Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome (APS) is a combination of different autoimmune diseases. The close relationship between immune-mediated disorders makes it mandatory to perform serological screening periodically in order to avoid delayed diagnosis of additional autoimmune diseases. We studied a patient with type 1 diabetes (T1D) who later developed an autoimmune thyroid disease (ATD) and was referred to our hospital with a serious condition of his clinical status. The patient was suffering from an advance stage of celiac disease (CD), the delay in its diagnosis and in the establishment of a gluten-free dietled the patient to a severe proteincalorie malnutrition. Later, the patient developed an autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). We consider that clinical deterioration in patients with APS should alert physicians about the possible presence of other immune-mediated diseases. Periodic screening for autoantibodies would help to prevent delayed diagnosis and would improve patient’s quality of life.

Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (APS) are a combination of different autoimmune diseases.1,2 Based on clinical criteria, four main types of APS have been described:1 type 1, which is also called autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy, and type 2, which is known as Schmidt syndrome, both are well-defined entities with an important genetic background and with Addison’s disease as the main observed affection;3 type 3 is a heterogeneous disease without involvement of the adrenal gland that comprises a variable combination of entities;4–6 and type 4 represents a miscellaneous type encompassing pathologies which are not included in the other types.

APS-3 is the most frequent APS due to the high prevalence of the combination of autoimmune thyroid disease (ATD) and type 1 diabetes (T1D).7 Celiac disease (CD), characterized by small intestinal enteropathy triggered by the ingestion of gluten-containing foods,8 can be part of APS-3. Diagnostic criteria for CD include clinical suspicion, specific auto-antibodies (IgA anti-endomysial (EMA), IgA anti-type 2 transglutaminase (-TG2) and IgG anti-deamidatedgliadin peptides (-DGP)), HLA-DQ2- and/or HLA-DQ8-encoding haplotypes and duodenal damage. Despite these established criteria, CD diagnosis is sometimes difficult, like in the absence of specific antibodies, which has been reported with a variable prevalence (6-22%).9 Instauration of a gluten-free diet (GFD) with a short diagnostic delay is crucial to avoid complications, including development of additional immune-mediated conditions. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an inflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology,10 with a well-established association with other autoimmune diseases, being ATD and CD the most frequent diseases observed.11,12

We present an atypical case of a middle-aged man with a diagnosis of APS-3 with ATD and T1D, complicated with a delayed diagnosis of CD, which carried a serious deterioration in his clinical condition and probably contributed to the subsequent development of AIH.

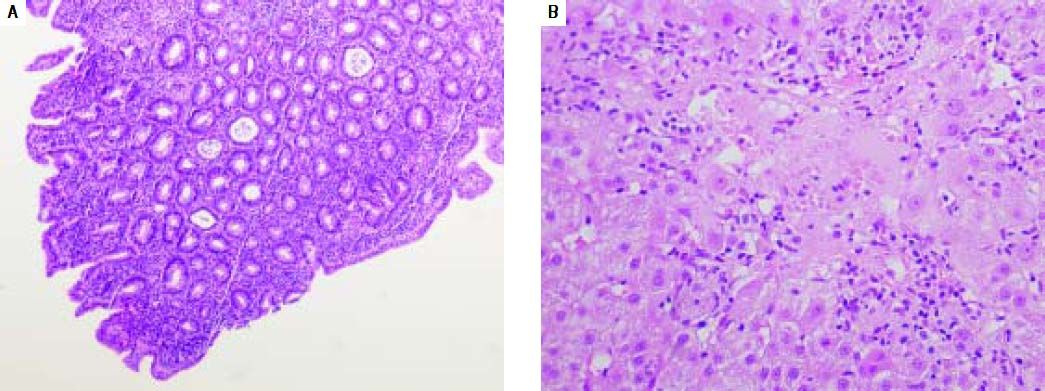

Case ReportA 56 year-old Caucasian man was diagnosed with T1D when he was 27 years old. Twenty-three years later, in 2009, he began with poor control of his blood sugar, showing 8,4% of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and fatigue. In January 2010, he was diagnosed with auto immune hypothyroidism based on positive results for anti-thyroperoxidase antibodies. In May 2010, despite he started hormone replacement treatment, he presented poor control of both diseases. To dismiss any pancreatic entity, an abdominal ultrasound was made, which resulted normal. Three months later, he began with severe diarrhea, dyspepsia, important weight loss and anemia. Tumor markers were negative, and in September, a slight increase of hepatic enzymes was observed with 9.7% of HbA1c. Several diagnostic tests were made later: an abdominal ultrasound, an endoscopic ultrasound, a computed tomography and a positron emission tomography-computed tomography; all resulted normal. At the end of 2010, a magnetic resonance cholangiography showed normal results and, for the first time, CD was considered as a possible cause. However, CD was discarded by negative serology (absence of anti-TG2 antibodies). Microbiological studies in feces resulted negative and, as the patient clinical condition was gradually getting worse, he was referred to the Gastroenterology Unit at the Hospital Clínico San Carlos. In January 2011, we received the patient with a serious worsening in his clinical status, with severe protein-calorie malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies. New serological tests for CD were performed, which resulted positive for IgA anti-TG2, but negative for EMA, and the alleles encoding HLADQ2.5 (DQB1*02-DQA1*05) were detected in the genetic test. A colonoscopy and upper endoscopy were normal, but the duodenal biopsy showed histological damage compatible with CD (Figure 1). The patient started a GFD in January 2011. Due to the wide spectrum of clinical symptoms, in the same serum tested for CD specific antibodies, serological markers for other diseases were studied. We found a speckled antinuclear antibody (ANA) at mild titter (Table 1). In early March 2011, he referred clinical improvement after beginning GFD with no diarrhea, but he continued with moderate proteincalorie malnutrition, and he was admitted into the hospital to complete the study of the hypertransaminasemia. The physical examination showed conjunctival jaundice, painless and soft abdomen with normal characteristics and absence of hepatomegaly. Laboratory values on admission revealed that the patient had acute hepatitis (Table 1). He denied alcohol abuse and consumption of alternative or herbal medications. Albeit at low risk for viral hepatitis, hepatitis A, B and C serologies were made and resulted negative, he was also negative for HIV. Given his hypertransaminasemia and his positivity for ANA, the main suspicion was AIH, which was confirmed in April 2011 after performing a liver biopsy (Figure 1), starting with the recommended treatment: prednisone and azathioprine. From this point, the GFD response was remarkable, with weight gain, without diarrhea and with restoration of the protein-calorie malnutrition, hemoglobin levels and decrease of the HbA1c levels (7%). Anti-TG2 antibodies became negative (Table 1). Currently, the patient is being followed up in the CD specific consultation in coordination with the Endocrinology Unit. He is asymptomatic and refers a great improvement in his quality of life.

Histological images from duodenum and liver biopsy. A. Small bowel mucosa shiowing decreased villous height, crypt hyperplasia and intraepithelial lymphocytes (>30/100 enterocytes); compatible with 3b degree in the Marsh-Oberhuber classification. B. Hepatic biopsy showing moderate interface hepatitis with moderate chronic inflammatory infiltrate and foci of necrosis; compatible with autoimmune etiology, 3,431 in Knodell score.

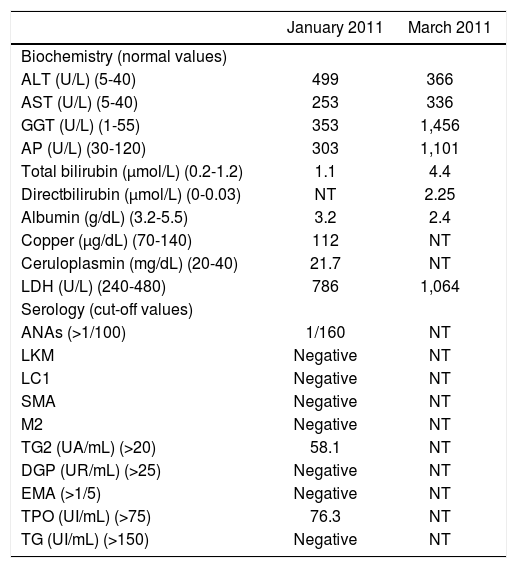

Results of the different analysis performed to the patient in January and March 2011.

| January 2011 | March 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemistry (normal values) | ||

| ALT (U/L) (5-40) | 499 | 366 |

| AST (U/L) (5-40) | 253 | 336 |

| GGT (U/L) (1-55) | 353 | 1,456 |

| AP (U/L) (30-120) | 303 | 1,101 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) (0.2-1.2) | 1.1 | 4.4 |

| Directbilirubin (μmol/L) (0-0.03) | NT | 2.25 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (3.2-5.5) | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Copper (μg/dL) (70-140) | 112 | NT |

| Ceruloplasmin (mg/dL) (20-40) | 21.7 | NT |

| LDH (U/L) (240-480) | 786 | 1,064 |

| Serology (cut-off values) | ||

| ANAs (>1/100) | 1/160 | NT |

| LKM | Negative | NT |

| LC1 | Negative | NT |

| SMA | Negative | NT |

| M2 | Negative | NT |

| TG2 (UA/mL) (>20) | 58.1 | NT |

| DGP (UR/mL) (>25) | Negative | NT |

| EMA (>1/5) | Negative | NT |

| TPO (UI/mL) (>75) | 76.3 | NT |

| TG (UI/mL) (>150) | Negative | NT |

NT: nottestedd. ALT: alanine aminotransferase. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. GGT: gamma glutamyltransferase. AP: alkaline phosphatase. LDH: lactate dehydrogenase. ANA: antinuclear antibodies. LKM: liver kidney microsomal 1. LC1: liver citosol 1. SMA: smooth muscle antibody. M2: antimitochondrial antibody. TG2: anti-type 2 transglutaminase. DGP: anti-deamidatedgliadin peptide. EMA: anti-endomysium. TPO: thyroperoxidase antbodies. TG: thyroglobulin antibodies.

APS-3 is defined by the presence of ATD without Addison’s disease and at least one organ-specific autoimmune disease, such as T1D (type 3a), pernicious anemia, CD or AIH (type 3b) or vitiligo, alopecia or myasthenia gravis (type 3c).1,13 T1D and ATD are endocrine disorders with high prevalence in European populations (1 and 9%, respectively). Both entities appear commonly together, with around 30% of T1D diagnosed patients showing also ATD.7,14 Shared susceptibility genetic variants contribute to develop these autoimmune entities and in consequence APS-3.15 This genetic background also increases the probability of developing other autoimmune diseases.

CD is also an immune-mediated disease with a strong genetic influence. Co-morbidity of CD with T1D and ATD is well established and people suffering from these two diseases are considered at high risk of developing CD.9 A strict GFD is the only accepted treatment for CD, which is effective to improve patients’ health, to reduce the occurrence of complications and, in the case of these co-morbidities, to ameliorate glycemic control in T1D and to allow a proper absorption of the hormone replacement treatment used for hypothyroidism. Further, a good adherence to a GFD has been suggested to prevent the development of other autoimmune diseases.16

AIH is an inflammatory disorder with high prevalence. A liver biopsy is needed for AIH diagnosis, in association with clinical, analytical and immunological data.17 This last criterion allows to distinguish between type I (smooth muscle and/or ANA) and type II (liver kidney microsomal-1 or liver cytosol-1 antibodies).10 The etiology is unknown, but along with CD, AIH shows a strong association with the HLA-DRB1*03 and HLA-DRB1*04 alleles.18,19

Here, we present the case of a middle-aged man with APS-3a (T1D and ATD) complicated with CD and AIH.

In order to avoid unnecessary diagnostic tests, it is important to alert physicians that CD should not be dismissed with a negative serology, since as high as 22% of seronegative CD among all diagnosed patients has been reported.9 There is no consensus regarding the screening strategy for CD in adult patients with T1D, but in children some guidelines recommend to perform CD screening at the time of T1D diagnosis, annually for the first next years and later every two years or even more frequently when clinical suspicion or first-degree relatives with CD exist.20 Autoimmune serology screening was not performed to the patient until he was a middleage man. Despite it is not possible to certainly know it, AIH could have been avoided with an earlier CD diagnosis and the establishment of a strict GFD, which had also prevented the severe malnutrition suffered by the patient. After starting the GFD, the clinical response was remarkable, with great improvement in few months and complete restoration of his health status. Considering all the past medical history of our patient and the four autoimmune diseases presented: T1D, autoimmune hypothyroidism, CD and AIH, we conclude that his clinical condition was part of an APS type 3 with characteristics of subtype a and b.

In conclusion, to our knowledge this is the first case report of an APS-3 with these four autoimmune associated diseases, highlighting the complexity and severity of the clinical course of APS. Based on our results and in view of the patient’s clinical condition, we believe that all physicians should keep in mind that a patient with an autoimmune disease is at increased risk to develop other immune-mediated diseases, making necessary to screen for additional auto-antibodies. We hope that this case will help other physicians in clinical practice to improve patient’s quality of life and reduce unnecessary diagnostic tests.

Abbreviations- •

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

- •

AP: alkaline phosphatas.

- •

AIH: autoimmune hepatitis.

- •

ANA: antinuclear antibodies.

- •

anti-TG: anti-thyroglobulin antibodies.

- •

anti-TG2: anti-type 2 transglutaminase.

- •

anti-TPO: anti-thyroperoxidase antibodies.

- •

APS: autoimmune polyglandular syndromes.

- •

ATD: autoimmune thyroid disease.

- •

ATS: aspartate aminotransferase.

- •

CD: celiac disease.

- •

DGP: anti-deamidatedgliadin peptides.

- •

EMA: anti-endomysial.

- •

GFD: gluten-free diet.

- •

GGT: gamma glutamyltransferase.

- •

HbA1c: glycatedhaemoglobin.

- •

Ig: immunoglobulin.

- •

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase.

- •

NT: not tested.

- •

T1D: type 1 diabetes.

All the authors, Dieli-Crimi R, Núñez C, Estrada L and López-Palacios N, declare no conflict of interests.

Financial SupportThe authors are supported by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (AES 2011, PI11/00614) - FONDOS FEDER.

ConsentThe described individual gave written informed consent prior to be included in the study.