Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary malignancy of the liver and represents a major global health challenge. It is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide and ranks among the fastest-rising causes of cancer deaths in many regions. In 2020, over 900,000 new cases of HCC were diagnosed globally, with nearly equal mortality, underscoring its often-late detection and poor prognosis [1]. Most cases of HCC develop in the context of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, which places HCC as both a primary malignancy and a serious complication of underlying liver disease [2]. The global epidemiology of HCC is closely linked to regional differences in the prevalence of underlying etiologies such as chronic viral hepatitis, alcohol-related liver diseases and, more recently, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, formerly NAFLD). Although hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) have historically been responsible for the majority of HCC cases in Asia and parts of Europe, their burden is changing in countries where antiviral treatment and vaccination programs have been widely implemented [3]. In contrast, MASLD is now emerging as the predominant etiology in many high-income and middle-income countries, driven by a global increase in obesity, diabetes, and sedentary lifestyles [4].

Latin America, particularly Mexico, faces a double burden of infectious and metabolic liver disease. As one of the countries with the highest prevalence of obesity and diabetes in the world, Mexico is particularly vulnerable to MASLD and its progression to cirrhosis and HCC. At the same time, liver diseases continue to be one of the main causes of loss of life years in the Mexican population [5,6]. However, nationwide epidemiological data on HCC in Mexico remain limited, most existing reports are derived from single-center studies using heterogeneous methodologies, which restricts their generalizability. Considering the changing etiological landscape, current and representative data are essential to inform clinical decision-making, improve screening strategies, and shape effective health policies. Multicenter studies in Latin America are still scarce, and few have comprehensively analyzed trends in HCC etiology, stage at diagnosis, and clinical profiles among patients with cirrhosis. This study aims to address this gap by describing the demographic, clinical, and tumor-related characteristics of HCC in cirrhotic patients across 13 tertiary referral centers in Mexico.

2Patients and Methods2.1PatientsA multicenter retrospective observational study was performed in 13 tertiary referral hospitals from different cities in Mexico: Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation (Mexico City), General Hospital of Mexico “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga” (Mexico City), Central Military Hospital (Mexico City), University Hospital “Dr. José E. González” (Monterrey), Center for Study and Research for Hepatic and Toxicological Diseases (Pachuca), General Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea González” (Mexico City), National Medical Center “La Raza” (Mexico City), ISSEMYM Medical Center (State of Mexico), National Medical Center "20 De Noviembre” (Mexico City), Institute of Medical-Biological Research (Veracruz), Hospital Christus Muguerza Faro del Mayab (Mérida), Hospital Español (Mexico City) and Juárez University of the State of Durango (Durango). The hospitals in our sample come from three geographic regions of Mexico: northern, central, and southern. These hospitals provide medical care to the Mexican population of all ages. The study was conducted from January 2018 to November 2024. The participating hospitals were selected by non-probabilistic sampling, in which physicians specialized in Gastroenterology and Hepatology from different regions of the country were invited to collaborate in the study. The inclusion of each hospital depended on the acceptance of the responsible physician to participate and register cases of cirrhosis according to the established criteria. Supplementary Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of participating hospitals.

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: they had a confirmed diagnosis of liver cirrhosis, documented by clinical findings, imaging studies and/or histopathological reports; were 20 years of age or older at the time of diagnosis; and had complete medical records for the entire period from diagnosis through November 2024. The study sample included both outpatients and inpatients, depending on the care setting of each participating center.

2.2Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis and HCCThe diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was established from a combination of clinical findings, laboratory abnormalities, and imaging features suggestive of advanced fibrosis. In most cases, cirrhosis was diagnosed noninvasively by imaging techniques such as ultrasound, liver elastography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), supported by clinical and biochemical indicators such as thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia and elevated INR. In selected cases, histological confirmation was available.

Complications of cirrhosis were assessed by focusing on portal hypertension and its manifestations. Portal hypertension was inferred from imaging evidence of splenomegaly or portosystemic collaterals, or by endoscopic identification of esophageal varices. Ascites was diagnosed by physical examination and confirmed by abdominal ultrasound; diagnostic paracentesis was performed if necessary. Esophageal varices were classified by upper endoscopy, and hepatic encephalopathy was diagnosed clinically based on neuropsychiatric symptoms in the absence of alternative causes. The presence of ascites, varices, or encephalopathy was used to classify patients as having decompensated cirrhosis.

HCC was diagnosed according to international guidelines, based mainly on dynamic imaging criteria (CT with contrast or MRI) showing hyperenhancement in the arterial phase with venous washout or in delayed phase. In selected cases, histological confirmation was available.

2.3Diagnosis of etiologyThe etiology of cirrhosis was determined based on clinical evaluation, laboratory data, imaging findings, and histopathology when available. MASLD was diagnosed in patients who met at least one of the following metabolic risk criteria: (a) BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² or waist circumference ≥ 94 cm in men and ≥ 80 cm in women; (b) HbA1c ≥ 5.7 %, previous diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus or specific antidiabetic treatment; (c) systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg or antihypertensive treatment; (d) plasma triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or hypolipidemic treatment; and (e) plasma HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL for men or < 50 mg/dL for women, or specific treatment. ALD was assigned to patients with a history of excessive alcohol consumption (≥ 30 g/day for men and ≥ 20 g/day for women). HBV-related cirrhosis was defined by the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and HCV-related cirrhosis by the presence of anti-HCV antibodies. Autoimmune liver diseases included: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), diagnosed based on elevated aminotransferases, hypergammaglobulinemia, and positivity for autoantibodies such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA); primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), characterized by a cholestatic biochemical profile and the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA); and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), defined by persistent cholestasis and typical bile duct changes on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Other causes, such as Wilson's disease, hereditary hemochromatosis, were identified using disease-specific genetic criteria. No cases were classified as cryptogenic, probably due to the updated MASLD criteria, which encompass many previously indeterminate cases.

2.4Data collectionData were systematically collected from the medical records of the 13 participating hospitals. Information was collected on patient demographics, such as age, sex, and state of origin, along with detailed etiologic data on liver cirrhosis. To assess liver function, the main laboratory findings, such as hemoglobin, platelets, creatinine, glucose, albumin, prothrombin time, INR, total bilirubin, ALT and AST, were recorded. The results of imaging tests, such as ultrasound, CT and MRI scans, along with clinical findings, such as the occurrence of HCC, portal hypertension, ascites, encephalopathy, esophageal varices and the need for liver transplantation, were also collected.

2.5Statistical analysisContinuous variables are expressed as median and range. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The chi-squared test was used to identify differences between the underlying cause of liver cirrhosis and age groups, gender, and regions, with p values <0.05 considered significant.

2.6Ethical statementsAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation (protocol code 2021-EXT-552) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

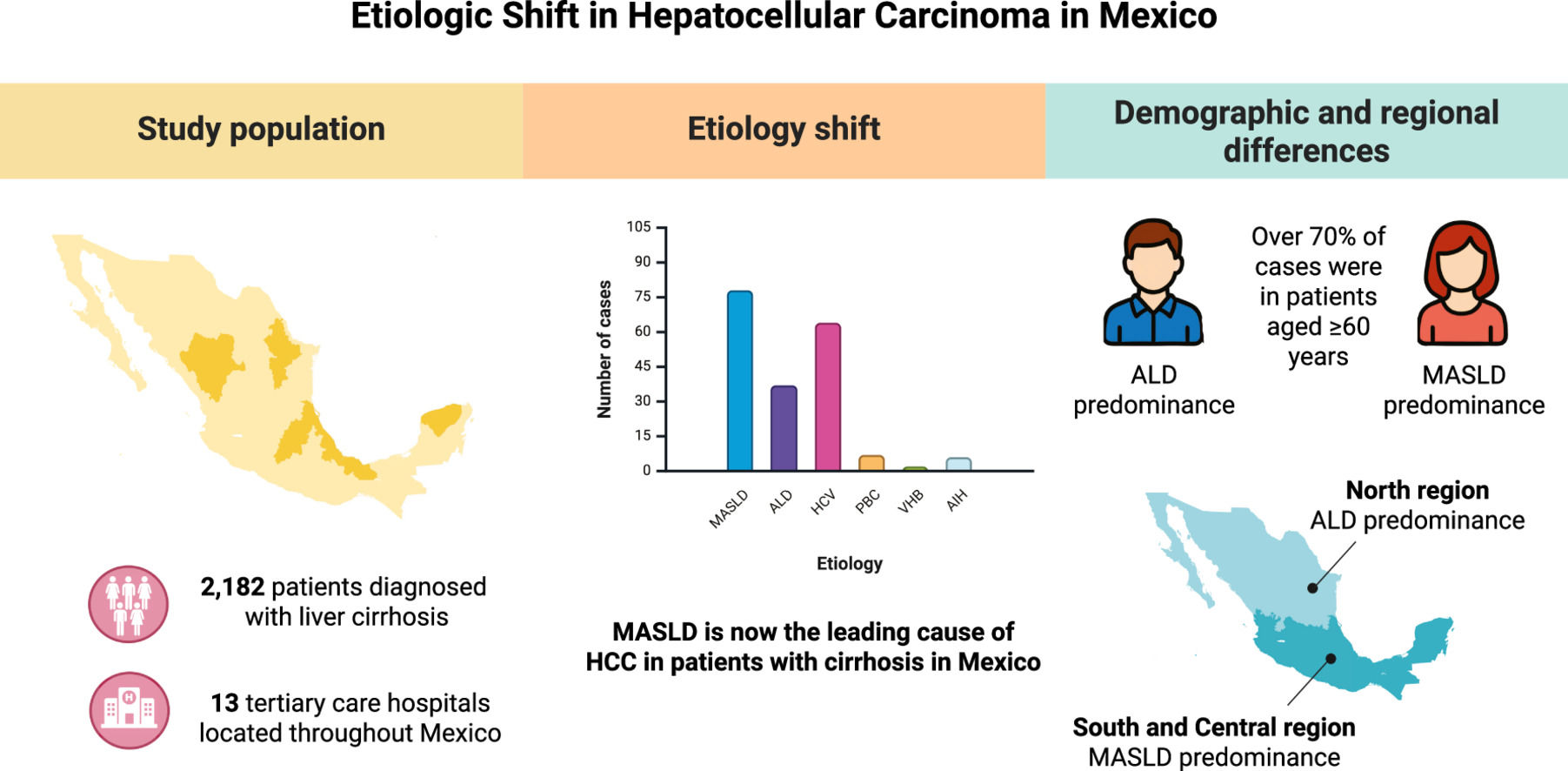

3Results3.1Population characteristicsA total of 2182 patients were included in the study. Among them, 53.8 % (n = 1174) were women and 46.2 % (n = 1008) were men, with a mean age of 58 ± 16.7 years. Geographically, most of the patients, 75.9 % (n = 1656), were from the central region of Mexico, 12.2 % (n = 266) from the northern region, and 11.9 % (n = 260) from the southern region. Of the 2182 patients, 8.8 % (n = 194) developed HCC. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the sociodemographic, and biochemical characteristics of the study population.

Sociodemographic, Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; INR, international normalized ratio.

Regional Differences in the Distribution and Etiologies of Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

AIH,autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis.

Of the 194 patients who developed HCC, 44.8 % (n = 87) were male and 55.2 % (n = 107) were female. While HCC appeared to be more prevalent in females, no statistically significant association was found between sex and HCC presence (p = 0.702). The distribution of HCC by age group showed a significant association between older age and the occurrence of HCC (p < 0.001). Patients aged 60 years or older accounted for 73.2 % (n = 145) of all HCC cases. The age group with the highest prevalence was 71–80 years, accounting for 36.6 % (n = 71) of cases, followed by 61–70 years (33.0 %, n = 64). A statistically significant linear trend (p < 0.001) further confirmed the progressive increase in the prevalence of HCC with age (Fig. 1).

Distribution of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases by age group and sex. The highest frequency of HCC was observed in individuals aged 61–80 years. A predominance of male cases was noted in the 61–70 age group, whereas female cases were more frequent in the 71–80 age group. These findings reflect the significant association between advancing age and HCC prevalence.

In the etiological distribution of HCC, MASLD was found to be the most frequent underlying etiology, accounting for 40.2 % (n = 78) of all cases, followed by HCV infection with 33.0 % (n = 64) and ALD with 19.1 % (n = 37). Among women (n = 107), the main etiology was MASLD (44.9 %, n = 48), closely followed by HCV (42.1 %, n = 45), while ALD was rare (2.8 %, n = 3). In contrast, among men (n = 87), ALD was the most frequent etiology (39.1 %, n = 34), followed by MASLD (34.5 %, n = 30) and HCV (21.8 %, n = 19). Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences in etiology according to sex. MASLD was significantly more frequent in women than in men (p = 0.035), while ALD was markedly more frequent among men (p < 0.001). HCV was also more frequent in women, with a significant difference according to sex (p = 0.002). Less frequent etiologies, such as PBC, HBV and AIH, accounted for 7.7 % (n = 15) of cases (Fig. 2).

Etiologic distribution of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) was the most common etiology overall (40.2 %, n = 78), and the predominant cause among women (44.9 %, n = 48; p = 0.035). In men, alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) accounted for the highest proportion (39.1 %, n = 34; p < 0.001), followed by MASLD (34.5 %, n = 30). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was more frequent in women (42.1 %, n = 45) than in men (21.8 %, n = 19; p = 0.002). Other less frequent etiologies were primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), which together accounted for 7.7 % of cases.

Marked regional differences were observed in both the prevalence and etiologic distribution of HCC. The central region had the highest prevalence of HCC, at 10.4 % (n = 173/1656), compared with 4.2 % (n = 11/260) in the southern region and 3.8 % (n = 10/260) in the northern region (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Etiologic patterns also varied significantly between regions. MASLD was the predominant cause of HCC in the central (40.0 %) and southern (45.5 %) regions, whereas ALD was more frequent in the north (50.0 %) and contributed substantially to the southern region (45.5 %). HCV was more frequent in the central (35.3 %) and in the northern regions (30.0 %), but no cases were identified in the south. Less frequent etiologies, such as AIH and PBC, were observed exclusively in the central and southern regions, with AIH accounting for 9.1 % of HCC cases in the south.

4DiscussionThis large multicenter retrospective study provides a comprehensive view of the evolving epidemiology of HCC in patients with cirrhosis across Mexico. Our analysis of data from 13 tertiary centers between 2018 and 2024 reveals a striking shift in the underlying etiologies of HCC, with MASLD now surpassing both ALD and chronic viral hepatitis as the most common cause. These findings reflect broader regional and global trends and underscore the urgent need to adapt liver cancer surveillance and prevention strategies to a changing disease landscape. Our data demonstrate that 40.2 % of cirrhotic patients diagnosed with HCC had MASLD as the underlying etiology. Moreover, this proportion increased markedly over the study period, from 29 % in 2018 to 52 % in 2024, while the proportion of HCC cases due to chronic HCV infection decreased [7]. Similar trends have been observed in high-income countries. In the United States, the proportion of HCV-related HCC has declined following the widespread implementation of direct-acting antivirals, and MASLD has become the leading etiology, especially among older adults and people with obesity and diabetes [8,9]. Similarly, European cohort studies report an increasing contribution of MASLD to the burden of HCC, especially in southern countries such as France and Spain, where metabolic risk factors are highly prevalent [10,11]. In contrast, in several Asian countries–including Japan and South Korea, HCV and HBV-related HCC continues to predominate, although MASLD is also increasing in parallel with urbanization and lifestyle changes [12,13]. These international patterns highlight the critical influence of regional epidemiological transitions, health system responses and population metabolic profiles on the changing etiology of HCC.

Building on these international and national trends, our stratified analyses reveal important demographic nuances. MASLD predominated among women with HCC, while ALD remained the leading cause in men, and HCV infection persisted as an important factor-particularly in women, despite its overall decline. These findings parallel data from national health surveys showing higher rates of metabolic syndrome and obesity in Mexican women, but higher alcohol consumption in men [14,15]. They suggest that sex-specific risk-factor patterns are now shaping the HCC landscape and should be reflected in tailored surveillance protocols. Age also exerted a strong influence: >70 % of HCCs occurred in patients ≥60 years, and the peak incidence shifted a decade later in women (71–80 years) than in men (61–70 years). The slower natural history of MASLD compared to viral or alcohol-related liver injury is one possible explanation, but additional biological, hormonal, and healthcare access factors may also contribute. Further research is needed to clarify these mechanisms and to determine whether extending surveillance beyond the traditional age of 70 years is warranted in MASLD-related cirrhosis [16].

Furthermore, geographic heterogeneity highlights how local exposures and health system factors modulate risk. The central region-the most urbanized and economically diverse area of Mexico-showed both the highest overall prevalence of HCC (10.4 %) and a predominance of MASLD-related cases (40 %). In contrast, the northern region, characterized by a higher per capita alcohol intake, had the highest proportion of ALD-HCC (50 %). In the south, the lower prevalence of HCC but high proportion of MASLD (45.5 %) likely reflect historically lower detection rates in addition to a rapidly increasing burden of metabolic disease. These regional patterns argue for a decentralized allocation of resources.

Our study has several important strengths. It is the largest multicenter analysis of HCC in Mexico conducted to date, covering a six-year period and involving 13 tertiary hospitals throughout the country. The use of standardized data collection protocols improves the generalizability and reliability of the findings. Our study is also one of the few in Latin America that quantifies longitudinal changes in HCC etiology, which helps to define the trajectory of liver cancer burden in this region.

However, there are limitations. Being a retrospective analysis, the study may be subject to selection and reporting bias. Data completeness varied between centers, and we lacked detailed information on certain key variables such as adherence to HCC surveillance, tumor stage and treatment outcomes. In addition, we were unable to determine whether patients had undergone periodic check-ups, which could have influenced stage at diagnosis. Differences in access to diagnostic imaging and oncologic referral pathways between centers may also have influenced tumor staging. Despite these limitations, the implications of our findings are clear. The epidemiology of HCC in Mexico is rapidly shifting toward a metabolic origin, reflecting broader societal health trends. Current liver cancer prevention and screening strategies, which have historically been tailored to viral hepatitis, need to be rethought to address the growing MASLD population. This includes improving primary prevention through obesity and diabetes control, improving noninvasive screening for fibrosis in primary care, and integrating MASLD cirrhotic patients into routine HCC surveillance programs.

5ConclusionsThis multicenter study provides the most comprehensive contemporary analysis to date of HCC in cirrhotic patients throughout Mexico. Our findings reveal a significant etiologic shift, with MASLD now emerging as the leading cause of HCC, surpassing both ALD and chronic viral hepatitis. These changes reflect broader global trends and are accompanied by marked variations by sex, age and geographic region. The predominance of MASLD among women, the persistence of ALD in men, and the delayed age of onset of MASLD-related HCC have important implications for screening strategies, which must adapt to changing risk profiles. Regional disparities in the prevalence and etiology of HCC further highlight the need for context-specific public health interventions. As the burden of metabolic liver disease continues to increase, targeted surveillance, integrated metabolic care, and sustained access to antiviral therapies will be essential to mitigate future HCC incidence and improve outcomes in at-risk populations.

FundingThis study was partially supported by Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation

Author contributionsConceptualisation: N.MS, data curation: M.RM, formal analysis: N.MS, M.RM, investigation: C.CH, E.TB, R.CO, J.MM, J.CG, M.CB, N. GR, M.GH, A.SA, E.CR, S.CH, B.BF, A.CC, J.RT, F.HDLT, J.pH, N.CT, F.VC, I.MG, R.LS, M.SH, I.BS, H.RH, N.MS, M.RM, methodology: C.CH, E.TB, R.CO, J.MM, J.CG, M.CB, N. GR, M.GH, A.SA, E.CR, S.CH, B.BF, A.CC, J.RT, F.HDLT, J.pH, N.CT, F.VC, I.MG, R.LS, M.SH, I.BS, H.RH, N.MS, M.RM, software: N.MS, M.RM validation: N.MS, M.RM, visualisation: N.MS, M.RM, writing – original draft, and writing– review & editing: N.MS, M.RM. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

None.