Background. Alcohol intake has been associated with the bitter taste receptor T2R38. TAS2R38 gene expresses two common haplotypes: PAV and AVI. It has been reported that AVI homozygotes consume more alcohol than heterozygotes and PAV homozygotes. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of the TAS2R38 haplotypes among Mexican-Mestizo population and to analyze its association with alcohol intake.

Material and methods. In a cross-sectional study, a total of 375 unrelated Mestizo individuals were genotyped for TAS2R38 polymorphisms (A49P, V262A and I296V) by a Real-Time PCR System (TaqMan). Haplotype frequencies were calculated. Association of TAS2R38 haplotypes with alcohol intake was estimated in drinkers (DRS) and nondrinkers (NDRS).

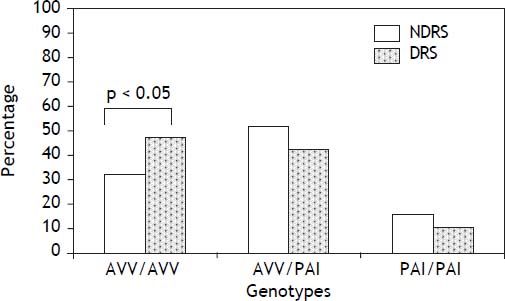

Results. Two haplotypes accounted for over 96% of all haplotypes (AVV, 60%, and PAI, 36.5%). The frequency of AVV homozygotes was significantly higher in DRS than NDRS (47.2 vs. 32.2%, respectively; p < 0.05). Additionally, the AVV/AVV genotype was associated with alcohol intake when compared with heterozygotes and PAI homozygotes (OR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.13-2.84, p < 0.05 and OR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.11-4.48; p < 0.05, respectively).

Conclusions. In conclusion, two TAS2R38 haplotypes (AVV and PAI) prevailed in Mexican-Mestizo population. The novel AVV haplotype was associated with alcohol intake. The high prevalence of this allelic profile in our population could help to explain, at least in part, the preference for alcohol among the Mexicans.

Bitter taste perception is considered an important dietary adaptation,1–3 which is associated with the intake of bitter-tasting foods such as cruciferous vegetables, sharp cheeses, soy products, grapefruit, green tea and coffee.4 However, it has been reported that ethanol (alcohol) also elicits a bitter taste in humans.5,6 Based on the response to the synthetic thiourea bitter-tasting compounds phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP), individuals can be classified as tasters or nontasters as they perceive more and less intensely bitter taste, respectively.7,8 However, the proportion of both PTC/PROP phenotypes varies among different populations worldwide.9 Scientific evidence support that bitter taste perception is mediated by the Taste 2 Receptors (TAS2R), a family of G protein-coupled taste receptors encoded by almost 25 functional TAS2R genes.10 In particular, TAS2R38 has been identified as the gene for PTC sensitivity, which is located on chromosome 7.11

Three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the TAS2R38 gene which encode for amino acid substitutions at position 49 (alanine/proline, A49P), 262 (valine/alanine, V262A) and 296 (isoleucine/valine, I296V) may explain up to 85% of the observed variance in PTC taste sensitivity. Recently, it was demonstrated that alcohol bitterness depends upon the expression of these three TAS2R38 SNPs,12 which may explain the variability in the preference for alcoholic beverages.13–15 Moreover, several TAS2R38 haplotypes corresponding to the amino acids at the three positions have been reported, being PAV and AVI the most common.16 PAV and AVI homozygotes exhibit the highest and lowest bitter taste sensitivity, respectively while PAV/AVI heterozygotes show an intermediate phenotype.17 Consistent with this, several studies have shown that AVI homozygotes consume more alcohol than heterozygotes and PAV homozygotes.18–20 Interestingly, greater bitterness perception may not necessarily induce alcohol rejection since studies have shown that wine expertise can be predicted by the PROP tasting phenotype.21

Mexico is currently one of the leading countries with the highest drinking score and a high mortality rate for alcoholic liver disease. Consequently, the comprehensive analysis of the genetic and environmental factors involved in alcohol intake, including those related to bitter taste perception may help to explain the high alcohol consumption of modern-day admixture Mexicans.22 Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of the TAS2R38 haplotypes among Mexican-Mestizo population and to analyze its association with alcohol intake.

Material and MethodsStudy populationIn a cross-sectional study, a total of 375 unrelated Mestizo individuals from the city of Guadalajara (GDL) in the state of Jalisco were analyzed. The subjects were classified according to the recommendations of alcohol intake to prevent liver damage as drinkers (DRS) and nondrinkers (NDRS).23,24 A medical history questionnaire was designed to register the amount of alcohol intake, which was expressed as:

g ethanol = volume mL x % alcohol x 0.8/100.

The following amounts were considered:

- •

1 shot of tequila = 35 mL (11.2 g ethanol).

- •

1 beer = 330 mL (12.3 g ethanol).

- •

1 glass of red wine = 120 mL (14.4 g ethanol).

Based on the pattern of alcohol consumption in West Mexico, DRS consumed more than two drinks per occasion, while NDRS consumed equal or less than two drinks per occasion.22 Smokers and subjects who had chronic sinus problems or who had any prescribed medication that might affect taste perception were excluded.

TAS2R38 genotypingDNA was extracted from leucocytes by a modified salting-out method.25TAS2R38 genotyping was performed by a Real-Time PCR System (TaqMan, Applied Biosystems, assay numbers C_9506826, C_9506827, and C_8876467; Foster City, CA) on a 96-well format and read by a Step One Plus (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). DNA was used at a final concentration of 70 ng. Conditions of the polymerase chain reaction were 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles of denaturation at 92 °C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C, for 1 min. Genotyping was verified by using positive controls of the DNA samples corresponding to the three possible genotypes in each 96-well plate as well as rerunning 25% of the samples, which were 100% concordant.

Anthropometric measurementsHeight measurement was determined by using a clinical scale with a stadiometer (Rochester Clinical Research, New York, USA) during the patient’s visit. Electrical bioimpedance determined body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) with an INBODY 3.0 analyzer (Analyzer Body Composition, Biospace, Korea).

Biochemical testsTen mL blood samples were drawn by venipuncture after a 12-h fast and separated into two aliquots; one for DNA isolation and another for determination of biochemical tests that included glucose, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) was calculated using the Friedewald formula,26 and very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-c) concentration was calculated as Total Cholesterol - (LDL-c + HDL-c). Dry chemistry determined all biochemical tests on a Vitros 250 Analyzer (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Johnson & Johnson Co, Rochester, NY). For quality control purposes, we used a pooled human serum and a commercial control serum (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Johnson & Johnson Co) to account for imprecision and the inaccuracy of the biochemical measurements. The intra-assay variability (CV%) of biochemical assays was relative to ten repeated determinations of the control serum in the same analytical session, whereas inter-assay CV% for each variable was calculated on the mean values of control serum measured in five analytical sessions. When necessary, the serum was diluted with bovine serum albumin according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Statistical analysesStatistical differences between experimental groups for quantitative and qualitative variables were analyzed by t-student and Chi-square test, respectively with the SPSS software (version 20). Hardy-Wein-berg equilibrium (HWE) and linkage disequilibrium (LD) as well as haplotype frequencies were obtained by using Arlequin software (version 3.1). To analyze the association of TAS2R38 haplotypes with alcohol intake an odds ratio test (OR) was performed in the Epi-info TM7 software (CDC, Atlanta, GA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical guidelinesThe study protocol complied with the ethical guideline for the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Hospital Ethical Committee. All participants filled out a written informed consent.

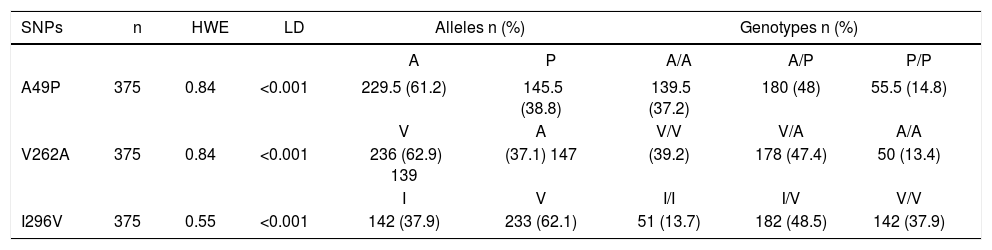

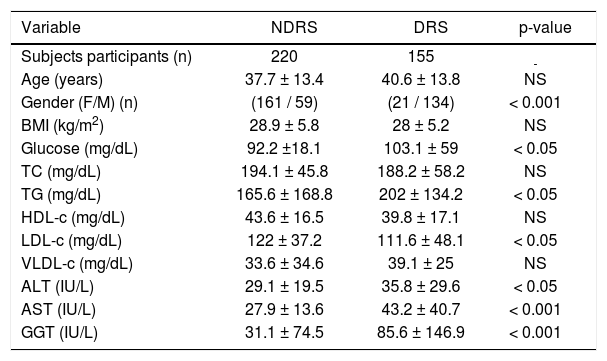

ResultsAllelic and genotype frequencies of the TAS2R38 polymorphisms (A49P, V262A and I296V) are shown in Table 1. The distribution of genotypes was concordant with the HWE. Additionally, the three genetic variants were in strong LD (p < 0.001). Two haplotypes accounted for over 96% of all haplotypes (AVV, 60%, and PAI, 36.5%) whereas the remaining four haplotypes were rare (PVV, 2%) or extremely rare (AVI, < 1%, AAI, < 1%, and PVI, < 1%). Of the most frequent haplotypes, 36% were AVV homozygotes, 45.1% heterozygotes and 12.8% PAI homozygotes. Demographic and biochemical characteristics of DRS and NDRS are shown in Table 2. No differences for the variables of age, BMI, TC, HDL-c and VLDL-c were found. By contrast, DRS had a higher proportion of men and higher levels of glucose, TG, LDL-c, ALT, AST and GGT than NDRS. The frequency of AVV homozygotes was significantly higher in DRS than NDRS (47.2 vs. 32.2%, respectively; p < 0.05) (Figure 1) and this genotype was associated with alcohol intake when compared with heterozygotes and PAI homozygotes (OR = 1.79, CI 1.13-2.84, p < 0.05 and OR = 2.23, CI 1.11-4.48; p < 0.05, respectively).

Allelic and genotypie frequencies of the TAS2R38 polymorphisms (A49P, V262A and I296V).

| SNPs | n | HWE | LD | Alleles n (%) | Genotypes n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | P | A/A | A/P | P/P | ||||

| A49P | 375 | 0.84 | <0.001 | 229.5 (61.2) | 145.5 (38.8) | 139.5 (37.2) | 180 (48) | 55.5 (14.8) |

| V | A | V/V | V/A | A/A | ||||

| V262A | 375 | 0.84 | <0.001 | 236 (62.9) 139 | (37.1) 147 | (39.2) | 178 (47.4) | 50 (13.4) |

| I | V | I/I | I/V | V/V | ||||

| I296V | 375 | 0.55 | <0.001 | 142 (37.9) | 233 (62.1) | 51 (13.7) | 182 (48.5) | 142 (37.9) |

N: number. HWE: Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium. LD: Linkage Disequilibrium. HWE and LD data are reported as p-value of chi-square test. Allelic and genotype frequencies are expressed as percentage.

Demographic and biochemical characteristics of NDRS and DRS.

| Variable | NDRS | DRS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects participants (n) | 220 | 155 | - |

| Age (years) | 37.7 ± 13.4 | 40.6 ± 13.8 | NS |

| Gender (F/M) (n) | (161 / 59) | (21 / 134) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 ± 5.8 | 28 ± 5.2 | NS |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 92.2 ±18.1 | 103.1 ± 59 | < 0.05 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 194.1 ± 45.8 | 188.2 ± 58.2 | NS |

| TG (mg/dL) | 165.6 ± 168.8 | 202 ± 134.2 | < 0.05 |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 43.6 ± 16.5 | 39.8 ± 17.1 | NS |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 122 ± 37.2 | 111.6 ± 48.1 | < 0.05 |

| VLDL-c (mg/dL) | 33.6 ± 34.6 | 39.1 ± 25 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 29.1 ± 19.5 | 35.8 ± 29.6 | < 0.05 |

| AST (IU/L) | 27.9 ± 13.6 | 43.2 ± 40.7 | < 0.001 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 31.1 ± 74.5 | 85.6 ± 146.9 | < 0.001 |

Average values are expressed as mean ± SD. DRS: drinkers. NDRS: non drinkers. BMI: body mass index. TC: total cholesterol. TG: triglycerides. HDL-c: high density lipoprotein cholesterol. LDL-c: low density lipoprotein cholesterol. VLDL-c: very low density lipoprotein cholesterol. ALT: alanine aminotransferase. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. GGT: gamma-glutamyl-transferase. NS: not significant. n: number.

Globally, the most common TAS2R38 haplotypes are AVI and PAV.16 However, in this study, the AVV and PAI haplotypes were the most predominant among the study population. Although the PAI haplotype has been identified in other populations, its frequency was extremely low.27 In contrast, the AVV haplotype found in this study has not been reported elsewhere to date. Its high frequency may be due to the unexpected dominance of the valine variant at position 296 distributed among the I/V-V/V genotypes. Functional expression studies demonstrate that the presence of alanine at position 49 and valine at position 262 diminishes receptor function, whereas the variation in position 296 had little effect.28 Notably, the AVI and AVV haplotypes have the same effect of not responding to the bitter taste compounds PTC/PROP (non tasters), whereas the PAV and PAI variants respond equally strong (tasters).

In this study, we also demonstrated that the frequency of the AVV homozygotes was higher in DRS than NDRS and this genotype was associated with alcohol intake when compared with heterozygotes and PAI homozygotes. These findings are consistent with other reports evaluating the effect of the TAS2R38 haplotypes with alcohol intake,18–20 and may be explained because decreased receptor function by AVV haplotype causes an increase in taste perception thresholds, which ultimately leads to the consumption of a greater amount of alcohol. Moreover, although it has been reported that gender influences alcohol intake,29 in this study male gender was not a confounder factor despite the high amount of men in the drinkers group because it was not related to alcohol intake matched by TAS2R38 haplotype.

In regards to the bitter taste phenotype and alcoholism relationship, some studies have reported an association between alcoholism and PROP tasting ability,30,31 while other studies have not found such association.32–34 However, these discrepancies may be caused by methodological flaws in sample size, tasting classification, drinking habits and the effect of other tastes.

In Mexico, the alcoholic beverage preferences are heterogeneous. For instance, tequila is the main beverage consumed in West Mexico; while “pulque” and “mezcal” are preferred in the central region, in contrast to beer in the northern and southern parts of the country.21 Thereby, further studies are needed to elucidate the relation between the taste of these beverages and its consumption. In addition to bitter taste, the role of other tastes in alcohol intake has been analyzed. For example, it was reported that subjects who are at risk of alcoholism by having an alcoholic father, rated salty and sour solutions as more unpleasant than those with no such paternal history.35,36 Moreover, several studies suggest that sweet-liking is also associated with a paternal history of alcohol dependence.37–40

Because excessive and chronic alcohol consumption are inherent features required to reach alcoholism, TAS2R38 may be a promising candidate gene for alcoholic dependence.41 However, no evidence has been found that TAS2R38 haplotypes influence alcohol dependence in high-risk women of African-American origin.19 Thus, population-specific features are modulated by genetic and environmental factors affecting alcohol intake that require further investigation.21,42 For instance, specific alleles such as the dopamine receptor DRD2*A1, the alcohol-metabolizing enzymes ADH2*A1, CYP2E1*C1 and ALDH2*A1 and the transporter proteins involved in lipid metabolism APOE*2 and FABP2*Thr54 have been associated with alcoholism and chronic liver disease in the Mexican population.43–46 However, these findings may differ with those reported in other populations worldwide.

ConclusionIn conclusion, two TAS2R38 haplotypes (AVV and PAI) prevailed in Mexican-Mestizo population. The novel AVV haplotype was associated with alcohol intake. The high prevalence of this allelic profile in our population could help to explain, at least in part, the preference for alcohol among the Mexicans.