There are rare instances where patients with acute hepatitis A virus infection subsequently developed autoimmune hepatitis. The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis in this setting is challenging. Furthermore, information on treatment with steroids or other immune suppressants, duration of therapy and possibility of treatment discontinuation is currently unclear. Here we report a case series of four patients with histology proven autoimmune hepatitis after hepatitis A virus infection. We describe the presenting features, diagnosis, treatment and long-term outcomes of these cases. This case series provides a insight into the clinical presentation and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis after hepatitis A infection with interesting take home points for clinical hepatologists.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic liver disease characterized by circulating autoantibodies, elevated immunoglobulin G levels and characteristic histologic changes and when untreated can lead to acute liver failure or chronic liver disease resulting in cirrhosis. While etiology of AIH is not known in it’s entirety, an association with human leucocyte antigen types DR3 and DR4 has been described [1]. Various viral triggers for AIH has been described including Epstein Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, HIV and hepatitis A, B, C and D viruses specifically in a genetically susceptible individual [2].

Rare instances of AIH after acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection have been reported [3–6]. In an observational study, Vento et al. prospectively followed 58 healthy first and second degree relatives of 13 patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis for 4 years. Three of the 58 subjects had subclinical infection with HAV with a simultaneous rise in antibodies directed against asialo glycoprotein receptor (a constituent of lipoprotein complex) located on the hepatocytes. They proposed that HAV infection could lead to a defect in suppressor inducer T cells which in turn can lead to autoimmune response mediated by these antibodies [7]. Since then, about ten case reports have been reported with varying treatment regimens and outcomes [6]. With this limitation, the diagnosis of AIH in the setting of HAV and the decision to start immunosuppressants continues to be a management dilemma for hepatologists. To add to the dilemma, there have been reports of prolonged acute HAV infection that can mimic AIH [8].

In late 2017, the state of Indiana experienced an outbreak of HAV that allowed us to identify four patients with AIH after HAV. In the current case series, we describe the natural history, clinical features, treatment duration, and long-term outcomes of these patients.

2CASE SERIESAll patients in the current series were Caucasian, with a mean age of 51 (±16) years (Table 1). Three were women without underlying chronic liver disease. The remaining patient was a man with a recent diagnosis of cirrhosis of undetermined etiology. The risk factors identified for HAV exposure were person to person through the fecal-oral route or intravenous drug use. Presenting symptoms included fatigue, jaundice, nausea, and vomiting, or pruritus. The diagnosis of acute HAV was made through positive hepatitis A IgM serology associated with abnormal liver tests. Values for liver biochemistries, autoantibodies, and immunoglobulin G levels of all patients are presented in Table 1. The mean duration between the initial diagnosis of acute HAV infection, and workup for evaluation of AIH was 37 (± 19) days.

Select demographics, time intervals between the initial episode of acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection and subsequent diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), liver biochemistries and outcomes.

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50 | 49 | 34 | 72 | ||||

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Female | ||||

| Race | Caucasian | Caucasian | Caucasian | Caucasian | ||||

| Comorbidities | None | T2DM, HTN, Cirrhosis | Sjogren’s, Hypothyroidism | HTN | ||||

| Mode of transmission | Person to person contact and injection drug use | Unknown | Travel to endemic area | Person to person contact | ||||

| Duration (days) | ||||||||

| Between HAV and AIH diagnosis | 39 | 9 | 25 | 51 | ||||

| Between HAV and initiation of immune suppression | 46 | NA | 26 | 66 | ||||

| Between initiation of immune suppression and normalization of liver enzymes | 38 | NA | 65 | 146 | ||||

| Liver tests at the time of diagnosis | HAV | AIH after HAV | HAV | AIH after HAV | HAV | AIH after HAV | HAV | AIH after HAV |

| ALT (U/L) | 1001 | 1741 | 42 | 65 | 1795 | 366 | 1875 | 310 |

| AST(U/L) | 308 | 898 | 51 | 107 | 1697 | 319 | 1932 | 367 |

| ALK(U/L) | 715 | 398 | 129 | 109 | 482 | 119 | 175 | 112 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.4 | 3 | 42.5 | 45.7 | 5.3 | 1 | 3 | 1.5 |

| INR | 0.93 | 1.05 | 2.54 | 2.76 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.52 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis related | ||||||||

| Immunoglobulin IgG (mg/dL) | 1190 | 1800 | NA | 2680 | NA | 2930 | NA | 3800 |

| Autoantibodies | Negative | SMA positive | ANA and SMA positive | Negative | SMA positive | Negative | SMA positive | |

| Duration of follow up (days) | 15 months | 45 days | 21 months | 18 months | ||||

| Outcomes | On mycophenolate mofetil | Death from liver failure | On azathioprine | Discontinued immunosuppression | ||||

ANA: antinuclear antibody, SMA: smooth muscle antibody, NA: not available, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALK: alkaline phosphatase, INR: international normalized ratio, T2DM: diabetes mellitus type 2, HTN: hypertension.

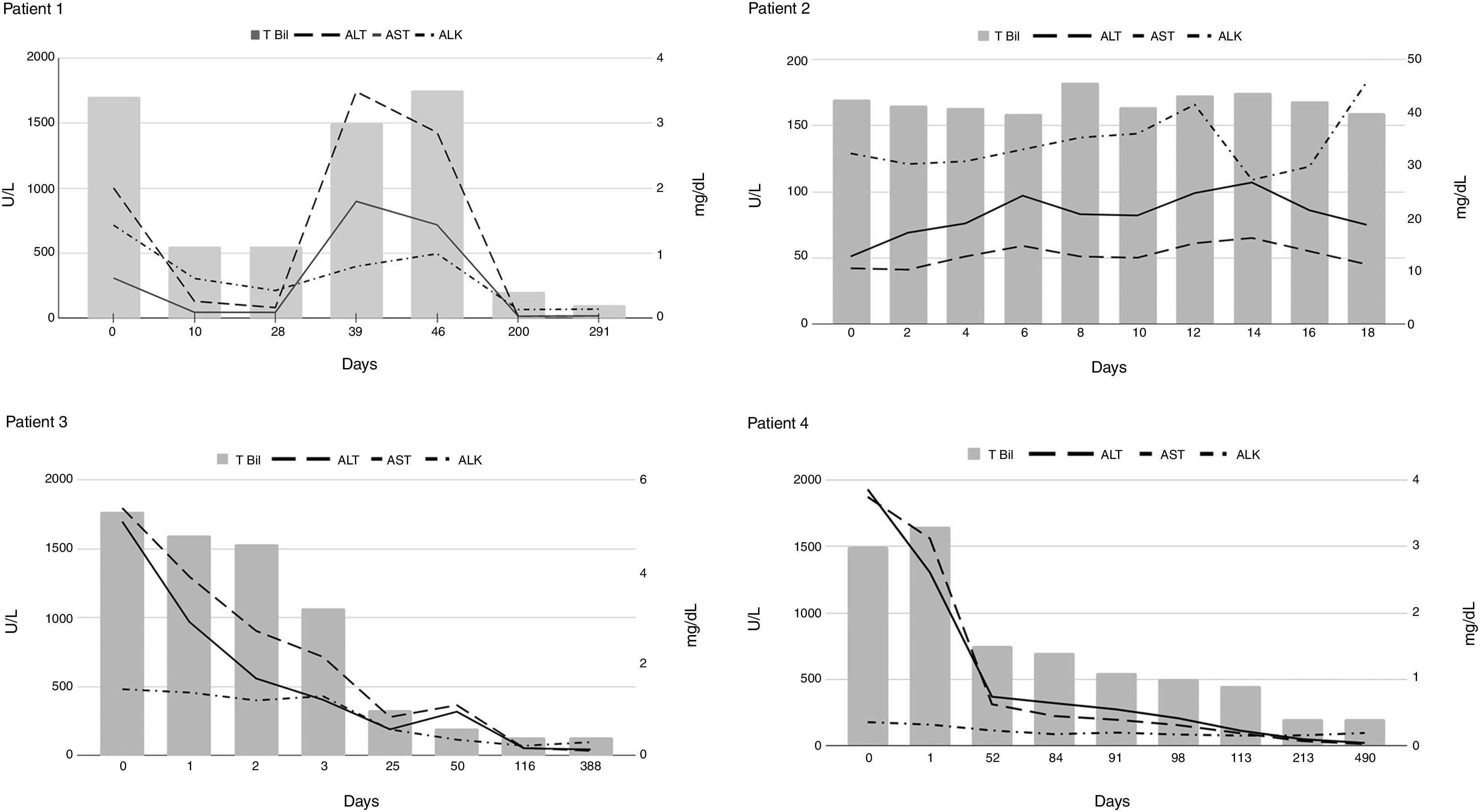

The first case in this series was diagnosed with AIH when she presented with worsening jaundice and elevated liver tests forty days after an initial improvement in symptoms from HAV (Fig. 1, Patient 1). Her liver biopsy showed subacute hepatitis with patchy spotty and zonal necrosis. The prominent plasmacytosis in the infiltrate was somewhat unusual for uncomplicated HAV and was supportive of AIH. The second case was a man who was diagnosed with cirrhosis of unclear etiology two months before the presentation (Fig. 1, Patient 2). He initially presented to another facility with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) from acute HAV and was referred to our institution for further management. A trans-jugular liver biopsy revealed cirrhotic architecture characterized by dense fibrous bands that contained a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. There was extensive interface hepatitis consistent with AIH. The third case was that of a young woman with Sjogren’s disease and hypothyroidism was diagnosed with acute HAV when presented with elevated liver tests and constitutional symptoms. Due to the presence of autoantibodies, a liver biopsy was performed, and it showed acute and chronic hepatitis with marked interface activity and profound portal inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, plenty of plasma cells, and neutrophils supportive of AIH. However, steroids were not started right away due to acute HAV. During follow up a repeat liver biopsy showed features of persistent AIH (Fig. 1, Patient 3) resulting in initiation of treatment. The fourth case was an older woman who presented to our institution due to persistent elevations in aminotransferases two months after acute HAV. A liver biopsy performed showed acute and chronic hepatitis with marked activity and numerous plasma cells suggestive of AIH. Interestingly, multiple noncaseating portal and lobular granulomas were also observed, raising concern for overlap syndrome. However, her antimitochondrial antibody was negative, and her alkaline phosphatase levels were in the normal range (Fig. 1 Patient 4).

Autoantibodies were negative at the presentation in 3 of the four patients. Interestingly, these three patients subsequently developed positive serology for smooth muscle antibody (SMA) at 1:80 titers but not for the antinuclear antibody (ANA). Immunosuppressive therapy was initiated in patients 1, 3, and 4 with subsequent normalization of liver tests in 83 (± 56) days. Patient 2, with underlying cirrhosis, did not receive immunosuppressive therapy due to concomitant sepsis and ACLF that lead to his death. In one patient (patient 4), immunosuppressive therapy was continued for approximately 13 months before discontinuation.

3DISCUSSIONSome interesting observations in the current case series include: (1) approximate two-month lag between acute HAV and subsequent diagnosis of AIH, (2) seroconversion with exclusive SMA positivity, (3) prompt improvement and normalization of liver enzymes in approximately three months, and (4) discontinuation of immunosuppression in some. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the largest series of autoimmune hepatitis in a background of acute hepatitis A infection. In addition, this case series is disctinct in having information on treatment with longitudinal follow-up.

Pathophysiologic mechanisms of association between HAV and AIH are still unclear. While molecular mimicry between viral and hepatic epitopes has been demonstrated between HSV 1, hepatitis C antigens and liver antigens, it hasn’t been in case of hepatitis A virus [9–11]. Reports of HAV infection triggering immune related diseases like Guillain-syndrome [12] and hemolytic anemia [13] support this theory. Since AIH won’t typically occur after every HAV infection, host factors should have a role in this interaction. In South American children, HLA DR13 allele, a marker for autoimmune hepatitis was associated with prolonged liver damage after HAV infection, a similar susceptibility might exist in adults as well [14] and could explain the host factor in this epidemiologic association.

Interestingly, in the current case series, all patients developed AIH after HAV within two months of the initial presentation. Most patients showed an improvement in liver enzymes before the 2nd bump in the liver tests. Based on the current case series, we think it might be prudent to monitor all patients with acute HAV for at least three months or until normalization of liver tests, whichever occurs later. In addition, the possibility for discontinuation of immunosuppression (patient 4) is reassuring and has been reported previously [6].

In summary, lack of normalization of liver tests after HAV should prompt concern for AIH, particularly in those with seroconversion to SMA positivity. Furthermore, seroconversion of SMA and not ANA is interesting and additional studies need to be done to understand this phenomenon. Rising incidence of autoimmune hepatitis [15] coupled with ongoing sporadic HAV epidemics build up a case for considering universal HAV immunization in unimmunized adults especially in regions with high proportion of susceptible adults.

Informed consentInformed patient consent was obtained for publication of case details.

FundingNo financial support.

Conflicts of InterestAll authors declare no conflict of interest in the preparation of this manuscript, including financial, consultant, institutional, and other relationships that might lead to bias.