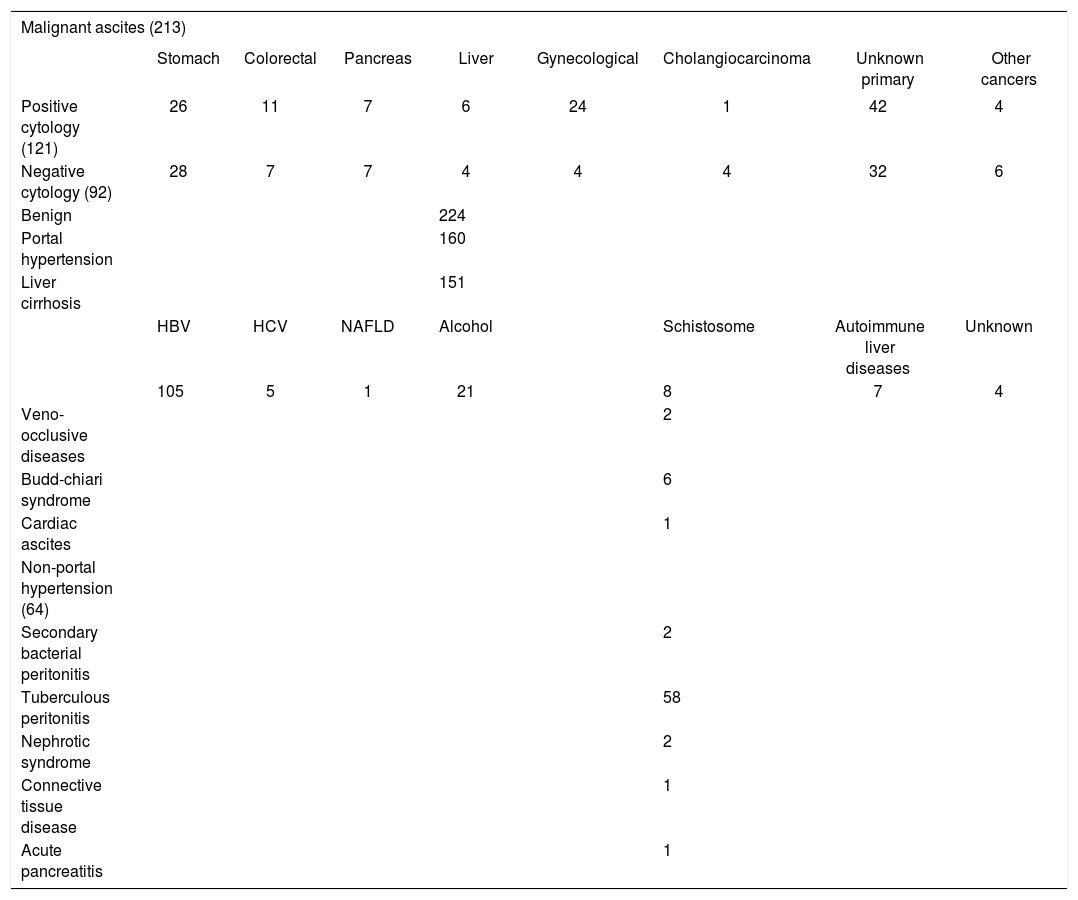

ResultsEtiology of ascitesIn this study, the study population consisted of 437 patients was divided into two groups: benign ascites and malignant ascites. Two-hundred twenty-four patients had a benign ascites, 160 patients had ascites associated portal hypertension, 64 patients with ascites of non-portal hypertensive etiology. Among malignant group, there were 121 patients with positive fluid cytology findings, and 92 patients with cytology-negative ascites. The specific etiologies and the histological subtypes of tumors were presented in Table 1. For cytologically-positive malignant ascites, malignant ascites with unkown primary carcinoma (Table 1) referred to the patients with unspecified origin. For cytologically-negative malignant ascites, a diagnosis of unspecified primary was made in the patients with a known malignancy which involved two or more organs after ruling out other causes. It was confirmed by radiological finding and/or histological examination.

Etiology of benign and malignant ascites.

| Malignant ascites (213) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | Colorectal | Pancreas | Liver | Gynecological | Cholangiocarcinoma | Unknown primary | Other cancers | |

| Positive cytology (121) | 26 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 24 | 1 | 42 | 4 |

| Negative cytology (92) | 28 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 6 |

| Benign | 224 | |||||||

| Portal hypertension | 160 | |||||||

| Liver cirrhosis | 151 | |||||||

| HBV | HCV | NAFLD | Alcohol | Schistosome | Autoimmune liver diseases | Unknown | ||

| 105 | 5 | 1 | 21 | 8 | 7 | 4 | ||

| Veno-occlusive diseases | 2 | |||||||

| Budd-chiari syndrome | 6 | |||||||

| Cardiac ascites | 1 | |||||||

| Non-portal hypertension (64) | ||||||||

| Secondary bacterial peritonitis | 2 | |||||||

| Tuberculous peritonitis | 58 | |||||||

| Nephrotic syndrome | 2 | |||||||

| Connective tissue disease | 1 | |||||||

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | |||||||

Data are present as number in this table. Other cancers in this research were divided into two category: positive and negative cytology; positive cytology included mesotheliomas (n = 1), lung (n = 1), peritoneal serous adenocarcinoma (n = 2); negative cytology included peritoneal serous adenocarcinoma (n = 4), mesotheliomas (n = 2).

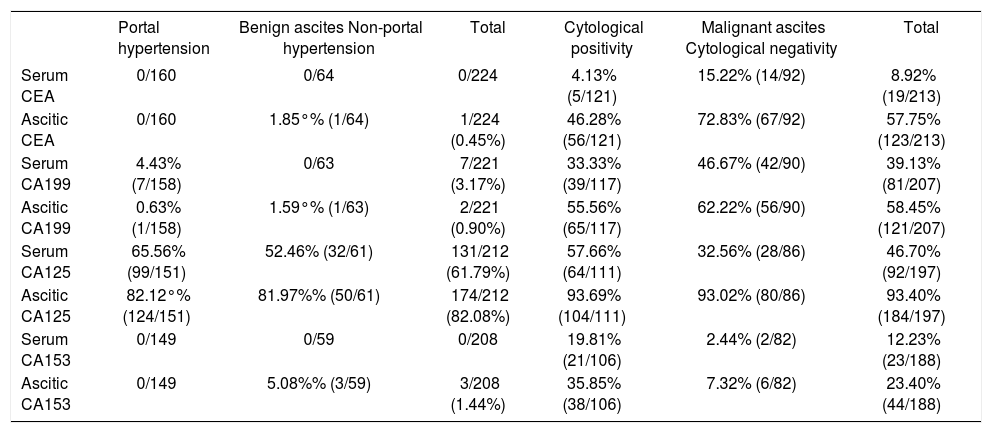

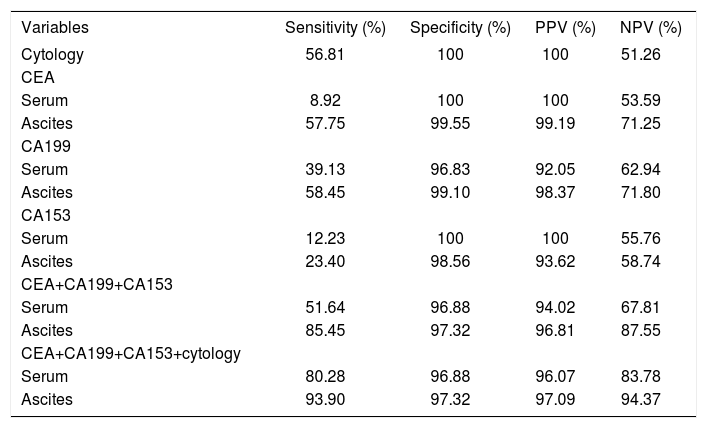

Tumor markers are the molecules, which are used in the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of various cancers. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of a panel of tumor markers in distinguishing malignant ascites from benign ascites. In order to detect the correlation of tumor markers in ascitic fluid and serum, the concentration of tumor markers in serum and ascitic fluid was detected simultaneously. Results of tumor markers in the whole population were detailed in table 2. In the study, the cutoff points for tumor markers were defined; the cutoff points were: 50 ng/mL for CEA, 200 U/mL for CA19-9, 350 U/mL for CA12-5, 75 U/mL for CA15-3. The cutoff values of tumor markers were defined according to diagnostic efficacy of and receiver operating characteristic plot (ROC) of tumor markers.22 Significant difference was noted in the percentage of serum CEA, serum CA 19-9, serum CA15-3, ascitic CEA, ascitic CA 19-9 and CA15-3; but not in serum CA 12-5 and ascitic CA12-5 between benign and malignant group (Table 2). Serum CEA and CA 153 higher than the cut-off points were specifically found in the patients with malignant ascites (Table 2). Thirty-nine percent of malignant ascites yielded a positive result in serum CA199 concentration higher than the cut-off value. Raised serum CA199 (3.17%) was also detected in a few cases of benign ascites, most of those cases had suffered from biliary calculi; fortunately, ascitic CA19-9 higher than cut-off point was not detected in those cases. As shown in table 3, the sensitivities of serum CEA, CA 19-9 and CA15-3 taken separately were 9, 39, and 12%, respectively; the sensitivities of ascitic CEA, CA 125, and CA153 were superior to that of serum tumor makers; but the specificities of ascitic tumor makers were similar to those of serum markers in malignant ascites (Table 3). It indicated that ascitic tumor markers exhibited better diagnostic performance than serum markers. In addition, we observed that diagnostic performance of CEA and CA19-9 was superior to that of CA15-3 due to higher sensitivity. In order to further evaluate diagnostic performance, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of cytology and oftumor markers, alone or in combination, were calculated (Table 3). As shown in table 3, ascitic tumor markers showed better diagnostic advantage than serum markers through the sensitivity and predictive value. Taken together, ascitic CEA, CA199 and CA153 yielded a positive result in 85% of the malignant ascites with 97% specificity. Then we evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of cytology, the results (Table 3) showed its efficacy was similar to that of ascitic CEA or CA199 alone. Finally, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of combination of cytology and tumor makers in the whole population of ascites. The combined use of cytological examination and serum markers allowed to confirm the tumoral diagnosis in 80% of malignant ascites with 97% specificity, 96% PPV, and 84% NPV; whereas the combination of cytology and ascitic markers yielded a sensitivity of 94% with a specificity of 97% in diagnosing malignant ascites. The PPV and NPV were 97% and 94%, respectively (Table 4). All these indicated that a panel of tumor markers used represented a helpful adjunct to cytology for the diagnosis of malignant ascites.

Positive rate of tumor markers at the predetermined cutoff points in benign and malignant ascites.

| Portal hypertension | Benign ascites Non-portal hypertension | Total | Cytological positivity | Malignant ascites Cytological negativity | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum CEA | 0/160 | 0/64 | 0/224 | 4.13% (5/121) | 15.22% (14/92) | 8.92% (19/213) |

| Ascitic CEA | 0/160 | 1.85°% (1/64) | 1/224 (0.45%) | 46.28% (56/121) | 72.83% (67/92) | 57.75% (123/213) |

| Serum CA199 | 4.43% (7/158) | 0/63 | 7/221 (3.17%) | 33.33% (39/117) | 46.67% (42/90) | 39.13% (81/207) |

| Ascitic CA199 | 0.63% (1/158) | 1.59°% (1/63) | 2/221 (0.90%) | 55.56% (65/117) | 62.22% (56/90) | 58.45% (121/207) |

| Serum CA125 | 65.56% (99/151) | 52.46% (32/61) | 131/212 (61.79%) | 57.66% (64/111) | 32.56% (28/86) | 46.70% (92/197) |

| Ascitic CA125 | 82.12°% (124/151) | 81.97%% (50/61) | 174/212 (82.08%) | 93.69% (104/111) | 93.02% (80/86) | 93.40% (184/197) |

| Serum CA153 | 0/149 | 0/59 | 0/208 | 19.81% (21/106) | 2.44% (2/82) | 12.23% (23/188) |

| Ascitic CA153 | 0/149 | 5.08%% (3/59) | 3/208 (1.44%) | 35.85% (38/106) | 7.32% (6/82) | 23.40% (44/188) |

Cut off points for CEA, CA19-9, CA12-5 and CA15-3 were 50 ng/mL, 200 U/mL, 350 U/mL, 75 U/mL respectively.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of cytology and tumor markers in the whole population of ascites.

| Variables | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytology | 56.81 | 100 | 100 | 51.26 |

| CEA | ||||

| Serum | 8.92 | 100 | 100 | 53.59 |

| Ascites | 57.75 | 99.55 | 99.19 | 71.25 |

| CA199 | ||||

| Serum | 39.13 | 96.83 | 92.05 | 62.94 |

| Ascites | 58.45 | 99.10 | 98.37 | 71.80 |

| CA153 | ||||

| Serum | 12.23 | 100 | 100 | 55.76 |

| Ascites | 23.40 | 98.56 | 93.62 | 58.74 |

| CEA+CA199+CA153 | ||||

| Serum | 51.64 | 96.88 | 94.02 | 67.81 |

| Ascites | 85.45 | 97.32 | 96.81 | 87.55 |

| CEA+CA199+CA153+cytology | ||||

| Serum | 80.28 | 96.88 | 96.07 | 83.78 |

| Ascites | 93.90 | 97.32 | 97.09 | 94.37 |

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of ascitic tumor markers in cytologically negative malignant ascites.

| Variables | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA | 72.82 | 99.55 | 98.52 | 89.92 |

| CA199 | 62.22 | 99.10 | 96.55 | 86.56 |

| CA153 | 7.31 | 98.56 | 66.67 | 72.95 |

| CEA+CA199+CA153 | 85.87 | 97.32 | 92.94 | 94.37 |

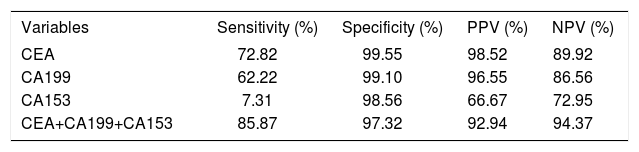

We evaluated the additional value of ascitic tumor makers in cytologically- negative malignant ascites. The positivity, specificity and predictive value of tumor markers, either individually or in combination were reported in table 4. CA 15-3, a tumor maker of gynaecological cancer, showed an inferior diagnostic performance because of low s sensitivity. The diagnostic yield of the combined three tumor markers in cytologically negative malignant effusions was 86%, with a specificity of 97% and a PPV of 92% and a NPV of 94%. The combination of three tumor markers exhibited a convincing diagnostic performance in cytologically-negative ascites.

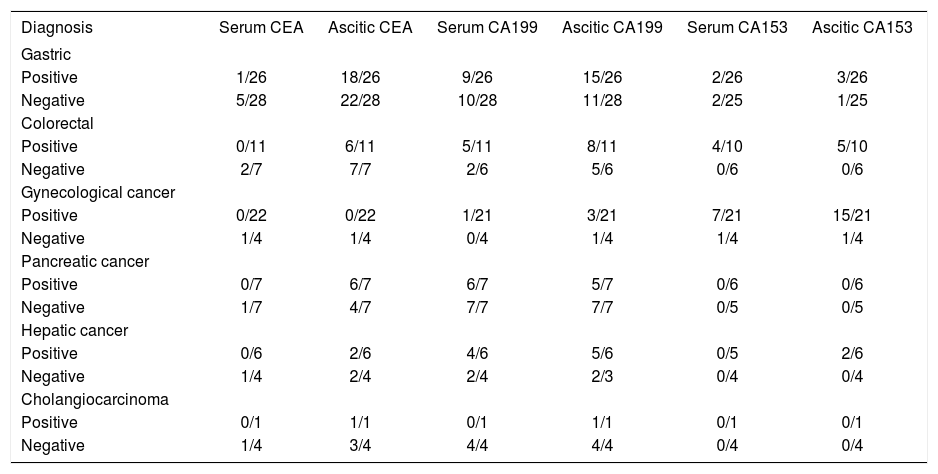

Tumor markers and tumor typesIt is well-known that some tumor markers are specific for a particular type of cancers. Therefore, we evaluated diagnostic performance of tumor markers according to the histologic type of cancer. As shown in table 5, CEA was quite effective in stomach, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, CA19-9 showed high sensitivity in pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma; whereas for gynecological cancer, CA 15-3 was specific and sensitive. On the other hand, we also detected the concentration of serum and ascitic tumor markers in order to investigate the correlations of tumor markers in ascitic fluid and serum. The patients with serum tumor markers higher than cutoff points always yielded a positive result in ascitic concentration, whereas some of the patients with positive result in ascitic tumor markers did not show elevated concentration in serum. These indicated the examination of tumor markers in ascitic fluid provided advantage over the examination of serum markers in the diagnosis of malignant ascites.

Cases showing tumor marker values higher than the cutoff value among different types of cancer with ascites.

| Diagnosis | Serum CEA | Ascitic CEA | Serum CA199 | Ascitic CA199 | Serum CA153 | Ascitic CA153 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric | ||||||

| Positive | 1/26 | 18/26 | 9/26 | 15/26 | 2/26 | 3/26 |

| Negative | 5/28 | 22/28 | 10/28 | 11/28 | 2/25 | 1/25 |

| Colorectal | ||||||

| Positive | 0/11 | 6/11 | 5/11 | 8/11 | 4/10 | 5/10 |

| Negative | 2/7 | 7/7 | 2/6 | 5/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| Gynecological cancer | ||||||

| Positive | 0/22 | 0/22 | 1/21 | 3/21 | 7/21 | 15/21 |

| Negative | 1/4 | 1/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| Pancreatic cancer | ||||||

| Positive | 0/7 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 5/7 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

| Negative | 1/7 | 4/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Hepatic cancer | ||||||

| Positive | 0/6 | 2/6 | 4/6 | 5/6 | 0/5 | 2/6 |

| Negative | 1/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/3 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | ||||||

| Positive | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| Negative | 1/4 | 3/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 |

Malignancy is an important cause of ascites; to date, cytological examination is an important technique for malignant ascites. But cytological examination using classic technique is often difficult either because of its scarceness or its delicate distinction with reactive mesothelial or inflammatory cells in effusion.21 Although invasive procedures improve diagnostic accuracy, their application is restricted because of the invasiveness and limited diagnostic efficacy. Therefore, we collected a relatively large sample consisted of 437 patients and then evaluated diagnostic performance of tumor markers for distinguishing malignant ascites from benign ascites.

Our study revealed that CEA, CA19-9 and CA15-3 were proven to be valuable in distinguishing benign ascites from malignant ascites. Among tumor makers, ascitic CEA showed the best efficacy through ROC curve (data no shown). More than half of patients with the ascites had an elevated CA12-5 higher than cut-off value. These results were consistent with previous report.22–25 It indicate that testing serum or ascite for CA12-5 is not helpful in the differential diagnosis of ascites. Therefore, we did not recommend the detection of CA12-5 in clinical practice, which is consistent with AASLD guideline.2

Tuzun, et al.16 found that tumor markers were highly correlated in serum and ascitic fluid in the malignant group and the detection of tumor markers in ascitic fluid does not have any advantage over serum analysis. Our results (Table 3) showed that diagnostic performance of tumor markers in ascitic fluid was superior to that in serum. As reported by Tuzun16 and Chen,10 mean levels of CEA were significantly higher in ascitic fluid than that in serum in the malignant group. All these demonstrated that the measurement of these markers in ascitic fluid should substitute the detection of serum markers due to better diagnostic performance of ascitic tumor markers. Therefore, the measurement of ascitic tumor markers should be recommended in clinical practice when the patients are suspected to be malignant ascites. As shown in table 3, the performance of ascitic CEA or CA199 individually was comparable to that of cytological examination; while the combination of CEA, CA19-9 and CA15-3 yielded better sensitivity (85%) and specificity (97%) compared with CEA, CA199 and CA153 alone. The addition of tumor markers to cytological analysis resulted in a 37% increase of diagnostic rate with little effect on its specificity. On the other hand, ascitic PSA and AFP were also evaluated, and the results (data not shown) showed poor performance in the diagnosis of malignant ascites because of weak positive rate and/ or the lack of specificity. Thus, a panel of tumor markers consisted of CEA, CA19-9 and CA15-3 should be determined when malignant ascites were suspected.

We also evaluated the role of ascitic tumor markers in diagnosing malignant ascites with a negative cytology. We found that the combined three tumor markers in cytologically negative malignant yielded 86% sensitivity, 97% specificity, 92% PPV of and 94% NPV. These revealed the determination of the three tumor markers exhibited a convincing diagnostic performance in cytologically-negative ascites. Therefore, we recommend to use a panel of tumor makers in the patiets who have clinical data suggestive of malignant ascites, but negative cytologic findings. Two patients of the secondary peritonitis were included in this study, one case had elevated CEA (58.4 ng/mL) in ascitic fluid. This phenomenon was reported by previous research, in which the elevations of ascitic fluid CEA or alkaline phosphatase had been shown to be accurate for detecting perforation-related secondary peritonitis.20

Despite different opinion on discriminative power of individual tumor markers, our results showed tumor makers would be helpful in identifying the origin of tumor. Elevated CEA higher than cutoff value was seen in 74% (40/54) of gastric cancer, 72% (13/18) of colorectal cancer, 71% (10/14) of pancreatic cancer, 80% (4/5) of cholangiocarcinoma respectively; raised CA19-9 higher than 200 u/mL was observed in 89% (17/19) of pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma, 37% (26/71) of gastric and colorectal cancer; 64% (16/25) of gynecological cancer exhibited CA15-3 level higher than 75 U/mL.

In conclusion, the study demonstrated that use of a panel of tumor markers exhibited excellent diagnostic performance in diagnosing malignant ascites, combined use of tumor markers and the cytology increased the diagnostic yield. In cytologically negative malignant ascites, tumor markers provided assistance in differentiating malignant ascites from benign ascites.

Thus, these indicated that detection of tumor markers may represent a beneficial adjunct to cytology in diagnosing malignant ascites.

AcknowledgmentsThe work was supported by Chinese National Clinical Key Discipline (2011-2013) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81072003 and 81270506).