Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) was formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). In 2020, an expert panel from 22 countries recommended renaming NAFLD to MAFLD, abandoning the exclusionary nature of the term “non-alcoholic” and instead adopting inclusion criteria based on metabolic abnormalities to more accurately reflect the nature of the disease [1]. In 2023, the term MASLD was proposed by three major hepatology associations, which not only removed the stigma from the term “fatty” but also differed from MAFLD in diagnostic criteria (e.g., a definite diagnosis can be made in lean patients as long as metabolic abnormality occurs in one indicator); meanwhile, new subtypes such as MetALD were introduced, making the disease definition more scientific, inclusive, and clinically practical [2]. MASLD is a metabolic stress-related chronic liver disease triggered by overnutrition and insulin resistance (IR) in genetically susceptible individuals [3]. MASLD can develop into metabolic-associated steatohepatitis and even lead to end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death. Moreover, MASLD is not only a major cause of increasing global morbidity and mortality of liver-related diseases but also a leading risk factor for metabolic and cardiovascular disorders [1]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that with heavy drinking excluded, 6.3%-45 % (median 25.2%, 95% CI 22.1%-28.7%) of ordinary adults are diagnosed with MASLD by imaging [4]. Nowadays, MASLD has become the most prevalent liver disease with an annually increasing incidence, and it affects one billion people worldwide, placing a heavy burden on individuals, families, and healthcare systems [5,6].

Liver biopsy or imaging is currently the main means of diagnosing MASLD, but the former is invasive and the latter is costly and difficult to popularize. Therefore, it has been a research hotspot to develop efficient and economical noninvasive indicators for diagnosis. Triglyceride-glucose body mass index (TyG-BMI, TyG=ln[triglyceride (mg/dL) × fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL)/2], BMI = kg/m2) is a composite indicator for both glucolipid metabolic disorders and obesity, and its close link to MASLD progression has been documented.

However, great heterogeneity is present in the diagnostic efficacy of TyG-BMI. One study revealed its good diagnostic efficacy on MASLD (AUC 0.956, 95% CI 0.933–0.980) [7], whereas a weak correlation with MASLD has also been found (AUC 0.675, 95% CI 0.598–0.752) [8]. Such a discrepancy may stem from differences in demographics and thresholds. Therefore, we conducted this study using global epidemiological data to fully assess the accuracy of TyG-BMI for MASLD diagnosis, and also performed country-, sex-, and comorbidity-stratified analyses. The findings are expected to offer evidence-based recommendations for clinical use and threshold optimization of TyG-BMI.

2MethodsThis study adhered to the PRISMA guidelines [9] and the protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251023723).

2.1Search strategyWe conducted a systematic search in Embase, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science up to Jul 23, 2025. Keywords (“non-alcoholic fatty liver disease”, “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease”, “metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease”, and “triglyceride-glucose index”) and specific terms (MeSH and Emtree) were combined with Boolean operators (AND/OR/NOT), and the search was optimized with truncation (*). The search strategy is detailed in Table S1.

2.2Eligibility criteriaInclusion criteria: 1) Participants: patients diagnosed with MASLD; 2) Comparison: non-MASLD patients; 3) Outcome: TyG-BMI, with SMD (95% CI), odds ratio (OR) (95 % CI), sensitivity/specificity or AUC (95% CI) reported; 4) Study design: observational studies including cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies.

Exclusion criteria: 1) reviews, conference abstracts, meta-analyses, and case reports; 2) animal experiments; 3) non-English-language studies; 4) inappropriate study types, disease types, study objectives, or interventions; 5) studies with unavailable full text or missing key data.

2.3Study screeningTwo reviewers (A and B) were independently responsible for study screening. First, the retrieved studies were initially screened using EndNote X9 based on pre-established eligibility criteria. Then potentially eligible studies were obtained by reading the title and abstract. Finally, the full text was examined to include eligible studies. Any discrepancy was settled by collective discussion and arbitration by a third senior reviewer (C).

2.4Data extractionTwo reviewers (A and B) independently extracted and cross-checked the following data: 1) basic information (year of publication, first author, and country); 2) participant characteristics (mean age, sex distribution, and comorbid diabetes); 3) methodologic characteristics (gold standard for diagnosis, and TyG-BMI cutoff); 4) outcome metrics (OR and 95% CI, mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, AUC and 95% CI, diagnostic sensitivity/specificity). Any discrepancy was settled by collective discussion and arbitration by a third reviewer (C).

2.5Quality assessmentQuality assessment was conducted independently by two reviewers (A and B) using Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS)-2 from four domains: 1) patient selection (representativeness of participants), 2) index test (measurement method for TyG-BMI), 3) reference standard (diagnostic method for MASLD), and 4) flow and timing (chronological order of tests). The quality scores were independently given and recorded, and any discrepancy was settled by a collective discussion with a third senior reviewer (C).

2.6Statistical analysisStata18.0 and Meta-Disc1.4 were utilized. Pooled effect sizes (OR/SMD and 95% CI) and diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, SROC curve, diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), and likelihood ratios (LRs) were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed by the I² statistic; a random- or fixed-effects model was applied if I² > 50% (great heterogeneity) or I²≤50%, respectively. To further investigate the source of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses by country, sex, sample size, comorbid diabetes, gold standard for diagnosis, and cutoff. The findings were assessed for robustness by leave-one-out sensitivity analyses, and publication bias was examined by Egger's test, Deeks' test, and funnel plot. All tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 suggested statistical significance.

2.7Ethical statementsThis systematic review and meta-analysis utilized aggregated data from previously published studies. All original studies included in this analysis were conducted under ethical oversight, with appropriate institutional review board approvals obtained by the primary investigators in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. As this work constitutes secondary analysis of existing literature, no new ethical approval was required. Informed consent procedures were the responsibility of the original study investigators, as this meta-analysis did not involve direct collection or processing of individual patient data. The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript. This study was conducted in compliance with PRISMA guidelines, and its protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251023723).

3Results3.1Search resultsWe initially retrieved 6254 relevant studies (n = 270 in PubMed, 465 in Embase, 4928 in Web of Science, and 591 in Cochrane Library), from which 672 were identified as duplicates. After reading the title and abstract, 5526 were excluded. The full text of the remainder was examined, and we excluded 25 studies (n = 5 due to incomplete data, n = 12 due to inappropriate study design, n = 3 due to unavailable full text, and n = 5 as duplicate publications). Finally, 31 studies were included (Fig. 1).

3.2Baseline characteristicsWe included 31 studies [7,8,10–38], involving 498,528 patients aged 21–77 years. The included studies were mainly from Asia (18 in China [7,10,11,16–19,22,23,26–29,32,35–38]; 3 in Japan [12,13,30]; 2 in Korea [15,24]), followed by North America (4 in the USA: [14,20,21,34]), Middle East (2 in Iran [8,33]), Latin America (1 in Mexico [34]), and Africa (1 in South Africa [25]). The sample size was <1000 in 11 studies [7,8,10,11,20,22,23,25,31,33,34], 1000–10,000 in 11 studies [14,18,19,21,26,28,29,32,35–37], and >10,000 in 9 studies [12,13,15–17,24,27,30,38]. Patients with comorbid diabetes were included in 5 studies [10,11,19,22,23], while the influence of diabetes was excluded in the remaining 26 studies [7,8,12–18,20,21,24–38]. As for the gold standard for MASLD diagnosis, ultrasound was adopted in 21 studies [7,10–13,15–19,23–30,35,36,38] and controlled attenuation parameters (CAP) in 10 studies [8,14,20–22,31–34,37] (Table S2).

3.3Quality assessmentWe found by the QUADAS-2 that 25% of the studies had a high risk of bias in the domain of the index test, while they had a low risk in other domains (Fig. 2).

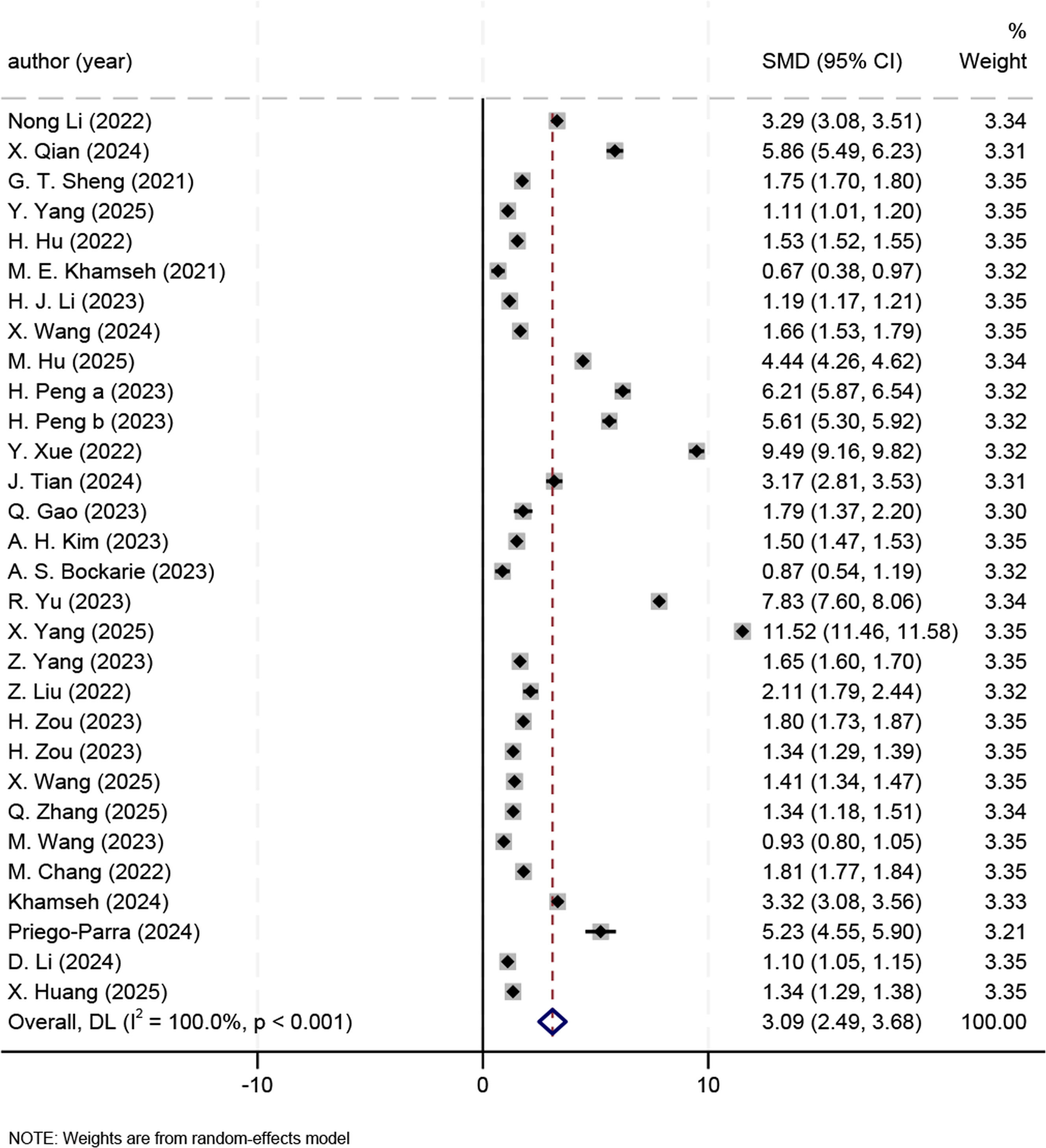

3.4Meta analysis results3.4.1Effect sizeWe found that the overall effect size was significant (SMD 3.09, 95% CI 2.49–3.68, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Due to great heterogeneity (I² = 100.0%, P < 0.001), we adopted a random-effects model and further conducted subgroup analyses.

Compared with non-MASLD patients, MASLD patients had elevated TyG-BMI across countries: China (SMD 4.96, 95% CI 4.04–5.88), the USA (SMD 4.17, 95% CI 2.64–5.71), Mexico (SMD 5.23, 95% CI 4.55–5.90), Japan (SMD 1.58, 95% CI 1.24–1.92), Korean (SMD 1.50, 95% CI 1.47–1.53), Iran (SMD 2.00, 95% CI -0.60–4.59), and South Africa (SMD 0.87, 95% CI 0.54–1.19). The subgroup analyses revealed that the country was not a source of heterogeneity.

Compared with non-MASLD patients, MASLD patients had elevated TyG-BMI across sample sizes: n < 1000 (SMD 3.28, 95% CI 2.22–4.34), n = 1000–10,000 (SMD 5.69, 95% CI 4.79–6.59), and n > 10,000 (SMD 2.96, 95% CI 1.59–4.32). The SMD of the effect size was 3.71 (95% CI 2.66–4.77) for studies reporting comorbid diabetes and 4.23 (95% CI 3.57–4.90) for non-diabetic ones. For studies using ultrasound and CAP, the SMD of the effect size was 2.79 (95% CI 2.06–3.51) and 6.73 (95 % CI 4.29–9.16), respectively. Besides, the SMD of the effect size was 3.81 (95% CI 2.57–5.06), 5.20 (95% CI 4.62–5.79), 3.48 (95% CI 0.55–6.41), and 1.16 (95% CI 0.95–1.38) for studies with a TyG-BMI cutoff of <100, >200, 100–200, and not reported (NR), respectively (Table S3).

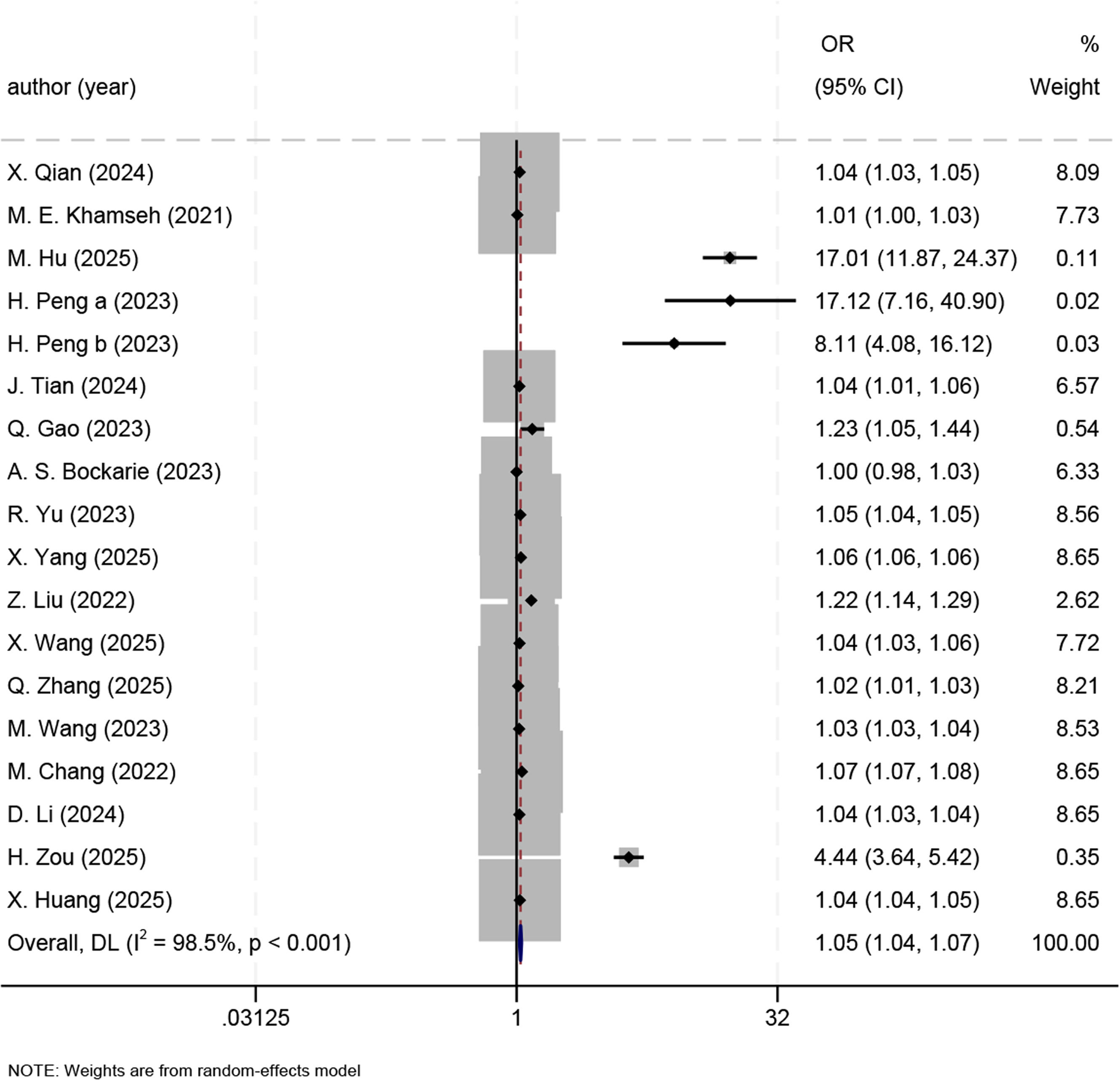

3.4.2ORsWe meta-analyzed the ORs of the association of TyG-BMI with the MASLD risk in 19 studies [7,8,11–13,19,20,22,23,25–27,30–32,35–38]. For each one-unit increase in TyG-BMI, the MASLD risk rose by 5% (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.04–1.07, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Due to great heterogeneity (I² = 98.5%, P < 0.001), we adopted a random-effects model and conducted subgroup analyses.

In China, the MASLD risk rose by 7 % for each one-unit increase in TyG-BMI (OR 1.07, 95 % CI 1.05–1.08); (OR 2.25, 95% CI 0.92–5.47) in Japan, (OR 1.01, 95 % CI 1.00–1.02) in Iran, (OR 5.04, 95% CI 0.74–34.34) in the USA, (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.98–1.03) in South Africa; it can be seen that country was not a source of heterogeneity. In addition, the sample size was not a source of heterogeneity: >10,000 (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.36–1.48), <1000 (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.09), and 1000–10,000 (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.04–1.09). Heterogeneity was not caused by comorbid diabetes: comorbid diabetes (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.29–1.76), and no diabetes (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.12–1.16), or by the gold standard for diagnosis: ultrasound (OR 1.16, 95 % CI 1.14–1.18), and CAP (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.07–1.19). The TyG-BMI cutoff was not associated with heterogeneity: <100 (OR 4.18, 95% CI 0.27–64.71), 100–200 (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.30–1.40), >200 (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.05–1.10), and NR (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.03). To sum up, no source of heterogeneity was identified by the subgroup analyses of ORs (Table S4).

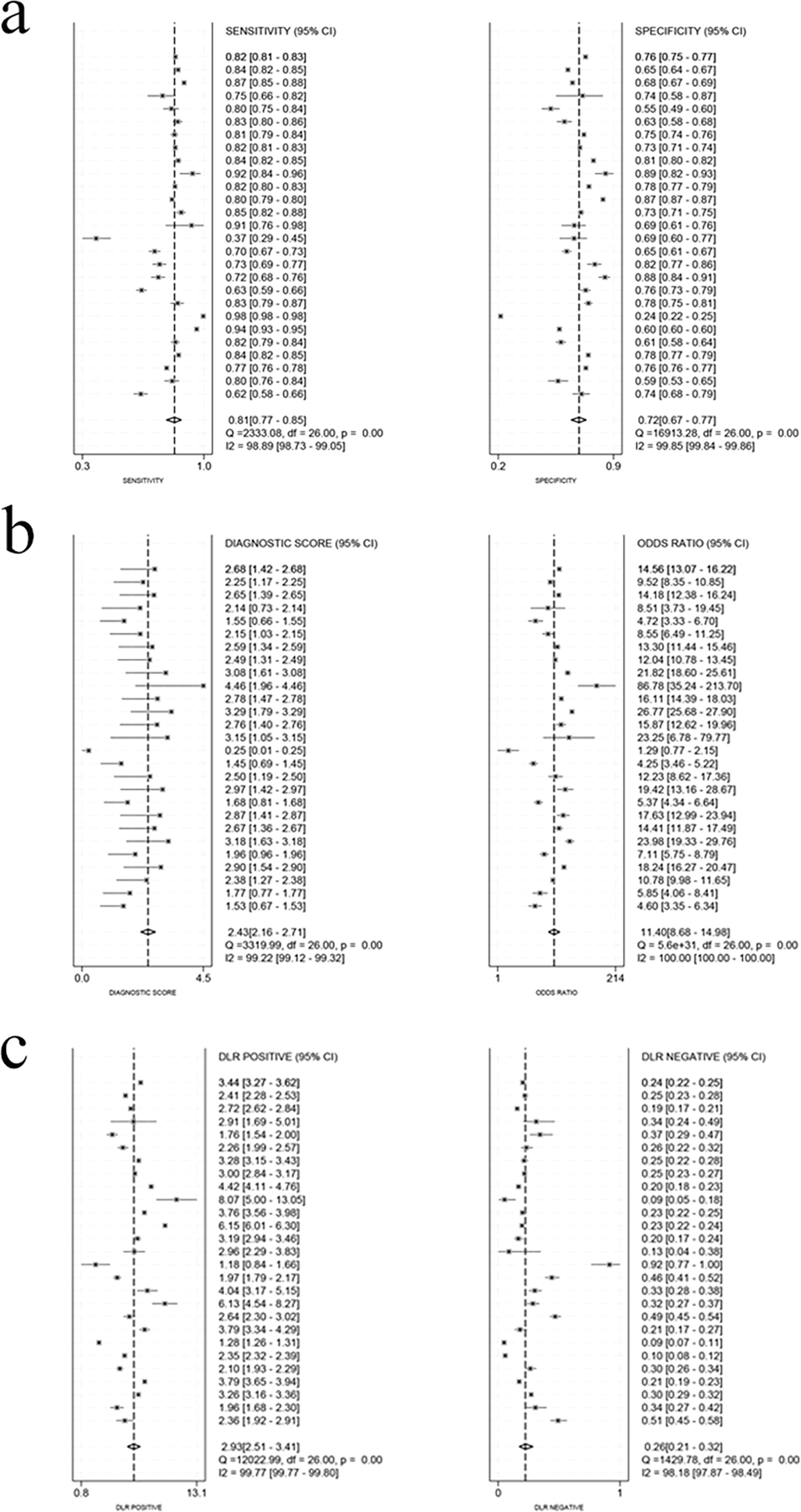

3.4.3Diagnostic efficacyThe threshold effect test was conducted on all the included studies, and Spearman's coefficient was 0.393 (P = 0.024), suggesting the presence of a threshold effect. To avoid its influence, we repeated the threshold effect test on the studies with and without the cutoff. We found that Spearman's coefficient was -0.281 (P = 0.156) for the studies with the cutoff, indicating no threshold effect; it was 0.886 (P = 0.019) for the studies without the cutoff, indicating the presence of a threshold effect.

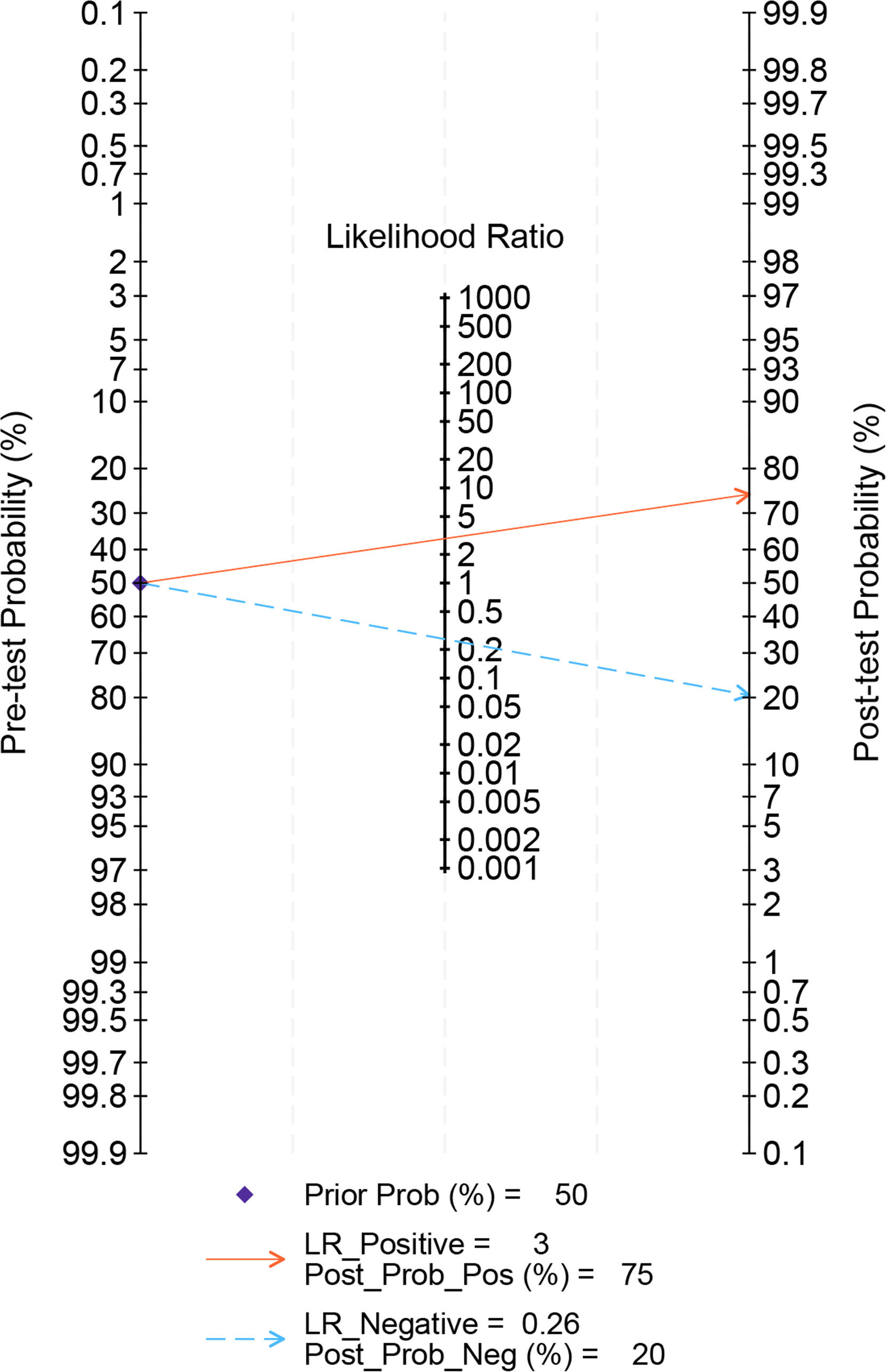

After the studies without the cutoff were ruled out, for the remaining 24 studies [7,10–14,16,18–23,26–30,32–37], the pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive LR, negative LR, and DOR were 0.81 (95% CI 0.77–0.85), 0.72 (95% CI 0.67–0.77), 2.9 (95% CI 2.5–3.4), 0.26 (95% CI 0.21–0.32), and 11 (95% CI 9–15), respectively (Fig. 5). The AUC was 0.83 (95 % CI 0.80–0.86), suggesting higher accuracy of the results (Fig. 6). In addition, regression analyses revealed that country (China and USA), sample size (<1000, 1000–10,000, and >10,000), comorbid diabetes, gold standard for diagnosis (CAP), and cutoff (<100, 100–200, and >200) contributed to the heterogeneity of sensitivity, while country (China), sample size (<1000, 1000–10,000, and >10,000), comorbid diabetes, gold standard for diagnosis (CAP), and cutoff (100–200, and >200) were the sources of heterogeneity of specificity (Fig. S1, Table S5). We also assessed the clinical value of TyG-BMI in the MASLD diagnosis by Fagan nomogram. The pre-test probability was 50 %, and the post-test probability by TyG-BMI rose to 75%, suggesting its high diagnostic value (Fig. 7).

We examined the diagnostic efficacy across sexes. 12 studies [7,10,12,13,15,20,22,24,27,30,35,38] reported this outcome in males and underwent a threshold effect test. After studies with the threshold effect were excluded, Spearman's coefficient was -0.247 (P = 0.415), suggesting no threshold effect. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive LR, negative LR, and DOR were 0.76 (95% CI 0.68–0.83), 0.74 (95% CI 0.69–0.79), 3.0 (95% CI 2.4–3.7), 0.32 (95% CI 0.23–0.44), and 9 (95% CI 6–15), respectively. The AUC was 0.81 (95% CI 0.78–0.85), indicating higher accuracy of the results (Fig. S2).

The diagnostic efficacy in females was reported in 12 studies [7,10,12,13,15,20,22,24,27,30,35,38] and a threshold effect test was conducted. After studies with the threshold effect were excluded, Spearman's coefficient was -0.126 (P = 0.681), suggesting no threshold effect. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive LR, negative LR, and DOR were 0.82 (95% CI 0.73–0.88), 0.80 (95% CI 0.74–0.85), 4.1 (95% CI 3.1–5.4), 0.23 (95% CI 0.15–0.35), and 18 (95% CI 10–33), respectively. The AUC was 0.87 (95% CI 0.84–0.90), indicating higher accuracy of the results (Fig. S3).

3.5Sensitivity analyses and publication biasThe robustness of the results on effect sizes was verified by the sensitivity analysis. The sensitivity analysis results showed that heterogeneity was significant in the study by H. Zou [37], and the results remained robust after this study was excluded, with SMD changing from 4.15 (95 % CI 3.54–4.76) to 3.09 (95 % CI 2.49–3.68). The sensitivity analysis on ORs revealed that two studies [12,13] had greater heterogeneity, and the results remained robust after the exclusion of the two studies, with the OR changing from 1.13 (95% CI 1.11–1.15) to 1.05 (95% CI 1.04–1.07). The sensitivity analysis on diagnostic efficacy revealed that two studies [16,22] had greater heterogeneity, and the results remained robust after exclusion of the two, with the sensitivity changing from 0.81 (95% CI 0.77–0.85) to 0.81 (95% CI 0.78–0.84) and the specificity changing from 0.72 (95% CI 0.67–0.77) to 0.74 (95% CI 0.70–0.77). In the sensitivity analysis on diagnostic performance in males and females, the heterogeneity was significant in two studies [15,22], and the results remained robust after exclusion of the two, with the sensitivity changing from 0.76 (95% CI 0.68–0.83) to 0.77 (95% CI 0.75–0.80) for males and from 0.82 (95% CI 0.73–0.88) to 0.84 (95% CI 0.79–0.87) for females, and the specificity changing from 0.74 (95% CI 0.69–0.79) to 0.76 (95% CI 0.72–0.81) for males and from 0.80 (95% CI 0.74–0.85) to 0.82 (95% CI 0.78–0.86) for females (Fig. S4).

No publication bias was found in the effect size and OR (P > 0.05 in Egger's test), while the diagnostic efficacy displayed publication bias (P < 0.05 in Deeks' test).

4DiscussionTo maintain consistency with the gist of this study, the latest terminology MASLD was utilized. However, we still included relevant studies that used the terms NAFLD and MAFLD during study search and analysis. In the 27 studies included, MASLD patients had significantly higher TyG-BMI than non-MASLD patients. The analysis of the OR in 19 studies revealed that each one-unit increase in TyG-BMI corresponded to a 5% elevation of the MASLD risk. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of TyG-BMI in the MASLD diagnosis were 0.81 and 0.72, respectively, in 24 studies. No threshold effect of TyG-BMI was found in either males or females in sex-stratified analyses (12 studies each); the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.76 and 0.74 in males, and 0.82 and 0.80 in females, suggesting better diagnostic efficacy of TyG-BMI in females.

The good predictive value of TyG in MASLD has been verified by several studies. Nayak [39] conducted a meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 121,975 patients and reported the ORs for the association of TyG with MASLD using multivariate analyses, suggesting that TyG is closely linked to the MASLD incidence (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.88–2.97, P < 0.01). Qin. Ling [40] synthesized four cohort studies and eight cross-sectional studies with 105,365 participants (28,788 MASLD and 76,577 non- MASLD cases), and found that the MASLD risk becomes 2.84 times higher for every one-unit increase in TyG (95% CI 2.01–4.01), suggesting a great association between the two; for each one-unit increase in TyG, the MASLD risk in women is 1.6 times that in men; BMI is a key factor influencing the prediction of TyG for MASLD. These findings offer a basis for TyG plus BMI for predicting the MASLD risk. Khamseh et al. [8] found that TyG-WC is more strongly associated with MASLD (AUC 0.693, 95% CI 0.617–0.769) and fibrosis (AUC 0.635, 95% CI 0.554–0.714) than other indicators (e.g. WC, BMI, and TyG). However, a prospective study by Ziping Song et al. [41] on the relations of CMI, AIP, TyG, TyG-BMI, TyG-WHtR, and TyG-WC with the MASLD incidence revealed that TyG-BMI is a better predictor of MASLD as shown in time-dependent ROC curves (C-index: 0.768, 95% CI 0.762–0.774). According to an NHANES-based study (2025) [37], TyG-BMI outperforms TyG, visceral adiposity index, and fibrosis-4 index in the predictive efficacy (AUC 0.820, 95% CI 0.810–0.831), indicating its potential for early identification of MASLD, especially when the cutoff is >180.71 (sensitivity = 0.835, specificity = 0.653).

We calculated the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of TyG-BMI as 0.81 (95% CI 0.77–0.85) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.67–0.77), respectively. H. Hu [16] put forward a dual cutoff strategy among 14,280 patients, i.e., MASLD can be precisely ruled out under a low cutoff of TyG-BMI (182.2) (negative predictive value: estimated as 96.9%, validated as 96.9%), whereas MASLD can be efficiently identified under a high cutoff of TyG-BMI (224.0) (positive predictive value: estimated as 70.7%, validated as 70.1%). Moreover, H. Hu [16] also conducted external validation in 183,730 patients and confirmed that TyG-BMI has a sensitivity of 89.2% and a specificity of 70.1% when its cutoff is set to 182.2, and a sensitivity of 41.8% and a specificity of 96.3% when its cutoff is set to 224.0. It can also be seen that MASLD can be ruled out or diagnosed under a low or high cutoff, respectively. A.H. Kim et al. [24] also verified the superiority of TyG-BMI in 22,391 participants in Korea (8246 MASLD and 14,145 non-MASLD cases): TyG-BMI possesses a higher AUC value (0.867) than TyG, FLI, and TyG-WC for the MASLD diagnosis, with a specificity and sensitivity of 0.723 and 0.863, especially in females, consistent with our findings. Due to small sample sizes, however, variations in results were present in some of the included studies such as Nong Li et al. [10] (sensitivity = 0.622), and A. S. Bockarie et al. [25] (sensitivity = 0.14, specificity = 0.974).

The pathogenesis of MASLD is closely linked to several metabolic factors. Weight gain, central obesity, and IR are key risk factors for MASLD [42]. As a central role in MASLD [43], IR contributes to liver fat deposition via multiple mechanisms: First, IR prompts the conversion of excess glucose into fat while increasing triglyceride and promoting lipolysis, thus elevating free fatty acids (FFAs) [44]. Then excess FFAs enter the liver through the blood circulation to enhance liver fat synthesis and deposition. In addition, IR weakens insulin sensitivity and impairs insulin signaling, leading to a sustained increase in blood glucose. As a result, both insulin secretion and appetite are stimulated, creating a vicious cycle of high carbohydrate intake [45]. Notably, excess FFAs also restrain glucose uptake by skeletal muscles and hepatocytes, further worsening the disturbance of glucose metabolism [46–48].Besides, body weight is another important factor, and the MASLD risk greatly rises in the overweight or obese. A meta-analysis revealed that the MASLD risk in the obese is 3.5 times that in the non-obese, and BMI possesses an obvious dose-dependent relation with MASLD [49].

The pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of MASLD greatly vary across sex. Longitudinal studies have shown that the incidence of NAFLD is generally higher in men than in women [50–56]. Notably, liver damage and inflammation are more severe in premenopausal women [57,58], but the risk of liver fibrosis is lower than in men and postmenopausal women [59,60], suggesting that sex hormones exert multidirectional regulatory effects on the pathogenesis of NAFLD. At the mechanism level, estrogen may achieve protective effects through multiple pathways: first, it can increase the number of T cells and regulatory T cells, thereby modulating hepatic inflammatory responses; second, it can suppress lipolysis and enhance insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue [61–63], reducing excessive transport of fatty acids to the liver [62,63]. Additionally, higher adiponectin levels in premenopausal women may help mitigate the adverse metabolic effects of ectopic fat accumulation [64,65]. Metabolically, postmenopausal women and men are more prone to metabolic syndrome than premenopausal women [66]. The effects of sex hormones exhibit sexual dimorphism, i.e., androgen excess in women contributes to abdominal obesity and metabolic dysfunction, while androgens in men exert metabolic protective effects [67]. The protective effect of estrogen against liver fibrosis is verified by the available evidence [68]. At present, the specific mechanisms underlying sex differences in the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of MASLD remain unclear, which may be closely related to sex differences in the severity of obesity, metabolic risk factors, and body fat distribution [64,69].

For the IR assessment, the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique is the gold standard [70,71], but it is complex in operation, so fasting insulin-based noninvasive indicators have been increasingly applied in clinical practice. Among them, TyG has been recognized as an alternative biomarker for IR due to its good sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, composite indicators (e.g., TyG-BMI and TyG-WC) are superior to TyG alone in the accurate prediction of MASLD [72–74]. The main reason is that BMI reflects generalized obesity, while waist circumference (WC) is more reflective of visceral fat deposition, both of which are closely associated with IR, metabolic dysfunction, and hepatic steatosis.

TyG-BMI, a composite indicator integrating IR and generalized obesity [75], serves as a reliable tool for the early identification of MASLD. It enables rapid risk assessment and significantly enhances the efficiency of MASLD screening in primary care settings. Due to simple and cost-efficient characteristics, this indicator is particularly suitable for high-risk groups (e.g., patients with prediabetes, and central obesity), which can help achieve precise intervention and long-term health management, ultimately reducing the risk of progressing to severe complications (liver fibrosis and cirrhosis) and ameliorating the long-term prognosis.

Some limitations are worth noting in this study. First, although we conducted subgroup analyses, the great heterogeneity observed could not be explained by country, sample size, cutoff, comorbid diabetes, and the gold standard for diagnosis. Therefore, other sources of heterogeneity may be present such as differences in testing methods, but further discussion failed to be made due to data limitations. Second, the diagnostic methods varied across the included studies, with some using ultrasound and some using controlled attenuation parameter (CAP), which may produce biases in diagnostic accuracy. Although liver biopsy is the gold standard for MASLD diagnosis, it is difficult to implement in epidemiological studies due to ethical and practical constraints [76,77]. Current evidence suggests that ultrasound and CAP, as non-invasive diagnostic techniques, both demonstrate good diagnostic efficacy for MASLD [78]. Third, most of the included studies were cross-sectional in design, and evidence from prospective cohort studies was lacking, thus failing to validate the predictive value of TyG-BMI in the MASLD progression. In addition, the TyG-BMI cutoff greatly varied across studies, so we should stay cautious in interpreting the results. Notably, the included studies were primarily from Asia, which may restrict the generalizability of the results, so more data from other regions need to be further included. Finally, some studies had a high risk of bias (methodological quality) such as Y. Yang [14], Y. Xue [21], Q. Zhang [31], H. Zou [29], H. Peng [20], and G.T. Sheng [13], possibly affecting the reliability of the study conclusions.

To address these limitations, large-sample, multicenter prospective cohort studies are required in the future to further validate the causality between TyG-BMI and MASLD and to clarify the former's predictive value. Moreover, a consistent gold standard for diagnosis should be determined to enhance the accuracy. In addition, TyG-BMI can be combined with other biomarkers or clinical indicators for a combined diagnostic model, thereby further improving its diagnostic efficacy on MASLD. In this way, the clinical value of TyG-BMI in the MASLD screening and diagnosis can be more fully assessed.

5ConclusionsTyG-BMI, a cost-efficient and convenient indicator, exhibits good diagnostic value in MASLD, especially in females. The performance of TyG-BMI greatly varies between MASLD and non-MASLD patients, suggesting its better diagnostic discrimination. To further enhance the diagnostic accuracy, a combination of TyG-BMI with other related indicators (e.g., liver function indicators, inflammatory markers) for a more perfect diagnostic model is recommended in the future. A combined diagnostic strategy is expected to raise the efficiency of early screening for MASLD and offer a more reliable basis for early prevention and intervention.

Data availabilityThe original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

FundingThe authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed to the study conception and design. Writing - original draft preparation: Kexin Du; Writing - review and editing: Feng Jiang; Conceptualization: Yafang Huang; Methodology: Kexin Du; Formal analysis and investigation: Yanhui Yu, Jianrong Guo, Jianmei Feng; Resources: Feng Jiang; Supervision: Feng Jiang, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

None.