Most epidemiological data on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) originate from resource-rich countries. We have previously described the epidemiology of HCC in South America through the South American Liver Research Network. Here, we provide an update on the changing epidemiology of HCC in the continent seven years since that report.

Materials and MethodsWe evaluated all cases of HCC diagnosed between 2019 to 2021 in centers from six countries in South America. A templated, retrospective chart review of patient characteristics at the time of HCC diagnosis, including basic demographic, clinical and laboratory data, was completed. Diagnosis of HCC was made radiologically or histologically for all cases via institutional standards.

ResultsCenters contributed to a total of 339 HCC cases. Peru accounted for 37% (n=125) of patients; Brazil 16% (n=57); Chile 15% (n=51); Colombia 14% (n=48); Argentina 9% (n=29); and Ecuador 9% (n=29). The median age at HCC diagnosis was 67 years (IQR 59-73) and 61% were male. The most common risk factor was nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, 37%), followed by hepatitis C (17%), alcohol use disorder (11%) and hepatitis B (12%). The majority of HCCs occurred in the setting of cirrhosis (80%). HBV-related HCC occurred at a younger age compared to other causes, with a median age of 46 years (IQR 36-64).

ConclusionsWe report dramatic changes in the epidemiology of HCC in South America over the last decade, with a substantial increase in NAFLD-related HCC. HBV-related HCC still occurs at a much younger age when compared to other causes.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is becoming the fifth most common cancer in men and the second overall cause of cancer-related death worldwide, accounting for 746,000 deaths a year [1]. The majority of HCCs occur in the setting of underlying cirrhosis. Therefore, the global epidemiology of HCC is determined by the prevalence of specific underlying liver diseases in different regions [2]. Most epidemiological data on HCC originate from resource-rich countries. Indeed, the largest worldwide study to date assessing HCC epidemiology provides no information from Africa or South America [3]. Through the South American Liver Research Network (SALRN), we previously described the epidemiology of HCC in South America. In that study, we evaluated 1336 HCC patients seen between 2006 and 2014 at 14 centers in six South American countries using a retrospective study design with participating centers completing a template chart of patient characteristics. We found then that the median age of HCC diagnosis was 64 years and the most common etiology for HCC was hepatitis C infection, followed by alcoholic liver disease [4].

Over the last 10 years, there has been a dramatic change in the perceived epidemiology of HCC with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) rising in frequency as an underlying cause [5–7]. Here we provide an update on the changing epidemiology of HCC in the South American continent over the last decade, utilizing data from a cohort of patients diagnosed with HCC between 2019-2021, with participating centers in Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Chile.

2Material and Methods2.1General methodologyThis is a retrospective cohort study aimed at identifying the demographics and risk factors associated with a new diagnosis of HCC in South America. A concerted effort was made to identify characteristics of HCC at the time of diagnosis. Overall, six academic medical centers from six countries in South America participated, providing information on 339 patients diagnosed with HCC between January 2019 and January 2021. The main objective was to assess the epidemiology of HCC with a focus on risk factors, age and gender differences, as well as clinical outcomes. Secondary objectives were the evaluation of therapies offered and the rate of survival based on the presence of multiple variables.

Participating centers completed a standardized chart review and in-depth evaluation of patient characteristics at the time of HCC diagnosis based on a predeveloped set of questions. Data was entered into Redcap - a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases.

2.2Clinical variablesDiagnosis of HCC in all cases was made radiologically or histologically as defined by institutional standards. Radiologically diagnosed cases were made in accordance with guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) or the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) [8,9]. Variables studied included age, gender, chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV), presence of alcohol use disorder, evidence of NAFLD spectrum or cryptogenic cirrhosis, and evidence of other underlying liver diseases. Some (but not all) centers provided data on alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels at the time of diagnosis. NAFLD diagnosis was defined by the primary hepatologist but requested to clarify if noted on imaging or biopsy. In this regard, description of steatosis in the liver by imaging or presence of >5% fat on liver biopsy in individuals with ≤1 drink a day were considered NAFLD. This stratification was conveyed to the investigators before entering data in the database (regardless, the retrospective nature of the study should be taken into account for this point).

Diagnosis of HCC under surveillance program in each center was defined as a diagnosis of HCC being made while a patient was undergoing systematic screening for HCC with semiannual ultrasound.

2.3Ethical statementEthical approval was obtained by each participating center and by Hennepin Healthcare (HSR #17-4344).

3Results3.1General demographicsBetween 2019 and 2021, centers from six countries across South America contributed data for an aggregate of 339 patients with a new diagnosis of HCC. Peru accounted for 37% (n = 125) of patients; Brazil 16% (n = 57); Chile, 15% (n =51); Colombia, 14% (n = 48); Argentina, 9% (n = 29); and Ecuador, 9% (n = 29). Of the 339 patients, 61% were male and 39% female. The median age of diagnosis was 67 years (IQR 59-73). The median age at the time of diagnosis differed by country – with the youngest median being from Argentina at 63 years (IQR 56-68) and the oldest being from Colombia with a median age of 69 years (IQR 63-77). Peru, Ecuador, Chile and Brazil had median ages of 66 (IQR 56-73), 69 (IQR 59-73), 68 (IQR 63-75), and 65 years (IQR 58-68), respectively. HCC related to HBV showed a much younger age of diagnosis at a median age of 46 years (IQR 36-64).

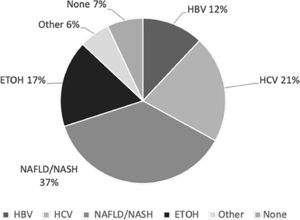

The most common risk factors for HCC were NAFLD/NASH (37%), HCV (21%), HBV infection (12%) and alcoholic liver disease (17%) (Fig. 1). Nineteen percent of HCV-infected patients (n=14) and 2% of HBV-infected patients (n=1) also had alcohol consumption as a second risk factor for HCC.

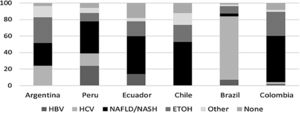

The distribution of risk factors for HCC was relatively heterogeneous throughout the countries, with NAFLD being the most common risk factor for HCC in all countries except for Brazil. NAFLD as the cause of HCC constituted 28% of cases in Argentina, 39% in Peru, 46% in Ecuador, 53% in Chile, 56% in Colombia and 4 % in Brazil. (Fig. 2)

3.2Tumor characteristicsTwenty percent of patients developed HCC in the absence of cirrhosis. Peru had the highest percentage of non-cirrhotic HCCs (31%), followed by Ecuador (28%), Chile (26%), Brazil (12%), Argentina (7%) and Colombia (4%). The most common causes of non-cirrhotic HCC in the entire cohort were HBV (31%) and NAFLD (28%). The median age of HCC in non-cirrhotic patients was 61 years (IQR 42-72).

Most tumors (84%) were diagnosed radiologically, while 16% were diagnosed through biopsy. A larger group of HCC diagnoses were made after patients presented with symptoms (57%), while 144 patients (43%) were detected under HCC surveillance. The cancer stage at the time of diagnosis using Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) criteria was also heterogeneously distributed, with BCLC stage A being the most frequent (43%), followed by stage B (33%), and stages C and D (13%,11% respectively).

The median tumor size in the entire group was 5 cm (IQR 2.9-9). In addition, the size of the tumor differed depending on the underlying liver disease - with 9 cm (IQR 4.5-14) in those with HBV, 5.8 cm (IQR 3.2-9.4) in alcohol-related HCC, 5 cm (IQR 2.85-8) in NAFLD/NASH patients, and 3.5 cm (2.3-5.45) in those with HCV.

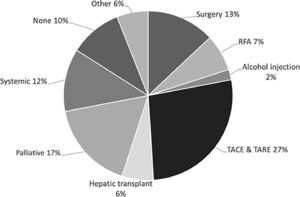

3.3Treatment and survivalTreatment data were available in 334 (98.5%) of the patients in our cohort. Specific treatment modalities for each country varied and are described in Fig. 3. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or Transarterial radio-embolization (TARE) were the most commonly used first therapeutic approach (27%). A total of 28% of patients underwent treatment with curative intent, using either radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (7%), liver transplantation (6%), resection (13%) and percutaneous alcohol injection (2%). Systemic treatment constituted 11%. Eleven percent of patients were not offered any specific treatment for HCC.

Finally, most patients (52%) were no longer alive at the time of data entry. When assessed by etiology, 48% of those with underlying NAFLD had died, while 60% of those with HBV-related HCC had died.

4DiscussionOur study provides an updated assessment of risk factors, demographics, surveillance data, and therapeutic modalities offered for HCC in South America. In our initial study, chronic infection with HCV was found to be the most common underlying liver disease in patients diagnosed with HCC [4]. In this study, from 2019 to 2021, we found that NAFLD has become the most common etiology of liver disease in HCC patients. The percentage of NAFLD-HCC showed a dramatic rise and quadrupled compared to our initial published study (9% vs. 37%) [4]. This finding adds significant information to the scarce but growing epidemiological data on HCC in this continent and correlates with the rise of NAFLD across the globe seen in other parts of the world [10,11].

As a result of the obesity pandemic, NAFLD is rising in the United States and Europe and rapidly becoming one of the most common reasons for liver transplantation and liver-related mortality [12]. The incidence of NAFLD-HCC is also rising in the United States, estimated to be increasing by a rate of 9% annually [13,14]. This rising trend was apparent in our cohort as well. In addition, the presence of diabetes mellitus was found in a high number of the patients with NAFLD-HCC (57%), again corroborating the notion that several risk factors, including the presence of diabetes which has been shown to have a higher prevalence in those with NAFLD-NASH and advanced disease, may possibly hasten the progression of NAFLD to cirrhosis and HCC [15,16]. As in every multicentric study, there is the inherent risk that the contribution of cases from one center could bias the sample. However, in our study, with the exception of Brazil, most centers showed a relatively uniform proportion of NAFLD-related HCC.

Although cirrhosis is present in most cases of HCC, liver cancer has been known to occur in patients without cirrhosis [12,17]. HBV, due to its direct carcinogenic effect, can lead to the development of HCC in the absence of advanced fibrosis [18]. More recently, NAFLD has been documented to be associated with HCC in patients without cirrhosis. One study from the United States, utilizing data from the Veteran's Administration, documented that 13% of those with HCC did not have cirrhosis [19]. These phenomena were not only apparent in our study but also surprising in their degree, with the most common cases of non-cirrhotic HCC found in those with HBV and NAFLD and a total of the non-cirrhotic cases exceeding 15% in several countries.

The morbidity and mortality of HCC are largely dependent on the timing of diagnosis [17,20,21]. More than half of the patients in our study were diagnosed after presenting with symptoms that necessitated evaluation, subsequently leading to the diagnosis of HCC, in comparison to 43% of the patients diagnosed under surveillance. This may explain the larger proportion of patients in later stages of the disease (such as those with BCLC stage B-D, which made up 57%) and the median size of HCC being 5 cm. This late diagnosis of HCC limits the treatment options available to these patients [9]. Interestingly, the proportion of patients diagnosed via surveillance was strikingly similar to that found in our previous study (42% and 47%, respectively), highlighting the persistent need for improvement in surveillance implementation in the region. In our cohort of patients, only a small proportion of patients underwent treatment with curative intent (28%), despite 40% being diagnosed with BCLC stage A. This wide disparity in the available treatment options related to the stage of diagnosis was also apparent in our initial study [4]. It is likely that TACE is used frequently in BCLA A patients in the region (personal communications). Surgical modalities such as resection and liver transplantation (which also serve a second purpose of treating the underlying liver disease) are only feasible in early cases of HCC, and these were employed in 19% of cases [22]. Palliative care and systemic treatment, on the other hand, were utilized in 28% of cases. Fostering a robust HCC surveillance program is imperative in the push for early detection of HCC, and this will, in turn, expand the options of treatment available to these patients. Interestingly, the use of systemic therapy was only present in 11% of patients in our current study, compared to 16% in our previous study. This was a surprising finding as there has recently been a much wider array of systemic therapies beyond sorafenib, the only available therapy at the time of the first study. This is an area that will require further investigation.

HBV-related HCC was shown to occur at younger ages compared to the other etiological factors. Our group had previously shown that nearly 40% of patients with HBV-HCC occurred before the age of 50 [23]. Moreover, in this new cohort of patients, the median size of HCC in HBV patients was 9 cm (compared to the overall median size of 5 cm); furthermore, the mortality rate was 60% in HBV-HCC patients (compared to the overall mortality of 52%). It is plausible that the poor outcomes of HBV-HCC patients are related to late diagnosis and lack of surveillance, especially in those who do not have cirrhosis. These findings suggest a consideration of early screening in South American non-cirrhotic patients with HBV as it is recommended in patients of African and Asian origin [9].

One limitation of our study is the smaller number of patients compared to our previous report and so this may not necessarily be representative of the entire population in South America. Also, the retrospective nature of the study may reduce the validity of some of the information obtained, particularly as there could be some variation in imaging used for diagnosis across centers, though this limitation was mitigated by creating a standardized preset template of information to be collected from each patient diagnosed with HCC to increase validity.

5ConclusionsIn summary, our study updates the literature on the epidemiology of HCC in South America. The rate of NAFLD-related HCC is rising in tandem with the rest of the world. Late diagnosis remains problematic and may be responsible for the low rate of utilization of curative modalities for the treatment of HCC. Increased deployment of HCC surveillance programs will probably play a major role in reducing the morbidity and mortality of HCC in South America.