Objective. Gallbladder disease and cardiovascular disease share risk factors. Both have a great impact on the economics of health systems. There is evidence suggesting an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with gallbladder disease, but the association of gallbladder disease with other risk factors for cardiovascular disease is unclear. The aim of this study is to analyse the relationship between cholecystectomy for gallstone disease and risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Material and methods. This is a case-control study comparing subjects undergoing cholecystectomy with controls without gallbladder disease or cholecystectomy. Demographic, anthropometric, and biochemical data were recorded and risk factors for cardiovascular disease were assessed. The data were analysed with chi square test, student t test and logistic regression (univariate and multivariate).

Results. Seven hundred and ninety-eight subjects were included. The multivariate analyses demonstrated that, compared with controls, cases had an increased prevalence of metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease (odds ratio (OR) 2.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8-4.8, p = 0.001), including type 2 diabetes mellitus (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1-4.5, p = 0.018), high blood pressure (OR 5.1, 95% CI 2.6-10.1, p = 0.001), and high cholesterol levels (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3-5.5, p = 0.004). No differences were observed in the incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion. Patients undergoing cholecystectomy had an increased prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, independent of age, sex, or body mass index.

Gallstone disease (GD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are both considered public health problems and have increased in prevalence through time, especially in the Western world.12 CVD remains the leading cause of mortality worldwide. Approximately 33% of all deaths are caused by CVD, which includes type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease, and hypertension.3 In the United States, 800,000 cholecystectomies are performed every year; this affects the economy of the individual and also the economy of the public and private health systems.4 Currently, the pathogenesis of gallstones is well known: gallstone formation involves environmental, genetic, and organic factors, ethnicity, and dietary habits.57 More than 80% of gallstones are formed from cholesterol, as is atheroma.2 Based on the third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), Ruhl & Everhart8 analysed data from 14,228 subjects in whom the prevalence of GD was 7.1% and of cholecystectomy 5.3%. Patients with GD had increased mortality for CVD (hazard risk = 1.4; 95% CI 1.2-1.7), which can be explained because both diseases share risk factors such as age, obesity, diabetes, and components of the metabolic syndrome.9

Recently we analysed the thickness of the intima and media layers of the carotid artery in patients with GD and found that 38.7% of these patients presented with an increased thickness of this artery compared with 20% of controls.10 In another study, patients with CHD had an increased risk of developing GD (OR = 2.84, 95% CI: 1.33-6.0, p < 0.007), the main associated factors being body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR).9 Another study in patients with breast cancer found a high incidence of myocardial infarction in patients with GD.11 Little information has been published regarding the association between cholecystectomy for GD and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Recently CVD, diabetes mellitus, and a history of cerebrovascular accident were reported as independent risk factors for acute cholecystitis.12 Despite the broad association between GD and CVD, there is no clear information regarding this relationship in subjects undergoing cholecystectomy.

ObjectiveTo investigate the association between cholecystectomy for GD and risk factors for CVD.

Material and MethodsStudy populationWe conducted a retrospective study in a private teaching hospital in Mexico City (Medica Sur Clinic & Foundation). Three hundred and ninety-nine patients who underwent cholecystectomy for GD during the period 2006 to 2011 were included. As controls, 399 asymptomatic subjects without gallstones or previous cholecystectomy were included. Asymptomatic subjects were recruited from preventive medical consultations and were matched with cases for age, sex, and BMI.

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of The Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation as conforming to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Physical examinationBody weight was measured, in light clothing and without shoes, to the nearest 0.10 kg. Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. Overweight was defined as a BMI ranging from 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 and obesity was defined when BMI > 30 kg/m2. Waist circumference (to the nearest 0.1 cm) was measured at the midpoint between the lower border of the rib cage and the iliac crest, and hip circumference was similarly obtained at the widest point between hip and buttock. Three blood pressure (BP) readings were obtained at 1 min intervals, and the second and third systolic and diastolic pressure readings were averaged and used in the analyses.

Analytical proceduresPlasma glucose and liver function of subjects in the fasting state was measured in duplicate using an automated analyser. The coefficient of variation for a single determination was 1.5%. Cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were measured by enzymatic colorimetric methods, using CHOL, HDL-C plus (second generation) and triglyceride assays, respectively, from Roche Diagnostics Co (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol concentrations were calculated using the Friedewald formula.13

Cardiovascular riskCVD risk factors were defined as:

- •

Overweight and obesity (BMI > 25 kg/m2 and > 30 kg/m2 respectively).

- •

Hypertension (BP > 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication).

- •

Low HDL-cholesterol (< 1.0 mmol/L in men and < 1.3 mmol/L in women).

- •

High LDL-cholesterol (> 4.3 mol/L).

- •

High triglycerides (> 2.3 mmol/L), or T2DM (use of diabetes medication or reported physician diagnosis).

Means and standard deviations were used to describe the distributions of continuous variables in comparisons between healthy and cholecystectomy subjects. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was applied because of the non-normal distribution of some of these variables. By means of cross-tabulations, the risks associated with the probability of having risk factors for CVD were estimated. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with the independent variables coded in a binary form. Statistical significance was determined by Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To derive adjusted OR (adjusted for confounders) associated with the probability of risk factors for CVD, multivariate unconditional logistic regression analyses were conducted. Multicollinearity in the adjusted models was tested by deriving the covariance matrix. All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistics program SPSS/PC version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

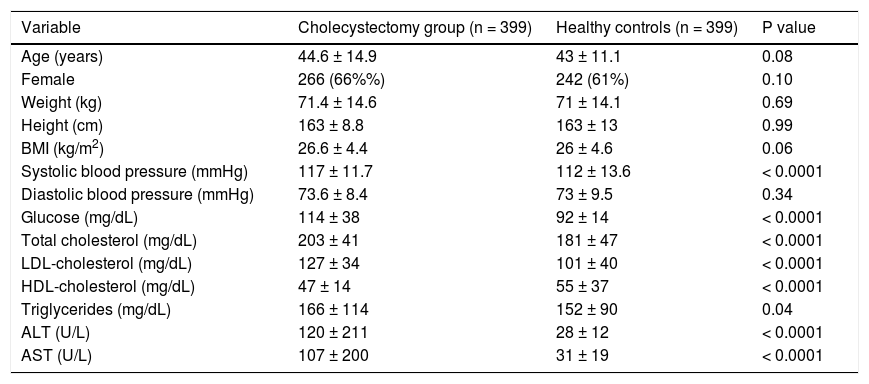

ResultsSeven hundred and ninety-eight subjects were included, 399 who underwent cholecystectomy in the case group, and 399 controls. There were no significant differences between the groups in age (44 ± 14 vs. 43 ± 11 years, p = 0.08), sex (female 66 vs. 60%, p = 0.09), or BMI (26.6 ± 4.4 vs. 26 ± 4.6, p = 0.06). Those patients undergoing cholecystectomy had higher systolic (117 ± 12 vs. 112 ± 14 mmHg, p < 0.001) but not diastolic BP. They also had higher levels of fasting glucose (114 ± 38 vs. 92 ± 14 mg/ dL, p < 0.001), triglycerides (166 ± 114 vs. 152 ± 90 mg/dL, p = 0.04), and total cholesterol (203 ± 41 vs. 181 ± 47 mg/dL, p < 0.001). Similar differences were observed for cholesterol lipoproteins (Table 1).

Characteristics of patients undergoing cholecystectomy and healthy controls.

| Variable | Cholecystectomy group (n = 399) | Healthy controls (n = 399) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.6 ± 14.9 | 43 ± 11.1 | 0.08 |

| Female | 266 (66%%) | 242 (61%) | 0.10 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.4 ± 14.6 | 71 ± 14.1 | 0.69 |

| Height (cm) | 163 ± 8.8 | 163 ± 13 | 0.99 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 26 ± 4.6 | 0.06 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 117 ± 11.7 | 112 ± 13.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73.6 ± 8.4 | 73 ± 9.5 | 0.34 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 114 ± 38 | 92 ± 14 | < 0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 203 ± 41 | 181 ± 47 | < 0.0001 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 127 ± 34 | 101 ± 40 | < 0.0001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 47 ± 14 | 55 ± 37 | < 0.0001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 166 ± 114 | 152 ± 90 | 0.04 |

| ALT (U/L) | 120 ± 211 | 28 ± 12 | < 0.0001 |

| AST (U/L) | 107 ± 200 | 31 ± 19 | < 0.0001 |

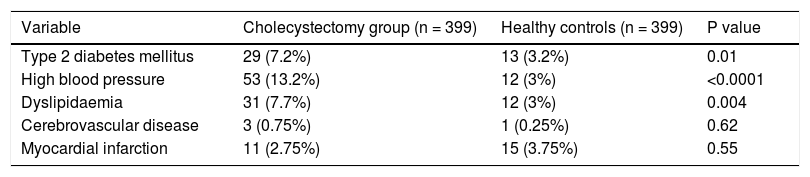

The case group had a higher prevalence of T2DM (7.2 vs. 3.2%, p = 0.01), high BP (13.2 vs. 3%, p ≤ 0.0001), and dyslipidaemia (7.7 vs. 3%, p = 0.004). The prevalence of a history of myocardial infarction did not differ between the groups (2.7 vs. 3.7%, p = 0.55) (Table 2).

Risk factors and previous history of cardiovascular disease.

| Variable | Cholecystectomy group (n = 399) | Healthy controls (n = 399) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 29 (7.2%) | 13 (3.2%) | 0.01 |

| High blood pressure | 53 (13.2%) | 12 (3%) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 31 (7.7%) | 12 (3%) | 0.004 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 (0.75%) | 1 (0.25%) | 0.62 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 (2.75%) | 15 (3.75%) | 0.55 |

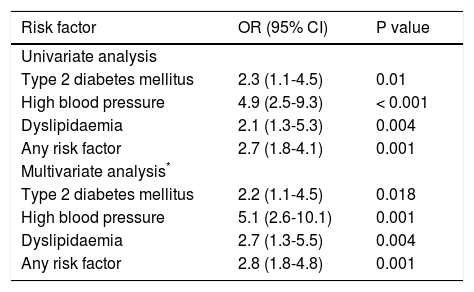

Univariate analysis demonstrated that patients undergoing cholecystectomy had increased risk of T2DM (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.19-4.5, p = 0.01), high BP (OR 4.9, 95% CI 2.5-9.3, p < 0.001), and dyslipidaemia (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3-5.3, p = 0.004). The risk of having any disease considered as a risk factor for CVD was also increased (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.8-4.1, p = 0.001). In multivariate analysis (adjusted for age, sex, and BMI), the risk of T2DM (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1-4.5, p = 0.018), high BP (5.1, 95% CI 2.6-10.1, p = 0.001), and dyslipidaemia (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3-5.5, p = 0.004) remained higher (Table 3). There were no differences in the risk for acute myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular disease (data not shown).

Increased risk of cardiovascular disease risk factors in subjects undergoing cholecystectomy versus healthy controls.

| Risk factor | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 2.3 (1.1-4.5) | 0.01 |

| High blood pressure | 4.9 (2.5-9.3) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.1 (1.3-5.3) | 0.004 |

| Any risk factor | 2.7 (1.8-4.1) | 0.001 |

| Multivariate analysis* | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 2.2 (1.1-4.5) | 0.018 |

| High blood pressure | 5.1 (2.6-10.1) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2.7 (1.3-5.5) | 0.004 |

| Any risk factor | 2.8 (1.8-4.8) | 0.001 |

GD and CVD are both prevalent health problems worldwide. The pathogenesis of both diseases is multifactorial, including environmental and genetic factors. One of the main shared physiopathological mechanisms of both diseases involves cholesterol accumulation. In cholelithiasis, the liver secretes bile supersaturated with cholesterol,2 while in CVD, including CHD, stroke, aortic atherosclerosis, and peripheral artery disease, the pathogenesis involves the accumulation of cholesterol in atheroma plaque.3

In this study we demonstrate an increased prevalence of risk factors for CVD in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Although there was a trend towards association with differences in age, sex, and BMI, the increased prevalence of CVD risk factors remained after multivariate analysis. A recent necropsy study reported an association of gallstone disease with diabetes and with increased BMI, but not with cardiovascular disease.14 In the same study, BMI (in women) and increased age were important risk factors for GD. In our study these confounders were properly controlled, and we observed an increased prevalence of T2DM in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. In both studies, hard outcomes in terms of prevalence of confirmed CVD were not increased in the subjects with GD. In our study at least, this could be explained by the young age of our subjects and a sample size that was underpowered to assess this uncommon outcome in this age group. Relevant information from death certificate data in Sweden shows that 26% of the mortality in patients who underwent cholecystectomy for acute or chronic gallbladder disease was because of CVD.15 In the NHANES III, a prospective population-based sample, GD (gallstones or cholecystectomy) was associated with increased overall mortality. The prevalence of gallstones was 7.4% and of cholecystectomy 5.3%. During an 18-month follow-up, the overall allcause mortality was 16.5% and cardiovascular mortality 6.7%.8

Atherosclerosis is a slow progressive disease associated with metabolic syndrome, and is the main pathogenic mechanism of CVD, with high morbidity and mortality. GD, including patients having chole-cystectomy, may be considered as a risk factor for developing CVD. This is concordant with the previous data from asymptomatic GD that showed an increased incidence of CVD risk factors (metabolic syndrome)9 and with increased intima-media thickness.13

ConclusionPatients undergoing cholecystectomy have a higher prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. This categorises an important segment of the population as high-risk.

Study Highlights- •

What is current knowledge. Patients with gallstone disease have an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome.

Gallstone disease is a factor for increased markers of cardiovascular disease.

- •

What is new here. Patients undergoing chole-cystectomy have an increased prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

This increase is independent of classical confounders including age, sex, and body mass index.

Cholecystectomy is an indicator of classic cardiovascular’s risk factors.