Drug allergy is a type B adverse drug reaction, which is unpredictable and difficult to prevent or manage. In patients who have a previous history of drug allergy it must be confirmed by laboratorial diagnosis. However, the diagnostic test remains a major problem in clinical practice. Skin testing is validated for some drugs, such as penicillin, but not for others. Provocation test is a confirmatory test but bears the risk of severe reactions. Lymphocyte transformation test is a reliable test but is considered as a research tool. This review addresses the most recent published literature regarding the techniques which have already been developed as well as the new tests that can be promising alternatives for diagnosis of drug allergy.

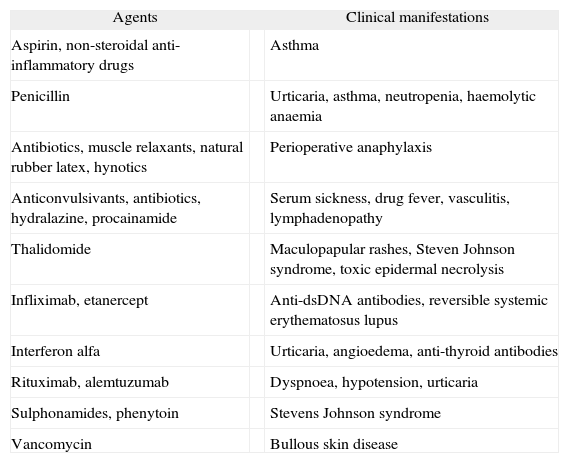

The percentage of the population who reports a history of penicillin allergy is estimated to be 0.7-10 %; however, only 20–30 % of the patients have IgE-mediated allergy 1. Adverse drug reactions (ADR) are considered to be an important public health problem and can be life-threatening. ADR is classified into two main types: type A reactions, which are dose dependent and predictable. These kinds of reactions constitute 70–80 % of adverse drug reactions; and type B, which are unpredictable adverse drug reactions, include idiosyncrasy, drug intolerance, or drug allergy, and may comprise approximately 10–15 % of all ADR 2,3. Clinical manifestations of drug allergy include anaphylaxis, bronchospasm, dermatitis, fever, granulocytopenia, haemolytic anaemia, hepatitis, lupus erythematosus-like syndrome, nephritis, thrombocytopenia, and vasculitis 4. Symptoms and signs without demonstration of being an immunological process are classified as non-immune hypersensitivity drug reactions, and they are generally related to nonspecific histamine release, to nonspecific complement activation, to bradykinin accumulation or to induction of leukotriene synthesis in type I hypersensitivity reactions 5. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics are most often implicated in drug allergies, besides anaesthetic drugs, latex, insulin, and immunomodulators 3,6,7 (Table I).

Clinical manifestations of drug allergy

| Agents | Clinical manifestations | |

| Aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Asthma | |

| Penicillin | Urticaria, asthma, neutropenia, haemolytic anaemia | |

| Antibiotics, muscle relaxants, natural rubber latex, hynotics | Perioperative anaphylaxis | |

| Anticonvulsivants, antibiotics, hydralazine, procainamide | Serum sickness, drug fever, vasculitis, lymphadenopathy | |

| Thalidomide | Maculopapular rashes, Steven Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis | |

| Infliximab, etanercept | Anti-dsDNA antibodies, reversible systemic erythematosus lupus | |

| Interferon alfa | Urticaria, angioedema, anti-thyroid antibodies | |

| Rituximab, alemtuzumab | Dyspnoea, hypotension, urticaria | |

| Sulphonamides, phenytoin | Stevens Johnson syndrome | |

| Vancomycin | Bullous skin disease | |

Data adapted from 3,6-7. Vervloet and Durham, 1998; Hepner et al., 2003; Greenberg, 2006.

Drug allergy reactions are generally classified according to Coomb's classification 6. Type I include IgE-mediated reactions, such as urticaria, anaphylaxis, and asthma; type II comprises IgM and IgG-cytotoxic mechanisms (e.g. blood cell dyscrasias); type III are related to soluble IgG and IgM immune complexes (e.g. vasculitis, nephritis). Type IV reactions include distinct manifestations (e.g. maculopapular exanthema, bullous exanthema, acute, generalized exanthemous pustulosis) according to the kind of cytokines secreted by T cells. In this type of reaction, a subclassification has been suggested according to the distinct effector cells responsible for the lesions 8. The type I hypersensitivity reactions are called immediate reactions when they occur within one hour after the drug intake and the common manifestations are systemic anaphylaxis, urticaria, angioedema; they are called accelerated when they occur between 1 to 72 hours after receiving the drug, and the most frequent manifestations are urticaria and maculopapular rashes. Types II to IV hypersensitivity reactions occur in general after 72 hours of the drug intake 9. The most frequent clinical manifestations caused by betalactamic drugs, which are the commonest implicating agents of drug hypersensitivity, are anaphylaxis (immediate reaction); maculopapular exanthema (late reaction) and isolated urticaria (occurs at any time) 10. In a follow-up study done in two hospitals in Fortaleza, Brazil, it has been verified that from 130 paediatric patients exposed to oxacillin, a drug included in the list of essential medicines, 20.8 % presented drug adverse reactions, in a mean time of 14days after the drug exposure 11. Half of the patients had fever and 35.7 % showed cutaneous rashes.

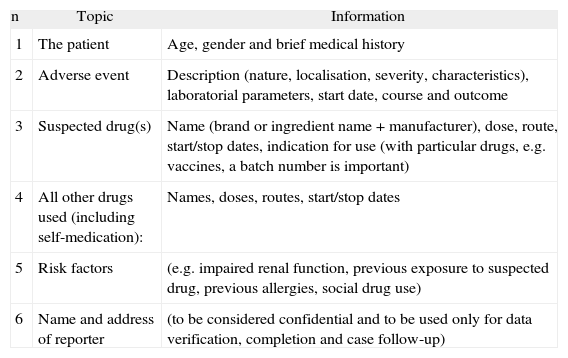

A pharmacovigilance evaluation can be done for monitoring a drug adverse reaction. A case report in pharmacovigilance can be defined as “a notification relating to a patient with an adverse medical event (or laboratory test abnormality) suspected to be induced by a medicine” 12. In general, case reports describe suspected adverse drug reactions 12. Various approaches have been developed for determining the likelihood of a causal relationship between drug exposure and adverse events, based on four main considerations, which are: the association in time (or place) between drug administration and event, pharmacology (including current knowledge of nature and frequency of adverse reactions), medical or pharmacological plausibility (signs and symptoms, laboratory tests, pathological findings, mechanism) (Table II).

Reporting information for associating causal relationship between drug exposure and adverse events (UMC-WHO, 2000)

| n | Topic | Information |

| 1 | The patient | Age, gender and brief medical history |

| 2 | Adverse event | Description (nature, localisation, severity, characteristics), laboratorial parameters, start date, course and outcome |

| 3 | Suspected drug(s) | Name (brand or ingredient name + manufacturer), dose, route, start/stop dates, indication for use (with particular drugs, e.g. vaccines, a batch number is important) |

| 4 | All other drugs used (including self-medication): | Names, doses, routes, start/stop dates |

| 5 | Risk factors | (e.g. impaired renal function, previous exposure to suspected drug, previous allergies, social drug use) |

| 6 | Name and address of reporter | (to be considered confidential and to be used only for data verification, completion and case follow-up) |

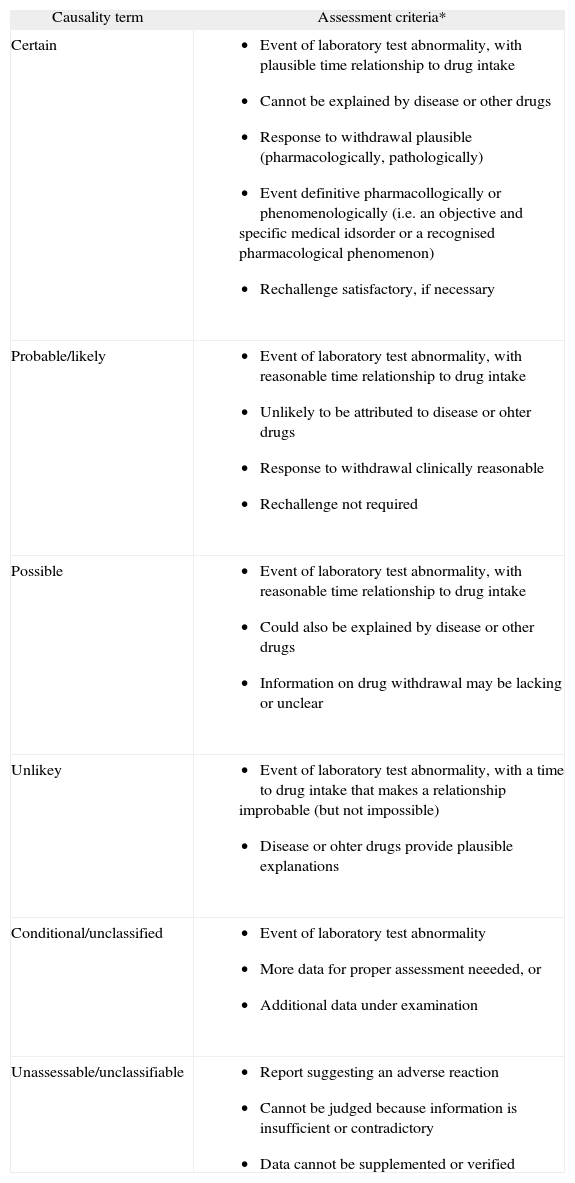

The Uppsala Monitoring Centre (the UMC)/WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring 12 has proposed a way for assessing causality categories, which have the advantages of being internationally agreed and easy to use (Table III).

Assessment criteria for determining causality categories for drug adverse reactions11 (The UMC/Who, 2000)

| Causality term | Assessment criteria* |

| Certain |

|

| Probable/likely |

|

| Possible |

|

| Unlikey |

|

| Conditional/unclassified |

|

| Unassessable/unclassifiable |

|

In the evaluation of a possible adverse drug reaction, a careful investigation of the medical history as well as the laboratorial parameters is extremely important 13,14.

Clinical history investigationA well-kept history is essential to help in the investigation of adverse drug reaction and should include: (1) timing of the onset, course and duration of symptoms; (2) description of clinical and evolutive features; (3) temporal relationship of symptoms with medication use; (4) a detailed list of all drugs taken during the onset of the reactions; (5) personal and familiar history of adverse drug reactions; and (6) co-associated diseases. Some laboratory parameters, such as full blood count; platelet count; blood sedimentation rate; serum creatinine; bilirubin; alkaline phosphatise; transaminases; biopsy, among others, and specific confirmatory tests (skin and patch tests, in vitro assays for specific IgE, also serology to check for some infectious diseases, such as cytomegalovirosis, infectious mononucleosis, parvovirosis, hepatitis B and C 13,14.

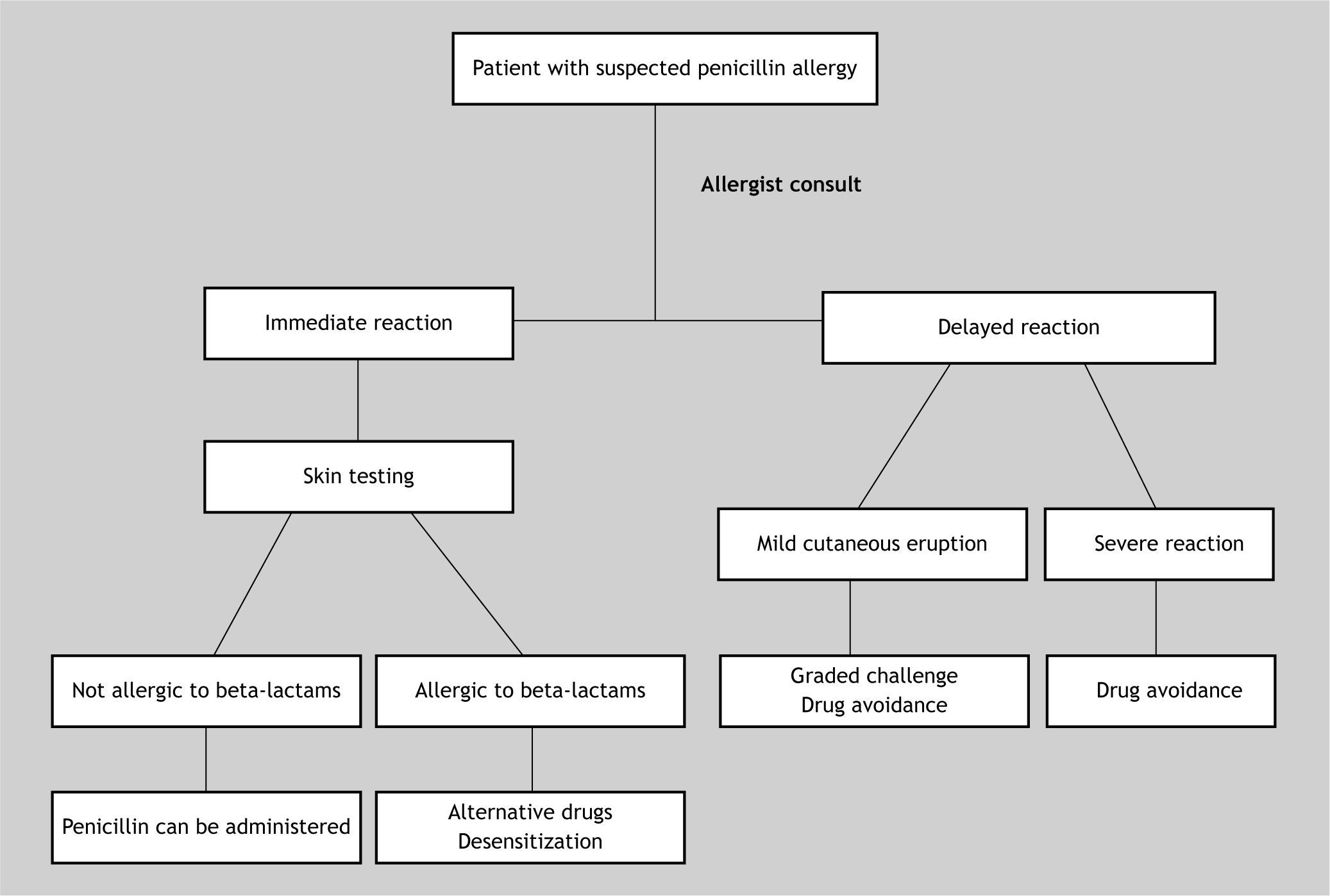

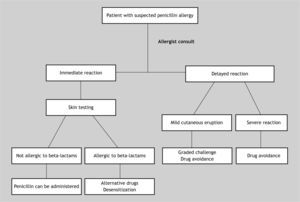

Diagnostic testsSkin testingThe diagnostic value of skin tests varies depending on the drug involved in the reaction. They should be done 4 to 6weeks after the reaction is resolved 5. Their sensitivity and predictive value are considered to be very good for penicillin, myorelaxant, heterologous sera, enzymes; satisfactory for vaccines, hormones, opiates; and poor or unknown for local anaesthetics, sulphonamides, iodine radiocontrast media, non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory drugs, cephalosporin 5. Skin testing for penicillin is the only test regularly used for diagnosis of drug allergy 15. The majority of patients with negative results for major and minor determinants of penicillin will tolerate the drug without risk of a severe immediate reaction 16.

Penicillin is one of the most useful antimicrobial drugs 9. A percentage of 20 % of patients admitted to a hospital refer to have allergy to the drug; however, most of these reports are unreliable 17 and make the physicians prescribe alternative antibiotics, which in general are more expensive, can be associated with toxic effects, and can lead to antibiotic resistance 1. Allergic reactions to penicillin are estimated to occur in 2 % of the patients treated with the drug and most of them are maculopapular or urticarial rashes 9.

Penicillin test should be performed in every patient with a background history of penicillin allergy who needs a therapy with antibiotics 18. The risk of systemic reactions to penicillin skin tests is considered to be very low and may be related to incorrect dose of the drug and the lack of performing the prick test before the intradermal test 16. It is important to remember that skin testing may give false-negative results for 1 to 2weeks or even longer after an episode of anaphylaxis 9 (Fig. 1).

A clinical practice guideline for penicillin skin testing in patients who have a history of penicillin allergy does not increase the costs nor improve financial savings, instead, it increases the percentage of eligible patients for skin testing and, on the other hand, it reduces the necessity of alternative antibiotics 1. It is necessary to take into account that the skin testing for penicillin is useful only for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated reactions to penicillins, not for delayed reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, or other reactions which are not IgE-mediated 9. The penicillin skin test has a negative predictive value of 99 % and a positive predictive value of 50 % 9, when it includes major and minor determinants of the drugs. Because minor determinants are not commercially available, some authors have suggested a dilution of penicillin G, to a concentration of 10,000 units/ml with 0.9 % sodium chloride 17. However, the diluted solution should be freshly prepared 9. Using benzyl penicilloyl as the major determinant, commercially named Pre-Pen, and diluted penicillin G, the negative predictive value of the test is 97 % 9. Nonetheless, the Pre-Pen solution is nowadays unavailable commercially 15,16, which makes penicillin allergy diagnosis very difficult.

Penicillin skin testing has been proposed to be performed by using lab made reagents. Sarti 19 has performed penicillin skin tests in 6,764 patients in an outpatient clinic, by employing fresh diluted penicillin G (PG) and hydrolysate penicillin as minor determinant mixtures (MDM). His data showed that only 96 patients presented positive results. None of the 6,668 patients with negative skin tests re-exposed to penicillin showed any immediate systemic reaction. According to the author, MDM correlates well with diluted penicillin G and can be employed for diagnosing patients susceptible to immediate severe reactions, such as oedema of the larynx and anaphylactic shock; although it could miss some accelerated reactions which are mainly caused by the major determinants. In our country, the Ministry of Health has adopted the mentioned schedule for penicillin drug allergy diagnosis 20.

The Center for Diseases Control 21 states that as no proven alternatives to penicillin are available for treating neurosyphilis, congenital syphilis or syphilis in pregnant women, it is recommended that if the major determinants are not available, patients with a history of immediate IgE-mediated reactions should be desensitised in a hospital service.

In general, penicillin skin testing is useful for detecting any beta-lactam antibiotics 18; however, it is important to note that penicillins share the beta-lactamic ring structure and the thiazolidine rings, but not necessarily the R side chains 22. It is possible that the patient has non cross-reactive responses to various beta lactam antibiotics 23.

It is estimated that 50 % of patients who experienced immediate reactions to penicillin will have a negative skin test after 5years, and 75–80 % will be negative at 10years 9. Nonetheless, penicillin is no longer considered the most commonly prescribed p-lactam 24, therefore it is recommended to include other determinants in skin tests such as amoxicillin and cephalosporin 24,25. According to the data from Blanca et al. 24 in patients who suffered penicillin allergy adverse reactions after treatment, the drugs most involved in the reactions were amoxicillin (87.8 %), followed by benzopenicillin (8.1 %), ampicillin (2.7 %), and cloxacillin (1.3 %).

In vitro IgE-RAST/CAP and ELISA testingThe radioallergosorbent test (RAST), cellulose fluorescent assay-IgE (CAP-IgE) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting anti-drug IgE has variable specificity and sensitivity. For instance, a negative result does not exclude allergy to penicillin, as the assays detect only IgE to the major determinant; however, a positive result can indicate an increased risk for allergic reactions 9,16. The specificity and sensitivity of the CAP-IgE for p-lactam are 85.7-100 % and 12.5-25.0 %, respectively, depending on the initial clinical manifestations 26. The positive predictive values are considered to be high in severe clinical conditions, such as anaphylactic shock 26. Therefore it could be useful in these situations if the skin test is negative, in order to avoid the necessity of drug provocation 24,26. However, the sensitivity and specificity of the in vitro IgE antibodies test decrease more than one year after the allergy episode 26.

Drug provocation testThe drug provocation test is recommended to confirm drug hypersensitivity reactions by the European Network for Drug Allergy from the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology 10,27. The test is cumbersome but can be considered as a reference test when skin tests are not available or not validated 5,28. It should be performed in cases of inconclusive or negative skin and/or CAP-IgE tests in patients with history of immediate drug allergy 29. In most cases, the same route of administration in the clinical history is used, unless the oral form of the culprit drug is available 10.

Increasing doses of a suspected drug are given at 0.5 to 1-h intervals until the full age/weight-adjusted dose is achieved, and depending on the protocol, this procedure may take 1, 2 or more days 23,28. H1-antihistamines and p-blockers should be denied for 2 and 5days, respectively, before the drug provocation test 27. Placebo challenges may be necessary to avoid false positive reactions 29. False negative results can occur and could be explained by cofactors such as exercise, sunlight, and tolerance induction 27. Contraindications for the test are patients with severe comorbidities such as cardiac, hepatic, renal or other diseases and patients who had experienced severe life-threatening reactions as with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, vasculitis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) 27,30.

Drug provocation tests can reproduce the hypersensitivity reactions of the clinical episode, but they are in general milder and have a shorter duration 27. Although they are dangerous procedures and potentially life-threatening, these tests are important to confirm drug hypersensitivity, and therefore non-hypersensitive patients would not need to avoid the related drugs in the future if the test were negative 5.

Intradermal and patch tests for non-immediate allergyIntradermal and patch tests are recommended for the routine screening of patients with suspected non-immediate allergy 23. The drug skin tests should be performed 6weeks to 6months after resolution of the drug reaction. Barbaud et al. 13 proposed a guideline for performing skin tests in order to standardise these procedures in cutaneous adverse drug reactions. According to the authors, skin testing should be performed with the commercialised drug whenever possible, and also with the pure active products and excipients. Systemic corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy must be interrupted for at least one month. For patients who have experienced severe reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, the drugs must be diluted first at 0.1 %; if negative then at 1.0 %; and if negative up to 10 % in patch tests 13. The intradermal tests are contraindicated in these patients. Healthy volunteers with or without previous exposure to the drug can be used as negative controls. The highest frequency of positive drug patches are related to p lactam antibiotics, especially amoxicillin; cotrimoxazole; corticosteroids; heparin derivatives; carbamazepine; diazepam; and pseudoephedrine 13. Delayed positive results in intradermal tests can be obtained in maculopapular rash, eczema, erythroderma or fixed drug reactions. The threshold of specificity has been determined for various drugs, such as p lactam antibiotics, erythromycin and spyramicin, and needs to be determined for other drugs, because of the risk of false positives in intradermal tests 13.

Basophil activation testThe CD63 molecule was discovered in the 1990s and since then it has been used as a basophil activation marker in flow cytometry. The technique, which is named basophil activation test (BAT), relies upon anti-IgE to characterize basophiles and anti-CD63 to assess activation of these cells 31,32. The molecule is expressed by different types of cells, e.g. basophiles, mast cells, macrophages and platelets. In the resting cells, CD63 is anchored in the basophilic granule and weakly expressed on the surface membrane; upon activation, its expression is upregulated, besides other molecules, such as CD45, CD203c 31.The BAT test allows the diagnosis of immediate drug allergy and pseudoallergy mainly for drugs that are not always detectable by CAP-IgE 33. The BAT test is more sensitive and specific than other in vitro diagnostic techniques in drug allergy 33, and is essentially complementary to skin tests and allergen-specific IgE determinations 34.

This technique has been proven to be a useful tool for assessment of the diagnosis of IgE-mediated allergies, including drug allergy 33. The upregulation of CD63 and CD203c has been observed in tests for pollen, food, drugs, natural rubber latex, and recombinant pollen allergens 31. Nevertheless, it suffers from some drawbacks. It depends on various factors, such as temperature, incubation time, a diluting buffer, type of allergen, and a positive control as anti-IgE 31. The density of IgE and IgE receptors may vary considerably among individuals and also among basophiles from the same individual. This may play a negative role, particularly in nonatopic individuals and when the number of activated basophiles is low 34. The necessity of anti-IgE as a positive control in CD63 testing is considered to be an important drawback, once some patients are non-responders; also, the results might be influenced by the intake of drugs, such as glucocorticosteroids, immunossuppressives, and immunomodulators 31. Moreover, IL-3 may be necessary for the priming of basophiles without up-regulating the activation markers, since in drug allergy it can occur that the drugs per se induce a low rate of basophil activation in the test 35.

Other alternative means of detecting basophiles have recently been identified, such as the CD203c marker, a neural cell surface differentiation antigen E-NPP3 (ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase), which is exclusively present on basophiles among blood cells, mast cells and progenitors. The CD 203c marker is upregulated in response to allergen-specific and anti-IgE-induced IgE cross-linking similar to CD63 32,34 and can be applied in flow-assisted allergy diagnosis to improve the sensitivity of the BAT technique, but multi-centre studies are necessary in order to make the technique useful for clinical routine 35.

In a study evaluating immediate reactions to p-lactam, the sensitivity of the BAT test was 50 % and its specificity 94 % 36. Torres et al. 37 also assessing reactions to these antibiotics, found similar results to BAT with a sensitivity of 48.6 % and specificity of 93 %; moreover, the BAT for cephalosporin was positive in 77 % of the patients, indicating that this test seems to be very promising for cephalosporin allergy. Nonetheless, studies in larger samples are required in order to validate the technique 38.

Gamboa et al. 39 found a specificity of 90 % and sensitivity of 60 % to 70 % in BAT for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The results with BAT are suggestive that when it is positive there would be no need to perform the provocation test. However, Malbran et al. 40 showed that diclofenac activates basophiles in sensitive individuals in a way that does not induce CD63 expression, suggesting that the BAT test may not be reliable for NSAID hypersensitivity.

Lymphocyte transformation testThe lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) is a test that assesses drug-specific T cells activation after in vitro stimulation with various concentrations of the culprit drug 41. It has several advantages as it is not harmful for the patient; it can be positive in drug reactions caused by different immunopathogenic mechanisms 42. Although it is thought to be a reliable test 41, it has been considered more as a research tool than for diagnostic purposes 15. There are several variables which can influence its performance: time of testing; influence of therapy as corticosteroids; stimulation index; reproducibility; sensitivity; and specificity 41,42. According to Kano et al. 41, the right time to perform the test depends on the type of reactions, within one week from the onset of the skin rashes in patients with maculopapular exanthema or Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, and 5 to 8weeks after the onset of skin rashes in patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug rash and eosinophilia with systemic symptoms.

Detection of cytokines as IL-5The IL-5 secretion cells can be analysed in vitro in culture supernatants from LTT after activation with specific drugs, and improve LTT sensitivity 43. According to Sachs et al. 44 the determination of drug-specific IL-5 secretion was more sensitive (92 %) than the LTT (75 %) and patch test (55 %) in patients with drug-induced maculopapular exanthemas. As Th1 and Th2 patterns occur together or not in drug allergy, and as IL-5 is a representative of the Th2 profile, the tests should include the determination of a cytokine representative of the Th1 pattern, as IFNγ.

Markers of T cell activation such as CD69Considering the several disadvantages of LTT, as mentioned above, the detection of surface markers, such as CD69 and CD25, which upregulate upon T cell activation after contact with a specific antigen, peptide or drug, can also be a promising alternative for diagnostic purposes 30. The test consists in culturing peripheral mononuclear cells with nontoxic concentrations of the culprit drug for 36 to 72h and submitting them to flow cytometry after the addition of fluorochrome-labelled anti-human CD69 monoclonal antibodies 30.

Beeler et al. 30 evaluating 15 drug-allergic, LTT positive patients, found a CD69 upregulation in both TCD4 cells and TCD8 cells after drug stimulation, except when the cells were cultivated with clavulanic acid, which induced an increase of CD4 T cells only. The test has shown a high specificity since non-allergic individuals showed no increase of CD69 detection of T cells cultivated with drugs. However, the authors demonstrated that clavulanic acid could induce CD69 upregulation without proliferation of non-allergic cells and that vancomycin promoted the proliferation of non-allergic cells without CD69 upregulation. Therefore, the authors 30 strongly suggest the necessity of an assay evaluation for every drug to be tested in non-allergic individuals.

ConclusionThe development of new tests and the validation of already developed techniques have been contributing enormously in the diagnosis of drug allergy. The diagnostic tests, together with a carefully detailed clinical history of the patient, physical examination and routine laboratorial parameters, are critical to identify the culprit drug, for the hypersensitivity drug reaction classification, and finally for taking a decision upon the treatment of patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This article is part of a project entitled “Incidence evaluation of allergy hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactamics through laboratorial investigation of patients exposed to the drug”, sponsored by MCT/CNPq/MS-SCTIEDECIT-DAF 54/2005, process 402509/2005-6.