Introduction and aim. The inability to distinguish cancer (CSCs) from normal stem cells (NSCs) has hindered attempts to identify safer, more effective therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The aim of this study was to document and compare cell membrane potential differences (PDs) of CSCs and NSCs derived from human HCC and healthy livers respectively and determine whether altered GABAergic innervation could explain the differences.

Material and methods. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) positive stem cells were isolated from human liver tissues by magnetic bead separations. Cellular PDs were recorded by microelectrode impalement of freshly isolated cells. GABAA receptor subunit expression was documented by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunofluorescence.

Results. CSCs were significantly depolarized (-7.0 ± 1.3 mV) relative to NSCs (-23.0 ± 1.4 mV, p < 0.01). The depolarized state was associated with different GABAA receptor subunit expression profiles wherein phasic transmission, represented by GAGAAa3 subunit expression, was prevalent in CSCs while tonic transmission, represented by GABAAa6 subunit expression, prevailed in NSCs. In addition, GABAA subunits a3, |33, y3 and S were strongly expressed in CSCs while GABAAn expression was dominant in NSCs. CSCs and NSCs responded similarly to GABAA receptor agonists (APD: 12.5 ± 1.2 mV and 11.0 ± 3.5 mV respectively).

Conclusion. The results of this study indicate that CSCs are significantly depolarized relative to NSCs and these differences are associated with differences in GABAA receptor subunit expression. Together they provide new insights into the pathogenesis and possible treatment of human HCC.

Cancer stem cells (CSC) are a malignant subpopulation of cells within a tumor that have the ability to self-replicate, differentiate into different cell lineages and resist chemotherapy.1 They have been identified in many solid organ tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although uncertainty remains regarding the precise role these cells play in the pathogenesis of cancer, recent data suggest they contribute to tumor development, growth, invasion and metastases.1 As a result, CSCs have emerged as an important, albeit elusive therapeutic target.2

One of the principal challenges in developing safe and effective means of eradicating CSCs from tumor tissues is the difficulty in distinguishing CSCs from normal stem cells (NSCs) present in adjacent non-tumor tissue.3 This problem is compounded in the liver where attempts to eradicate CSCs from HCC often occur in the setting of cirrhosis where NSCs are required to maintain hepato-cyte populations and thereby, essential liver functions.4

Recently, our laboratory identified potentially important distinctions between CSCs and NSCs that could serve as the basis for new therapeutic strategies for HCC.5 Specifically, we documented that CSCs derived from the human Huh-7 and PLC malignant hepatocyte cell lines have significantly depolarized (less negatively charged) resting cell membrane potential differences (PD) when compared to the non-malignant, murine WBF-344 NSC cell line.5 Whether these differences exist in CSCs and NSCs derived from human liver tissues remains to be determined.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a potent inhibitory neurotransmitter that plays an important role in embryogenesis and tissue development by regulating stem cell activity and differentiation.6,7 GABAA receptors are heterooligomeric, ligand-gated ion channels consisting of 16 subunits, commonly present in a pentameric configura-tion.8 In non-synaptic cells (such as hepatocytes) GABAergic activity is influenced by those subunits responsible for “tonic” transmission (resulting in prolonged hyperpolarization) of which α6 is considered the prototype, whereas in synaptic cells (such as neurons), “phasic” transmission, related to the presence of the α3 subunit, is dominant.9

In the present study, we documented the PDs of primary CSCs and NSCs derived from freshly isolated HCC and adjacent non-tumor tissues respectively. We also documented the expression of various GABAA receptor subu-nits including α3 and α6 in the two cell populations and the PD responses of CSCs and NSCs to GABAA receptor agonists.

Material and MethodsStem cell isolationsStem cell isolations (both CSCs and NSCs) were performed as described by Kahan, et al.10 Briefly, tumor or adjacent non-tumor tissues were dissected and digested in 1 μg/mL of type 4 collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ont., Canada) solution at 37°C for 15 to 30 min. Contaminated red blood cells were lysed with ammonium chloride solution (STEM-CELL Technologies, Burlington, Ont., Canada) on ice for 5 min. CD45+ leukocytes and Annexin V+ apoptotic cells were removed by an autoM-ACS-pro cell separator and magnet beads (Miltenyi Bio-tec, San Diego, CA, USA). EpCAM-positive and -negative cells were further enriched by an autoMACS-pro cell separator and CD326 (EpCAM) MicroBeads (Miltenyi Bio-tec). All isolations and experiments were performed on 3-6 separate occasions.

Membrane potential determinations (PDs)Resting voltage membrane PDs were measured using intracellular microelectrodes as previously described.11 Single-barreled microelectrodes were drawn on a horizontal puller (Brown-Flaming micropipette puller, model P-87; Sutter Instruments, Novato, California, USA) from Omega-Dot borosilicate tubing [1.0 mm (outer diameter), 0.5 mm (inner diameter)]; (Sutter Instruments), filled with 0.5 mol/L potassium chloride and beveled to a 30° angle to a tip resistance of approximately 100 MΩ. Electrical signals were conducted via an Ag-AgCl electrode connected to an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, Calif.). Data acquisition was controlled by interfacing the amplifier to a Digidata acquisition card (Axon Instruments) and using the Axoscope software (version 7.0; Axon Instruments). Junction potential was accounted for using JPCalc (version 2.2; University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia). Criteria for acceptable impalements included an abrupt negative deflection on penetration of the cell, a stable intracellular potential for at least 2 min, and a return of the electrical potential to within 2 mV of baseline after withdrawal of the microelectrode to the bathing buffer. Microelectrode input resistance was continuously monitored during impalement by passing a current pulse of 0.1 nA, for 150 ms, through the microelectrode every 10 s using a Winston Electronics Timer (Model A65; Winston Electronics, San Francisco, Calif.). Following impalement, voltage deflections (V) corresponding to the current pulse (I) were used to estimate cell conductance (gce, = I/V). The ionic composition of the standard external solution was (in mmol/L) 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N’-2-ethansulfonic acid (HEPES). The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with tris(hydroxylmethyl)-aminomethane (Tris)-OH. Where indicated, the solution also contained the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol or levetiracetam (100 μM respectively).

GABAA receptor subunit expressionTotal RNA was extracted from 1 x 106 CSCs or NSCs by the commercially available TRIzol method (Invitro-gen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) reactions consisted of the following: 1 μg RNA, 5x reaction buffer (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), 0.5 mM dNTP, 0.5 units RNase inhibitor, 20 pmol oligo(dT) 18 primer, and 20 units Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (MMLV RT). Reactions were incubated at 42°C for 60 min, and terminated at 99°C for 6 min. Five microliters of the reactions were used for the PCR reaction.

The oligonucleotide primers for PCR reactions were designed against human GABAA receptor sequences using an Oligo 5.0 program (National Biosciences, Plymouth, MN). The sequences of human GABAA receptor oligonu-cleotide primers were as follows:

- •

Alpha3 3’-5’CCGTCTGTTATGCCTTTGTATT, 5’-3’ TGTTGAAGGTAGTGCTGGTTT.

- •

Alpha 6 ATTCTGTGGCTAGAAAATGCCC, 3’-5’ GCCGCAGCCGATTGTCATA.

- •

Beta3 3’-5’ GGAGATACCCCCTGGACGAGCA 5’-3’ GGATAGGCACCTGTGGCGAAGA.

- •

Gamma 3 ACTCCTGCCCGCTGATTTTC, 3’-5’ TGTCTGAATGGTGAAGTATCCCA.

- •

Epsilon 3’-5’ ATGCTTCTCCTAAACTCCGCC, 5’-3’ CGACCGTGTTATCAATGACC.

- •

Pi 5’-3’ CGACCGTGTTATCAATGACC, 3’-5’ CCCCAAACACAAAGCTAAAGCA.

These subunits were selected on the basis of previous reports describing discrepant expression in various tumor and non-tumor tissues.12-18 The PCR amplification was carried out in 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 45 s), annealing (57°C, 45 s) and elongation (72°C, 2 min) and with an additional 7-min final extension at 72°C. Finally, 10 ul of the PCR products were run on 2% agarose gels.

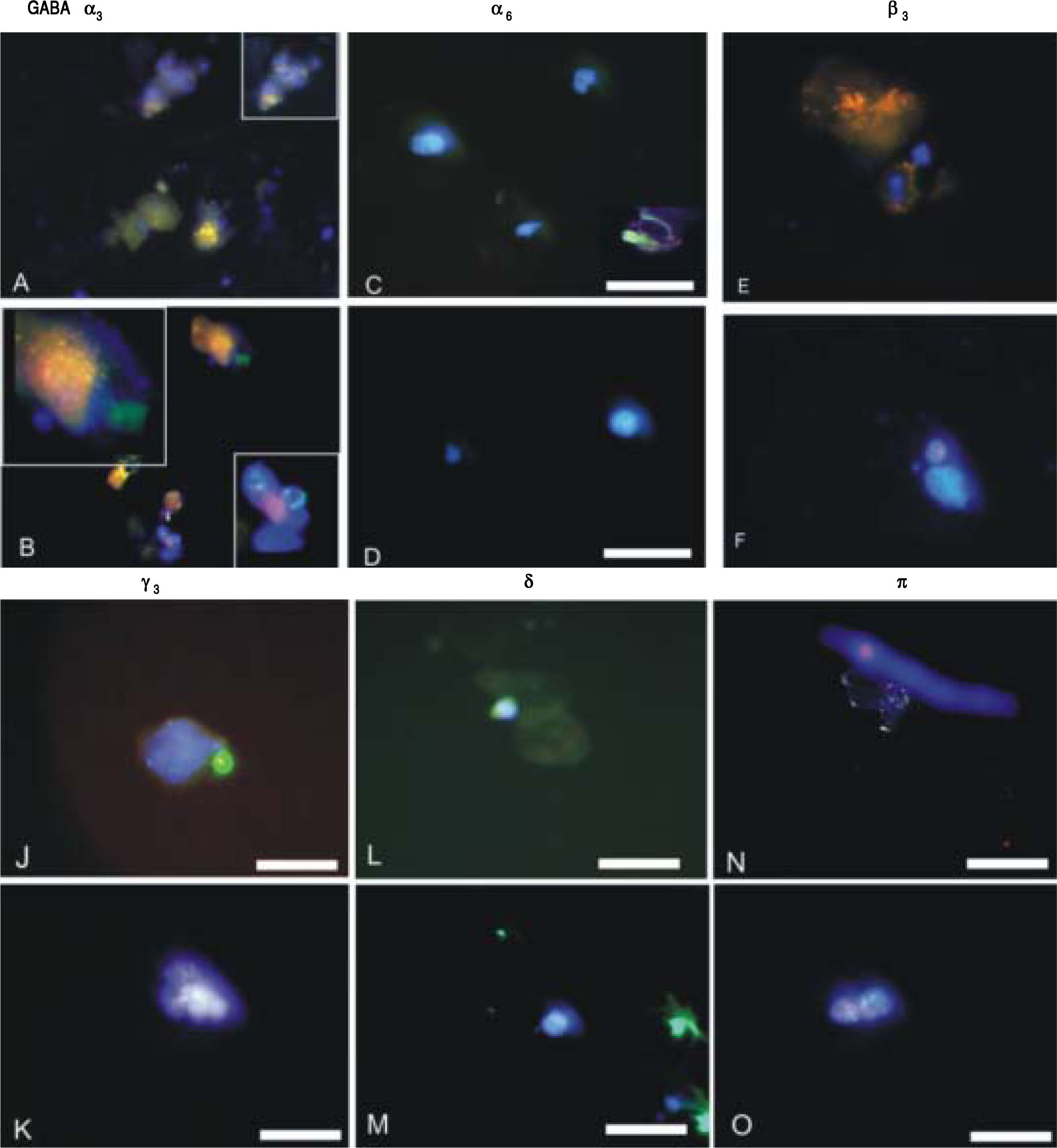

ImmunofluorescenceIsolated CSCs and NSCs were plated on coverslips and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for immunostaining. Mouse monoclonal anti-EpCAM and GABAA receptor subunits α3, α6, β3, γ3, δ and π were employed (Chemicon, Co. Ltd., South Korea). The presence of primary antibodies was detected using Alexa 488 or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Burlington, Ont.). For double immunofluorescence labelling, coverslips were incubated for 24 h at 4°C. Cells were then washed for 1 h at room temperature and incubated for 1 h simultaneously with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA) diluted 1:1000, in combination with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Westgrove Pennsylvania, USA) diluted 1:300. Prior to coverslipping, cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Molecular Probes). Fluorescence was examined on a Zeiss Axioskop2 fluorescence microscope with image capture using Axiovision 3.0 software (Carl Zeiss Canada, Toronto, Ont.). Confocal analyses were performed using an Olympus Fluoview IX70 confocal microscope with image capture using Olympus Fluoview software (Markham, Ont.). Corel Draw software (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, Ont.) was used for image presentation. Immunopositive cells were quantified from at least 3 independent experiments by analyzing an average of 100 cells across multiple fields.

StatisticsStudent t tests were performed for parametric data and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for nonparametric data. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results provided represent the mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated.

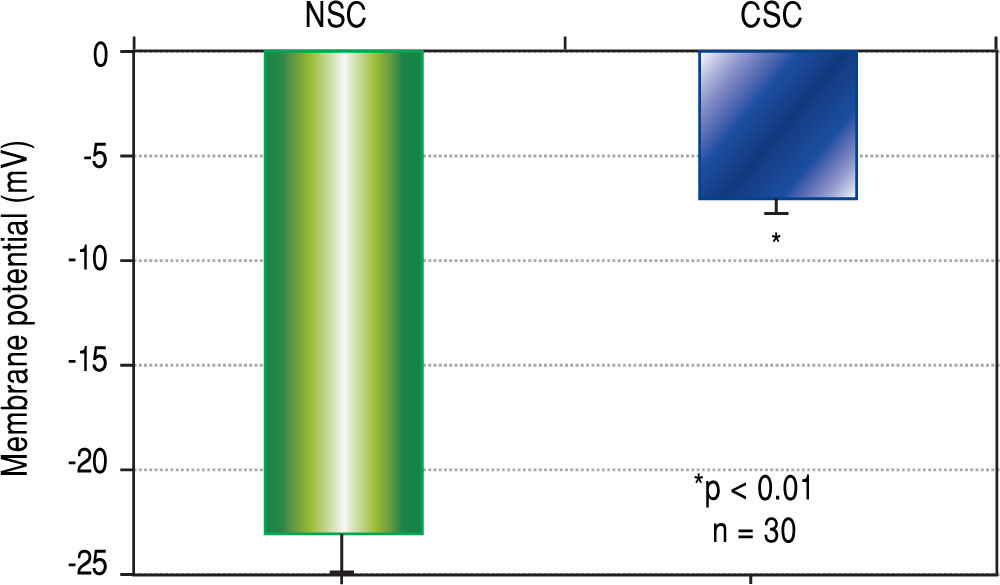

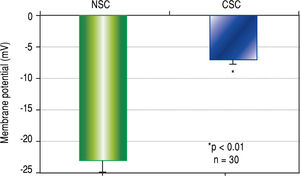

ResultsCellular membrane potential differencesThe results of CSC and NSC PD determinations are shown in Figure 1. Relative to NSCs, CSCs were significantly depolarized i.e. less negatively charged (-7.0 ± 1.3 vs. -23.0 ± 1.4 mV, n = 30, p < 0.01).

Cell membrane potential differences (PDs) in normal stem cells (NSCs) and cancer stem cells (CSCs) derived from healthy human livers and hepatocellular carcinoma tissues respectively, as determined by microelec-trode impalements of isolated cells. The PDs of CSCs were significantly depolarized (p < 0.01) when compared to NSCs.

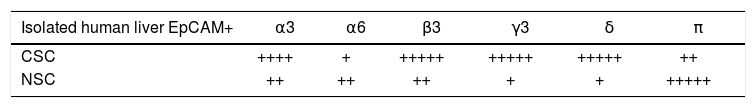

GABAA receptor subunit expression in CSCs and NSCs as determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and immunofluorescence are provided in table 1 and Figure 2 respectively. Both techniques demonstrated that “phasic” GABAA α3 expression prevailed in CSCs whereas “tonic” GABAA α6 expression was expressed to a greater extent in NSCs. Other subunits selected on the basis of previous reports describing their differential expression in tumor versus adjacent non-tumor tissues also revealed different patterns of expression in CSCs and NSCs. Specifically, GABAA(33, y3 and 8 expression was abundant in CSCs whereas GABAAnwas dominant in NSCs.

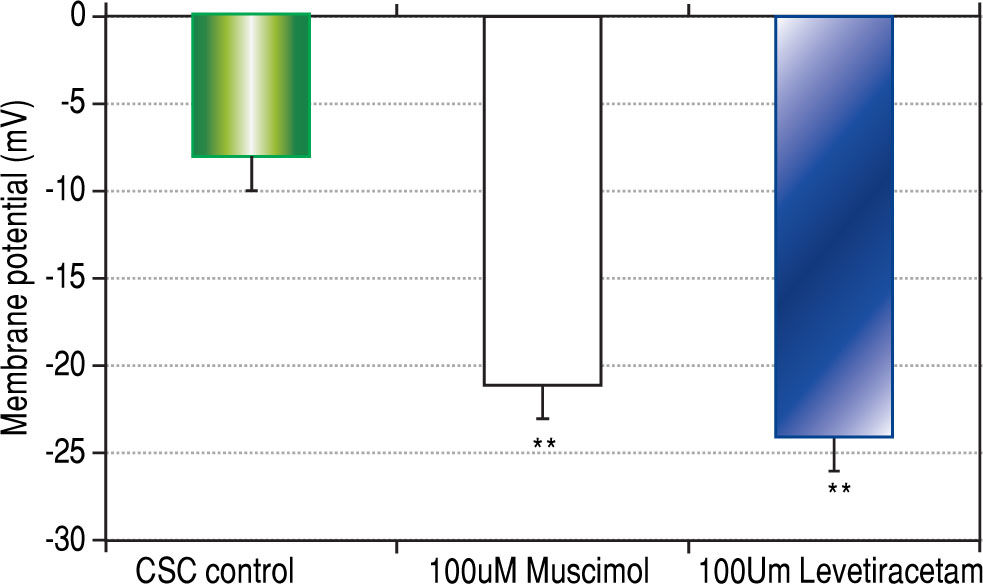

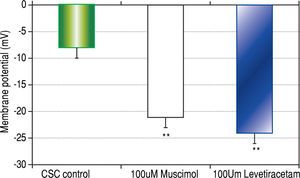

Both CSCs and NSCs significantly (p < 0.01) hyper-polarized following the addition of GABAA receptor agonists muscimol and levetiracetam (Figure 3). However, the extent of hyperpolarization was similar in the two cell populations (CSCs: Δ12.5 ± 1.2 and NSCs: Δ11.0 ± 3.5 mV).

DiscussionThe results of the present study indicate that primary CSCs derived from human HCC are significantly depolarized relative to NSCs derived from the same livers. They also indicate that the differences in membrane PDs are associated with differences in GABAA receptor subu-nit expression which favor phasic rather than tonic GABAergic innervation and thereby, a more depolarized state for CSCs. Finally, they demonstrate that CSCs and NSCs can be hyperpolarized by the addition of specific GABAA receptor agonists.

To date, there have been no reports documenting or comparing membrane PDs in human CSCs and NSCs derived from the liver or other tissues. In the only previous paper specifically designed to determine whether differences in PDs exist in cancer and non-cancer stem cells, we described significantly depolarized CSCs derived from the malignant, human Huh-7 and PLC hepatocyte cell lines when compared to NSCs derived from a non-malignant, rodent WBF-344 cell line.5 However, these findings might well have related to the different species involved as significant interspecies variability has been described for PD determinations.19,20

Unlike the paucity of data regarding PDs in stem cells, there are numerous previous reports describing differences in PD determinations between malignant and non-malignant “mature” cells of the same tissue. For example, we previously documented that mature malignant hepatocytes which constitute the bulk of HCC tissue are significantly depolarized relative to adjacent non-tumor hepatocytes.18 We also reported that the PDs of malignant hepatocyte cell lines are significantly depolarized relative to freshly isolated human hepatocytes.21 Similar findings have been reported in cervical, endometrial, breast, neuronal and muscle tumors by other investigators.22-25 Thus, overall, the results of the present study are in keeping with those of previous reports for the majority of tumor cells and extend the findings to the more clinically relevant, human stem cell populations.

Certain GABAA receptor subunits have been reported to be either upregulated or downregulated in solid organ tumors.12-18 In the present study, we focused on the α3 and α6 subunits because they are instrumental in determining whether GABAergic innervation is phasic (relatively depolarizing) or tonic (relatively hyperpolarizing) respectively.8 Moreover, the relative contributions of α3 and α6 subunit expression serves to define extra-synaptic cell in-nervation which would be more relevant to solid organ tissues such as the liver. Thus, in addition to providing new insights into the mechanism whereby CSCs derived from HCCs are depolarized relative to NSCs, the finding of enhanced GABAA α3 subunit expression in CSCs serves to identify that subunit (in addition to β3, γ3 and δ) as a potential target for immune-mediated HCC therapy.

As mentioned earlier, CSCs tend to be resistant to chemotherapy. The most common explanation for this finding is an upregulation of multi-drug resistant (MDR) genes such as MDR-1 which encode for p-glycoproteins that efficiently export cationic chemotherapeutic agents including doxorubicin from CSCs.26,27 This PD dependent process raises the possibility that by hyperpolarizing CSC PDs, as was achieved in the present study with the addition of GABAA receptor agonists, MDR-mediated export of chemotherapeutic agents might be attenuated and thereby, the chemosensitivity of CSCs enhanced. In addition, because the transition of cells from a primitive to well differentiated phenotype is dependent on a simultaneous transition from a depolarized to hyperpolarized state, activation of CSCs with GABAergic agents could conceivably result in their differentiation and loss of the self-replication property inherent to CSCs.28 Clearly, further research is required to determine whether these theoretical considerations will translate into more effective treatments for HCC.

There are a number of limitations to this study that warrant emphasis. First, CSCs and NSCs were isolated from resected human liver tissues and PD values were not documented in situ. This limitation relates to previous studies that have documented differences in cell PDs when determined in situ versus in vitro.18,19 However, the isolation process employed in the present study was identical for both cell populations and therefore, although absolute values may differ, relative differences should have remained intact. Moreover, because CSCs represent a very small percent of the bulk tumor cell population (< 5%) and NSCs an even smaller percent of non-tumor tissue, recording of CSC and NSC PDs in situ is not feasible with presently available techniques. A second limitation relates to focusing on specific GABAA receptor subunits rather than documenting the expression of all 16 subunits identified to date. As indicated above, the rationale for the more selective approach was based on the relative importance of non-synap-tic GABAergic transmission in non-neuronal tissues and previous studies documenting that specific GABAA receptor subunits are significantly up- or down-regulated in tumor vs. non-tumor tissues.12-18 Yet another limitation was the absence of data regarding the expression of other neuro-transmitter and electrogenic systems. Although we previously reported that nicotinic receptors and Na/K ATPase activity are not perturbed in HCC, these data were derived from the “mature” cell populations of HCC tumors and may not be applicable to stem cell populations.15,18 Finally, the clinical relevance of this study is predicated on the assumption that CSCs play an important role in the development of HCC and although emerging data tend to support that hypothesis, a consensus on the precise role of stem cells in carcinogenesis has yet to be reached.

In conclusion, the results of this study have identified clear distinctions between the PDs and GABAA receptor subunit expression profiles of CSCs and NSCs derived from human HCC and adjacent non-tumor tissues. These findings not only provide important new insights into hepatic carcinogenesis but could conceivably be exploited in future attempts to develop new, more effective therapies for patients with HCC.

Abbreviations- •

CSC: cancer stem cell.

- •

EpCAM: epithelial cell adhesion molecule.

- •

GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid.

- •

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

MDR: multi-drug resistant.

- •

NSC: normal stem cell.

- •

PD: potential differences.

- •

RT-PCR: reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

None.

AcknowledgementsThis research was funded by Kenroc Building Materials Co. Ltd. and the Canadian Liver Foundation. The authors would like to thank Ms R. Vizniak for her prompt and accurate typing of the manuscript.