Chronic liver disease (CLD), such as viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), cirrhosis, and liver cancer, causes over 2 million deaths annually and 4 % of all deaths worldwide [1–5]. It is also highly disabling and among the top 10 causes of disability-adjusted life years across all disease categories, representing a substantial public health burden [6]. With the increase in alcohol consumption, global population aging, and the prevalence of metabolic disorders, CLD incidence and mortality are anticipated to escalate in the coming years [1]. Therefore, identifying modifiable risk factors is of great importance to develop prevention and intervention approaches for CLD.

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis proposes that early life, such as the prenatal period, childhood, and adolescence, is the critical window of vulnerability to environmental factors [7]. During this period, harmful exposure could permanently alter the body’s structure and physiology, resulting in long-term adverse health consequences [8]. Tobacco smoking is a dominant behavioral risk factor for premature morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have associated early-life exposure to tobacco smoke with various adverse outcomes in adulthood, such as lung cancer, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, biological aging, and dementia [9–13]. However, the effects of in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and the age of smoking initiation on the risk of CLD incidence in adulthood remain unknown. Understanding this feature may have significant public health implications given a non-negligible situation that >8 % of women in Europe smoke during pregnancy and nearly 50 million young teens globally have a history of tobacco use before the age of 15 years [14,15].

In this study, we hypothesized that early-life tobacco exposure could increase the risk of incident CLD later in life. To test the hypothesis, we extracted information from the UK Biobank cohort to quantify the associations of tobacco exposure during pregnancy and the age of smoking initiation (childhood, adolescence, or adulthood) with risks of CLD and its major subtypes in adulthood. Furthermore, we systematically explored the potential mediation effect of metabolic markers on the association between early-life tobacco exposure and CLD incidence.

2Materials and methods2.1Study design and populationThe UK Biobank is a prospective, population-based cohort of >500,000 participants aged 37–73 years recruited between 2006 and 2010 [16]. Participants attended 1 of 22 assessment centers across the UK, where they completed touchscreen and nurse-led questionnaires, had physical measurements taken, and provided biological samples. The UK Biobank study was approved by the North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 11/NW/0382) and all participants provided written informed consent. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the diagram of the analytic cohort. After excluding participants with baseline CLD and missing data on early-life tobacco exposure, a total of 429,603 participants were included in the analysis of in utero tobacco exposure and 429,180 were included in the analysis of age of smoking initiation.

2.2Assessment of early-life tobacco exposureEarly-life tobacco exposure, including in utero tobacco exposure and childhood/adolescence tobacco use, was assessed by self-reported questionnaires. Exposure to tobacco in utero was collected by this item: “Did your mother smoke regularly around the time when you were born?”, with response options of yes or no (Data-Field 1787). Participants were asked about smoking history (Data-Field 20,116), and current or former smokers were further asked the age of smoking initiation through the following items: age started smoking in current smokers (Data-Field 3436) and age started smoking in former smokers (Data-Field 2867). Then, participants were divided into four groups based on smoking status and the age of smoking initiation: never-smokers, adulthood (≥18 years), adolescence (15 to 17 years), and childhood (5 to 14 years), in accordance with previous studies [9,10].

2.3Outcome ascertainmentInformation on disease diagnoses was obtained through linkage to hospital inpatient records from the Health Episode Statistics (England and Wales) and the Scottish Morbidity Records (Scotland) and national cancer registry, based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes. The primary outcome in this study was CLD incidence, including viral hepatitis (B18-B19), NAFLD (K76.0, K75.8), fibrosis and cirrhosis (K74), ALD (K70), and liver cancer (C22) [17,18]. Individual CLD endpoints were also assessed separately. Liver enzyme levels were not used for outcome definition. Follow-up time in person-years was calculated from the baseline date to diagnosis of outcome, death, or the censoring date (March 30, 2023), whichever came first.

2.4CovariatesPotential confounders included in our analysis were as follows: age at recruitment, sex, self-reported ethnicity (White/others), birthplace (England or others), drinking status (never, previous, or current drinking), education level (university or college degree/others), Townsend Deprivation Index (TDI), physical activity, healthy diet score, prevalent diabetes (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), and body mass index (BMI) at baseline. TDI was an area-based measure of socioeconomic status derived from the postcode of residence, with a lower score indicating a higher level of socioeconomic status. Regular physical activity was defined as at least 150 min/week of moderate activity or 75 min/week of vigorous activity or an equivalent combination [19]. Healthy diet score was calculated based on the intake of fresh fruit, vegetables, fish, processed meat, and unprocessed red meat (Supplementary Table 1) [10]. BMI was calculated as the weight in kilograms (kg) divided by the height in meters squared (m2). Because of the high proportion of missing data on birth weight (44.9 %) and its colinearity with the body shape, the models were adjusted for available body size (thinner, plumper, or about average) and height sizes (shorter, taller, or about average) at age 10 years.

2.5Assessment of metabolic markersBlood samples were collected at recruitment and biochemistry measures were performed and externally validated with stringent quality control in the UK Biobank. The full details on assay performance have been given elsewhere [20]. On the basis of previous studies [21–23], BMI, waist circumference (WC), and circulating biomarkers including serum triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), all known risk factors for liver diseases and previously shown to be associated with tobacco smoking, were selected as possible mediators in the association between early-life tobacco smoke exposure and CLD in adulthood. HbA1c levels were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography with the VARIANT II Turbo analyzer (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Serum TG, LDL-C, HDL-C, ALT, AST, and GGT were measured on a Beckman Coulter AU5800.

2.6Statistical analysisBaseline characteristics of the study participants were described according to in utero tobacco smoke exposure and the age of smoking initiation as number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for CLD incidence in relation to early-life tobacco exposure. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using the Schoenfeld residuals method. Three multivariable models were built. Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age at recruitment. Model 2 was adjusted for model 1 plus ethnicity, birthplace, TDI, drinking status, healthy diet score, physical activity in the analysis of in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and further adjusted for body and height sizes at age 10 years in the analysis of the age of smoking initiation. Model 3 was adjusted for model 2 plus BMI, prevalent diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Model 4 was adjusted for model 3 plus the use of antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents. The linear trend across the age of smoking initiation was tested using the age group as a continuous variable.

When analyzing the joint effects of in utero tobacco exposure and the age of smoking initiation, we categorized the participants into eight groups, and set never-smokers without in utero tobacco exposure as the reference group. To assess the influence of smoking cessation in adulthood, we categorized participants into seven groups based on the age of smoking initiation and smoking status at baseline to investigate their joint effects on CLD incidence, with a reference group of never-smokers. We further examined the combined association of in utero tobacco exposure, age of smoking initiation, and current smoking status with CLD incidence.

The mediation effects of metabolic markers on the association between early-life tobacco exposure and risk of incident CLD in adulthood were evaluated using mediation package in R. Indirect, direct, and total effects for each mediator were computed via combining the mediator-exposure models and the mediator-outcome models with adjustment of all the covariates in Model 3. The mediation proportions were then calculated as the ratio of the natural indirect effect to the total effect. Quasi-Bayesian estimation with 500 iterations was used to compute the 95 % CIs and P values of the proportion of mediation.

Furthermore, we conducted a series of stratified analyses to evaluate potential modification by the following characteristics: age at recruitment (<60 or ≥60), sex (female versus male), TDI (

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. First, we additionally adjusted for use of antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, insulin, and oral antidiabetic agents. Second, missing values for covariates were imputed by multiple imputation with chained equations to test the influence of missing covariates. Third, the primary analyses were repeated after excluding participants who developed CLD within the first 2 years of follow-up to reduce potential reverse causality or excluding participants with prevalent diseases (diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia) at baseline. Fourth, we used a more restrictive definition of NAFLD, excluding other CLD subtypes, to assess potential outcome misclassification. Lastly, proportional subdistribution hazards regression models were used to account for competing risk of death. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and R, version 4.3.1 (R Foundation). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7Ethical considerationsThe UK Biobank received ethics approval from the North West Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee (reference no 11/NW/0382). Written informed consent was obtained for all participants electronically.

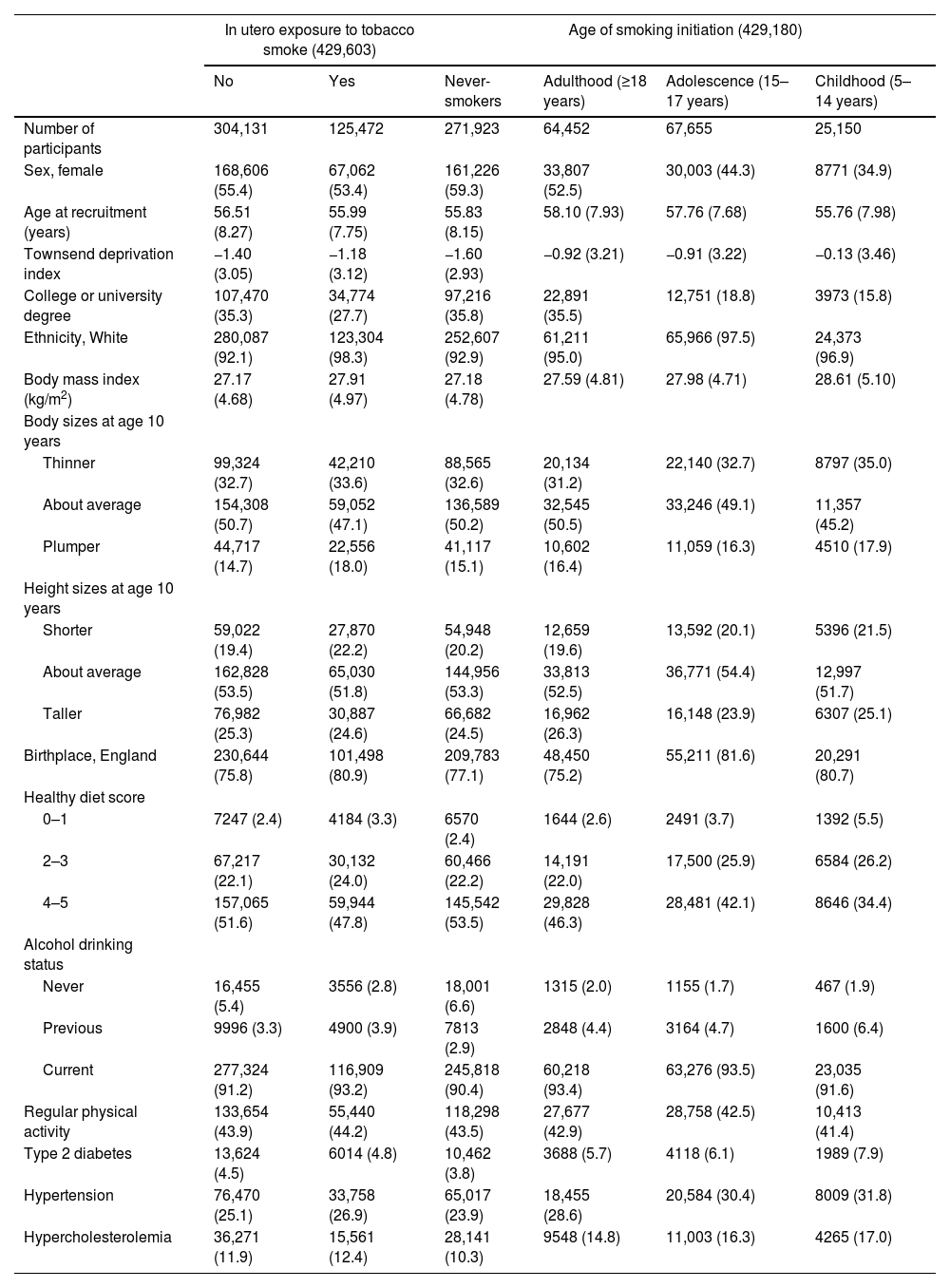

3Results3.1Characteristics of the study populationAmong the analytic participants, 29.2 % reported a history of in utero tobacco exposure, and 15.0 %, 15.8 %, and 5.9 % started smoking in adulthood, adolescence, and childhood, respectively. Table 1 shows the cohort characteristics according to early-life tobacco exposure. Compared to those without in utero tobacco exposure, participants with in utero exposure were slightly younger, less educated, more likely to be males and drinkers, had higher BMI and TDI, and higher prevalence of unhealthy diet and chronic diseases. The results were generally consistent for participants with early initiation of smoking as compared with never-smokers.

Characteristics of study participants according to in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and age of smoking initiation.

Data are mean values (standard deviation) for continuous variables and n ( %) for categorical variables. All P < 0.001 for comparisons across groups.

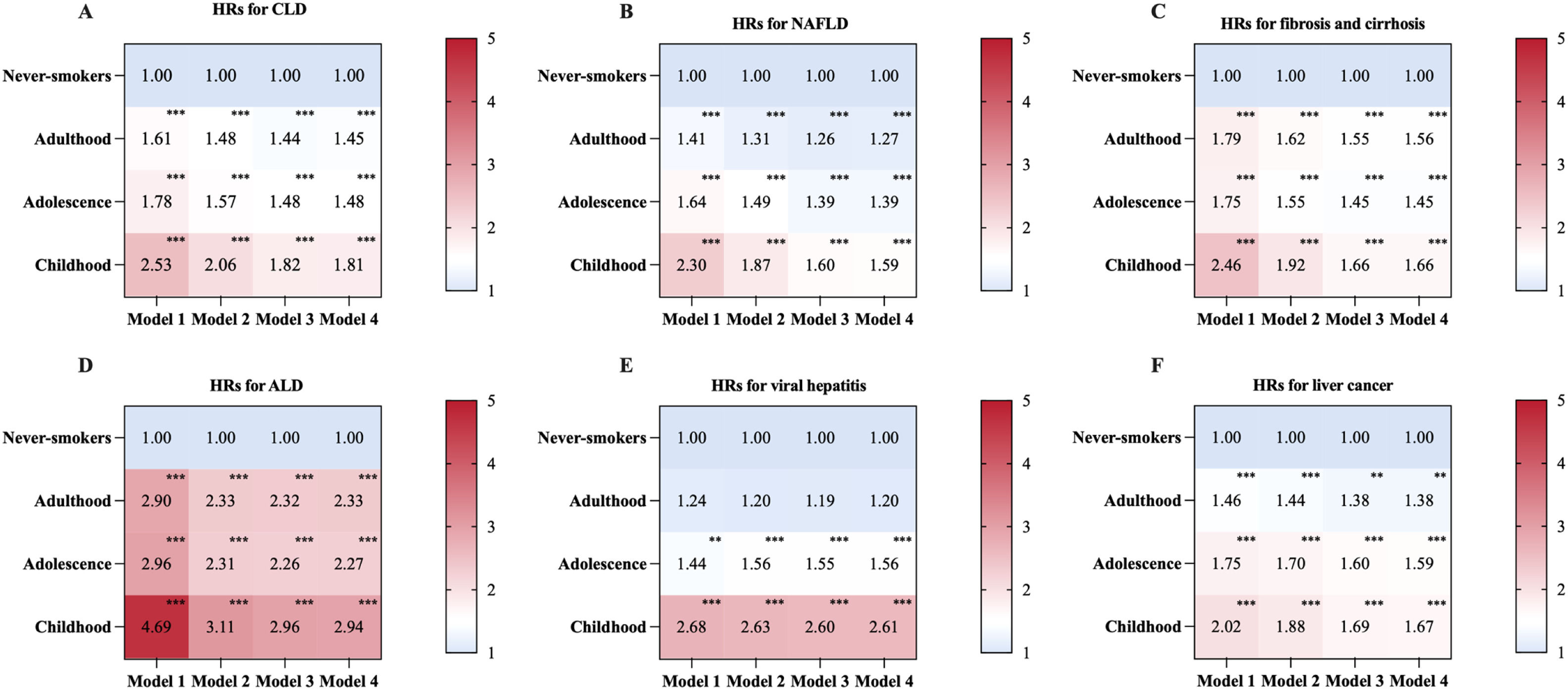

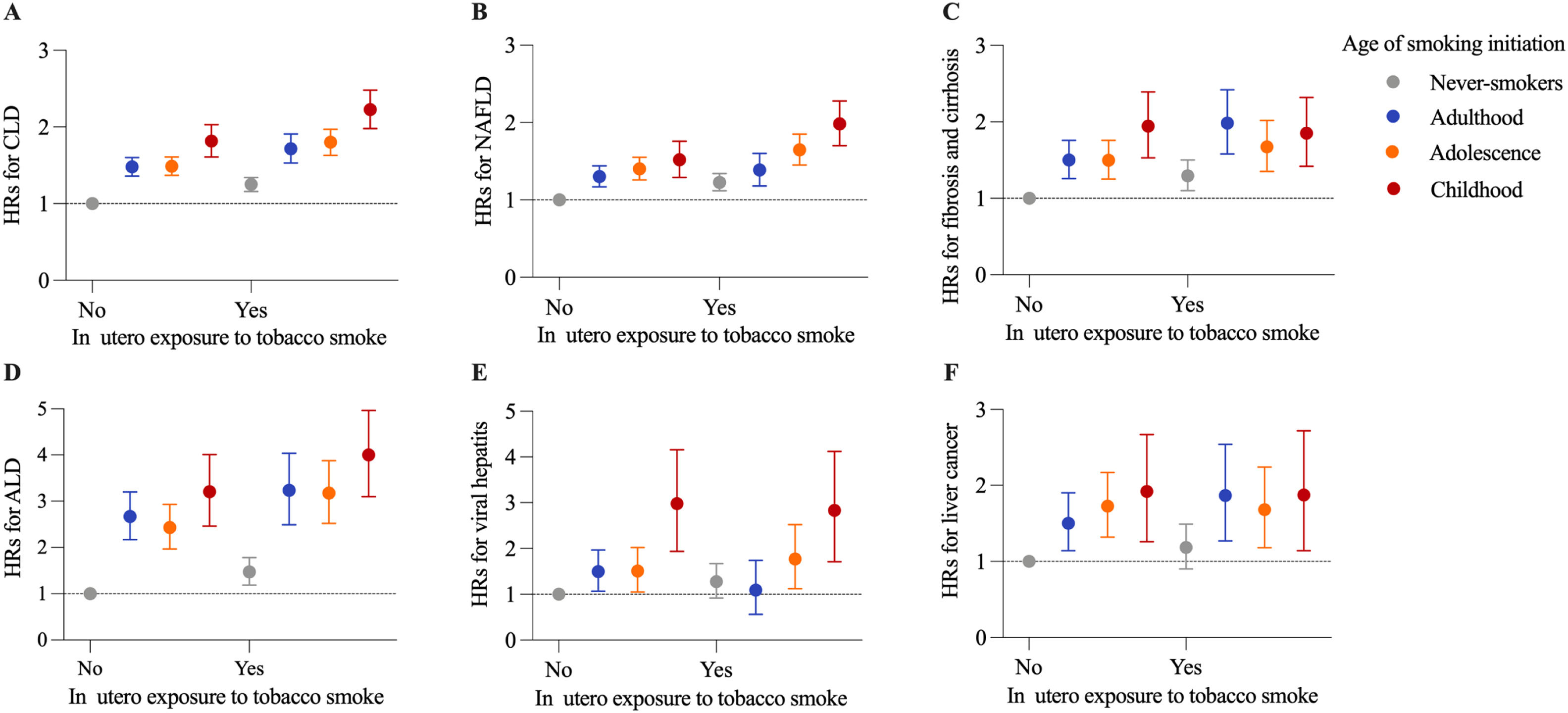

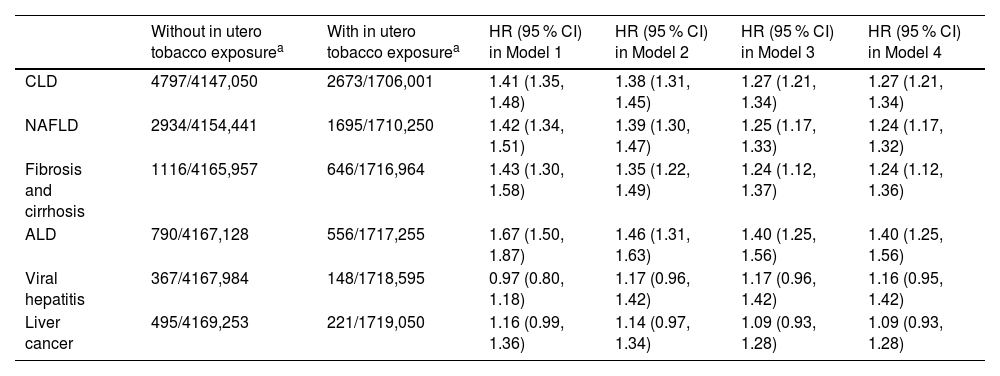

During a median follow-up period of 14.0 (age of smoking initiation dataset: 14.0) years, we documented 7560 (7804) incident CLD cases, including 4629 (4748) NAFLD, 1762 (1855) fibrosis and cirrhosis, 1346 (1397) ALD, 515 (514) viral hepatitis, and 716 (741) liver cancer cases. Compared with participants without in utero tobacco exposure, participants with in utero exposure had an increased risk of CLD (HR, 1.27; 95 % CI: 1.21, 1.34) after adjustment for Model 4 (Table 2). Similar associations were found for individual CLDs with the exception of viral hepatitis and liver cancer. The adjusted HR (95 % CI) associated with in utero tobacco exposure was 1.24 (1.17,1.32) for NAFLD, 1.24 (1.12, 1.36) for fibrosis and cirrhosis, 1.40 (1.25, 1.56) for ALD, 1.16 (0.95, 1.42) for viral hepatitis, and 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) for liver cancer. Among the smokers (current or former), the risk of CLD was highest in those who started smoking in childhood, followed by those who started smoking in adolescence and adulthood (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). In comparison with never-smokers, the HRs (95 % CIs) of CLD incidence for smoking initiation in adulthood, adolescence, and childhood were 1.45 (1.36, 1.54), 1.48 (1.40, 1.57), and 1.81 (1.68, 1.96), respectively (P trend <0.001). The greatest risks of individual CLDs were also observed among smokers who started smoking in childhood, with an HR ranging from 1.59 to 2.94. Restricted cubic splines demonstrated a linear association between younger age of smoking initiation below age 18 and higher CLD risk (Supplementary Figure 2). When analyzing the joint effects of in utero tobacco exposure and the age of smoking initiation, participants who experienced in utero exposure and initiated smoking in childhood had the highest risk of overall CLD incidence (HR, 2.22; 95 % CI: 1.98, 2.48), as well as NAFLD (1.97; 1.70, 2.28) and ALD (3.93; 3.10, 4.97) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figure 3).

Associations of in utero exposure to tobacco smoke with incidence of CLD and CLD subtypes.

| Without in utero tobacco exposurea | With in utero tobacco exposurea | HR (95 % CI) in Model 1 | HR (95 % CI) in Model 2 | HR (95 % CI) in Model 3 | HR (95 % CI) in Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLD | 4797/4147,050 | 2673/1706,001 | 1.41 (1.35, 1.48) | 1.38 (1.31, 1.45) | 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) | 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) |

| NAFLD | 2934/4154,441 | 1695/1710,250 | 1.42 (1.34, 1.51) | 1.39 (1.30, 1.47) | 1.25 (1.17, 1.33) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.32) |

| Fibrosis and cirrhosis | 1116/4165,957 | 646/1716,964 | 1.43 (1.30, 1.58) | 1.35 (1.22, 1.49) | 1.24 (1.12, 1.37) | 1.24 (1.12, 1.36) |

| ALD | 790/4167,128 | 556/1717,255 | 1.67 (1.50, 1.87) | 1.46 (1.31, 1.63) | 1.40 (1.25, 1.56) | 1.40 (1.25, 1.56) |

| Viral hepatitis | 367/4167,984 | 148/1718,595 | 0.97 (0.80, 1.18) | 1.17 (0.96, 1.42) | 1.17 (0.96, 1.42) | 1.16 (0.95, 1.42) |

| Liver cancer | 495/4169,253 | 221/1719,050 | 1.16 (0.99, 1.36) | 1.14 (0.97, 1.34) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) |

Data are cases/person-years.

Abbreviations: ALD, alcoholic liver disease; CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease; HR, hazard ratio; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Model 1 was adjusted for age at recruitment and sex.

Model 2 was additionally adjusted for ethnicity, birthplace, Townsend deprivation index, drinking status, diet score, and physical activity based on model 1.

Model 3 was additionally adjusted for BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia based on model 2.

Model 4 was additionally adjusted for the use of antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents based on model 3.

Associations of age of smoking initiation with incidence of CLD and CLD subtypes. The heat maps show the HRs for overall CLD (A), NAFLD (B), fibrosis and cirrhosis (C), ALD (D), viral hepatitis (E), and liver cancer (F) incidence in relation to age of smoking initiation. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for body and height sizes at age 10 years, ethnicity, birthplace, Townsend deprivation index, drinking status, diet score, and physical activity based on model 1. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia based on model 2. Model 4 was additionally adjusted for the use of antihypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents based on model 3. ALD, alcoholic liver disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; HR, hazard ratio; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

The joint effects of in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and age of smoking initiation on incidence of CLD and CLD subtypes. The HRs (95 % CIs) of overall CLD (A), NAFLD (B), fibrosis and cirrhosis (C), ALD (D), viral hepatitis (E), and liver cancer (F) incidence associated with joint categories of in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and the age of smoking initiation. All models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, birthplace, Townsend deprivation index, body and height sizes at age 10 years, drinking status, diet score, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. ALD, alcoholic liver disease; CLD, chronic liver disease; HR, hazard ratio; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

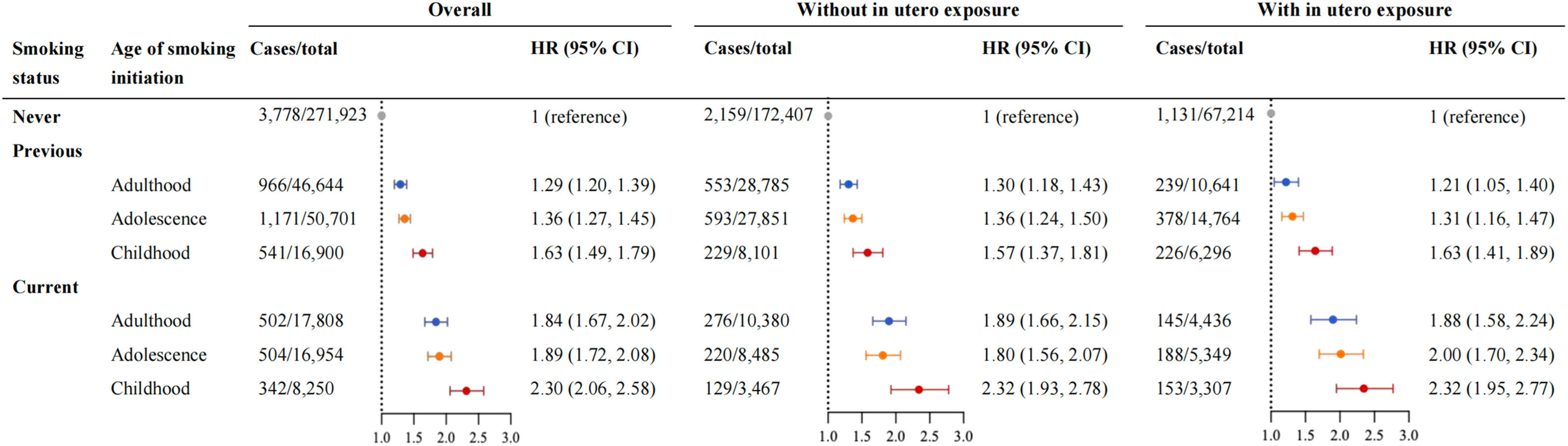

To evaluate the influence of smoking cessation on the CLD risk associated with early-life tobacco exposure, we further examined the combined association of current smoking status and the age of smoking initiation with CLD incidence (Fig. 3). Compared with never-smokers, the HR (95 % CI) for CLD incidence was 2.30 (2.06, 2.58) and 1.63 (1.49, 1.79) for current and former smokers who initiated smoking in childhood, and 1.89 (1.72, 2.08) and 1.36 (1.27, 1.45) for those who initiated smoking in adolescence, respectively. The results were broadly comparable between participants with and without in utero exposure to tobacco smoke. When considered jointly, the HR (95 % CI) of current smokers' CLD incidence with smoking initiation in childhood and in utero tobacco exposure was 2.79 (2.36, 3.30) (Supplementary Figure 4).

The joint effects of current smoking status and age of smoking initiation on CLD incidence. The HRs (95 % CIs) of CLD incidence according to joint categories of current smoking status and the age of smoking initiation among overall population and stratified by in utero exposure to tobacco smoke. All models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, birthplace, Townsend deprivation index, body and height sizes at age 10 years, drinking status, diet score, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease; HR, hazard ratio.

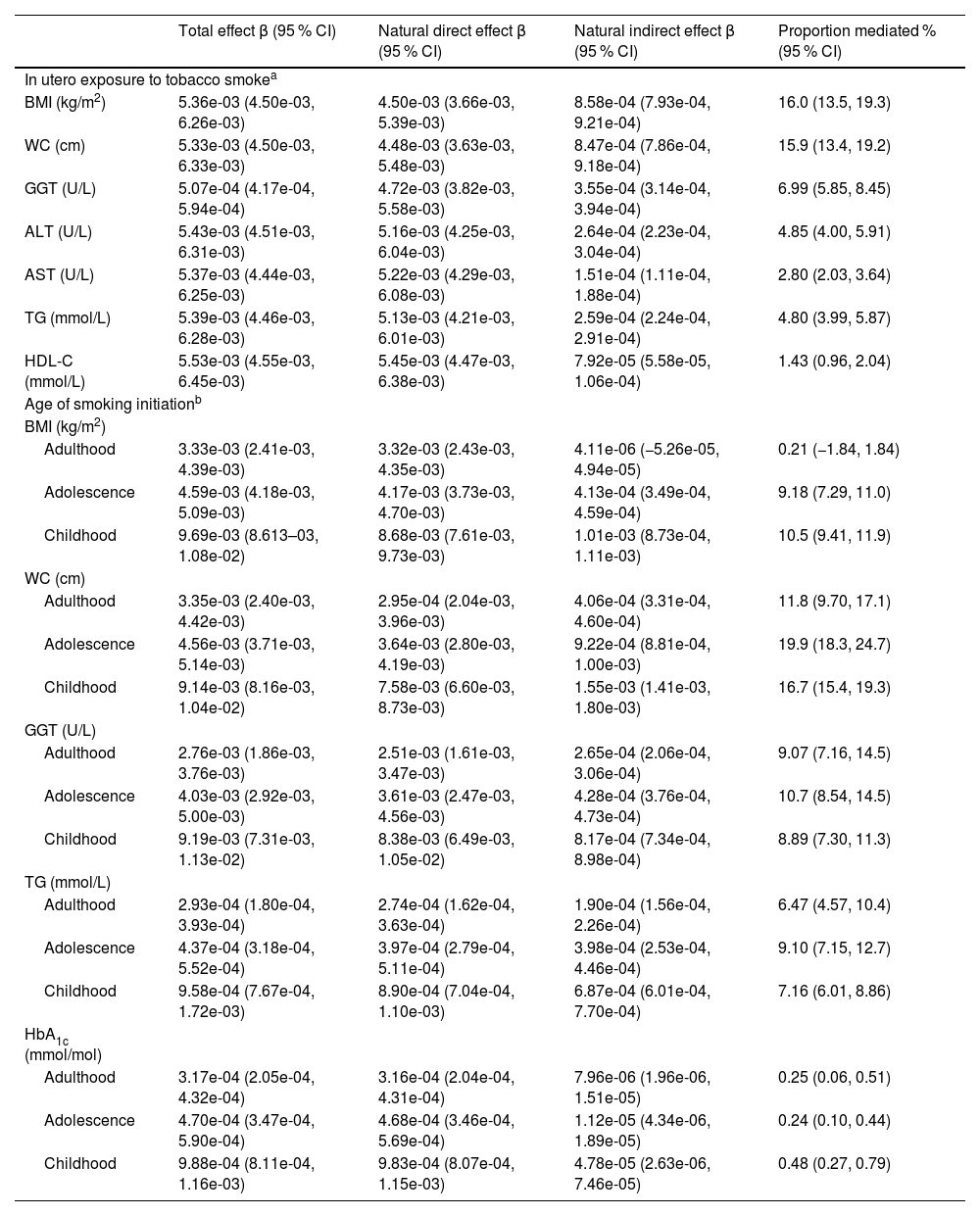

All selected markers were associated with early-life exposure to tobacco smoke and risk of incident CLD (Supplementary Table 3). Among the markers, BMI, WC, TG, HDL-C, ALT, AST, and GGT were identified as significant mediators in the associations of in utero tobacco exposure with CLD incidence, and the largest proportions of mediation effects were found for BMI (16.0 %) and WC (15.9 %) (Table 3). The association between the age of smoking initiation and CLD was mediated by BMI, WC, TG, HbA1c, and GGT, with WC being the strongest mediator, accounting for 16.7 % of the association with smoking initiation in childhood and 19.9 % of the association with smoking initiation in adolescence.

Mediators linking the associations of in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and age of smoking initiation with CLD incidence.

| Total effect β (95 % CI) | Natural direct effect β (95 % CI) | Natural indirect effect β (95 % CI) | Proportion mediated % (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In utero exposure to tobacco smokea | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 5.36e-03 (4.50e-03, 6.26e-03) | 4.50e-03 (3.66e-03, 5.39e-03) | 8.58e-04 (7.93e-04, 9.21e-04) | 16.0 (13.5, 19.3) |

| WC (cm) | 5.33e-03 (4.50e-03, 6.33e-03) | 4.48e-03 (3.63e-03, 5.48e-03) | 8.47e-04 (7.86e-04, 9.18e-04) | 15.9 (13.4, 19.2) |

| GGT (U/L) | 5.07e-04 (4.17e-04, 5.94e-04) | 4.72e-03 (3.82e-03, 5.58e-03) | 3.55e-04 (3.14e-04, 3.94e-04) | 6.99 (5.85, 8.45) |

| ALT (U/L) | 5.43e-03 (4.51e-03, 6.31e-03) | 5.16e-03 (4.25e-03, 6.04e-03) | 2.64e-04 (2.23e-04, 3.04e-04) | 4.85 (4.00, 5.91) |

| AST (U/L) | 5.37e-03 (4.44e-03, 6.25e-03) | 5.22e-03 (4.29e-03, 6.08e-03) | 1.51e-04 (1.11e-04, 1.88e-04) | 2.80 (2.03, 3.64) |

| TG (mmol/L) | 5.39e-03 (4.46e-03, 6.28e-03) | 5.13e-03 (4.21e-03, 6.01e-03) | 2.59e-04 (2.24e-04, 2.91e-04) | 4.80 (3.99, 5.87) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 5.53e-03 (4.55e-03, 6.45e-03) | 5.45e-03 (4.47e-03, 6.38e-03) | 7.92e-05 (5.58e-05, 1.06e-04) | 1.43 (0.96, 2.04) |

| Age of smoking initiationb | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Adulthood | 3.33e-03 (2.41e-03, 4.39e-03) | 3.32e-03 (2.43e-03, 4.35e-03) | 4.11e-06 (−5.26e-05, 4.94e-05) | 0.21 (−1.84, 1.84) |

| Adolescence | 4.59e-03 (4.18e-03, 5.09e-03) | 4.17e-03 (3.73e-03, 4.70e-03) | 4.13e-04 (3.49e-04, 4.59e-04) | 9.18 (7.29, 11.0) |

| Childhood | 9.69e-03 (8.613–03, 1.08e-02) | 8.68e-03 (7.61e-03, 9.73e-03) | 1.01e-03 (8.73e-04, 1.11e-03) | 10.5 (9.41, 11.9) |

| WC (cm) | ||||

| Adulthood | 3.35e-03 (2.40e-03, 4.42e-03) | 2.95e-04 (2.04e-03, 3.96e-03) | 4.06e-04 (3.31e-04, 4.60e-04) | 11.8 (9.70, 17.1) |

| Adolescence | 4.56e-03 (3.71e-03, 5.14e-03) | 3.64e-03 (2.80e-03, 4.19e-03) | 9.22e-04 (8.81e-04, 1.00e-03) | 19.9 (18.3, 24.7) |

| Childhood | 9.14e-03 (8.16e-03, 1.04e-02) | 7.58e-03 (6.60e-03, 8.73e-03) | 1.55e-03 (1.41e-03, 1.80e-03) | 16.7 (15.4, 19.3) |

| GGT (U/L) | ||||

| Adulthood | 2.76e-03 (1.86e-03, 3.76e-03) | 2.51e-03 (1.61e-03, 3.47e-03) | 2.65e-04 (2.06e-04, 3.06e-04) | 9.07 (7.16, 14.5) |

| Adolescence | 4.03e-03 (2.92e-03, 5.00e-03) | 3.61e-03 (2.47e-03, 4.56e-03) | 4.28e-04 (3.76e-04, 4.73e-04) | 10.7 (8.54, 14.5) |

| Childhood | 9.19e-03 (7.31e-03, 1.13e-02) | 8.38e-03 (6.49e-03, 1.05e-02) | 8.17e-04 (7.34e-04, 8.98e-04) | 8.89 (7.30, 11.3) |

| TG (mmol/L) | ||||

| Adulthood | 2.93e-04 (1.80e-04, 3.93e-04) | 2.74e-04 (1.62e-04, 3.63e-04) | 1.90e-04 (1.56e-04, 2.26e-04) | 6.47 (4.57, 10.4) |

| Adolescence | 4.37e-04 (3.18e-04, 5.52e-04) | 3.97e-04 (2.79e-04, 5.11e-04) | 3.98e-04 (2.53e-04, 4.46e-04) | 9.10 (7.15, 12.7) |

| Childhood | 9.58e-04 (7.67e-04, 1.72e-03) | 8.90e-04 (7.04e-04, 1.10e-03) | 6.87e-04 (6.01e-04, 7.70e-04) | 7.16 (6.01, 8.86) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | ||||

| Adulthood | 3.17e-04 (2.05e-04, 4.32e-04) | 3.16e-04 (2.04e-04, 4.31e-04) | 7.96e-06 (1.96e-06, 1.51e-05) | 0.25 (0.06, 0.51) |

| Adolescence | 4.70e-04 (3.47e-04, 5.90e-04) | 4.68e-04 (3.46e-04, 5.69e-04) | 1.12e-05 (4.34e-06, 1.89e-05) | 0.24 (0.10, 0.44) |

| Childhood | 9.88e-04 (8.11e-04, 1.16e-03) | 9.83e-04 (8.07e-04, 1.15e-03) | 4.78e-05 (2.63e-06, 7.46e-05) | 0.48 (0.27, 0.79) |

Abbreviations: ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease; GGT, Gamma glutamyltransferase; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin A1c; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; WC, waist circumference.

In sensitivity analyses, when we excluded incident cases during the first 2 years of follow-up or those with prevalent chronic diseases at baseline, imputed missing values for covariates, or considered the competing risk of death, the associations between early-life tobacco exposure and incident CLD remained unchanged (Supplementary Tables 4–7).

We performed a series of stratified analyses according to characteristics (Supplementary Tables 8–9). Significant modification effects of age and body and height sizes at 10 years on the association between in utero exposure to tobacco smoke and CLD were found (all P interaction <0.05). For example, the HR estimates were greater in younger participants (<60 years) with in utero tobacco exposure than in older participants. There was also a stronger association in participants who were thinner or shorter at age 10 years than in those with other body or height sizes. Besides, we observed significant interactions between the age of smoking initiation and body size at 10 years and adult BMI on CLD incidence (all P interaction <0.05).

4DiscussionIn this large cohort study, tobacco exposure in early-life stages, including the fetal periods, childhood, and adolescence, was significantly associated with an increased risk of CLD in adulthood. Participants with both in utero exposure and smoking initiation in childhood had the highest CLD risk. Furthermore, BMI, WC, serum lipids, HbA1c, and liver enzyme levels partially mediated the associations between early-life tobacco exposure and incident CLD. These findings not only revealed a risk pattern overlooked by previous studies confined to adult smoking or a narrow focus on NAFLD, but also confirmed the long-term health effects of early-life exposure and extended the findings to CLD incidence.

Accumulative evidence indicates that early-life adverse exposure might have a profound and lasting impact on disease susceptibility in adulthood [7,24,25]. Cigarette smoking, a major environmental risk factor for premature morbidity and mortality, has been linked with onset and progression of liver diseases [26], but how its occurrence in a critical developmental window may affect the incidence of CLD later in life remains unclear. In our study, we found that intrauterine tobacco exposure and smoking initiation in childhood and adolescence were pronouncedly associated with higher risks of CLD as well as major subtypes including NAFLD, ALD, cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, and liver cancer in adulthood. The CLD risk increased as the age of smoking initiation decreased. Similar to our results, a prospective cohort study of 1315 participants from the Young Finns Study found a positive association between childhood passive smoking and increased risk of adult NAFLD [27], even though the results might not be directly comparable to our estimates derived from active smoking. In addition, we detected a joint effect of in utero tobacco exposure and smoking in childhood/adolescence on increased CLD incidence. Our findings demonstrate the crucial role of early-life tobacco exposure in the development of CLD, highlighting the importance of reducing early-life tobacco exposure to prevent liver diseases later in life.

The association between early-life tobacco exposure and CLD is biologically plausible, involving different pathophysiological pathways including oxidative stress, inflammation, and oncogenic signals [26]. Maternal smoking during pregnancy could indirectly cause exposure to tobacco smoke in utero, which may interfere with liver development by altering hypoxemia and the structure and function of the placenta [28,29]. Meanwhile, toxins contained in tobacco smoke, such as nicotine, carbon monoxide, heavy metals, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, could cross the placental barrier and induce generation of reactive oxygen species, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, leading to permanent metabolism alterations, thereby enhancing susceptibility to CLD in adulthood [30,31]. Furthermore, it has been shown that telomere shortening, a biomarker of cellular aging that is related to tobacco exposure in early life [10,32], increases the risk of multiple liver diseases [33]. In addition to direct liver damage due to tobacco smoke during childhood and adolescence, starting smoking at a younger age may predispose individuals to a longer trajectory of tobacco use and heavier consumption, ultimately raising the risk of CLD in their lives [34,35]. Furthermore, cigarette smoking tends to be frequently accompanied by other unhealthy behavioral factors (e.g., alcohol consumption), which could interact synergistically to affect liver-related outcomes.

From public health perspective, elucidating how smoking cessation influences disease risk conferred by early-life tobacco exposure is of great significance. We hereby analyzed the joint association of current smoking status and early-life exposure to tobacco smoke with liver diseases and found that individuals with persistent exposure to smoking across childhood and adulthood had the highest risk of CLD, whereas this risk was remarkably lower among those who initiated smoking in childhood but quit later. Consistently, in the Young Finns Study, individuals with passive smoking throughout childhood and adulthood period had 2 times higher risk of NAFLD than those without passive smoking in either childhood or adulthood [27]. According to data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service, earlier smoking cessation was associated with greater cancer risk reduction including liver cancer [36]. Of note, compared with never-smokers in this study, individuals who were exposed to tobacco early in life but quit later still showed an elevated risk of CLD. These findings suggest that prevention of smoking should start as early as possible and maintain throughout lifetime to reduce CLD incidence.

In mediation analyses, we found that the association between early-life tobacco exposure and CLD incidence was partially mediated by obesity-related traits, glycemic status, liver function, and lipid profile, with the largest mediation effect found for BMI and WC. Mendelian randomization analyses have identified causal relationships of smoking initiation with higher BMI and WC in adulthood [37], which might be related to smoking-induced dysregulation of adipose tissue-derived endocrine hormones [38]. Moreover, serum lipids have been suggested to play roles in the association between smoking and incident NAFLD in both human and animal studies [39,40]. Elevated levels of HbA1c are associated with smoking [41], and may contribute to liver steatosis and fibrosis either directly by stimulating receptor for advanced glycation end products or indirectly by promoting hypoxia and suppressing NO release [42]. Furthermore, liver enzymes including GGT, ALT and AST are well-established predictors of liver injury caused by various exogenous chemicals such as tobacco substances [43]. These metabolic traits may represent functional intermediates ranging from early epigenetic reprogramming to adult liver diseases.

Our study adds to the current epidemiological evidence by demonstrating for the first time that in utero and childhood/adolescence tobacco exposure was associated with increased CLD risk in adulthood. Besides, the identification of mediating markers offers valuable insights into the potential mechanism underlying the link between early-life tobacco exposure and CLD incidence. The strength of our study included comprehensive analysis of liver diseases in a large-scale cohort with long follow-up, temporality from early-life tobacco exposure to adult outcome, and consideration of various potential confounders and mediators. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, more detailed tobacco exposure information on the duration and pack-years of smoking, second-hand smoke, and environmental tobacco was not assessed due to the lack of data in the UK Biobank, which limits our ability to perform more in-depth analyses such as assessing the dose-response relationship. Second, information on early-life tobacco exposure was retrospectively collected through self-reported questionnaires, rendering the data prone to recall bias. The offspring’s report of in utero tobacco exposure has been depicted to be a good proxy measure for the mother’s own report [44]. It is expected that the misclassification of exposure is likely to be non-differential between groups and would attenuate the association toward null findings. Third, medical conditions were obtained from hospital inpatient records and cancer registry, where there was possibility of missed diagnoses of CLD (e.g., non-severe NAFLD) from primary care or outpatient clinic. Fourth, residual and unmeasured confounding by early-life factors such as parental socioeconomic status, maternal weight change, and lifestyle habits during pregnancy may exist. However, the results were robust when we adjusted for adult covariates and potential mediators. Fifth, the UK Biobank participants were mostly White British and were generally healthier with higher socioeconomic status compared with the whole UK population, thus the generalizability of our results to other populations should be cautiously interpreted. Lastly, due to the observational nature of the study, causal associations cannot be inferred.

5ConclusionsIn summary, leveraging data from a large prospective cohort, we found that exposure to tobacco smoke in the fetal period, childhood, and adolescence was associated with an increased risk of CLD in adulthood, while subsequent smoking cessation substantially reduced the risk. Moreover, obesity-related traits, glycemic status, liver function, and lipid profile significantly mediated the association between early-life tobacco exposure and CLD incidence. Our findings highlight the importance of reducing tobacco exposure from the prenatal period throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood to prevent liver diseases. Further studies are warranted to confirm our findings and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Author contributionsBin Wang and Yingli Lu had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Bin Wang, Xiaoqin Xu. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Xiaoqin Xu, Jiang Li, Bin Wang. Critical revision of the manuscript: Bin Wang, Yingli Lu. Statistical analysis: Xiaoqin Xu, Jiang Li. Administrative, technical, or material support: Xiao Tan, Ningjian Wang. Supervision: Bin Wang, Yingli Lu.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors thank the participants and staff of the UK Biobank for their dedication and contribution to the research. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82404337, 82170870 and 82120108008), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (24ZR1443400 and 22015810500), Major Science and Technology Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2019-01-07-00-01-E00059), and Biobank Project (YBKB202218).