Liver resection is the treatment of choice for many primary and secondary liver diseases. Most studies in the elderly have reported resection of primary and secondary liver tumors, especially hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal meta-static cancer. However, over the last two decades, hepatectomy has become safe and is now performed in the older population, implying a paradigm shift in the approach to these patients.

Material and MethodsWe retrospectively evaluated the risk factors for postoperative complications in patients over 65 years of age in comparison with those under 65 years of age after liver resection (n = 360). The set comprised 127 patients older than 65 years (35%) and 233 patients younger than 65 years (65%).

ResultsIn patients younger than 65 years, there was a significantly higher incidence of benign liver tumors (P = 0.0073); in those older than 65 years, there was a significantly higher incidence of metastasis of colorectal carcinoma to the liver (0.0058). In patients older than 65 years, there were significantly more postoperative cardiovascular complications (P = 0.0028). Applying multivariate analysis, we did not identify any independent risk factors for postoperative complications. The 12-month survival was not significantly different (younger versus older patients), and the 5-year survival was significantly worse in older patients (P = 0.0454).

ConclusionIn the case of liver resection, age should not be a contraindication. An individualized approach to the patient and multidisciplinary postoperative care are the important issues.

Life expectancy worldwide has increased greatly in recent decades, resulting in an aging population. This process is due to several factors, such as a higher past fertility rate compared with that of the present, reduced child mortality, the implementation of governmental policies to support the elderly, improvements in working conditions, access to public health services, and the best quality of life. The improvement of social conditions and incessant development of technological and medical knowledge also contribute to this picture.1

Within the context of cancer treatment, liver resection is the treatment of choice for many primary and secondary diseases of the liver. Most studies in the elderly undergoing this procedure have reported resection of primary and secondary liver tumors, especially for hepatocellular carcinomas and colorectal metastatic cancer.2 However, it has been observed in the last two decades that hepatectomy has become safe and is now performed in the older population, implying a paradigm shift in the approach to these patients.3 On a standard basis, we classify geriatric patients into the following age groups: young-old age (65-74 years), middle-old age (75-84 years), and old-old age (85 years and older).4,5

Cardiac complications belong to the most common and most serious postoperative problems. The strongest predictors of adverse cardiac outcomes are recent myocardial infarction, uncompensated congestive heart failure, unstable ischemic heart disease, and certain cardiac rhythm disorders. The major clinical predictors are unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated congestive heart failure, significant arrhythmias, and severe valvular disease. Intermediate clinical predictors are mild angina pectoris, prior myocardial infarction, compensated or prior congestive heart failure, and diabetes mellitus. Minor clinical predictors are advanced age, abnormal ECG findings, rhythm other than sinus, low functional capacity, history of stroke, and uncontrolled systemic hypertension.

Renal disease has an important impact on patient morbidity and postoperative course. Renal disease may not be considered in older patients because a reduction in creati-nine clearance is usually not reflected in a rise in the serum creatinine level. The serum creatinine level must be adjusted for age and the accompanying decrease in lean body mass. Preoperative renal status is the best universal predictor of postoperative renal failure. Paying close attention to volume status, aggressively treating infections, and avoiding the use of nephrotoxic drugs are critical to minimizing postoperative renal deterioration in older adults.6

In their analysis, Kassin, et al. evaluated the most frequent postoperative complications with readmission in more than 1,000 patients. The most common reasons for readmission were gastrointestinal problems. Problems or complications accounted for 27.6% of readmissions, surgical infection for 22.1%, and failure to thrive or malnutrition for 10.4%. Comorbidities associated with the risk of readmission included disseminated cancer, dyspnea, and preoperative open wound (P < 0.05 for all variables). The surgical procedures associated with high rates of readmis-sion included pancreatectomy, colectomy, and liver resection. The postoperative occurrences resulting in increased risk of readmission were blood transfusion, postoperative pulmonary complication, wound complication, sepsis/ shock, urinary tract infection, and vascular complications. Multivariable analysis demonstrates that the most significant independent risk factor for readmission is the occurrence of any postoperative complication (odds ratio = 4.20; 95% CI, 2.89-6.13).7

The aim of this study is to determine of the incidence of postoperative complications after liver resection in geriatric patients compared to patients younger than 65 years

Material and MethodsIn a retrospective analysis of 360 patients who underwent liver resection at the Surgery Clinic and Transplant Center of the University Hospital Martin during the years 2004-2013, we identified the cause of resection (according to histological findings) and type of resection: large (hemihepatectomy or extended hemihepatectomy), small (resection of segments), or radiofrequency ablation (the technique was performed when the finding in the liver could not be resected. In our clinic we perform this technique by using open way). We divided the whole set into two groups according to age at the time of surgery (patients younger than 65 years and patients older than 65 years). In each patient, we detected presence of postoperative complications (cardiovascular, septic, surgical and other, including hepatic failure, hepatorenal syndrome, and acute kidney failure) and their relation to the type of resection and age. Postoperative complications were defined as complications that developed within 30 days after the operation. To evaluate the monitored parameters (his-tological findings, type of resection, age at the time of surgery, and gender) as independent risk factors for the development of postoperative complications, we applied multivariate analysis. At the end, we determined the 12-month and 5-year survival of the patients in both monitored groups.

In our analysis there were no patients who underwent transarterial chemoembolization or radioemobolization.

We used the certified statistical program MedCalc version 13. 1. 2. for statistical evaluation and we applied the following statistical analyses: Student's t-test, χ2 test, correlation coefficient, Cox proportional hazard model, and Kaplan-Meier curves of survival. We considered values of P < 0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

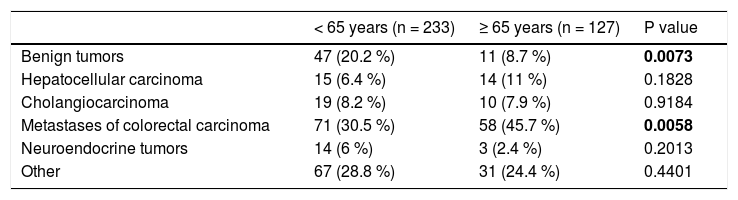

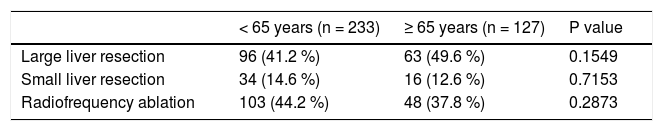

ResultsThe average age of the whole set of patients was 58.7 years ± 11.7. The set was composed of 194 men (53.9%) and 166 women (46.1%). The average age at the time of surgery was significantly higher in men than in women: in men it was 59.9 ± 10.7 years, and in women it was 57.2 ± 12.6 years (P = 0.0287). The set comprised 127 patients older than 65 years (35%) and 233 patients younger than 65 years (65%). The group of patients older than 65 years comprised 98 patients (77%) aged 65-74 years and 29 patients (23%) aged 75-84 years. There were no patients older than 85 years of age. The group of patients older than 65 years comprised 49 women (38.6%) and 78 men (61.4%), the average age of women was 71.3 ± 4.8 years and that of men was 69.9 ± 4 years (P = 0.0782). In the individual groups of patients (younger than 65 years and older than 65 years), we detected the following histological findings (Table 1). In patients younger than 65 years, there was a significantly higher incidence of benign liver tumors in comparison with patients older than 65 years. Conversely, in patients older than 65 years, we identified a significantly higher incidence of patients with metastases of colorectal carcinoma in the liver. In total, 209 liver resections and 151 radiofrequency ablations were carried out in the whole set of patients. In patients younger and older than 65 years, there were 130 (55.8 %) and there were 79 (62.2 %) liver resections, respectively (P = 0.2873) (Table 2).

Distribution of the set of patients according to histological findings.

| < 65 years (n = 233) | ≥ 65 years (n = 127) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign tumors | 47 (20.2 %) | 11 (8.7 %) | 0.0073 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 15 (6.4 %) | 14 (11 %) | 0.1828 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 19 (8.2 %) | 10 (7.9 %) | 0.9184 |

| Metastases of colorectal carcinoma | 71 (30.5 %) | 58 (45.7 %) | 0.0058 |

| Neuroendocrine tumors | 14 (6 %) | 3 (2.4 %) | 0.2013 |

| Other | 67 (28.8 %) | 31 (24.4 %) | 0.4401 |

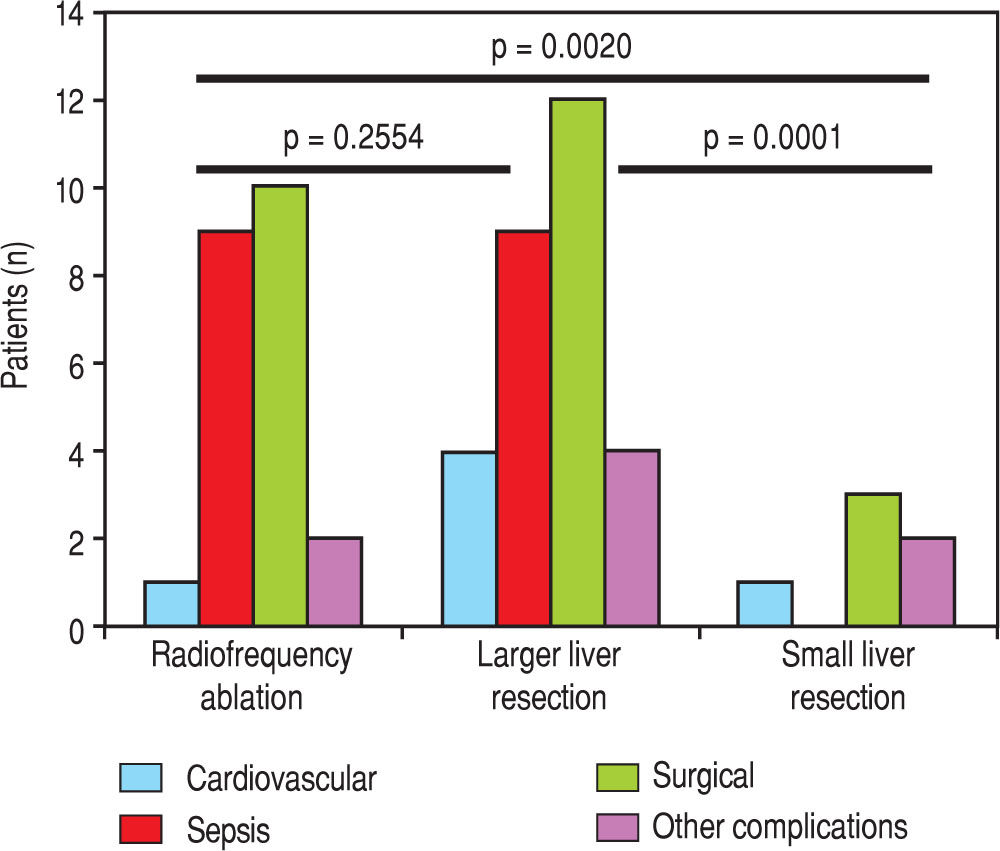

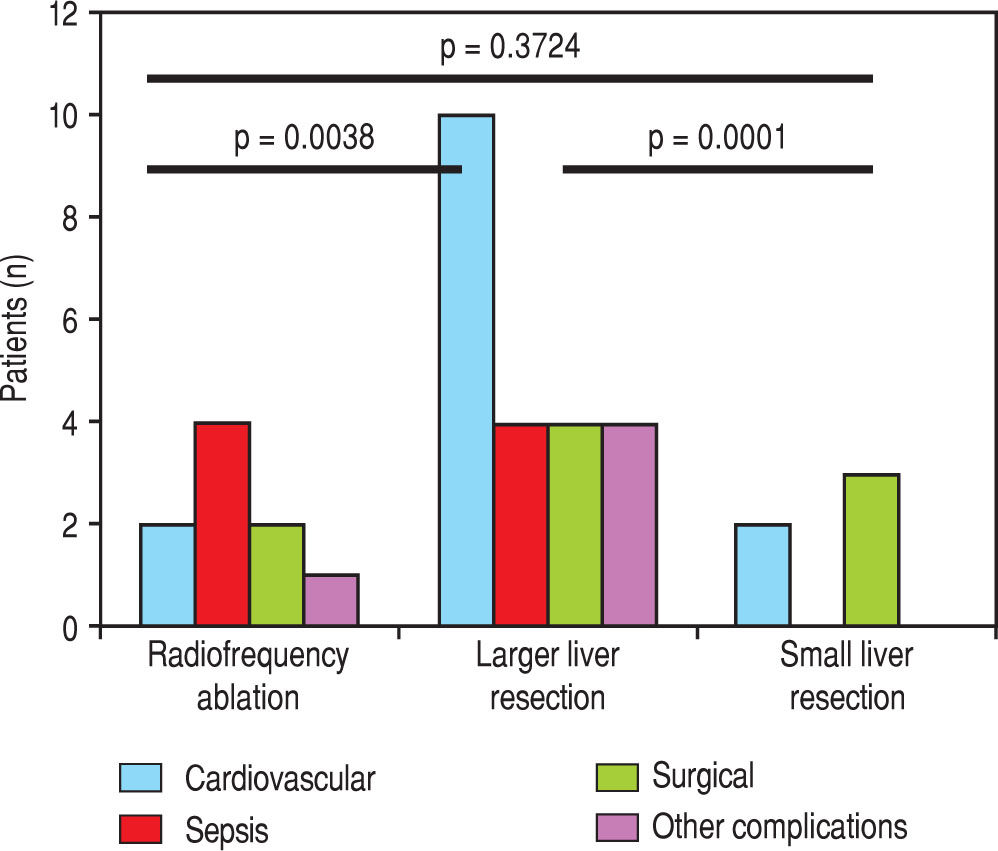

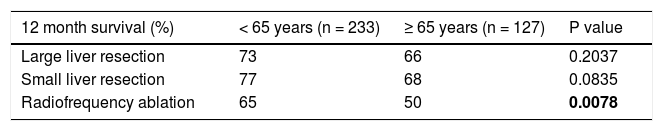

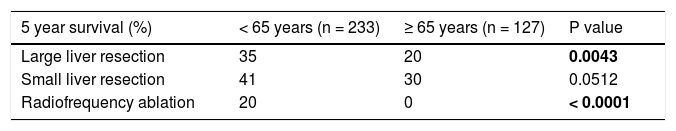

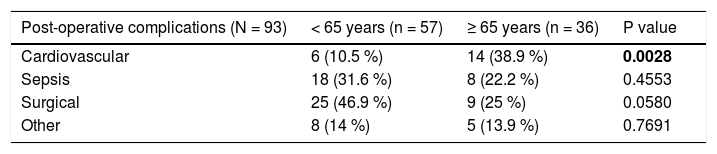

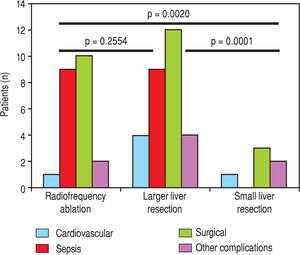

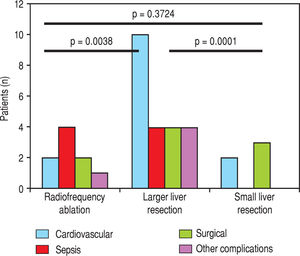

We evaluated the 12-month and 5-year survival in individual groups of patients according to the type of liver resection (Table 3 and Table 4, Figure 1 and Figure 2). We discovered that patients with radiofrequency ablation who were older than 65 years had the worst survival (both the 12-month and the 5-year). After a large liver resection, patients older than 65 years had a significantly worse 5-year survival in comparison with patients younger than 65 years. In patients younger and older than 65 years, we identified post-operative complications of any kind in 57 (24.5 %) and 36 (28.3 %) patients, respectively (P = 0.5086). We divided the complications into cardiovascular (cardiac failure, rhythm disorders), sepsis, surgical complications, and other (hepatic failure, hepatorenal syndrome, acute kidney failure) (Table 5). We discovered a significantly higher incidence of cardiovascular complications in patients older than 65 years.

Next, we identified individual complications depending on the type of resection (large, small, radiofrequency ablation; Figure 1 and Figure 2). We discovered that patients younger than 65 years had the statistically smallest number of complications after a small liver resection. Statistically, the highest number of complications in patients older than 65 years occurred in the case of large liver resections.

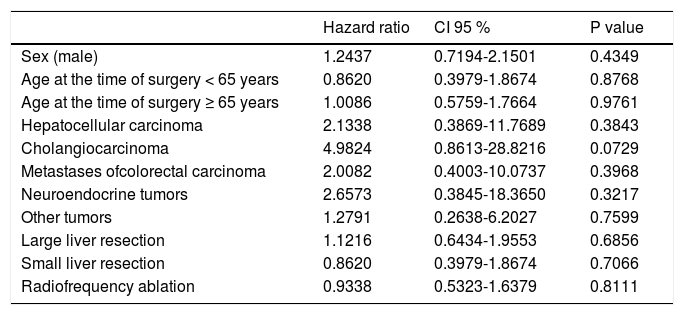

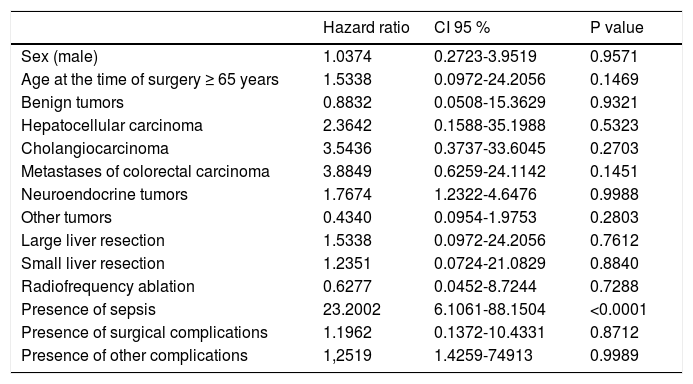

Using multivariate analysis (Table 6), we identified the monitored parameters as independent risk factors for the development of complications after liver resection. In cases of cardiovascular complications of liver resection, by using multivariate analysis we have found, that only presence of sepsis is an independent risk factor for development of cardiovascular complications after liver resection (Table 7).

Multivariate analysis-identification of the independent risk factors for post-operative complications of liver resections.

| Hazard ratio | CI 95 % | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 1.2437 | 0.7194-2.1501 | 0.4349 |

| Age at the time of surgery < 65 years | 0.8620 | 0.3979-1.8674 | 0.8768 |

| Age at the time of surgery ≥ 65 years | 1.0086 | 0.5759-1.7664 | 0.9761 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2.1338 | 0.3869-11.7689 | 0.3843 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 4.9824 | 0.8613-28.8216 | 0.0729 |

| Metastases ofcolorectal carcinoma | 2.0082 | 0.4003-10.0737 | 0.3968 |

| Neuroendocrine tumors | 2.6573 | 0.3845-18.3650 | 0.3217 |

| Other tumors | 1.2791 | 0.2638-6.2027 | 0.7599 |

| Large liver resection | 1.1216 | 0.6434-1.9553 | 0.6856 |

| Small liver resection | 0.8620 | 0.3979-1.8674 | 0.7066 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 0.9338 | 0.5323-1.6379 | 0.8111 |

Multivariate analysis-independent risk factors for post-operative cardiovascular complications of liver resections.

| Hazard ratio | CI 95 % | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 1.0374 | 0.2723-3.9519 | 0.9571 |

| Age at the time of surgery ≥ 65 years | 1.5338 | 0.0972-24.2056 | 0.1469 |

| Benign tumors | 0.8832 | 0.0508-15.3629 | 0.9321 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2.3642 | 0.1588-35.1988 | 0.5323 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 3.5436 | 0.3737-33.6045 | 0.2703 |

| Metastases of colorectal carcinoma | 3.8849 | 0.6259-24.1142 | 0.1451 |

| Neuroendocrine tumors | 1.7674 | 1.2322-4.6476 | 0.9988 |

| Other tumors | 0.4340 | 0.0954-1.9753 | 0.2803 |

| Large liver resection | 1.5338 | 0.0972-24.2056 | 0.7612 |

| Small liver resection | 1.2351 | 0.0724-21.0829 | 0.8840 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 0.6277 | 0.0452-8.7244 | 0.7288 |

| Presence of sepsis | 23.2002 | 6.1061-88.1504 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of surgical complications | 1.1962 | 0.1372-10.4331 | 0.8712 |

| Presence of other complications | 1,2519 | 1.4259-74913 | 0.9989 |

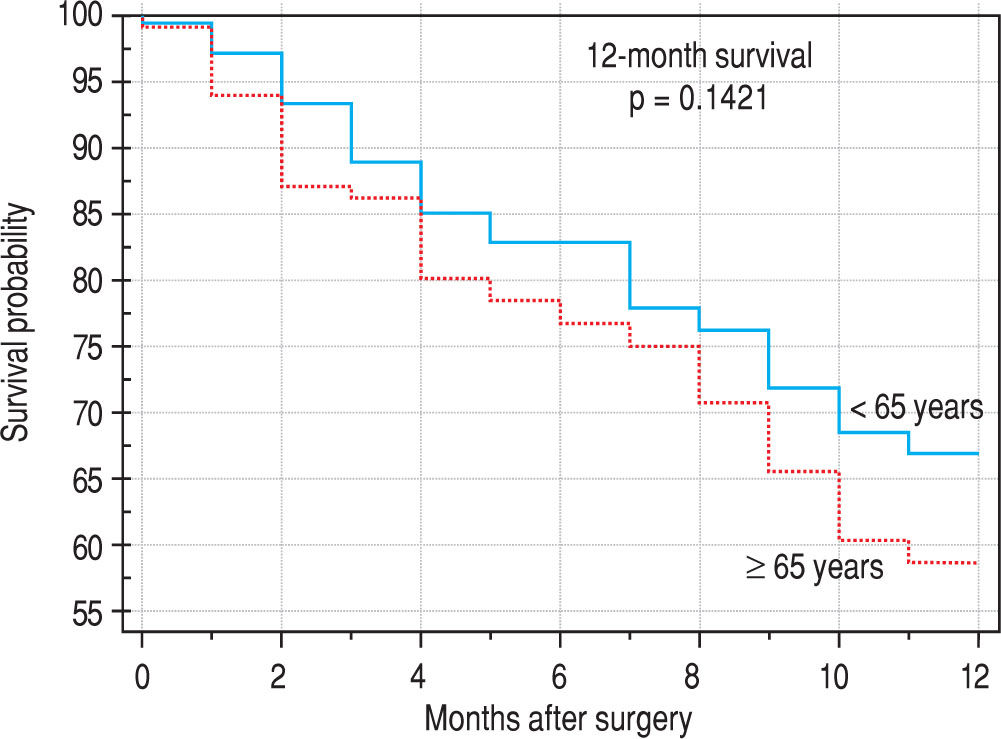

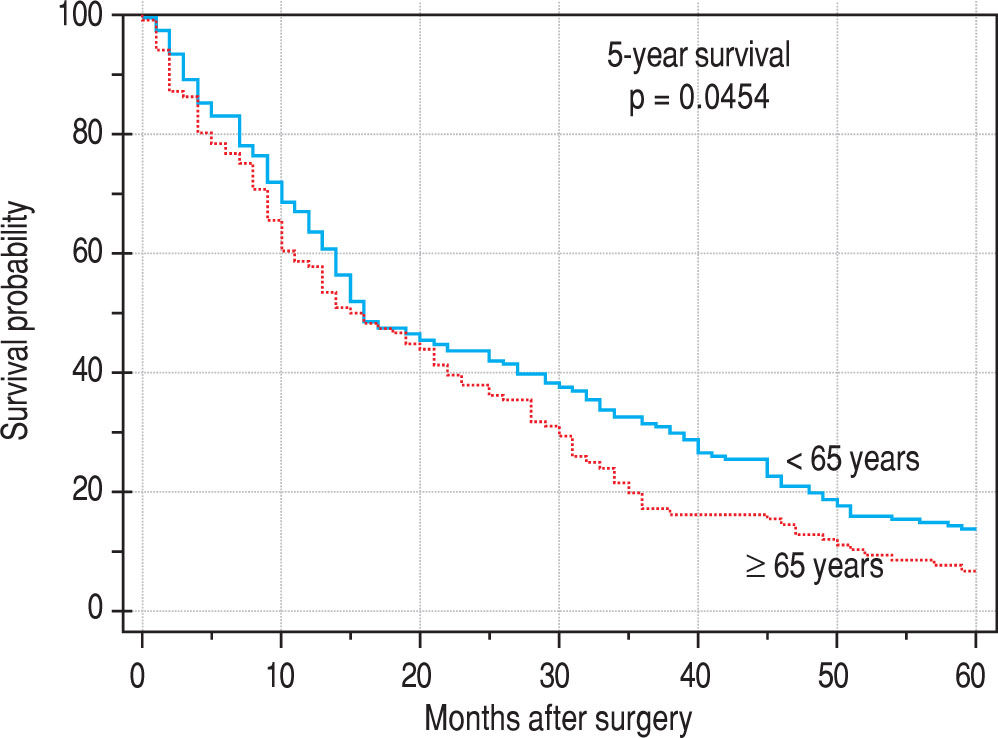

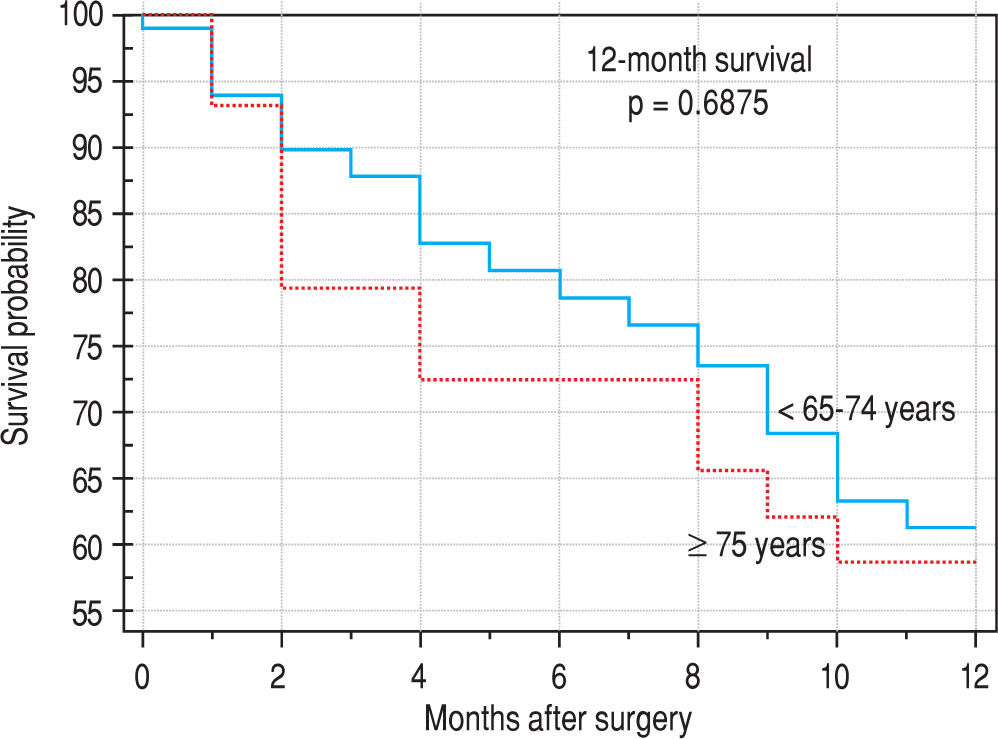

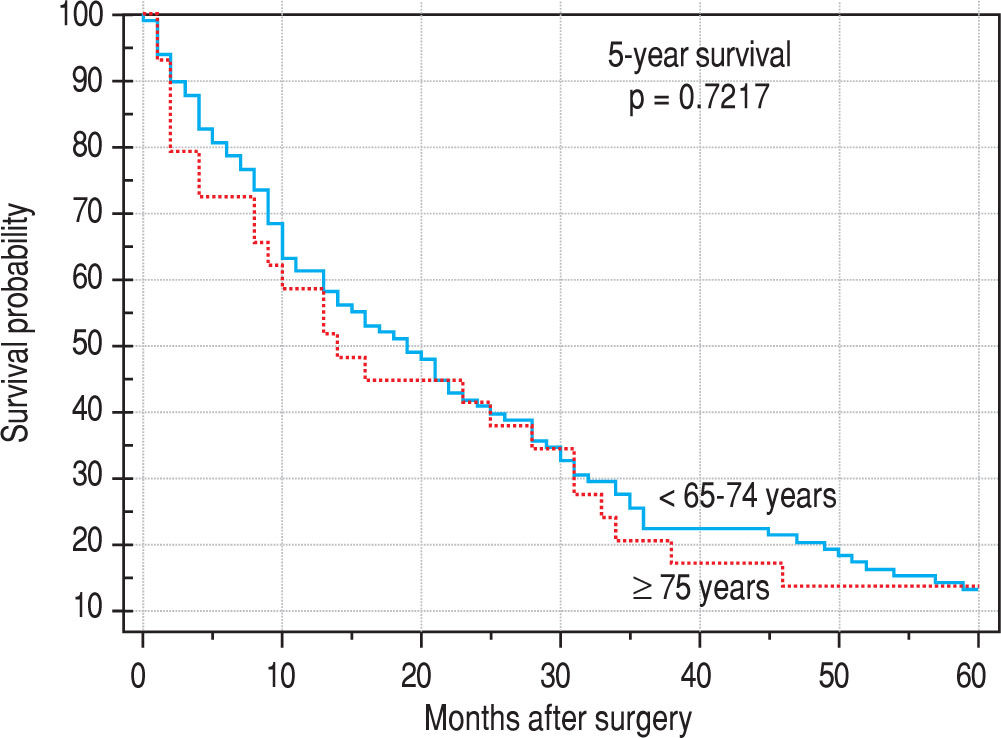

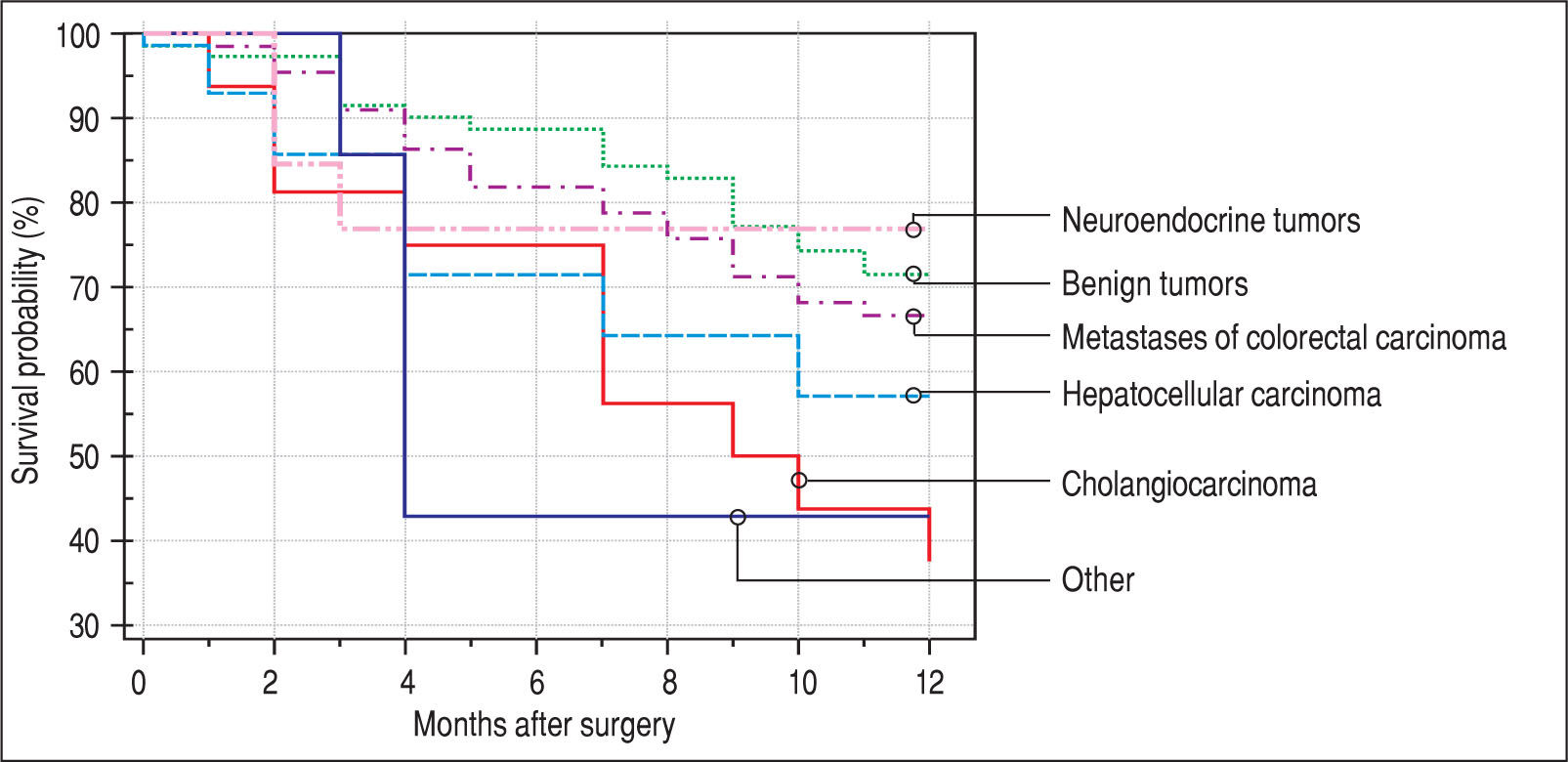

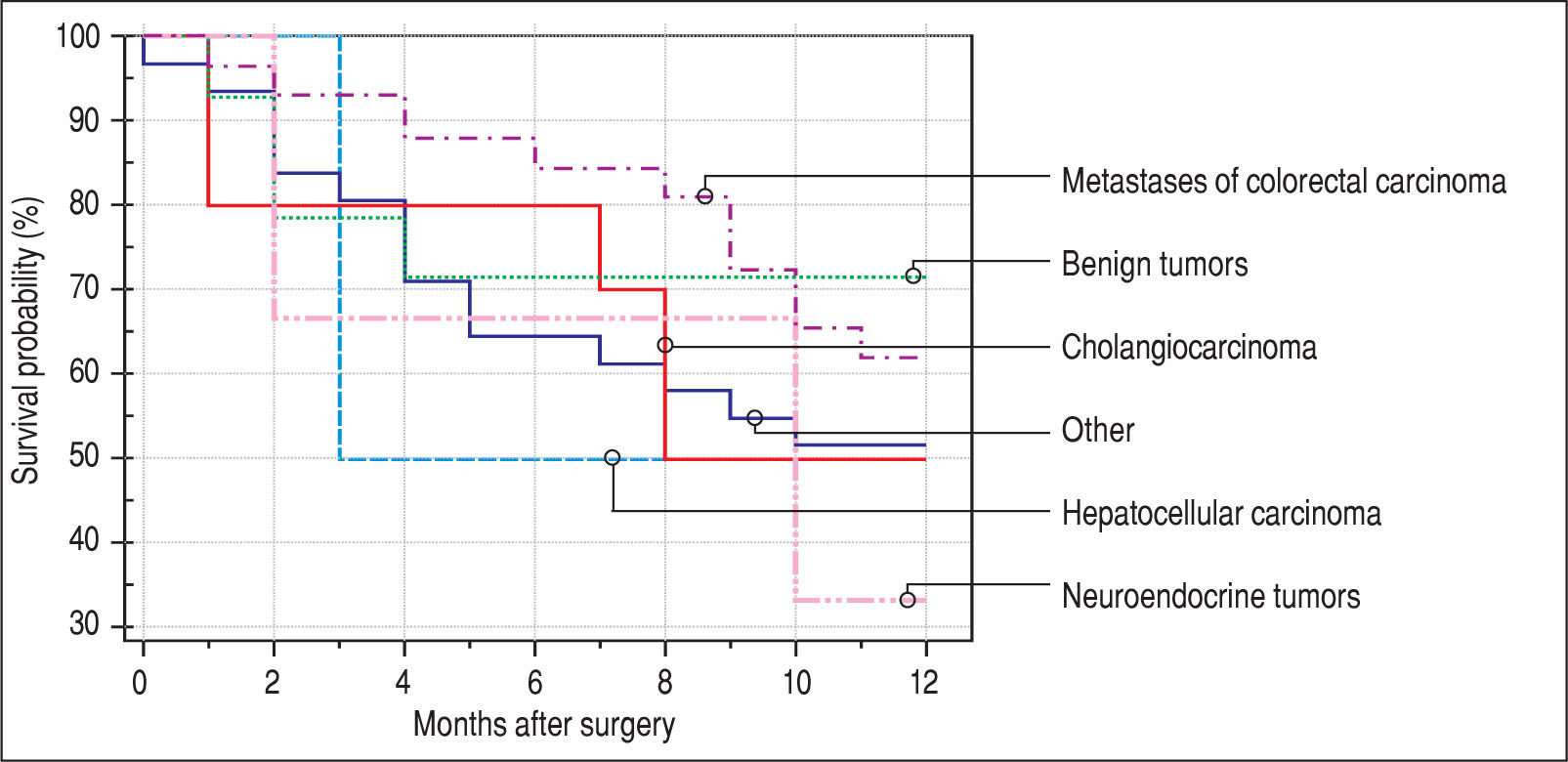

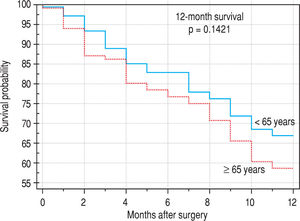

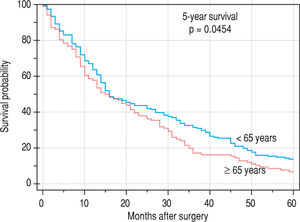

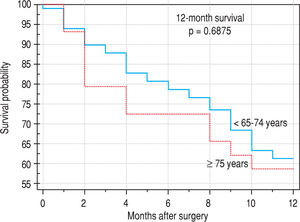

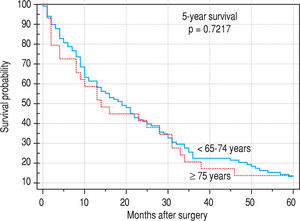

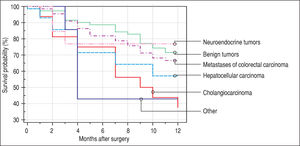

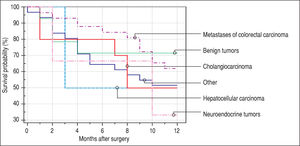

Finally, we identified the 30-day, 12-month and 5-year survival of patients in both groups. The 30-day survival of patients younger than 65 years was 2.6% in comparison with the 6.3% survival of patients older than 65 years (P = 0.7554). The 12-month survival of patients younger than 65 years was 67% in comparison with the 59% survival of patients older than 65 years (P = 0.1421). We have recorded a statistically significant difference in 5-year patient survival. In patients younger than 65 years, 5-year survival was 15% and in those older than 65 years, it was 9% (P = 0.0454; Figure 3and Figure 4). We also evaluated survival in the 65 to 74-year age group versus the over 75-year age group. The 12-month survival was 62% in patients from 65 to 74 years. In patients older than 75 years, it was 59% (P = 0.6875). The 5-year survival was equal in both groups: 14% (P = 0.7217; Figure 5 and Figure 6). The worst 12-month survival in group of younger patients had the patients with HCC and cholangiocarcinomas (Figure 7). 12-moth survival of patients older than 65 years according to histological finding is in Figure 8.

DiscussionTreatment by surgical resection of primary and secondary liver malignancies is the only curative modality with the effect of long-term survival. Only 10-15% of patients with primary malignant liver disease (in 90% of cases, hepatocellular carcinoma - HCC) are indicated to undergo resection. Metastatic diseases of the liver are the most frequent malignancies in developed countries, and liver is the second most frequent site for spread of the primary process after the lymphatic nodules. 50-60% of patients have metastatic liver disease at the time of diagnosis of the primary tumor and out of this number, only about 20% of cases are resectable.8

The average life span is increasing dramatically, mainly in developed countries. With increasing age, the number of patients requiring treatment for primary and secondary tumors of the liver also rises. According to Bhangui, et al., liver resection is indicated in 2-20% of patients older than 70 years in cases of metastases of colorectal carcinoma. This may be related to a preference for palliative care in older patients. However, in view of some other studies, age is not an important factor in patient survival after liver resection in terms of long-term prognosis.9

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma increases with age. In the United States, the average age at the time of diagnosis is 65 years, and 74% of affected patients are men.10 The 5-year survival after resection in cases of HCC is from 5% to 46%.8 Cholangiocarcinoma is diagnosed mainly in patients between 60 and 70 years of age. The 5-year survival ranges from 2% to 30%.11 Colorectal cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world.12 It accounts for over 9% of all cancers.13 The likelihood of a colorectal cancer diagnosis increases progressively starting at age 40, rising sharply after age 50.14 More than 90% of colorectal cancer cases occur in people aged 50 and older.14,15 The rate of occurrence is more than 50 times higher in persons aged 60 to 79 years than in those younger than 40 years.14, 16 The 5-year survival after liver resection is 35-40% in the case of colorectal carcinoma.8

The average age at the time of tumor discovery is between 55 and 60 years. The 5-year survival of patients with neu-roendocrine tumors after liver resection is 20%-43%.17 In our patients, we noticed a higher incidence of metastases of colorectal carcinoma in older patients (older than 65 years), compared with patients younger than 65 years, which corresponds to the data from large registers. On the contrary, in the case of younger patients, we noticed a significantly higher incidence of benign tumors when compared with older patients.9 The 12-month survival of the patients in our set was numerically better in the case of younger patients; however, there was no statistically significant difference when compared with older patients. We detected a difference in the case of 5-year survival in younger patients; this is probably connected to the higher incidence of benign tumors in this group.

The survival of patients in our set was without significant difference in the age groups from 65 to 74 years and older than 75 years. This is in agreement with the present trend of surgical solutions in older patients after scheduled complex internal preparation. On the other hand, one needs to be cautious when using ‘aggressive therapies’ and ‘extended criteria’ in the aged. Ageing is associated with a myriad of physiological and functional changes that may compromise the ability of elderly patients to tolerate these therapies. Liver surgery is not without complications, and the need to balance the risks and costs against the potential improvement in survival in the elderly continues to leave many clinicians reluctant to propose surgical resection in these patients.9

In by study Junejo, et al., age was a statistically significant predictor of postoperative complications in a sample of 204 patients.18 In a study of abdominal operations, the mortality rate in patients aged 80-84 years was 3%; the rate was 9% for patients aged 85-89 years, and 25% for those older than 90 years. Advanced age, poor functional status at baseline, impaired cognition, and limited support at home are all risk factors for adverse outcomes. However, when age and severity of illness are directly compared, severity of illness is a much better predictor of outcome compared with age. Emergency operations carry a greater risk than elective operations in all age groups, particularly in elderly persons.6 The authors of Andres et al. identified large liver resection as an independent risk factor for general postoperative complications in a group of 726 patients after liver resection [HR 0.170 (CI 95 % 0.075-0.245), P < 0.001]. Similarly, in our analysis, in patients older than 65 years, postoperative complications were more frequent than in the case of small resection or radiofrequency ablation. In our analysis and also in that of Andres, et al., age was not a risk factor for other general risk factors.19 However, we discovered by observation that significantly more cardiovascular complications occurred in patients older than 65 years.

A practice guideline for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for non-cardiac surgery is proposed by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Task Force. Patients are assessed using a step-wise approach according to clinical predictors, the risk associated with the proposed operation, and functional ca-pacity.20 If the patient has recurrent symptoms or signs but has had recent coronary evaluation, such as angiogram or stress test, with a favorable result, then the surgery is per-formed.6

In the multivariate analysis, we have not evaluated the monitored parameters (histological findings, age, gender, type of resection) as independent risk factors for development of postoperative complications; this is probably connected with the individualized approach to the patient. Liver surgeries in our center are planned in advance in most cases; thus, the patient is perfectly prepared for the surgery by the internist.

ConclusionSurgical treatment of liver metastases or primary tumors is based on liver resection or on applying the ablation method, mainly radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation and interventional radiology (trans-arterial chemoebolization of liver lesions).21-23 Age should not be a contraindication in the case of resection. It is necessary to approach the patient individually and to evaluate the postoperative risks (with respect to the expected range of surgical performance and the patient's comorbidities). The risk of postoperative complications may be reduced by multidisciplinary postoperative care at the intensive care unit (the surgeon, the internist, the hepatologist, and the oncologist).

Abbreviations• HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.