Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has emerged as a major comorbidity among patients with severe mental illness (SMI), particularly those treated with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). These agents induce systemic metabolic disturbances through mechanisms involving adipose tissue dysfunction, mitochondrial injury, and dysregulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. Increasing evidence identifies SGAs as significant contributors to hepatic dysfunction, acting through activation of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), impairment of mitochondrial respiratory function, low-grade inflammation, alterations in the AMPK signaling pathway, and gut microbiota dysbiosis. Collectively, these processes promote hepatic lipid accumulation, insulin resistance, and progression toward non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Furthermore, non-invasive biomarkers such as the Fatty Liver Index (FLI) and FIB-4 score have demonstrated potential utility for early screening and risk stratification in psychiatric populations. Overall, SGAs play a central role in the pathogenesis of MASLD by disrupting mitochondrial homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and gut–liver axis communication. Routine liver monitoring should be integrated into psychiatric care, and future research must focus on preventive and therapeutic strategies that protect hepatic function without compromising mental stability.

MASLD, formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is currently the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, with a prevalence exceeding 30 % and rising due to increasing rates of obesity, physical inactivity, and metabolic dysregulation. MASLD is defined by the presence of hepatic fat accumulation in conjunction with at least one cardiometabolic risk factor, after excluding secondary causes such as significant alcohol intake or other specific liver diseases [1].

The clinical spectrum of MASLD ranges from simple steatosis to more advanced forms, such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), progressive liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2].

The severity of MASLD is influenced by factors including genetic predisposition, dietary patterns, degree of adiposity, insulin resistance, gut microbiota alterations, and hormonal dysregulation. Beyond obesity and insulin resistance, hormones such as growth hormone, thyroid hormones, sex steroids, adrenal hormones, and prolactin play a critical role in regulating hepatic metabolism by modulating lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and inflammatory responses [3].

These metabolic, endocrine, and microbial disturbances generate a particularly vulnerable physiological context for the development and progression of MASLD, especially in individuals exposed to high-risk pharmacological therapies. Among these, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are well-known for their profound impact on energy and lipid metabolism.

SGA use has been shown to triple the risk of developing metabolic syndrome (MetS), with reported prevalence ranging from 32 % to 68 % in exposed patients, compared to 3.3 % to 26 % in non-exposed populations [4]. MetS is a well-established risk factor for MASLD, as it encompasses key metabolic disturbances such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, central obesity, and hypertension, all of which contribute to hepatic steatosis and disease progression. Moreover, individuals with severe psychiatric disorders—particularly schizophrenia and bipolar disorder—have an inherently higher risk of developing MetS, even in the absence of pharmacological treatment, further amplifying their susceptibility to MASLD.

In line with the recent international consensus, this manuscript adopts the term MASLD instead of the previously used NAFLD. However, when referring to prior studies that use the original nomenclature, the term NAFLD is retained for consistency with the cited sources.

1.2Global prevalence and risk factorsSeveral studies have documented a high burden of MASLD in patients with severe mental illness (SMI), such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.

A prospective study conducted in Spain in 2016 reported that 25.1 % of patients with a first episode of psychosis reached a Fatty Liver Index (FLI) ≥60 after three years of antipsychotic treatment, despite the absence of hepatic steatosis at baseline [5]. The FLI is a validated algorithm that estimates the presence of fatty liver based on body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, triglycerides, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels. An FLI ≥60 indicates a high probability of hepatic steatosis. This finding is particularly relevant as it highlights the capacity of antipsychotic therapy to induce NAFLD even in individuals without baseline metabolic risk factors. In addition to FLI, other clinical tools are available to assess MASLD/MASH, including liver enzyme levels (such as alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), imaging techniques like ultrasound or transient elastography, and non-invasive fibrosis scores such as FIB-4, which combines age, AST, ALT, and platelet count. These markers are essential for evaluating liver damage progression in psychiatric patients receiving antipsychotics [150].

Similarly, Koreki et al. (2020) found that the risk of NAFLD was significantly associated with higher cumulative doses of antipsychotics (expressed in chlorpromazine equivalents) and with the use of high-risk metabolic agents such as clozapine and olanzapine [6]. Antipsychotic medications can induce MASLD even in the absence of pre-existing metabolic risk factors. Evidence suggests a dose-dependent relationship between antipsychotic exposure and the risk of developing MASLD.

In a 2017 Chinese study, approximately 50 % of young patients with schizophrenia developed hepatic steatosis after one month or more of treatment [7]. Notably, the study did not explicitly account for potential confounding factors such as diet, physical activity, or environmental influences, which may have impacted the observed association between antipsychotic use and MASLD.

In broader psychiatric populations, the findings remain concerning. A study of 734 psychiatric patients in China reported a steatosis prevalence of 48.7 % and hepatic fibrosis of 15.5 %, both significantly higher than those observed in healthy controls. Key associated factors included age, body mass index (BMI), visceral adiposity, and antipsychotic use [8].

A retrospective analysis of long-term hospitalized patients with schizophrenia revealed a NAFLD prevalence of 54.6 %, correlated with hospitalization duration, obesity, elevated triglyceride levels, and insulin resistance [9]. Likewise, a cohort of 66,273 patients with mental disorders admitted to psychiatric hospitals in Beijing reported an overall NAFLD prevalence of 17.5 %, with higher rates in men and in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder [10].

Interestingly, even in the absence of obesity, psychiatric patients exhibit an elevated risk of NAFLD. In non-obese individuals with schizophrenia, the prevalence reached 23.5 %, suggesting an additional role of genetic and pharmacological factors [11]. A clinical cross-sectional study also found that 41 % of patients with schizophrenia had steatosis detectable via ultrasound [12].

Finally, an additional prospective study showed that, after three years of antipsychotic treatment in patients with a first episode of psychosis, 25.1 % reached FLI values ≥60, indicating significant hepatic steatosis [13].

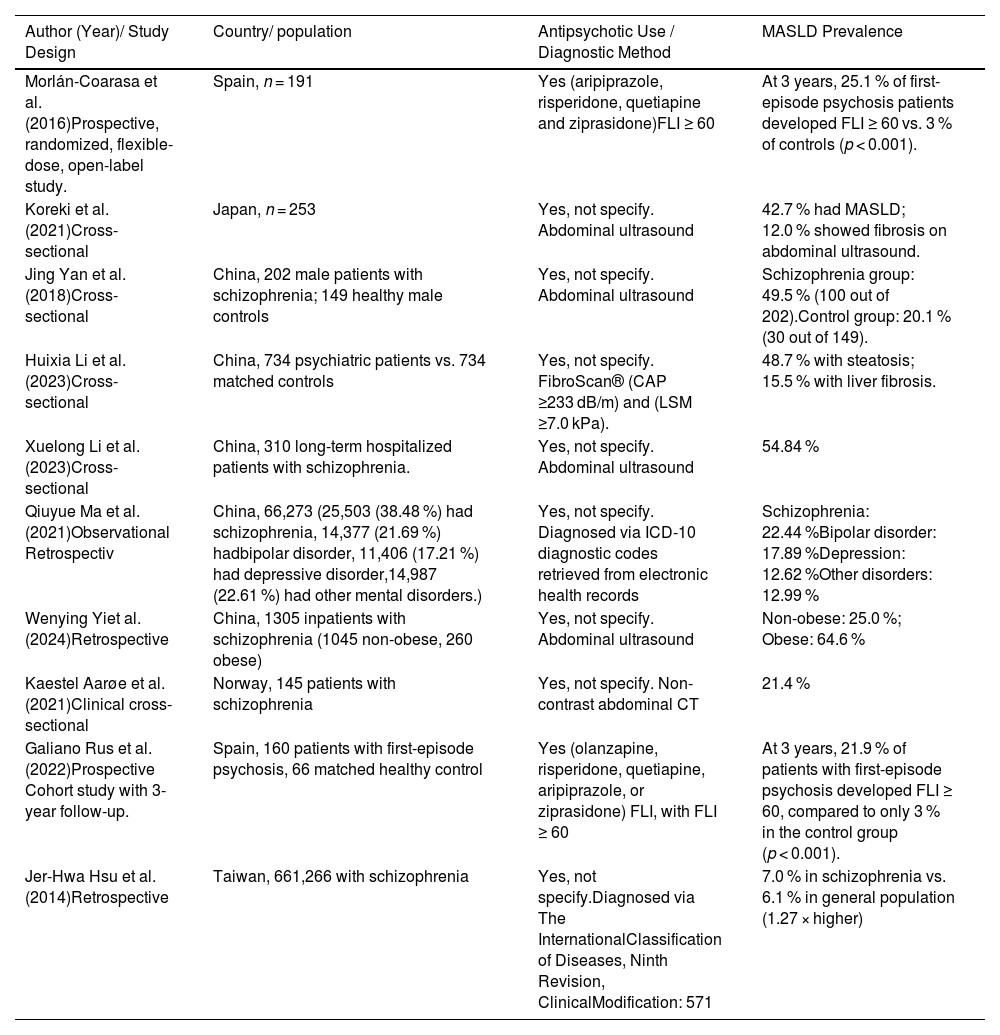

Table 1 compares different studies, highlighting both the diagnostic methods used for MASLD and the characteristics of the populations included, allowing for an appreciation of the methodological and clinical heterogeneity among the reviewed investigations.

Summary of diagnostic approaches and population characteristics in studies on MASLD.

MASLD, Metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease; FLI, Fatty Liver Index; CAP, Crontrolled Attenuation Parameter; LSM, Liver Stiffness Measurement; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; CT, Computed Tomography.

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has underscored the close association between SMI—including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder—and the presence of metabolic disturbances, among them MASLD [14,15]. This association is complex and multifactorial, arising from both intrinsic features of psychiatric disorders and the impact of pharmacological treatments, particularly long-term use of SGAs.

Patients with SMI exhibit a significantly higher prevalence of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, physical inactivity, and unhealthy dietary patterns—factors well recognized in the conventional pathophysiology of MASLD [16]. However, the elevated metabolic risk in this population cannot be fully attributed to these classical factors alone.

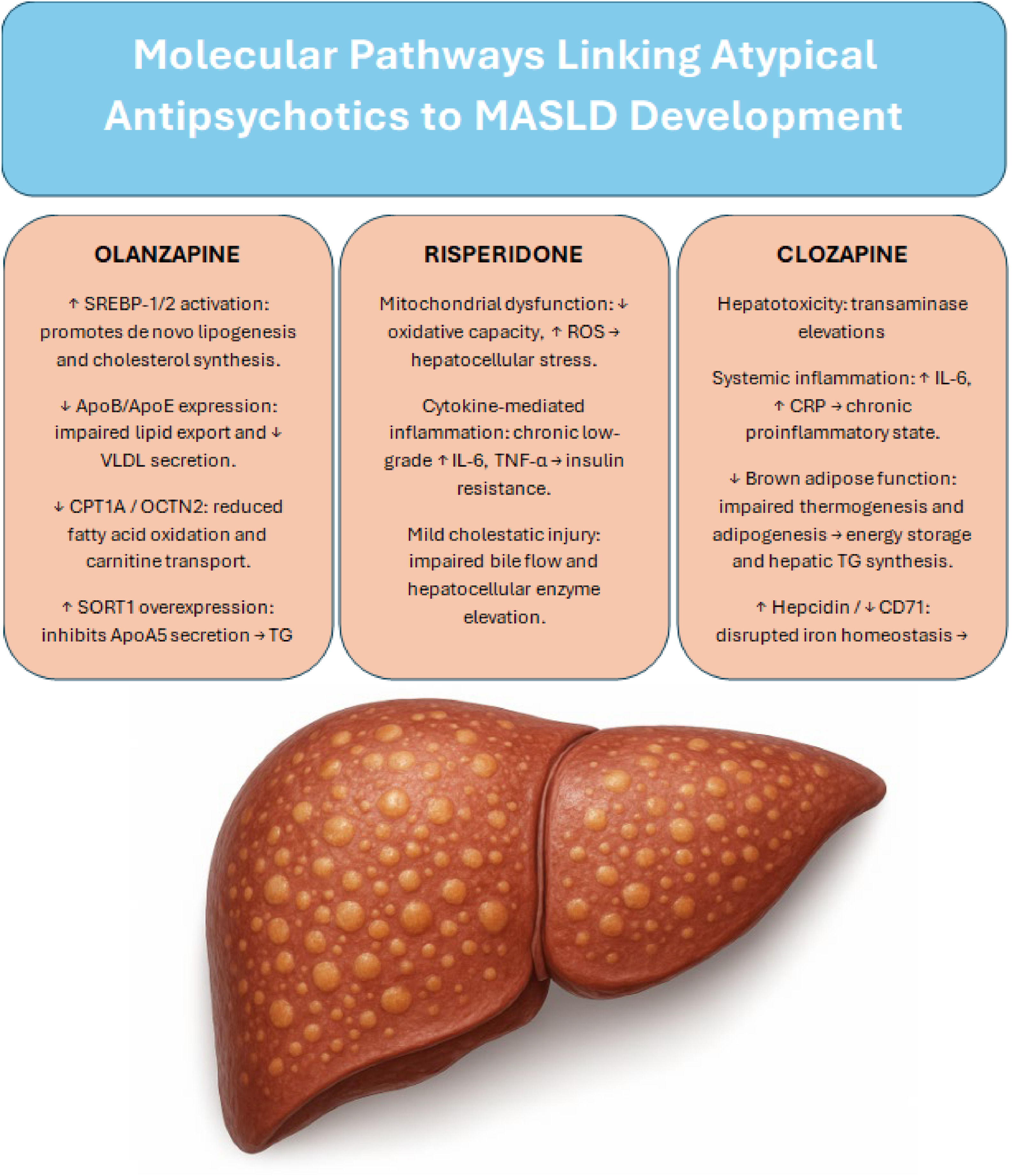

Multiple clinical and experimental studies have demonstrated that SGAs—especially olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone—induce direct molecular alterations in hepatic metabolism. These include inhibition of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, mitochondrial dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, and disturbances in carnitine transport and apolipoprotein synthesis [17–19]. These mechanisms contribute independently and significantly to hepatic steatosis and progression to advanced liver disease in this vulnerable population.

1.4Severe mental illness as a risk factor for MASLDContemporary evidence indicates that patients with severe psychiatric disorders exhibit a markedly reduced life expectancy—estimated between 7 and 20 years—primarily due to medical comorbidities, notably cardiovascular disease. Many of these complications are closely linked to MetS, which is highly prevalent in this population and serves as a critical mediator of increased cardiovascular risk [20,21].

However, the impact of metabolic dysfunction in individuals with SMI extends beyond cardiovascular complications. This dysregulation facilitates abnormal lipid accumulation within hepatocytes, thereby promoting the onset and progression of MASLD. The disease may evolve into more severe forms, such as MASH and eventually cirrhosis [22–24].

Central to this process is the role of SGAs, which, while effective in controlling psychiatric symptoms, are known to exert broad pharmacodynamic actions across multiple receptor systems. These include dopaminergic (primarily D2), serotonergic (5-HT2A/5-HT2C), histaminergic (H1), muscarinic (M3), and adrenergic (α1) receptors. This receptor promiscuity underpins both their therapeutic efficacy and a wide range of adverse metabolic consequences, particularly affecting hepatic function [25].

Among SGAs, olanzapine and clozapine stand out due to their high affinity for H1 and M3 receptors. This contributes to hyperphagia and impaired insulin signaling, mechanisms that synergistically enhance hepatic de novo lipogenesis. Furthermore, genetic polymorphisms in HRH1 and CHRM3 have been associated with increased body mass index (BMI) and elevated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in patients receiving these agents, suggesting a gene–drug interaction that may modulate individual susceptibility to metabolic adverse effects [26].

In parallel, dopaminergic antagonism not only diminishes motivational behaviors such as physical activity but also alters hypothalamic regulatory circuits and circadian rhythms. These changes further impair glucose and lipid metabolism. Notably, animal studies have demonstrated that even low doses of risperidone or olanzapine can induce early hepatic steatosis and proteomic alterations in hepatic and cardiac tissues, independent of significant weight gain [27].

Serotonergic receptor blockade, particularly of 5-HT2A, compounds this effect. Disruption of this pathway has been associated with alterations in energy metabolism and hepatic fibrogenesis. Elevated peripheral serotonin levels—such as those seen in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—can also promote hepatic lipogenesis and interfere with autophagic processes, exacerbating liver injury [28,29].

Taken together, these pharmacological effects establish a strong mechanistic link between SGAs and the development of metabolic disturbances, including obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia—all of which are key drivers of MASLD pathogenesis [30]. This is supported by experimental and clinical evidence suggesting that H1, 5-HT2C, and M3 receptor dysregulation impairs appetite control, insulin dynamics, and energy expenditure [31].

At the hepatic level, these alterations translate into hallmark features of steatotic liver disease such as lipid accumulation, hepatocellular ballooning, and fibrotic remodeling. Importantly, such changes have also been documented in patients with depression, indicating that even non-psychotic affective disorders treated with psychotropic medications may be implicated in liver pathology [32,33].

Finally, a convergence of molecular events—including insulin resistance, persistent low-grade inflammation (e.g., elevated TNF-α and IL-6), mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress—creates a pro-steatogenic hepatic environment. These conditions foster ROS production and subsequent hepatocellular injury. In addition, the serotonin pathway, traditionally considered within the context of neurotransmission, has emerged as a key player in hepatic energy imbalance and fibrogenesis, underscoring the systemic impact of psychotropic modulation [31,35].

1.5Effects of SGAs on hepatic pathophysiology1.5.1ClozapineAmong SGAs, clozapine stands out as one of the agents most strongly associated with hepatotoxicity. Elevated transaminase levels are observed in approximately 15 % to 60 % of patients, often within the first eight weeks of treatment. In some cases, these elevations reach up to three times the upper limit of normal (ULN), potentially necessitating treatment interruption or discontinuation [36].

Beyond hepatic enzyme alterations, clozapine exerts profound metabolic effects that contribute to the development of MASLD. Systemically, it induces a proinflammatory milieu characterized by elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels [37,38]. Simultaneously, it reduces energy expenditure by impairing brown adipose tissue function, specifically through inhibition of adipogenesis and thermogenesis [39,40]. These effects collectively enhance energy storage and promote hepatic triglyceride and VLDL synthesis, fostering the accumulation of lipids within hepatocytes [41].

In addition, clozapine alters iron homeostasis by increasing hepatic hepcidin expression and suppressing the transferrin receptor CD71. These disruptions reduce mitochondrial iron availability, impairing the activity of iron-dependent enzymes such as aconitase and ultimately favoring lipid droplet accumulation [42–45]. This dysregulation of iron metabolism amplifies lipogenic pathways not only in the liver but also in adipose tissue, contributing to systemic metabolic dysfunction and steatosis development [46].

In summary, clozapine exemplifies how SGAs can independently promote MASLD through multiple interrelated mechanisms—ranging from hepatic inflammation and lipogenesis to mitochondrial and micronutrient dysfunction. Its metabolic liabilities underscore the need for proactive monitoring.

1.5.2OlanzapinePreclinical studies have demonstrated that olanzapine-treated animals develop increased visceral adiposity, impaired β-oxidation of fatty acids, and hepatic triglyceride accumulation—key features of MASLD [47]. These effects are partly mediated through central antagonism of H1, 5-HT2C, and M3 receptors, which contribute to hyperphagia and systemic metabolic imbalance [48,49].

At the hepatic level, olanzapine activates sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP-1 and SREBP-2), promoting de novo lipogenesis and altering cholesterol homeostasis [50]. It also disrupts lipid export by downregulating the expression of apolipoproteins ApoB and ApoE, thereby reducing lipoprotein uptake and VLDL secretion [51–54]. Simultaneously, olanzapine impairs fatty acid oxidation by inhibiting carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A) and reducing hepatic carnitine uptake via OCTN2 [18].

A notable pathogenic mechanism involves the upregulation of sortilin (SORT1), a protein that inhibits apolipoprotein A5 (apoA5) secretion and facilitates its intracellular retention, leading to triglyceride accumulation and hepatic steatosis. Experimental SORT1 silencing has been shown to reverse this phenotype, reducing lipid burden and restoring apoA5 export [17,55]. The activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) appears to be a driving force behind SORT1 overexpression, suggesting the existence of an olanzapine–mTORC1–SORT1–apoA5 axis that could represent a novel therapeutic target [56,57].

Furthermore, olanzapine promotes an early lipogenic and proinflammatory phenotype in human adipocytes and adipose-derived stem cells, even at early stages of differentiation. It induces the expression of SREBP-1 and related genes, as well as cytokines linked to chronic low-grade inflammation, which may synergistically exacerbate systemic and hepatic insulin resistance [58–62].

Gene expression profiling in hepatic tissue from olanzapine-treated models also reveals increased expression of fatty acid transporters (CD36, FATP5), activation enzymes (ACSL3, ACSL5), and lipogenic effectors such as DGAT1 and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1). Interestingly, these effects persist even in the context of reduced SREBP-1c and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) levels, suggesting the involvement of non-canonical lipogenic pathways predominantly driven by SCD1 activity [63].

Olanzapine contributes to MASLD pathogenesis through a multifaceted network of central and hepatic mechanisms, including dysregulation of lipid metabolism, suppression of fatty acid oxidation, and proinflammatory remodeling of adipose tissue. The identification of specific molecular targets—such as the SORT1–apoA5 axis—opens the door for potential pharmacological interventions aimed at mitigating olanzapine’s hepatotoxic effects without compromising its antipsychotic efficacy. Fig. 1 shows the main molecular pathways by which antipsychotics contribute to the development of MASLD.

Summary of the main molecular pathways through which major antipsychotics contribute to the development of MASLD

SREBP; sterol regulatory element-binding protein, ApoB; apolipoprotein B, ApoE; apolipoprotein E, VLDL; very-low-density lipoprotein, CPT1A; carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A, OCTN2; Organic Cation/Carnitine Transporter 2, SORT1; Sortilin 1 gene, ApoA5; apolipoprotein A5, TG; Triglycerides, ROS; reactive oxygen specie, IL-6; Interleukin-6, TNF-α; Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha, CRP; C-Reactive Protein, CD71; Cluster of Differentiation 71.

Although to a lesser extent than clozapine or olanzapine, risperidone has also been implicated in hepatic dysfunction, particularly in pediatric populations. Long-term treatment has been associated with elevated liver enzyme levels in up to 52.5 % of children, with approximately 0.8 % of cases exhibiting transaminase elevations exceeding five times the upper limit of normal (ULN) [36].

The underlying mechanisms appear to involve mitochondrial dysfunction, cytokine-mediated low-grade inflammation, and mild cholestatic injury, especially in the context of polypharmacy with other hepatotoxic drugs. Although less severe, these alterations may still contribute to the cumulative hepatic burden in vulnerable patients, particularly when considering long-term exposure and overlapping metabolic risk factors.

2Antipsychotics and steatotic liver injury: underlying molecular mechanismsDrug-induced hepatic steatosis—particularly that associated with antidepressants and antipsychotics—represents a frequent and underrecognized form of hepatotoxicity. It arises from a dysregulation of hepatic lipid homeostasis, driven by an imbalance between lipid uptake and clearance within hepatocytes. Central to this process are mechanisms such as enhanced peripheral lipolysis, increased de novo lipogenesis, inhibition of mitochondrial β-oxidation, and impaired very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion, all of which culminate in lipid accumulation and hepatocellular injury [64].

SGAs have been shown to rapidly reprogram systemic energy metabolism toward lipid dependence, as reflected by decreased levels of circulating free fatty acids and a lowered respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in experimental models [65,66]. Simultaneously, they disrupt the physiological balance between lipolysis and lipogenesis: hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) activity is suppressed, impairing the mobilization of stored fatty acids, while key lipogenic enzymes such as fatty acid synthase (FASN) are upregulated, promoting the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides and adipose tissue hypertrophy [67–69].

These alterations form the pathophysiological core of MASLD in individuals exposed to SGAs. Prolonged treatment with agents such as olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone has been consistently linked to hepatic steatosis and metabolic dysregulation, whereas metabolically neutral antipsychotics, including ziprasidone and aripiprazole, demonstrate a more favorable hepatic safety profile [70].

At the molecular level, antipsychotic-induced activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1 and SREBP-2 pathways, along with upregulation of their downstream targets (e.g., FASN, acetyl-CoA carboxylase [ACC]), drives excessive lipid and cholesterol synthesis [71,72]. In parallel, inhibition of key suppressors of the SCAP/SREBP axis—such as progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1) and insulin-induced gene 2 (INSIG-2)—further sustains lipogenic activity, exacerbating steatosis [73].

Clinically, these molecular disturbances translate into elevated serum levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, and free fatty acids, thus defining the distinctive lipogenic phenotype of MASLD induced by antipsychotic agents. This mechanistic understanding not only reinforces the need for proactive metabolic monitoring in psychiatric populations but also highlights the potential for targeted interventions aimed at modulating lipid pathways, either through pharmacologic agents or lifestyle strategies.

2.1Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in antipsychotic-induced MASLDMitochondrial dysfunction has been identified as a key pathogenic axis in the development of MetS and MASLD induced by SGAs [74–76]. One of the primary mechanisms involves the inhibition of mitochondrial proteins essential for ATP synthesis, thereby impairing cellular energy efficiency. This inhibition is accompanied by a reduction in the availability of substrates for glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), along with increased production of ROS during mitochondrial electron transport [77].

These mitochondrial alterations lead to sustained energy imbalance, insulin resistance, weight gain, and hepatic lipid accumulation. Drugs such as clozapine and olanzapine have been shown to oxidize key energy enzymes — including malate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase, and 3-oxoacid CoA thiolase — directly disrupting the Krebs cycle and reducing the availability of NADH necessary for complex I activity in the respiratory chain [78–82]. Clozapine has also been found to induce mitochondrial swelling and membrane potential loss in cellular models, mirroring findings observed in patients with antipsychotic-induced MetS [81].

Studies have documented significant reductions in mitochondrial respiratory activity dependent on complexes I and II, particularly in cell lines derived from patients with schizophrenia, with olanzapine showing the greatest impact [83]. This mitochondrial susceptibility appears to be modulated by genetic factors as well, such as the 3q29 deletion, which has been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia [84].

SGA-induced mitochondrial toxicity has been widely characterized and includes disruptions in oxidative phosphorylation, decreased ATP production, and increased ROS generation [85–87]. Moreover, alterations in key oxidative metabolism enzymes — such as pyruvate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase — have been described, promoting lipid peroxidation and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, key factors in the progression to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), even in the absence of overt obesity [79,88].

During the progression of MASLD, substantial mitochondrial remodeling occurs, characterized by elevated ROS levels, impaired bioenergetics, and activation of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways — all of which perpetuate hepatic injury [89]. In animal models, SGAs such as olanzapine and risperidone have been shown to disrupt ATP homeostasis, induce lipid peroxidation, and modulate genes involved in apoptosis and autophagy [90,91].

Furthermore, antipsychotics affect the autonomic nervous system through antagonism of α1-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors, impacting hepatic regulation of key processes such as gluconeogenesis, bile secretion, and fibrogenesis [92]. The SGA-induced imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic tone is emerging as a contributing mechanism to hepatic and metabolic dysfunction in this vulnerable population.

2.2Adipocyte dysfunction, hormonal alterations, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)/AMPK signaling2.2.1Lipid storage and adipose tissue dysfunctionSGAs induce significant metabolic disturbances that contribute to hepatic steatosis and systemic adipose tissue dysfunction. In white adipose tissue, these drugs promote lipid accumulation by stimulating the expression of key transcription factors involved in adipocyte differentiation, such as PPAR-γ and C/EBPβ, thereby enhancing adipogenesis. Additionally, AAPs activate the SREBP1c/ADD1 pathway, intensifying de novo lipogenesis and leading to adipocyte hypertrophy—a hallmark of dysfunctional adipose tissue. This environment fosters a pro-inflammatory profile and excessive release of free fatty acids, which further exacerbates insulin resistance and hepatic dysfunction [58,93,94]. This expansion of adipose tissue is not metabolically neutral; it fosters a pro-inflammatory phenotype, characterized by increased release of free fatty acids and cytokines that promote insulin resistance and contribute to hepatic fat deposition. The resulting dysfunctional adipose tissue becomes a critical extrahepatic driver of MASLD.

2.2.2Hormonal alterations in appetite regulationSGAs also interfere with the neurohormonal regulation of energy balance. Histamine H1 receptor antagonism enhances appetite and impairs leptin signaling, diminishing satiety responses [95,96]. Simultaneously, SGAs decrease levels of adiponectin, an adipokine essential for insulin sensitivity and anti-inflammatory signaling, thereby promoting systemic insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction [97–100]. Particularly, olanzapine activates the ghrelin–GHS-R1a axis, stimulating hunger and blunting satiety responses, which contributes to hyperphagia and positive energy balance [101–103]. These hormonal changes synergize with adipose dysfunction to amplify metabolic injury.

2.2.3AhR and metabolic dysfunctionMore recently, AhR activation has emerged as a central mechanism linking SGAs to hepatic and systemic metabolic dysfunction. Triggered by inflammatory signals and metabolic stress, AhR activation leads to inhibition of AMPK, suppression of Glut4 expression, and impaired mitophagy, all of which exacerbate insulin resistance and hepatocellular energy imbalance [104–106]. AhR also reduces hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) production, a gasotransmitter with known antidiabetic and cytoprotective properties, thereby promoting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Further compounding these effects, AhR stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which shifts cellular metabolism toward anaerobic glycolysis and increases glucose dependency, intensifying the metabolic burden on hepatocytes [107].

In summary, SGAs contribute to MASLD not only through direct hepatic mechanisms but also via systemic pathways involving adipose tissue dysfunction, altered hormonal regulation of appetite, and disruption of the AhR/AMPK signaling axis. These mechanisms act in concert to amplify lipotoxicity, insulin resistance, and mitochondrial stress, underscoring the need for mechanistically targeted strategies to mitigate the metabolic side effects of antipsychotic therapy.

2.2.4AMPK pathway disruption: central and peripheral effectsAMPK functions as a master energy sensor regulating metabolism across multiple tissues. In the central nervous system—particularly the hypothalamus and cortex—SGAs such as olanzapine and clozapine have been shown to increase AMPK phosphorylation, which reduces energy expenditure and promotes hyperphagia [108–111].

In contrast, the effects of SGAs on AMPK activity in peripheral tissues like the liver and adipose tissue are inconsistent. Some studies report AMPK activation, while others describe its inhibition. This variability disrupts critical processes such as fatty acid oxidation and glucose uptake, fostering insulin resistance and hepatic triglyceride accumulation [17,112–114]. This energetic imbalance reinforces the progression of MASLD in patients chronically treated with SGAs.

2.3Glucose transport alterations and dyslipidemia: role of apoA5, sortilin, and PCSK9SGAs disrupt glucose metabolism through multiple mechanisms, beginning with direct inhibition of glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3, as demonstrated in PC12 neuronal cell models [115–118]. This effect is compounded in peripheral tissues—such as adipocytes and skeletal muscle—where SGAs interfere with GLUT4 trafficking, a process regulated by the PKB/Akt signaling pathway. Specifically, disruption of the β-arrestin 2/PP2A/Akt complex impairs insulin signaling, reducing glucose uptake and promoting compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which over time progresses to insulin resistance and chronic hyperglycemia—hallmarks of MASLD pathophysiology [119–121].

2.3.1Dyslipidemia and apoA5/sortilin dysregulationDyslipidemia is another frequent consequence of antipsychotic treatment. SGAs—especially olanzapine and clozapine—are strongly associated with elevated fasting and postprandial triglycerides, as evidenced by phase 1 of the CATIE trial, where olanzapine and quetiapine led to significant increases, while ziprasidone showed a neutral profile, and risperidone and perphenazine were associated with reduced triglyceride levels [70]. These lipid alterations appear to be drug-specific and reversible, as shown by acute changes following drug initiation or discontinuation. A potential explanation involves the action of an unknown “receptor X”, thought to mediate effects across liver, adipose tissue, muscle, and the CNS [122]. Dysregulation of apoA5 and sortilin pathways has also been implicated, especially in the context of olanzapine, where intracellular retention of apoA5 contributes to steatosis.

The expansion and dysfunction of adipose tissue in response to SGAs fosters a pro-inflammatory milieu, with increased infiltration of M1 macrophages and elevated secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [123–125]. Among SGAs, clozapine has shown the strongest association with systemic inflammation, reflected in increased levels of IL-6 and CRP in patients with schizophrenia [126]. This persistent low-grade inflammation exacerbates hepatic insulin resistance and promotes progression from simple steatosis to NASH, eventually favoring fibrosis development.

SGAs contribute to MASLD through interconnected mechanisms involving impaired glucose transport, dysregulated lipid handling, and chronic inflammation. These processes act synergistically to disrupt systemic and hepatic metabolic homeostasis. Future research should focus on delineating drug-specific pathways, identifying protective molecular targets (e.g., apoA5 modulation, receptor X blockade), and developing clinical strategies to mitigate the metabolic burden of antipsychotic therapy—particularly in patients at high risk for steatotic liver disease.

2.4Experimental evidence and molecular mechanismsMultiple experimental studies have demonstrated that SGAs can induce metabolic and hepatic dysfunction even in the absence of psychiatric comorbidities or obesogenic diets.

In murine models, clozapine impaired hepatic metabolism by inhibiting the renal carnitine transporter (OCTN2), leading to systemic l-carnitine deficiency. This disruption compromised mitochondrial β-oxidation and promoted hepatic accumulation of triglycerides and cholesterol. Supplementation with l-carnitine partially reversed these effects, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for patients treated with clozapine [18].

Similarly, histological studies in rats have shown that both olanzapine and aripiprazole induce hepatic structural damage consistent with steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, inflammatory infiltrates, and varying degrees of fibrosis. While olanzapine caused more severe injury, aripiprazole also produced notable hepatic changes, indicating that even antipsychotics with a lower metabolic risk may contribute to liver injury [127].

The role of the gut microbiota has also been explored. In fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiments, microbial communities from individuals resistant to olanzapine-induced steatosis conferred hepatoprotection to recipient rats. This effect was characterized by lower transaminases, reduced hepatic lipid content, downregulation of lipogenic genes, and enhanced β-oxidation via increased Cpt1a and Fgf21 expression. The protective microbiota produced higher levels of butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that modulates hepatic leptin signaling and suppresses lipogenesis [128].

In models of diet-induced obesity, risperidone exacerbated weight gain, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, and hepatic injury. This was associated with upregulation of lipogenic and inflammatory genes including SREBP1, FASN, FABP4, and PNPLA3, alongside renal oxidative stress, reflecting a broader multiorgan impact in metabolically predisposed individuals [129].

Even under a standard diet, both risperidone and olanzapine have been shown to induce significant liver injury accompanied by proteomic reprogramming. These changes affected key pathways including glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, lipogenesis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Risperidone activated mitogenic signaling and PPAR pathways, while olanzapine suppressed glycolytic enzymes and mitochondrial biogenesis. Both agents also disrupted autonomic nervous system signaling, notably increasing sympathetic tone, which impairs hepatic energy metabolism, bile secretion, and regenerative processes [22].

Taken together, experimental studies suggest that SGAs can contribute to the development or exacerbation of MASLD through interconnected mechanisms such as mitochondrial dysfunction, enhanced lipogenesis, systemic inflammation, gut microbiota alterations, and autonomic nervous system imbalance. While these models offer valuable mechanistic insights, further translational research is needed to clarify the relative contribution of each pathway in humans and to identify modifiable factors that could mitigate hepatic injury in this context.

2.5Gut–liver–brain axis and intestinal dysbiosisThe pathogenesis of MASLD in patients with psychiatric disorders is increasingly understood through the lens of a “multiple-hit” model. This framework proposes that genetic, neuroendocrine, inflammatory, and environmental factors converge to promote hepatic steatosis and its progression. Among these, chronic dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis plays a central role. Frequently observed in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder, sustained HPA activation leads to cortisol overproduction, which in turn promotes insulin resistance, visceral adiposity, and low-grade systemic inflammation—key drivers of MASLD development [130–132].

This neuroendocrine imbalance not only accelerates triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes but also triggers activation of Kupffer cells and a proinflammatory hepatic milieu, facilitating the transition from simple steatosis to MASH [20,22,133].

Finally, the gut–brain axis is increasingly recognized as a contributor to antipsychotic-induced metabolic derangements. Intestinal dysbiosis triggered by SGAs has been associated with elevated production of kynurenine, a tryptophan metabolite that activates the AhR. AhR signaling promotes systemic and hepatic inflammation, disrupts energy metabolism, and contributes to the hepatic injury observed in MASLD [134,135].

The gut–liver–brain axis provides a unifying framework that links psychiatric illness, antipsychotic treatment, and hepatic steatosis. Disruption at multiple levels—including neuroendocrine signaling, autonomic regulation, adipose tissue homeostasis, and intestinal microbiota—creates a permissive environment for MASLD development and progression. This integrative model highlights novel targets for therapeutic intervention and underscores the need for a multidisciplinary approach to managing metabolic health in patients with SMI.

2.6Intestinal dysbiosis and omega-3 fatty acidsProlonged exposure to SGAs has been associated with significant depletion of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in both hepatic and plasma compartments [136–138]. These essential fatty acids are critical for maintaining membrane fluidity, regulating inflammatory responses, and supporting overall metabolic homeostasis. Their reduction not only compromises cellular membrane integrity but also amplifies systemic inflammation, contributing to the metabolic dysfunction characteristic of MASLD.

Concurrently, SGAs induce significant alterations in gut microbiota composition, reducing microbial diversity and promoting overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria, particularly within the Enterobacteriaceae family. This dysbiosis increases intestinal permeability and facilitates translocation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into systemic circulation, triggering endotoxemia. Circulating LPS activates proinflammatory hepatic signaling pathways, further exacerbating lipid accumulation, promoting fibrogenesis, and accelerating the transition from MASLD to MASH [139].

Taken together, omega-3 fatty acid depletion and antipsychotic-induced dysbiosis represent two interrelated mechanisms that intensify hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Their identification as modifiable factors opens avenues for preventive strategies—such as dietary interventions and microbiota modulation—that may mitigate MASLD progression in patients undergoing long-term SGA therapy.

2.7Genetic and epigenetic factors: PNPLA3, mitochondrial dysfunction, and microRNAsThe rs738409 (I148M) polymorphism in the PNPLA3 gene has emerged as a key genetic determinant of hepatic triglyceride accumulation and fibrosis progression in MASLD. In addition to its hepatic role, emerging evidence suggests PNPLA3 may influence central energy homeostasis, potentially linking metabolic susceptibility to the adverse effects of antipsychotics. Similarly, variants in TM6SF2 (rs58542926) and MBOAT7 (rs641738) have been associated with increased risk of steatosis and liver fibrosis, via impaired VLDL secretion and altered phospholipid remodeling, respectively [140].

Although direct evidence of interactions between SGAs and these specific gene variants is currently limited, preclinical and pharmacogenomic studies suggest that antipsychotic-induced hepatic injury may be amplified in genetically susceptible individuals. In this context, the combined presence of PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and MBOAT7 risk alleles may lower the threshold for antipsychotic-induced steatosis or progression to MASH. These genes represent a shared axis of hepatic vulnerability, whose expression and impact could be modulated by neuroendocrine alterations associated with psychiatric illness and psychotropic treatment.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are key factors in the transition from NAFLD to NASH. Within this framework, chronic low-grade inflammation serves as a shared pathogenic link between MASLD and psychiatric disorders. Inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6 not only promote hepatic metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance but are also implicated in the pathophysiology of affective and cognitive disturbances observed in mood disorders [34,141–143].

In addition, intestinal dysbiosis—frequently observed in patients treated with antipsychotics—can trigger multiple mechanisms that contribute to steatosis, including increased monosaccharide absorption, endotoxin production, and activation of hepatic inflammatory pathways. These microbial imbalances are also associated with alterations in the gut–brain axis, implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental and affective disorders [144,145].

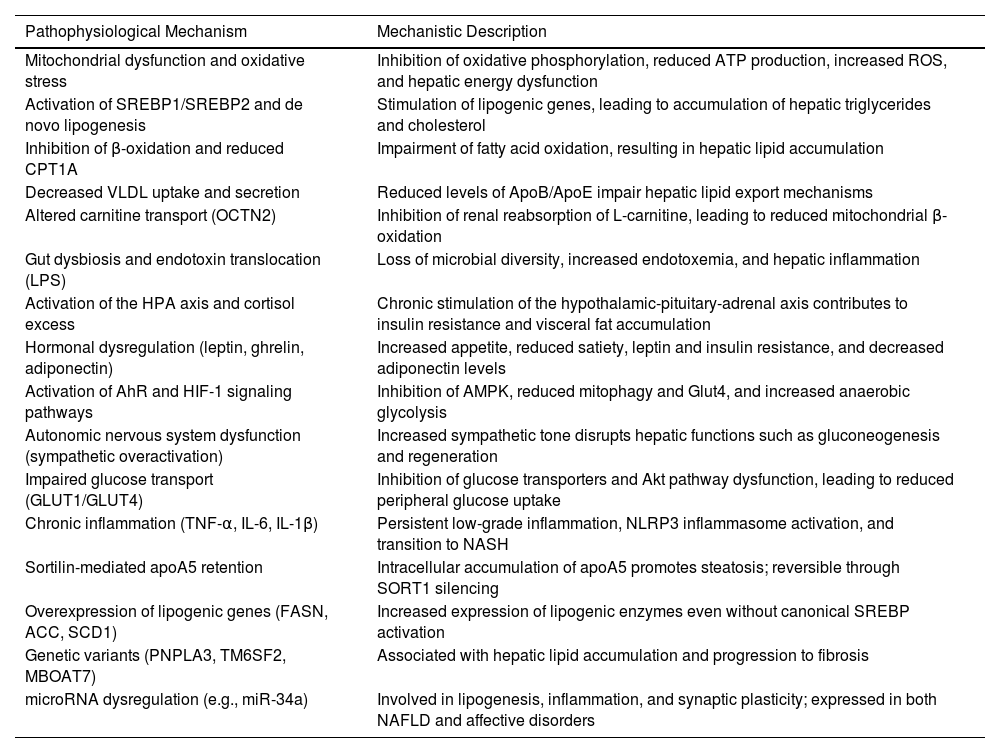

Finally, miRNA-mediated epigenetic regulation—particularly by miR-34a—represents a point of convergence between hepatic and neuropsychiatric abnormalities. This molecule regulates key functions such as lipogenesis, inflammation, and synaptic plasticity, and its overexpression has been observed in MASLD models and various psychiatric conditions, positioning it as a potential shared biomarker and therapeutic target [146,147]. Table 2 shows the different pathophysiological mechanisms associated with antipsychotic-induced MASLD.

Pathophysiological mechanisms associated with antipsychotic-induced MASLD.

SREBP1/SREBP2; sterol regulatory element-binding protein, CPT1A; carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A, OCTN2; Organic Cation/Carnitine Transporter 2, VLDL; very-low-density lipoprotein, LPS; lipopolysaccharide, AhR; aryl hydrocarbon receptor, HIF-1; Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1, GLUT; Glucose Transporter, apoA5; apolipoprotein A5, TNF-α; Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha, L-6; Interleukin-6, IL-1β; Interleukin-1 bet, FASN; Fatty Acid Synthase, ACC; Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase, SCD1; stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1, PNPLA3; Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3, TM6SF2; Transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2, MBOAT7; Membrane Bound O-Acyltransferase Domain-containing 7, miR-34a; microRNA-34a, ATP; Adenosine Triphosphate, ROS; reactive oxygen species, Apo; Apolipoprotein, AMPK; AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt; Protein Kinase B, NLRP3; NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3, NASH; non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, SORT1; Sortilin 1 gene.

Given the metabolic risk associated with SGAs, it is essential to implement systematic clinical monitoring in patients undergoing such treatment. Periodic evaluations are recommended, including measurements of body weight, waist circumference, lipid profile, fasting glucose, and liver function tests, to detect early signs of metabolic dysfunction or incipient liver damage [148]. This surveillance is particularly relevant in the current context of a global rise in the prevalence of MASLD, which may progress asymptomatically to advanced stages such as MASH, hepatic fibrosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

In this regard, the use of non-invasive tools for the early detection of MASLD in psychiatric populations has been proposed as an effective strategy. Indicators such as the FLI with values ≥60 and the FIB-4 index have shown utility as screening methods in psychiatric clinical settings, allowing the identification of patients at high risk of liver damage [5].

However, the diagnosis of MASLD in individuals with SMI remains a challenge. Limitations include underdiagnosis, limited access to healthcare services, and low clinical suspicion in this population. Although non-invasive techniques such as the Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP), transient elastography (VCTE), and serum biomarkers are available, validated diagnostic algorithms specifically designed for patients with psychiatric disorders have not yet been established [149]. These gaps highlight the need to adapt and validate liver assessment tools for effective application in mental health contexts.

4Limitations of the current evidenceDespite growing recognition of the relationship between SGA use and MASLD, important limitations remain in the available evidence. Most studies to date are cross-sectional, observational, or preclinical in nature, which hinders the establishment of strong causal relationships. In particular, there is a marked scarcity of controlled longitudinal studies specifically designed to evaluate the incidence, progression, and reversibility of MASLD in psychiatric populations chronically exposed to SGAs.

Moreover, no unified consensus exists regarding the optimal criteria for diagnosing and screening MASLD in patients with SMI, limiting study comparability and hampering the implementation of standardized clinical protocols. This lack of methodological uniformity underscores the need for robust evidence generated through prospective cohorts and clinical trials with clearly defined diagnostic parameters that integrate metabolic, hepatic, and psychiatric variables into their analyses.

5ConclusionsThe accumulating evidence demonstrates that MASLD should be recognized as a critical comorbidity in patients with psychiatric disorders, particularly those undergoing treatment with SGAs. Its high prevalence, silent nature, and potential progression to advanced forms such as MASH, hepatic fibrosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma represent an emerging challenge for public health and interdisciplinary clinical practice.

In light of this scenario, it is urgent to establish systematic screening strategies, active metabolic monitoring, and timely referral to gastroenterology in cases of persistent abnormalities. Additionally, there is an imperative need to promote new lines of research focused on adjunctive metabolic therapies that can mitigate hepatic risk without compromising psychiatric stability. This includes the study of agents that modulate the AMPK pathway, the gut microbiota, or restore lipid balance and mitochondrial function. The development of comprehensive, personalized, and safe therapeutic approaches represents a key step toward preventing liver damage and improving the overall prognosis in this vulnerable population.

Author contributionsConceptualization, C.G., M.U. and N.C.-T.; methodology, C.G. and M.U.; validation, C.G., M.U. and N.C.-T.; formal analysis, C.G., M.U. and N.C.-T.; investigation, C.G. and M.U.; resources, C.G., M.U. and N.C.-T.; data curation, C.G., M.U. and N.C.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G. and M.U.; writing—review and editing, C.G., M.U. and N.C.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.