Edited by: Andrea Gallioli

Fundació Puigvert

Marco Moschini

San Raffaele Hospital

Last update: June 2025

More infoFGFR3 mutations are among the most frequent genomic alterations in urothelial cancer (UC) being mainly associated with the luminal papillary (LumP) subtype. With the establishment of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors, the treatment of UC is now shifting more and more towards personalized medicine. A systematic review using Medline and scientific meeting records was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses guidelines to assess the potential role of FGFR inhibitors in combination with additional therapies for the management of UC. Ongoing trials were identified via a systematic search on ClinicalTrials.gov. A total of eleven full-text papers, ten congress abstracts, and 5 trials on ClinicalTrials.gov were identified. Following the BLC2001 and THOR study, erdafitinib is the only approved FGFR1-4 inhibitor for metastatic UC with susceptible FGFR2/3 alterations following platinum-based chemotherapy. According to the THOR data of cohort 2, erdafitinib should not be recommended in patients who are eligible for and have not received prior immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). One phase 3 trial is currently evaluating the intravesical device system (TAR210) in FGFR-altered intermediate non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (MoonRISe-1). Preclinical evidence suggests that combination-based approaches could be considered to improve the efficacy of FGFR inhibitors in patients with UC. Nine phase 1b/2 trials are focusing on the combination of FGFR inhibitors with ICIs, chemotherapy, or enfortumab vedotin. In metastatic disease, some preliminary analyses have reported promising results from these combinations (e.g. NORSE and FORT-2 trial). However, no phase 3 trial is terminated, so there is currently no level 1 evidence with long-term outcomes to support the combination of FGFR inhibitors with ICIs, chemotherapy, or targeted therapies. A better understanding of the different mechanisms of action to inhibit FGFR signaling pathways, optimal patient selection and treatment approaches is still needed.

Las mutaciones del FGFR3, asociadas principalmente al subtipo papilar luminal (LumP) se encuentran entre las alteraciones genómicas más comunes en el cáncer urotelial (CU)). Gracias al desarrollo de los inhibidores del FGFR (receptor del factor de crecimiento de fibroblastos), el tratamiento del CU se acerca cada vez más a la medicina personalizada. Se realizó una revisión sistemática utilizando Medline y publicaciones de congresos científicos según las directrices PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) para evaluar el papel potencial de los inhibidores del FGFR utilizados en combinación con otras terapias para el tratamiento del CU. Se llevó a cabo una búsqueda sistemática en ClinicalTrials.gov para identificar ensayos clínicos en curso. En total, once artículos a texto completo, diez resúmenes de congresos y cinco ensayos fueron identificados. Según los estudios BLC2001 y THOR, erdafitinib es el único inhibidor de FGFR1-4 aprobado para el CU metastásico con alteraciones susceptibles en FGFR2/3 tras quimioterapia basada en platino.

Según los datos correspondientes a la cohorte 2 del ensayo THOR, erdafitinib no debe recomendarse en pacientes aptos para recibir tratamiento con inhibidores de puntos de control inmunitario (ICI) y que no lo hayan recibido previamente. Actualmente, un ensayo de fase 3 está evaluando el sistema de administración intravesical (TAR210) en el cáncer de vejiga no músculo-invasor de riesgo intermedio con alteraciones del FGFR (MoonRISe-1). Los estudios preclínicos sugieren que podrían considerarse estrategias basadas en terapias combinadas para mejorar la eficacia de los inhibidores del FGFR en pacientes con CU. Nueve ensayos de fase 1b/2 están enfocados a evaluar el papel de los inhibidores del FGFR en combinación con ICI, quimioterapia o enfortumab vedotina. En el contexto de la enfermedad metastásica, estudios preliminares han revelado resultados prometedores de estas combinaciones (por ejemplo, los ensayos NORSE y FORT-2). Sin embargo, ningún ensayo de fase 3 ha finalizado, por lo que actualmente no existen datos de nivel 1 con resultados a largo plazo que respalden la combinación de inhibidores del FGFR con ICI, quimioterapia o terapias dirigidas. Aún se requiere un mejor entendimiento de los diferentes mecanismos de acción de los inhibidores de las vías de señalización del FGFR, la selección óptima de pacientes y los enfoques terapéuticos.

Bladder cancer is the 9th most common cancer worldwide, with more than 550,000 new cases diagnosed and more than 220,000 deaths globally each year.1 Men are at increased risk of bladder cancer and are affected 3–5 times more often than women, making it the sixth most common cancer in men worldwide.1,2 Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) accounts for 70–75% of all newly diagnosed cases of urothelial cancer, whereas 20% show a muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), and 5–10% present with primary metastatic disease.3 Survival varies greatly and depends on the tumor staging. While the 5-year survival rate for NMIBC is about 70%, it drops to 36% for MIBC and 6% for metastatic disease.4,5 The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors in 2017 has revolutionized the treatment of metastatic disease.6 With the establishment of targeted therapies such as antibody drug conjugates and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors, the treatment of bladder cancer is now shifting more and more towards personalized medicine.7,8

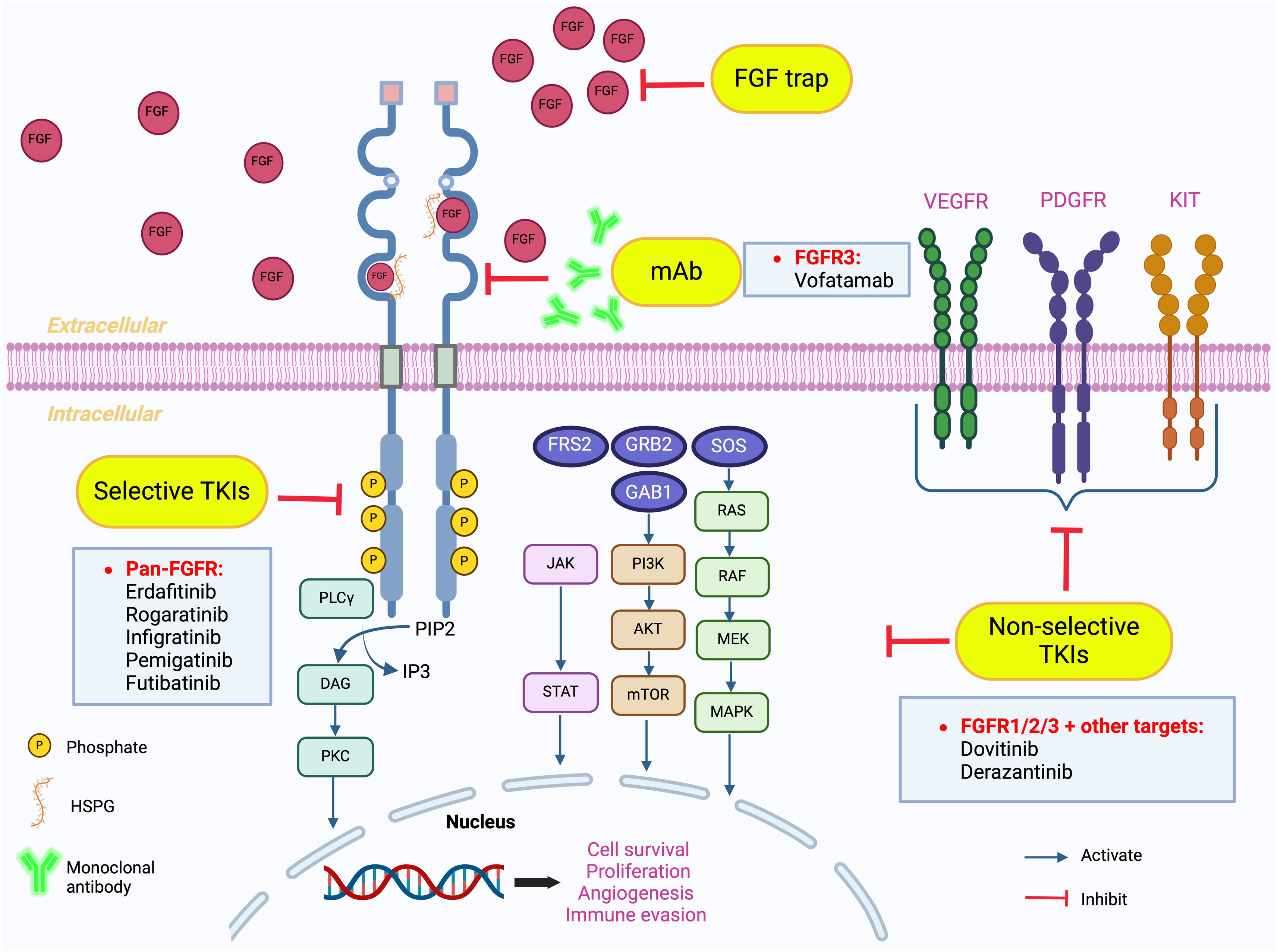

FGFR signaling pathway and inhibitionFGFRs are characterized as a subgroup of the tyrosine kinase receptors and are encoded by the genes FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, FGFR4, and FGFRL1.9 FGFRs consist of an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, an extracellular domain, and a transmembrane domain (TMD) connecting the two parts. The extracellular domain contains three immunoglobulin-like domains (D1, D2 and D3).10 Domains D2 and D3 are characterized as pockets for ligand binding, such as fibroblast growth factors (FGFs). D1 and D2 are important for binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which have a primary function in stabilization.11 When FGFs bind to the monomeric receptor, this will result in a conformational change in the receptor, dimerization of the FGFR, and phosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, leading to receptor activation.12 Upon activation, different downstream intracellular pathways will be stimulated. Phosphorylation of the FGFR activates FGFR substrate 2 (FRS2), which can, in turn, trigger the Ras-MAPK (rat sarcoma virus protein/mitogen-activated protein kinases) and PI3K-Akt-mTOR (phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathways via son of sevenless 1 (SOS1) and GRB2/GAB1 (growth factor receptor-bound 2/GRB2-associated binding protein 1) respectively.13–15 Besides this, phosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain can also lead to activation of PLCγ/PKC (phospholipase Cγ/protein kinase C) and JAK/STATs (Janus kinases/signal transducers and activators of transcription) pathways.16–19 Activating these pathways will result in the regulation of different cellular processes such as cell survival, apoptosis, migration, proliferation, immune evasion, and angiogenesis.18,20,21 An overview of the FGFR signaling pathway is given in Fig. 1.

FGFR signaling pathways and inhibition. FGFR binding to cognate ligands induces receptor dimerization, which can be stabilized by heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). Moreover, FGF-FGFR binding stimulates intracellular phosphorylation of receptor kinase domains such as FGFR substrate 2 (FRS2), phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ) and JAK, triggering four distinct downstream intracellular pathways including RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, JAK-STAT and PLCγ. Over-activation of these pathways regulates tumor cell metastasis, stimulates cell proliferation and differentiation, inhibits apoptosis, promotes tumor invasion and metastasis, and enhances tumor immune evasion. Inhibition of the FGF/FGFR pathway can occur at different levels. i) Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) or FGFR trap prevent FGF/FGFR binding in the extracellular domain, and small molecule TK inhibitors (TKIs) that the ATP-binding cleft of TK domains inside the cell. ii) Selective TKIs can specifically target the FGFR kinase domains. iii) Non-selective TKIs target several growth factor receptors (VEGFR, KIT and PDGFR). In bladder cancer, mAbs against FGFR3 (vofatamab), selective pan-FGFR TKIs (erdafitinib, rogaratinib, infigratinib, pemigatinib, futibatinib) and non-selective TKIs targeting FGFR 1/2/3 and other growth factor receptors (dovitinib, derazantinib) are currently being investigated in clinical studies.

As different members play a role in FGFR signaling, there are also different mechanisms to inhibit the pathway. Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and FGF trap ligands interfere by inhibiting the direct binding of FGF to FGFR. By targeting specific FGF ligands or receptor isoforms, mAbs such as vofatamab and bemarituzumab seem to give promising results in inhibiting the FGFR signaling pathways.14,22,23 FGF traps, such as FP-1039, are molecules that can bind to FGF in the extracellular environment, preventing FGF from binding to FGFR.14,24 Furthermore, the FGFR signaling can also be inhibited by acting on the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, using selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). This category might be the most studied one, with inhibitors such as erdafitinib, rogaratinib, infigratinib, pemigatinib and futibatinib.14 The pan-FGFR inhibitor erdafitinib, a clinically approved drug for urothelial carcinoma, can bind to the extracellular domain of the FGFR and with this block phosphorylases and inhibits the signal transduction pathways.25,26 Besides the selective TKIs, there are also non-selective TKIs, such as dovitinib and derazantinib, which are currently being studied in different clinical studies.14 Instead of directly inhibiting the FGFR signaling pathway, these non-selective TKIs target different other growth factor receptors such as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR).27 While this therapy might have an increased treatment efficacy, the disadvantage is the increased toxicity and inadequate bioactivity against FGFR as key signaling component.28,29Fig. 1 summarizes the different mechanisms of action to inhibit the FGFR signaling pathways.

FGF- and FGFR-coding gene alterations in urothelial cancerIn low-risk NMIBC, FGFR3 mutations are one of the most frequent alterations in bladder cancer, being associated with up to 70% of bladder cancer cases.30 However, somatic mutations of FGFR3 also belong to the most common genetic features of MIBC and were found in at least 15–20%.31,32 FGFR alterations are related to the molecular subtypes of NMIBC and MIBC. In the consensus molecular classification of MIBC by Kamoun and colleagues,33 FGFR3 genomic alterations (55%) were exclusively associated with the luminal papillary (LumP) subtype, accounting for 24% of MIBC samples. Focusing on the UROMOL2021 NMIBC transcriptomic classification,34 the frequent FGFR mutations were observed in class 1 (up to 54%) and class 3 (up to 94%). Importantly, it must be mentioned that most of tumors in the UROMOL2021 classes (93%) were classified as LumP, when classified according to the six molecular consensus classes of MIBC.34

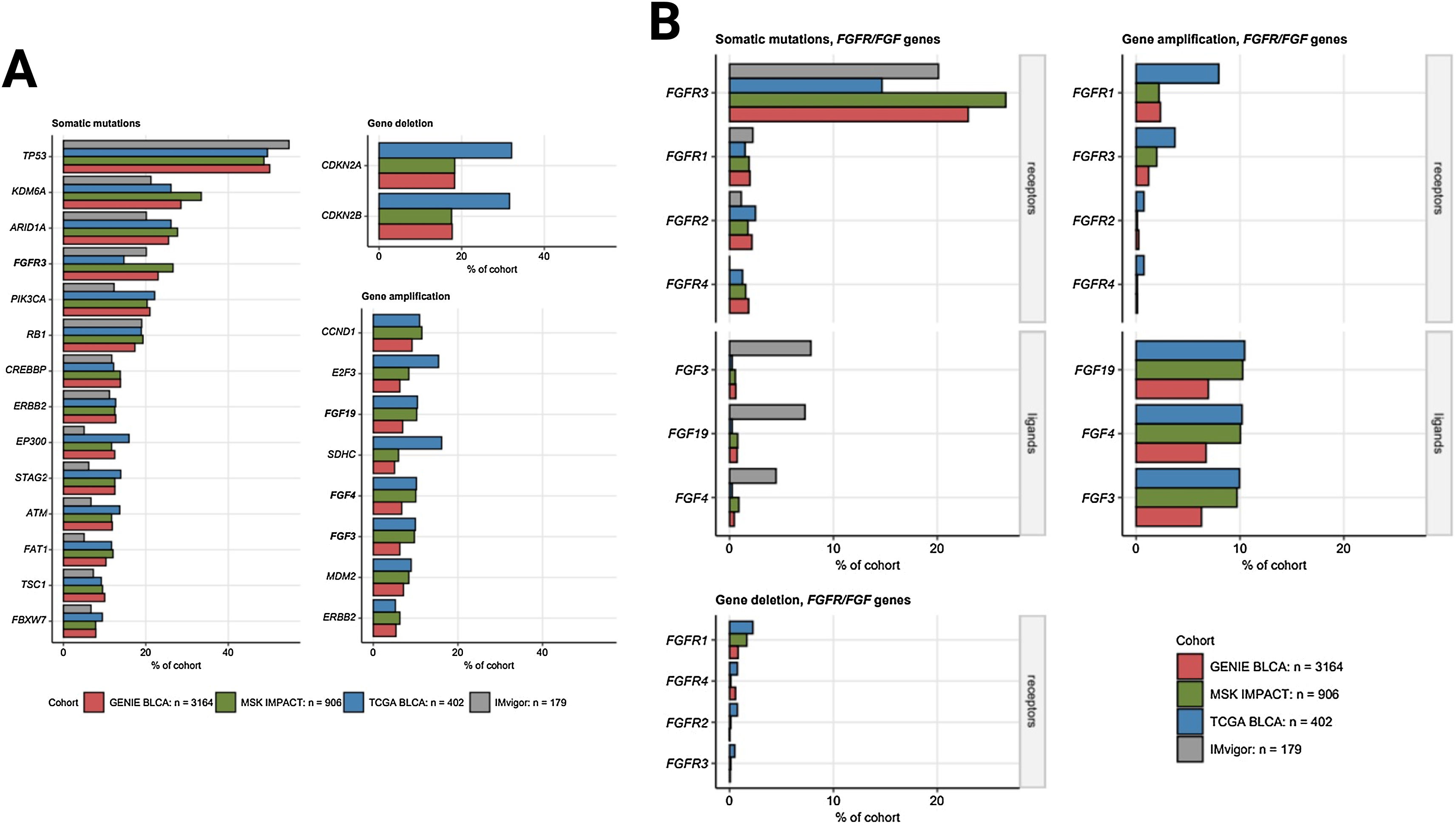

To get more insights about the effects of genetic alterations and modulation of expression of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes in addition to FGFR3 in urothelial cancer on tumor biology, therapy response, and clinical outcomes, we used four distinct collectives of urothelial carcinoma patients (GENIE BLCA,35 the MSK IMPACT collective,36 TCGA BLCA,37,38 and the IMvigor210 cohort39). The GENIE BLCA data sets were fetched from the cBioportal API with tools provided by the cbioportalR package (http://cbioportal.org) and formatted with in-house developed R scripts. Data sets for the TCGA BLCA cohort37,38 was fetched from the cBioportal repository with in-house developed scripts for n = 402 predominantly muscle-invasive urothelial cancer patients. The IMvigor data sets were obtained from the R package IMvigor210CoreBiologies. The data sets for the MSK impact study were downloaded from cBioportal and implemented in R with in-house developed scripts. JSON files with domain structures of FGFR1 (ID: P11362), FGFR2 (ID: P21802), FGFR3 (ID: P22607), and FGFR4 (ID: P22455) proteins were downloaded from UniProt and processed with the jsonlite package.40 A detailed description about the statistical and bioinformatic analysis is presented in the Supplementary data.

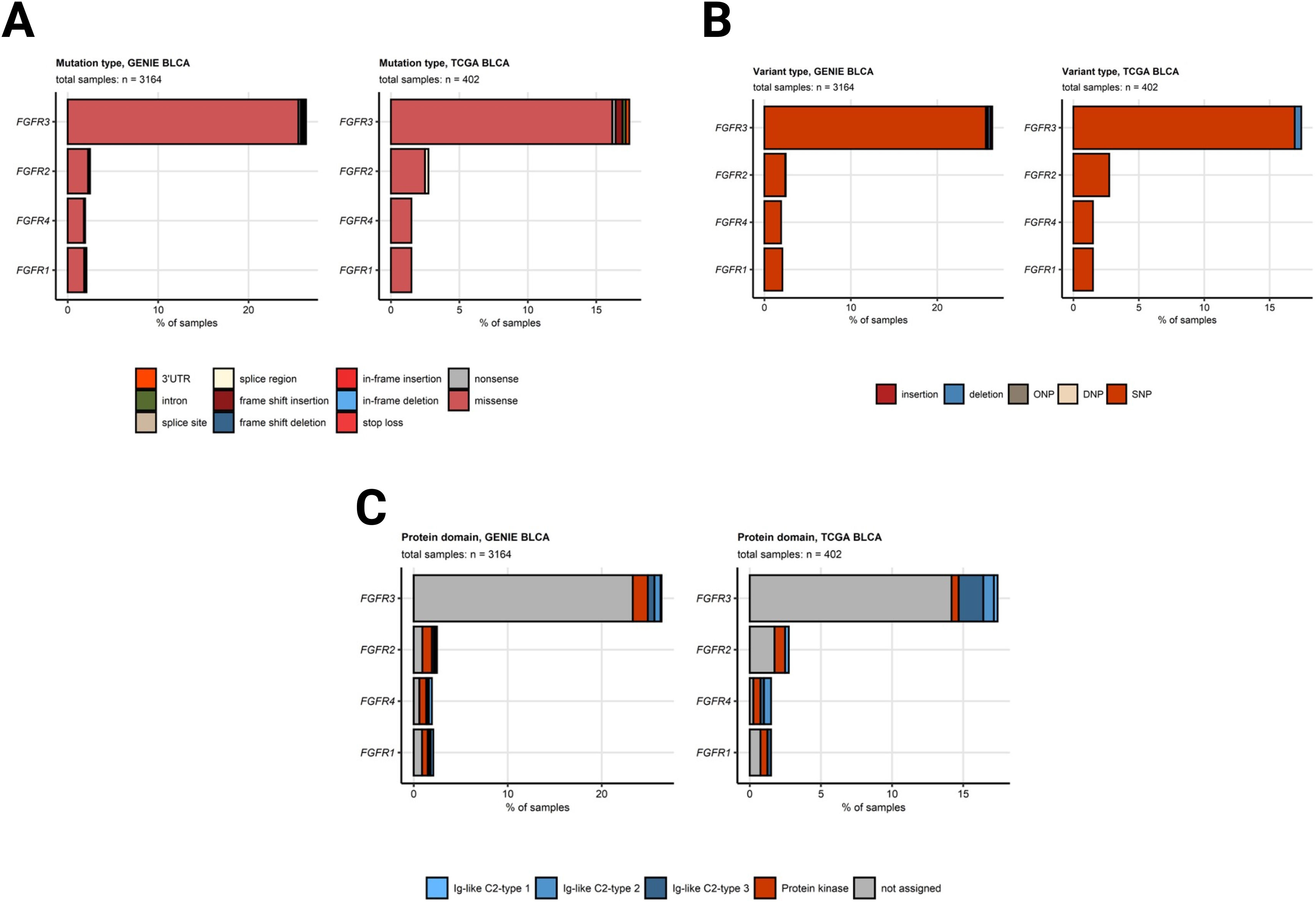

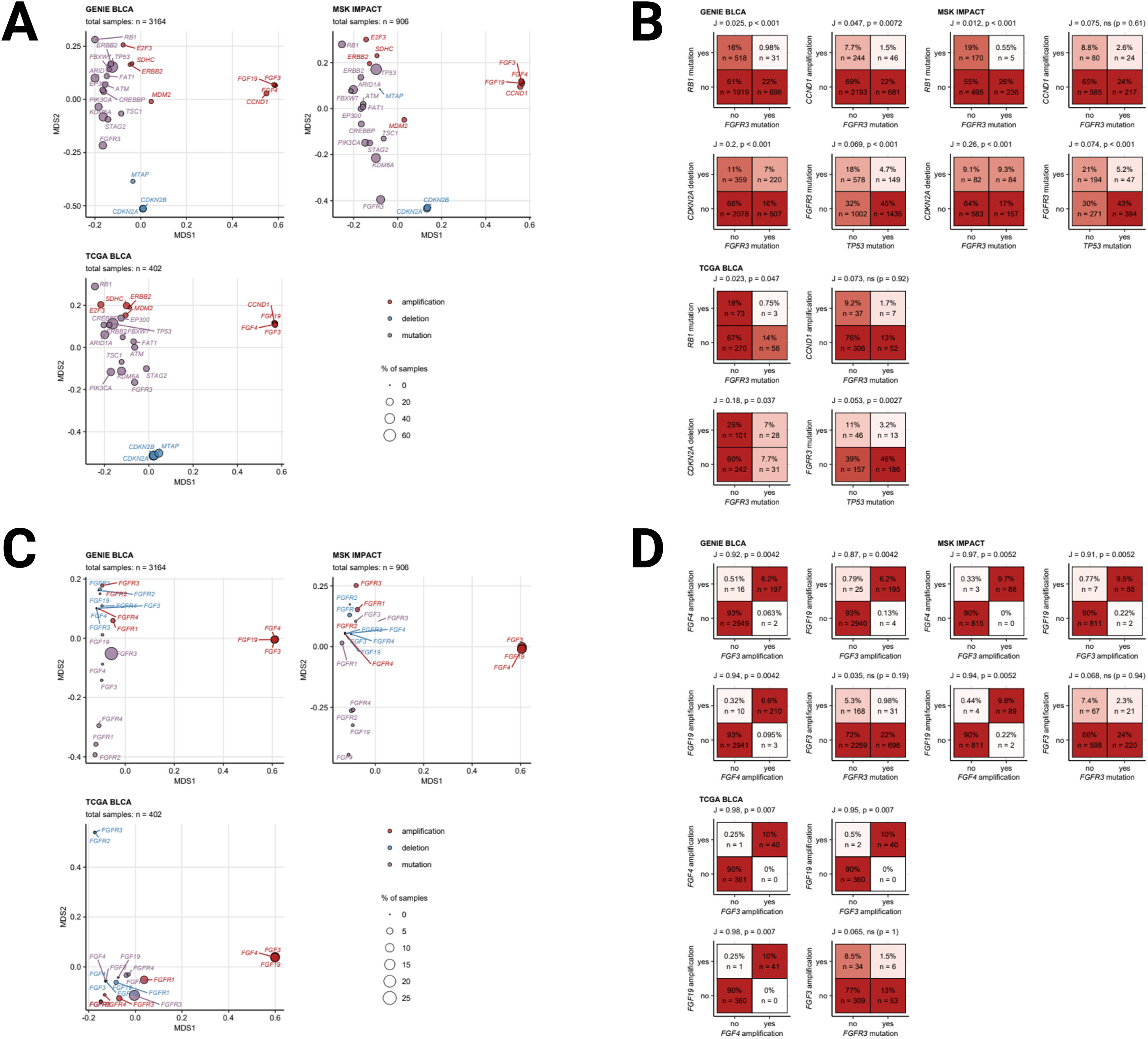

Somatic mutations of FGFR3 also belong to the most common genetic features of MIBC and were found in 15 to 27% of cancer samples. Somatic mutations of the other FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR4 receptor genes were less frequent (up to 2.5% of cancer samples). Amplifications of the FGF3, FGF4, and FGF19 genes in urothelial cancers result from multiplication of the 11q13 chromosome region, which also codes for an essential oncogene CCDN1. Amplifications of FGF3, FGF4, and FGF19 were detected in 6.3 to 10% of specimens, Fig. 2. A great majority of somatic mutations of FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4 was classified as missense mutations caused by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP). Particularly for FGFR3, the affected protein residues were frequently located apart from the Ig-like domains responsible for ligand binding and besides the kinase domains vital for activation of downstream signaling, Fig. 3. Co-occurrence and exclusivity of genetic features was investigated by analysis of pairwise Jacquard similarity coefficients for pairs of genetic alterations in urothelial cancer samples. Such analysis revealed little overlap between somatic mutations of FGFR3 and other common alterations such as TP53 and RB1 mutations, amplification of the 11q13 chromosome region hallmarked by copy number variants of FGF3/4/19 and CCND1, as well as deletion of the 9p21 chromosome region with the MTAP, CDKN2A, and CDKN2B genes, Fig. 4.

A) The most frequent somatic mutations and gene copy alterations in urothelial cancer. Percentages of somatic mutations, gene deletions and amplification present in at least 5% of cancers samples in all investigated cohorts (GENIE BLCA, MSK IMPACT, TCGA BLCA, and IMvigor, note: gene amplification and deletion data were not available for the IMvigor cohort) are presented in bar plots. Alterations affecting FGF- and FGFR-coding genes are highlighted with bold font. Numbers of analyzed cancer samples are indicated in the plot legend. B) Frequency of somatic mutations and copy number alterations of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes. Percentages of somatic mutations, deletions and amplifications of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes in the investigated cohort are presented in bar plots. Note that amplification and deletion data were not available for the IMvigor cohort. Numbers of analyzed cancer samples are indicated in the plot legend.

A) Frequency of somatic mutations in FGFR1/2/3/4 genes split by mutation type. B) Frequency of somatic mutations in FGFR1/2/3/4 genes split by variant type. C) Frequency of somatic mutations in FGFR1/2/3/4 genes split by protein domain. Mutations in FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4 genes in the GENIE BLCA and TCGA BLCA cohorts were classified by variant type. Their frequency was expressed as percentage of cancer samples and presented in stack plots. Numbers of analyzed cancer samples are displayed in the plot captions. SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism, DNP: di-nucleotide polymorphism; ONP: oligo-nucleotide polymorphism.

A) Co-occurrence of the most common genetic alterations in urothelial cancer. Co-occurrence of the most common genetic alterations in urothelial cancers (at least 5% of cancer samples) was investigated in the GENIE BLCA, MSK IMPACT, and TCGA BLCA cohorts by two-dimensional MDS (multi-dimensional scaling) of pairwise Jaccard’s distances. MDS results are visualized in scatter plots with single genetic alterations depicted as points. Point color codes for alteration type (somatic mutation, deletion, amplification), point size represents frequency of the alteration in the data set. Note that genetic features displayed in the plots close to each other are expected to co-occur in a high fraction of cancer samples. Total numbers of samples are indicated in the plot captions. B) Co-occurrence of selected genetic alterations in urothelial cancer. Co-occurrence of the most common genetic alterations in urothelial cancers (at least 5% of cancer samples) was investigated in the GENIE BLCA, MSK IMPACT, and TCGA BLCA cohorts by pairwise Jaccard’s similarity coefficients J. Statistical significance of co-occurrence was assessed by false discovery rate-adjusted bootstrap tests. Frequencies of samples with and without genetic alterations are visualized as heat maps of contingency tables for selected pairs of genetic features. Sample percentages and counts within the total sample sets are indicated in the heat map tiles. J and p values are presented in the plot captions. C) Co-occurrence of genetic alterations of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes in urothelial cancer. Co-occurrence of somatic mutations, deletions, and amplifications of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes was investigated in the GENIE BLCA, MSK IMPACT, and TCGA BLCA cohorts by two-dimensional MDS (multi-dimensional scaling) of pairwise Jaccard’s distances. MDS results are visualized in scatter plots with single genetic alterations depicted as points. Point color codes for alteration type (somatic mutation, deletion, amplification), point size represents frequency of the alteration in the data set. Note that genetic features displayed in the plots close to each other are expected to co-occur in a high fraction of cancer samples. Total numbers of samples are indicated in the plot captions. D) Co-occurrence of genetic alterations of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes in urothelial cancer. Co-occurrence of somatic mutations, deletions, and amplifications of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes was investigated in the GENIE BLCA, MSK IMPACT, and TCGA BLCA cohorts by two-dimensional MDS (multi-dimensional scaling) of pairwise Jaccard’s distances. MDS results are visualized in scatter plots with single genetic alterations depicted as points. Point color codes for alteration type (somatic mutation, deletion, amplification), point size represents frequency of the alteration in the data set. Note that genetic features displayed in the plots close to each other are expected to co-occur in a high fraction of cancer samples. Total numbers of samples are indicated in the plot captions.

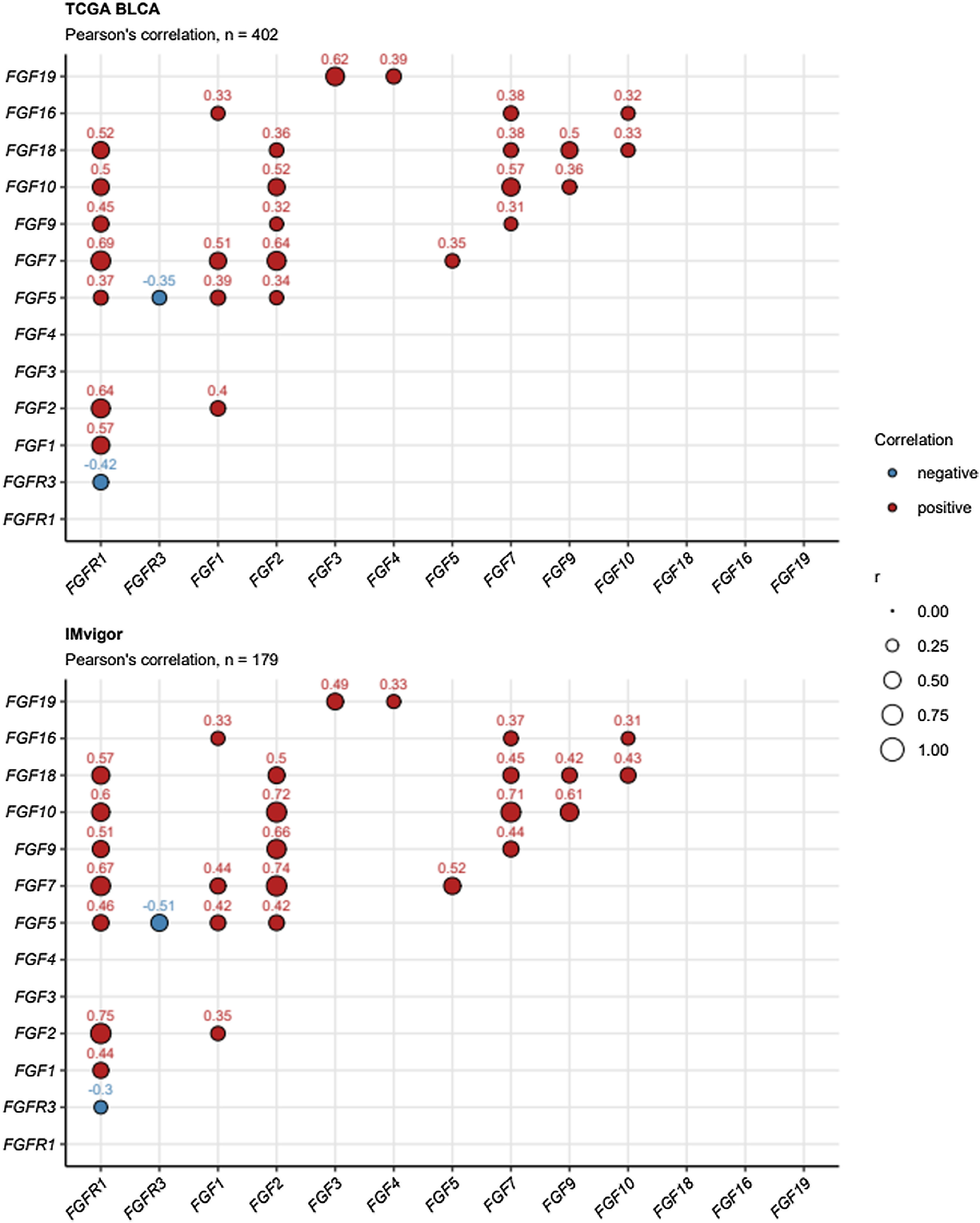

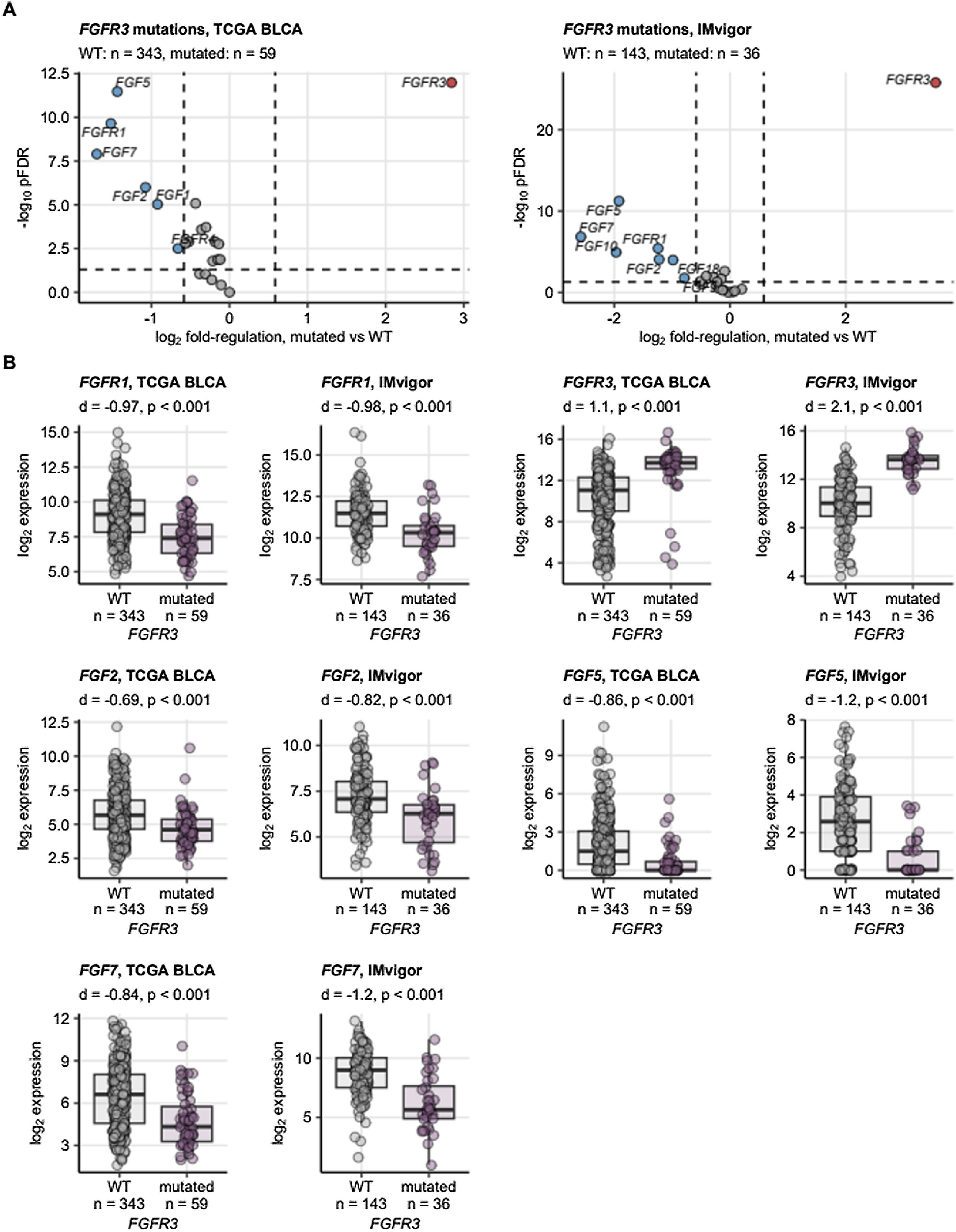

Interestingly, focusing on the co-regulation of expression of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes, FGFR1 and FGFR3 mRNA levels were found to be weakly but significantly negatively associated. In detail, increased expression of FGFR1 in the cancer tissue correlated significantly with upregulation of genes coding for multiple FGF ligands (FGF1, FGF2, FGF5, FGF7, FGF9, FGF10, and FGF18). However, this phenomenon was absent for FGFR3,Fig. 5. In a differential gene expression analysis of cancers with and without FGFR3 mutations, we observed that presence of FGFR3 mutations translated in significantly and strongly increased FGFR3 mRNA levels. By contrast, cancers with FGFR3 mutations had significantly lower expression of FGF2, FGF5, and FGF7, Fig. 6.

Correlation of mRNA levels of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes. Pairwise correlation of log2-transformed mRNA levels of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes was investigated in the TCGA BLCA and IMvigor cohorts by false discovery rate-adjusted Pearson’s test. Correlation coefficients r for significant gene pairs are depicted in bubble plots. Color of the points codes for correlation sign. Point size represents absolute values of r. Numbers of analyzed cancer samples are displayed in the plot captions.

Expression of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes in urothelial cancers stratified by presence of FGFR3 mutations. Differences in expression of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes between cancers with and without somatic mutations in the FGFR3 gene were assessed by two-tailed T test with Cohen’s d effect size metric in the TCGA BLCA and IMvigor. P values were corrected with the false discovery rate (FDR) method. Differentially regulated genes were identified by pFDR < 0.05 and at least 1.5 fold-regulation of gene expression in mutated samples as compared with WT specimens. (A) pFDR values and log2 fold-regulation estimates of gene expression in mutated vs. WT samples are presented in Volcano plots. Each point represents a single gene. Point color codes for significance and regulation sign, differentially regulated genes are labeled with their symbols. The significance and fold-regulation cutoffs of differential gene expression are depicted as dashed lines. Numbers of analyzed cancer samples are indicated in the plot caption. (B) log2-transformed mRNA levels for genes found to be differentially regulated in both cohorts are presented in box plots. Median expression values with interquartile ranges are depicted as boxes with whiskers spanning over 150% of the interquartile ranges. Single observations are visualized as points. Effect sizes and p values are displayed in the plot captions. Numbers of analyzed cancer samples are indicated in the X axes.

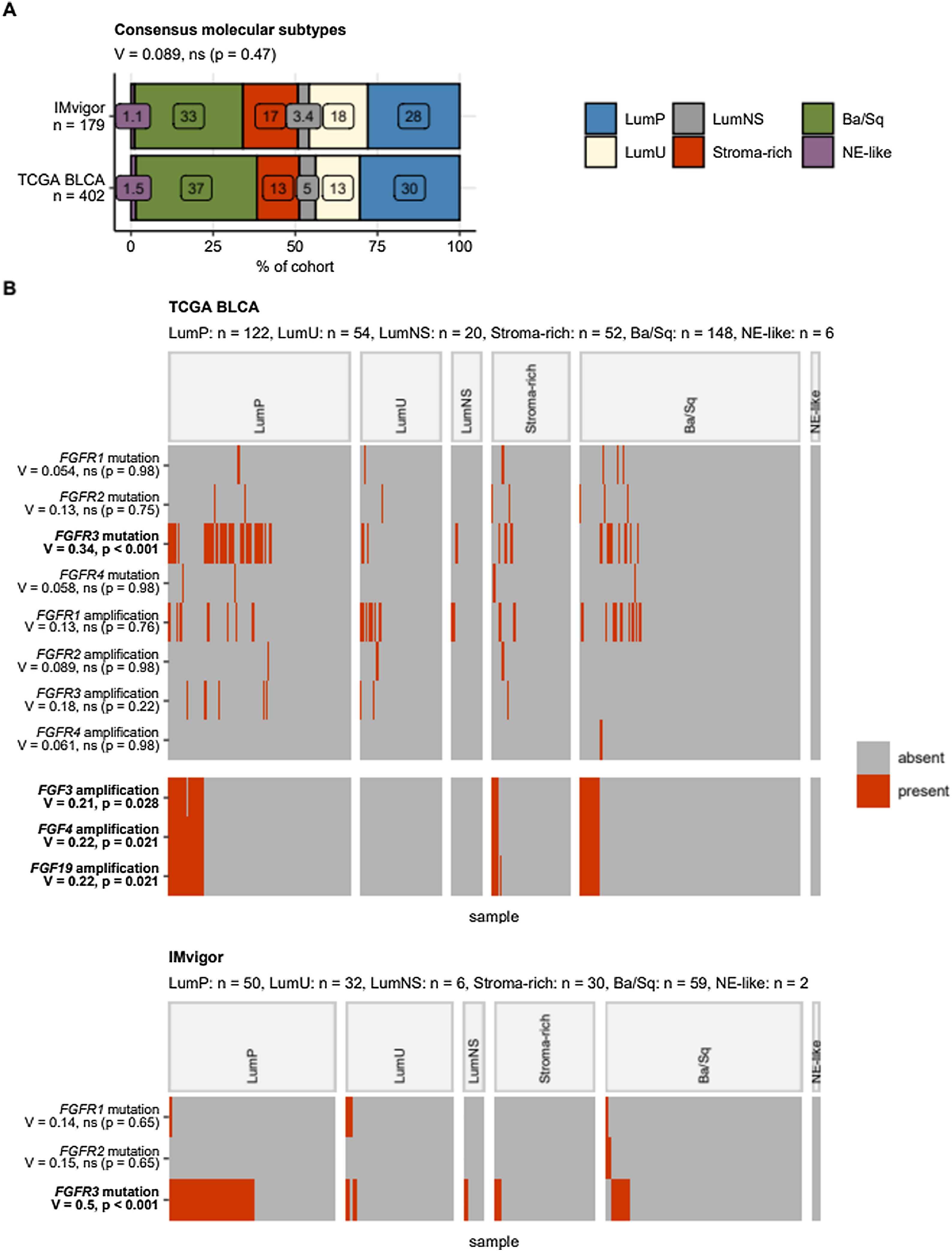

Focusing on the consensus molecular MIBC classes, FGFR3 mutated cancers were found to be significantly enriched in the LumP class (TCGA: 33%, IMvigor: 52% of specimens). In the TCGA cohort, amplifications of FGF3, FGF4, and FGF19 genes resulting from multiplication of the 11q13 chromosome region were found in LumP (18–19%), stroma-rich (9.6 to 12%), and basal/squamous-like cancers (8.8% of specimens), Fig. 7.

Alterations of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes in consensus molecular classes of urothelial cancers. Differences in frequency of somatic mutations and copy number variants of FGF- and FGFR-coding genes between the consensus molecular classes were assessed by test with Cramer’s V effect size statistic. P values were corrected for multiple testing with the false discovery rate method. Note that copy number variant information was not available for the IMvigor cohort. (A) Percentages of cancer samples in the consensus molecular classes were visualized in a stack plot. Statistical significance of difference in class distribution between the cohorts was assessed by test with Cramer’s V effect size statistic. The effect size and p value are shown in the plot caption. Total numbers of cancer samples are indicated in the Y axis. (B) Presence/absence of selected genetic alterations in the consensus molecular classes visualized in heat maps. Alteration names with effect sizes and p values of differences between the consensus classes are indicated in the Y axis. Significant effects are highlighted with bold font. Numbers of cancer samples in the consensus classes are displayed in the plot captions. LumP: luminal papillary; LumU: luminal genetically unstable; LumNS: luminal non-specified; Stroma-rich: luminal stroma-rich; Ba/Sq: basal/squamous-like; NE-like: neuroendocrine-like.

The LumP MIBCs, being associated with a strongly activated FGFR3 signature, harbor more frequent mutations of KDM6A and are characterized by younger patients (<60 yr), lower rate of extravesical disease and best survival rates when compared to the other molecular MIBC classes.33,34 Nevertheless, LumP tumors are characterized as “stroma and immune desert” cancers.41 Single cell RNA sequencing revealed a higher relative proportion of epithelial cells in FGFR3-mutated UC than the FGFR3-wildtype UC (41.9% vs. 4.3%, p < 0.001), whereas the proportions of immune cells and stromal cells in FGFR3-mutated UC were significantly lower than FGFR3-wildtype UC.42

The impact of FGFR3 mutation and genomic FGFR alterations on the prognosis of UC is still controversial and seems to depend on the therapy line and the therapeutic agents. While patients with FGFR3-mutated bladder cancer show favorable prognosis with low tumor grade and mostly papillary disease,43 FGFR3 mutations could result in lower response rates to platinum-based chemotherapy with a shorter recurrence-free survival in patients with locally advanced/metastatic UC (mUC)44 and a worse overall survival (OS) in comparison to FGFR-wildtype patients undergoing immunotherapy.42 Analyzing 4,035 UC samples with hybrid, capture-based comprehensive genomic profiling, FGFR3-altered UCs feature lower tumor mutational burden, lower programmed death-ligand 1 expression, and higher frequencies of genomic alterations in MDM2, being associated with a lack of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.45

A propensity score matched analysis of the phase 2 trial, IMvigor210, compared response to ICIs between patients with FGFR3-mutated and FGFR3-wildtype metastatic UC. In detail, FGFR3-mutated patients had worse OS in comparison to FGFR3-wildtype patients (HR = 2.11, 95% CI: 1.16 to 3.85; p = 0.015) receiving atezolizumab.42 One possible explanation for this is that FGFR3-mutated UC carried a stronger immunosuppressive microenvironment (less immune infiltration, low T cell cytotoxicity) compared with FGFR3-wildtype UC.42 On the other hand, data from the THOR trial on cohort 2 could not confirm these findings. Comparing Erdafitinib with pembrolizumab in anti-PD-(L1) naive patients and progressing after one prior treatment line, no difference in the primary endpoint OS was detected (10.9 vs. 11.1 mo, HR 1.18 (0.92–1.51)).46 Thus, FGFR3 mutation may not serve as conclusive predictive marker for lack of response to ICIs.41,47

Based on the short-lasting clinical benefits of FGFR3 inhibitors as monotherapy underline the importance of discovery of co-targets for future combinatorial studies.22 Because of their possible synergism, combination therapy involving ICIs and FGFR inhibitors has now been the subject of ongoing clinical research. As previously mentioned, downregulation of T-cell infiltration has been suggested to be associated with FGFR3 alterations, which are enriched in tumors exhibiting a luminal-papillary phenotype.48 The response rates to immunotherapy for LumP tumors are low (10 to 19%), which is also linked to poorer outcomes in patients with metastatic UC who have progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy.49,50 As FGFR inhibitors and immunotherapy may act synergistically, combination of both can increase the activation of T cells, and, thus, overcome resistance to ICIs.51

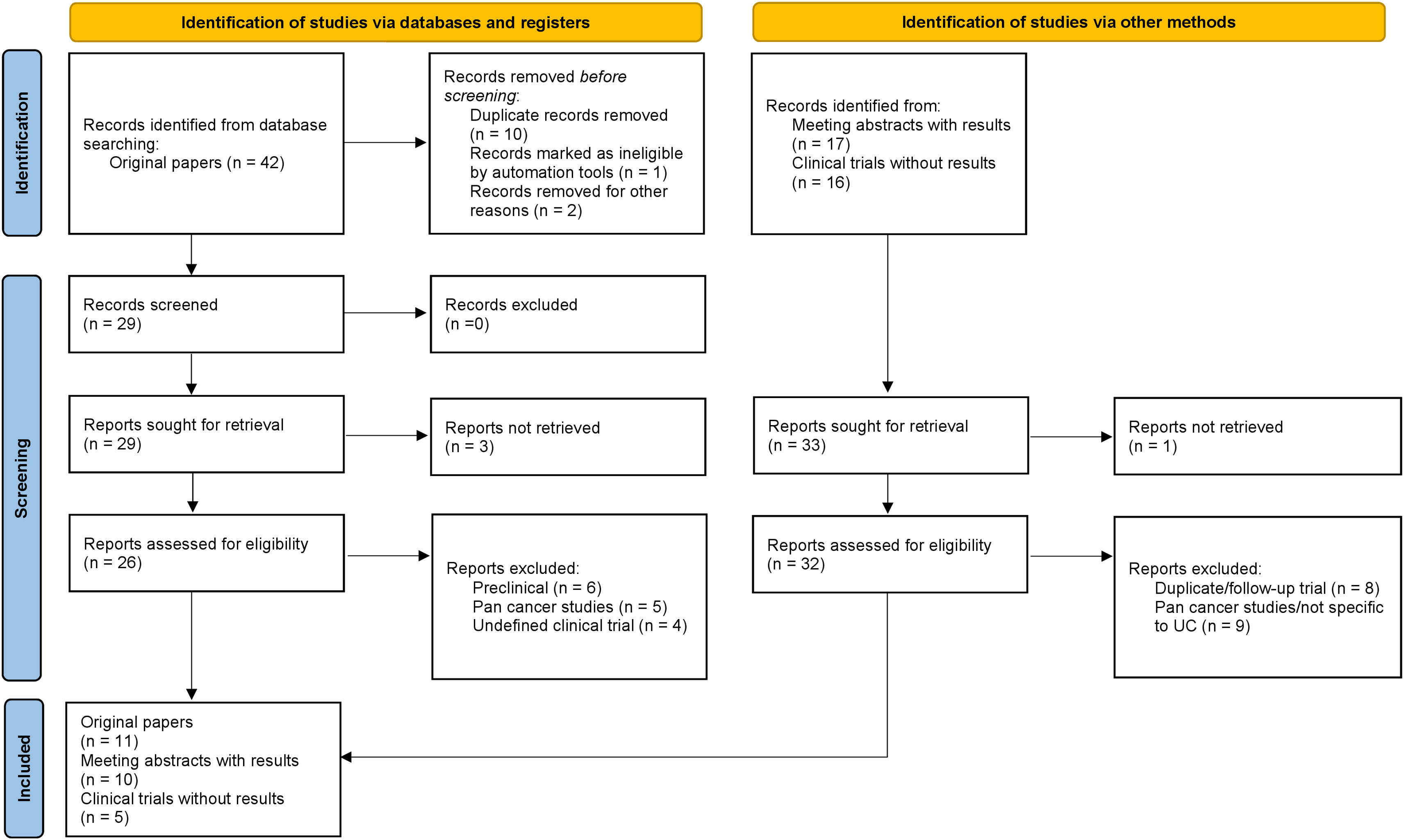

Acquisition of evidenceWe performed a systematic review of the literature on PubMed (all time to June 20, 2024) according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement,52Fig. 8. In addition, conference reports from the past five years from the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), ASCO Genitourinary Cancers (ASCO GU) and European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), up until the ASCO 2024 meeting were screened. Ongoing trials were identified via a systematic search on ClinicalTrials.gov. The inclusion criteria encompassed studies including patients with urothelial cancer who underwent treatment with any FGFR inhibitor as monotherapy or combination with immunotherapy or chemotherapy. Search results were restricted to studies published in English. Key search terms included “FGFR Inhibitors”, AND “urothelial cancer” AND “upper urinary tract” AND “clinical trial” OR respective aliases. The most recent reports of eligible studies were considered when directed searches were performed after the database search cutoff date. Studies including nonoriginal research, reviews or meta-analyses, correlative or preclinical science, not specific to urothelial cancer alone (pan cancer studies), retrospective or undefined clinical phase, trials not assessing FGFR-targeted therapy agents in NMIBC, MIBC or mUC, and duplicate/follow-up or prior reports were excluded. A total of four authors (R.P., N.vC., J.D.S., J.C.V.) were involved in the screening process and finally, five authors (R.P., N.vC., J.D.S, J.C.V. and A.G.) evaluated the included papers.

Synthesis of evidenceFeatures of studies included in the systematic reviewThe literature search identified a total of 75 records, resulting in a total of ten congress abstracts from ASCO, ASCO-GU or ESMO,53–62 eleven eligible full-text papers on pubmed8,46,63–71 and five clinical trials on ClinicalTrials.org (NCT06263153, NCT04003610, NCT04294277, NCT03914794, NCT06319820).

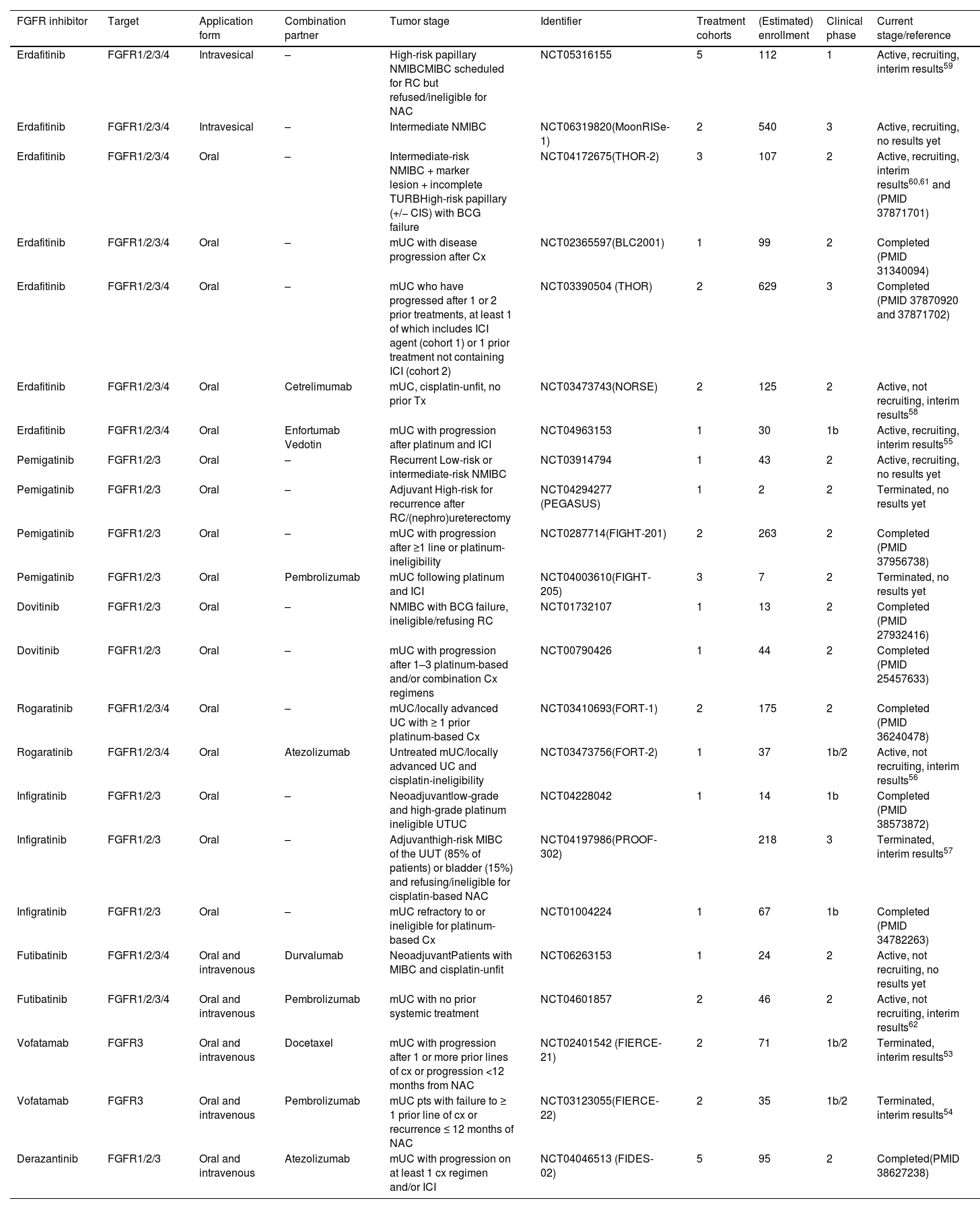

For FGFR inhibitors as monotherapy, ten full-text paper (two from one phase 3 trial, two phase 1b studies and six phase 2 trials)8,46,64–71 and four congress abstracts with interim results has been published57,59,60,61 and 3 studies (NCT04294277, NCT03914794, NCT06319820) are ongoing (one phase 3, two phase 2). For FGFR inhibitors in combination with ICIs, six of 7 studies are investigating this combination in metastatic disease. Of them, one trial has been published as full-text paper,63 two phase 2 studies are ongoing (NCT04003610, NCT06263153) and four congress abstracts with interim results has been published (two phase 1b/2 and two phase 2 trials).54,56,58,62 One phase 1b study is currently assessing the combination of FGFR inhibitor and enfortumab vedotin, presenting already interim results.55 One phase 1b trial is terminated to assess the combination of FGFR inhibitor plus chemotherapy (docetaxel) in mUC patients who progressed after one or more prior line of chemotherapy or < 12 months from neoadjuvant chemotherapy.53Table 1 presents detailed information for the above-described studies.

Overview of clinical studies with FGFR inhibitors as monotherapy or combining FGFR inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibitors or chemotherapy in urothelial cancer.

| FGFR inhibitor | Target | Application form | Combination partner | Tumor stage | Identifier | Treatment cohorts | (Estimated) enrollment | Clinical phase | Current stage/reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Intravesical | – | High-risk papillary NMIBCMIBC scheduled for RC but refused/ineligible for NAC | NCT05316155 | 5 | 112 | 1 | Active, recruiting, interim results59 |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Intravesical | – | Intermediate NMIBC | NCT06319820(MoonRISe-1) | 2 | 540 | 3 | Active, recruiting, no results yet |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | – | Intermediate-risk NMIBC + marker lesion + incomplete TURBHigh-risk papillary (+/− CIS) with BCG failure | NCT04172675(THOR-2) | 3 | 107 | 2 | Active, recruiting, interim results60,61 and (PMID 37871701) |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | – | mUC with disease progression after Cx | NCT02365597(BLC2001) | 1 | 99 | 2 | Completed (PMID 31340094) |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | – | mUC who have progressed after 1 or 2 prior treatments, at least 1 of which includes ICI agent (cohort 1) or 1 prior treatment not containing ICI (cohort 2) | NCT03390504 (THOR) | 2 | 629 | 3 | Completed (PMID 37870920 and 37871702) |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | Cetrelimumab | mUC, cisplatin-unfit, no prior Tx | NCT03473743(NORSE) | 2 | 125 | 2 | Active, not recruiting, interim results58 |

| Erdafitinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | Enfortumab Vedotin | mUC with progression after platinum and ICI | NCT04963153 | 1 | 30 | 1b | Active, recruiting, interim results55 |

| Pemigatinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | Recurrent Low-risk or intermediate-risk NMIBC | NCT03914794 | 1 | 43 | 2 | Active, recruiting, no results yet |

| Pemigatinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | Adjuvant High-risk for recurrence after RC/(nephro)ureterectomy | NCT04294277 (PEGASUS) | 1 | 2 | 2 | Terminated, no results yet |

| Pemigatinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | mUC with progression after ≥1 line or platinum-ineligibility | NCT0287714(FIGHT-201) | 2 | 263 | 2 | Completed (PMID 37956738) |

| Pemigatinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | Pembrolizumab | mUC following platinum and ICI | NCT04003610(FIGHT-205) | 3 | 7 | 2 | Terminated, no results yet |

| Dovitinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | NMIBC with BCG failure, ineligible/refusing RC | NCT01732107 | 1 | 13 | 2 | Completed (PMID 27932416) |

| Dovitinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | mUC with progression after 1–3 platinum-based and/or combination Cx regimens | NCT00790426 | 1 | 44 | 2 | Completed (PMID 25457633) |

| Rogaratinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | – | mUC/locally advanced UC with ≥ 1 prior platinum-based Cx | NCT03410693(FORT-1) | 2 | 175 | 2 | Completed (PMID 36240478) |

| Rogaratinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral | Atezolizumab | Untreated mUC/locally advanced UC and cisplatin-ineligibility | NCT03473756(FORT-2) | 1 | 37 | 1b/2 | Active, not recruiting, interim results56 |

| Infigratinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | Neoadjuvantlow-grade and high-grade platinum ineligible UTUC | NCT04228042 | 1 | 14 | 1b | Completed (PMID 38573872) |

| Infigratinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | Adjuvanthigh-risk MIBC of the UUT (85% of patients) or bladder (15%) and refusing/ineligible for cisplatin-based NAC | NCT04197986(PROOF-302) | 218 | 3 | Terminated, interim results57 | |

| Infigratinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral | – | mUC refractory to or ineligible for platinum-based Cx | NCT01004224 | 1 | 67 | 1b | Completed (PMID 34782263) |

| Futibatinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral and intravenous | Durvalumab | NeoadjuvantPatients with MIBC and cisplatin-unfit | NCT06263153 | 1 | 24 | 2 | Active, not recruiting, no results yet |

| Futibatinib | FGFR1/2/3/4 | Oral and intravenous | Pembrolizumab | mUC with no prior systemic treatment | NCT04601857 | 2 | 46 | 2 | Active, not recruiting, interim results62 |

| Vofatamab | FGFR3 | Oral and intravenous | Docetaxel | mUC with progression after 1 or more prior lines of cx or progression <12 months from NAC | NCT02401542 (FIERCE-21) | 2 | 71 | 1b/2 | Terminated, interim results53 |

| Vofatamab | FGFR3 | Oral and intravenous | Pembrolizumab | mUC pts with failure to ≥ 1 prior line of cx or recurrence ≤ 12 months of NAC | NCT03123055(FIERCE-22) | 2 | 35 | 1b/2 | Terminated, interim results54 |

| Derazantinib | FGFR1/2/3 | Oral and intravenous | Atezolizumab | mUC with progression on at least 1 cx regimen and/or ICI | NCT04046513 (FIDES-02) | 5 | 95 | 2 | Completed(PMID 38627238) |

TAR-210 is an intravesical delivery system designed to provide sustained, local release of erdafitinib into the bladder for 3 months while limiting systemic toxicities in patients with NMIBC or MIBC and select FGFR alterations. First results from an open-label, multicenter Phase 1 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of TAR-210 in NMIBC were presented at the ESMO 2023. In patients with Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG)-pretreated/unresponsive high-risk NMIBC (cohort 1), the recurrence-free rate was 82%. Moreover, 87% of patients with intermediate-risk NMIBC and visible target lesions prior to treatment (cohort 3) achieved a complete response. TAR-210 was also well tolerated with limited systemic toxicity. In detail, TAR-210-related grade ≥2 adverse events (AEs) and discontinuations were infrequent, with predominantly grade 1 urinary system AEs. These encouraging preliminary results support the initiation of phase 3 studies of TAR-210 in FGFR-altered NMIBC.59

The phase 3 MoonRISe-1 trial (NCT06319820) has recently started and is recruiting intermediate-risk NMIBC patients with susceptible FGFR alterations, comparing the disease-free survival as primary endpoint between TAR-210 vs. investigator’s choice of intravesical chemotherapy (gemcitabine or mitomycin C). In this study, all visible papillary tumors must be fully resected prior to randomization.

THOR-2 (NCT04172675) is a multicohort phase 2 study of erdafitinib, an oral selective pan-FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with NMIBC, including 3 distinct cohorts.

Cohort 1 enrolled 73 patients with recurrent, BCG-treated HR NMIBC (papillary disease only, no CIS) with FGFR alterations, comparing recurrence-free survival (RFS) between erdafitinib 6 mg/day and investigator’s choice of intravesical chemotherapy (gemcitabine or mitomycin C). During a median follow-up of 13.4 mo, median RFS was not reached for erdafitinib and was 11.6 months for intravesical chemotherapy. At the final analysis of the study, the RFS rate at 12 months was 77% for erdafitinib and 41% for intravesical chemotherapy. This observed RFS benefit for erdafitinib was consistent across tumor stage and prior BCG therapy (BCG-experienced vs. BCG-unresponsive). Nevertheless, the tolerability of oral erdafitinib was challenging as 28.6% of patients had AEs leading to treatment discontinuation.71

Cohort 2 is defined as patients with BCG-unresponsive high-risk NMIBC with FGFR3/2 alterations who presented with CIS, with or without a papillary tumor and who refused or were not eligible for radical cystectomy. All patients received continuous oral erdafitinib 6 mg once daily without up-titration in 28-day cycles. The first interim analysis showed a complete response (CR) rate of 100% at 3 months and 75% at 6 months over a median follow-up of 10 mo. Grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 40% leading to treatment discontinuation in 20%.60Cohort 3 includes patients with intermediate risk NMIBC with FGFR3/2 alterations, with complete endoscopic tumor resection except for a marker lesion (up to 5–10 mm). The primary endpoint was CR, defined as disappearance of the marker lesion without any new lesions. The CR rate for patients receiving erdafitinib 6 mg/day was 75% (6 of 11 patients). The most common treatment-related adverse events were hyperphosphatemia (n = 9), diarrhea (n = 6), dry mouth (n = 5), dry skin (n = 3), dysgeusia (n = 3), and constipation (n = 3).61

Metastatic diseasePatients with mUC and FGFR3 mutation or FGFR2/3 fusion who experienced disease progression after chemotherapy were included in the phase II BLC2001 trial (NCT02365597) of erdafitinib.70 Three-quarters of the 99 patients had stable disease, and the confirmed ORR was 40%. Only one of the 22 patients who had previously undergone immunotherapy had a response, but the response rate to erdafitinib in this subgroup was 59%. The median OS was 11.3 months (95% CI: 9.7–15.2) and the median PFS was 5.5 months (95% CI: 4.0–6.0) at a median follow-up of 24 mo. In 46% of patients, treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were grade 3 or higher. Hyponatremia (11%), stomatitis (10%), and asthenia (7%) were common AEs of ≥ grade 3.70

THOR (NCT03390504) is a confirmatory, randomized phase 3 study, with cohort 1 assessing whether erdafitinib provided a survival benefit vs. investigator’s choice of chemotherapy (docetaxel or vinflunine) in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer and susceptible FGFR3/2 alterations who progressed after 1 or 2 prior treatments, including checkpoint inhibitors. Among 266 patients, the median PFS (5.6 mo vs. 2.7 mo, p < 0.001) and OS (12.1 mo vs. 7.8 mo; p = 0.005) was significantly longer with erdafitinib than with chemotherapy. Treatment-related toxicity grade ≥ 3 was similar in the two groups. The most common treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or higher were palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (9.6%), stomatitis (8.1%), onycholysis (5.9%), and hyperphosphatemia (5.2%) in the erdafitinib group.8Cohort 2 of the THOR trial (NCT03390504) included 351 patients with select FGFR alterations, disease progression on one prior treatment, but who were anti-PD-(L)1-naive. Patients were randomized to receive erdafitinib 8 mg once daily with pharmacodynamically guided up-titration to 9 mg or pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was not met without any differences in the median OS (10.9 vs. 11.1 mo, HR 1.18 (0.92–1.51). Overall response rate was 40% and 21.6% and median duration of response was 4.3 and 14.4 months for erdafitinib and pembrolizumab, respectively. 64.7% and 50.9% of patients in the erdafitinib and pembrolizumab arms had ≥ 1 grade 3–4 adverse events.46

PemigatinibNon-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)Pemigatinib is an oral kinase inhibitor with a potent and selective FGFR1, 2, and 3 inhibitor activity.72 A phase II trial (NCT03914794) is examining pemigatinib in patients with NMIBC with recurrent low- or intermediate-risk tumors. Participants will receive pemigatinib for 4–6 weeks prior to standard of care TURBT. The primary endpoint will be CR as determined at TURBT.

AdjuvantPEGASUS (NCT04294277) is an open-label, single-arm, Phase II study, evaluating safety and efficacy of Pemigatinib as adjuvant therapy for molecularly selected, high-risk patients with urothelial carcinoma who have received radical surgery. Patients will receive Pemigatinib at a once-daily (QD) dose of 13.5 mg on a continuous schedule. Treatment will be continued until 12 mo, or until the evidence of disease relapse or onset of unacceptable toxicity. “High-risk” patients are defined as histological evidence of pT3-4 and/or pN1-3 urothelial cancer of the bladder or UUT after radical cystectomy/radical nephroureterectomy. This trial is currently terminated.

Metastatic diseaseThe FIGHT-201 trial (NCT02872714) is an open-label, single-arm, phase II study and reports the efficacy and safety of pemigatinib in previously treated, unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer with FGFR3 alterations. Patients were stratified according to their FGFR alterations. Cohort A included patients with FGFR3 mutations or fusions/rearrangements and cohort B patients with other FGF/FGFR alterations. Pemigatinib was given 13.5 mg once a day continuously or intermittently until unacceptable toxicity or progression. Among 260 patients, 107 patients showed FGFR3 mutations. In this group, the objective response rate (ORR) was similar regardless of whether it was administered continuously (23.9%) or intermittently (24.6%). On the contrary, pemigatinib had limited clinical efficacy among patients in cohort B. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were diarrhea (44.6%) and alopecia, stomatitis, and hyperphosphatemia (42.7% each).69

DovitinibNon-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC)Dovitinib (CHIR-258) is an orally active, potent multi-targeted tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor targeting FGFR1, 2 and 3. A phase 2 trial from the Hoosier Cancer Research Network GU12-157 evaluated the clinical efficacy of dovitinib 500 mg once daily (5 days on/2 days off) on q28d cycles in BCG-refractory NMIBC with FGFR3 mutations. The primary endpoint was not met with a 6-month CR rate of 8%. Dose reduction was necessary in 77% (n = 10). In summary, long-term administration of dovitinib was not feasible due to frequent treatment related grade 3/4 events (fatigue, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, stomatitis, hepatotoxicity).68

Metastatic diseaseA phase 2 trial (NCT00790426) included 44 patients with mUC who had progressed after one to three platinum-based and/or combination chemotherapy regimens. Patients received 500 mg dovitinib once daily on a 5-days-on/2-days-off schedule. The study did not meet its primary endpoint as the ORR was low, regardless of FGFR3 mutation status (0% in patients with mutant and 3.2% in patients with wild-type FGFR3 status).

RogaratinibMetastatic diseaseFORT-1 is a phase II/III, randomized, open-label trial including patients with FGFR1/3 mRNA-positive locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer who progressed after ≥ 1 prior platinum-containing regimen. Patients received rogaratinib (n = 87) or chemotherapy (docetaxel 75 mg/m2, paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, or vinflunine 320 mg/m2; n = 88). Enrollment was stopped before phase III could begin due to treatments’ comparable efficacy on the interim phase II analysis. ORR were 20.7% (rogaratinib) and 19.3% for chemotherapy. Median OS was 8.3 months (rogaratinib) and 9.8 months (chemotherapy). Focusing on FGFR3 alterations, those patients showed ORR of 52.4% with rogaratinib compared to 26.7% for chemotherapy. Thus, FGFR3 DNA alterations in association with FGFR1/3 mRNA overexpression might be a favourable marker for predicting response to rogaratinib.65

InfigratinibNeoadjuvantInfigratinib is a selective FGFR1–3 inhibitor with efficacy in advanced urothelial carcinoma with FGFR3 alterations. A phase 1b trial (NCT04228042) evaluated infigratinib as neoadjuvant treatment in 14 patients with localized UTUC undergoing ureteroscopy or nephroureterectomy.66 Once-daily infigratinib 125 mg × 21 days (28-day cycle) was given for 2 cycles. Six (66.7%) out of 9 patients with FGFR3 alterations showed responses with a median tumor size reduction of 67%. Renal preservation was enabled in 3 out of 5 patients with responses initially planned for radical surgery. Median follow-up in responders was 24.7 mo.66

AdjuvantThe PROOF-302 study is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT04197986) including post-surgical high-risk MIBC of the upper urinary tract (85% of patients) or bladder (15%) with susceptible FGFR3 alterations and refusing/ineligible for cisplatin-based (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients receive oral infigratinib 125 mg or placebo daily on day 1–21 of a 28-day cycle until progression, toxicity or death. Genomic analysis about the prevalence of FGFR3 alterations in primary MIBC tissue was presented at ASCO 2023.57 Although FGFR3 genomic alterations occur with a significantly higher frequency in UTUC (up to 70%),73 FGFR3 alterations were noted in only 19% out of 617 patients screened for PROOF-302 : 30% of upper tract urothelial carcinoma, 13% of bladder urothelial carcinoma, and 9% of unknown tumor site. Thus, the trial was stopped early by the sponsor.57

Metastatic diseaseA phase 1b trial (NCT01004224)64 enrolled 67 patients who had mUC and were refractory to or ineligible for platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients received infigratinib 125 mg orally daily (3 weeks on/1 week off). The overall ORR was 25.4% and disease-control rate was 64.2%, respectively. Infigratinib showed notable efficacy in mUC patients regardless of lines of therapy. The ORR was 30.8% in the first-line setting (n = 13), and 24.1% for ≥2 lines of therapy.

The most common grade 3/4 treatment-emergent AEs were hyperlipasemia (10.4%), anemia (7.5%) and hyperphosphatemia (7.5%).64

CombinationsFutibatinib + durvalumabNeoadjuvantA Phase II trial of futibatinib in combination with durvalumab (NCT06263153) administered to cisplatin-unfit patients with MIBC before radical cystectomy is planned, but not yet recruiting. Patients will receive futibatinib orally once daily (day 1–28) and durvalumab on day 1 of each cycle. Treatment repeats every 28 days for up to 3 cycles prior to radical cystectomy.

Erdafitinib + cetrelimumabMetastatic diseaseThe phase 1b/2 NORSE trial,58 evaluates erdafitinib plus cetrelimumab in the first line setting of cisplatin-unfit metastatic patients with susceptible FGFR alterations (NCT03473743). Eighty-seven Patients were randomized 1:1 to once daily erdafitinib 8 mg (with up-titration to 9 mg) or erdafitinib 8 mg + cetrelimumab 240 mg every 2 weeks at cycles 1–4 and 480 mg every 4 weeks thereafter. The objective response rate for erdafitinib + cetrelimumab was 54.5% (CR 13.6%) and 44.2% (CR 2.3%) for erdafitinib alone. The 12 months-OS rate was 68% for erdafitinib + cetrelimumab and 56% for erdafitinib alone. Grade ≥3 treatment-related AEs occurred in 45.5% (erdafitinib + cetrelimumab) and 46.5% (erdafitinib) of patients. The most common treatment-emergent AEs (any grade) were hyperphosphatemia (68.9 vs. 83.7%), stomatitis (59.1 vs. 72.1%) and diarrhea (45.5 vs. 48.8%) for erdafitinib + cetrelimumab and erdafitinib alone.58

Pemigatinib + pembrolizumabMetastatic diseaseFIGHT-205 is a randomized, open-label, phase 2 study assessing the efficacy and safety of pemigatinib + pembrolizumab vs. pemigatinib alone vs. standard of care (Gemcitabin/carboplatin or pembrolizumab alone) in cisplatin-unfit, therapy-naive, metastatic patients with FGFR3 mutation/rearrangement.74 Pemigatinib titration to 18 mg starting at cycle 2 is required for all patients without hyperphosphatemia (serum PO4 >5.5 mg/dL) and grade ≥2 treatment-related AEs during cycle 1.74

Rogaratinib + atezolizumabMetastatic diseaseFORT-2 (NCT03473756) is a phase 1b/2 trial assessing clinical efficacy and tolerability of rogaratinib (600 mg twice a day) + atezolizumab (1200 mg every 3 weeks) in therapy-naive, cisplatin-unfit, FGFR-positive metastatic urothelial cancer patients.56 The disease control rate was high with 83% (CR 13%, PR 42% and 29% SD). The ORR was even high with 56% in patients with negative PD-L1 expression and FGFR3 mRNA overexpression without mutation. Therapy-related adverse events led to interruption/reduction/discontinuation of rogaratinib in 69%/46%/19% of patients. Importantly, rogaratinib-related adverse events were hyperphosphatemia in 15 pts (58%) and retinal pigment epithelium detachment in 1 patient (4%).56

Derazantinib +/− atezolizumabMetastatic diseaseThe phase 2 FIDES-02 (NCT04046513) trial evaluated the efficacy of derazantinib, a FGFR1-3 kinase inhibitor, as a single-agent or in combination with atezolizumab for patients with metastatic urothelial cancer harboring FGFR1-3 genetic alterations. However, first data were reported at the ASCO 2023 showing that derazantinib monotherapy did not meet its primary endpoint (ORR of 8%, median PFS 2.1 months and OS 6.6 months), thus not supporting its continued clinical development in metastatic urothelial cancer. However, toxicity was well manageable with low rates of treatment-related toxicities such as retinal disorders (16%), nail toxicity (4%) and stomatitis (4%).63

Vofatamab +/− docetaxelMetastatic diseaseFIERCE-21 is a phase 1b/2 study (NCT02401542) designed to evaluate vofatamab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against FGFR3 blocking the activation of the wildtype and genetically activated receptor, as a monotherapy or in combination with docetaxel.53 The study included metastatic patients with progression after one or more prior chemotherapies. Among 55 patients, the treatment was well tolerated with a low frequency of grade 3 treatment-related adverse events (1.8%). Adverse events occurring in ≥5% patients were asthenia (19%), diarrhea (9.5%), flushing 14%, chills (9.5%), hypotension (9.5%), decreased appetite (19%) and creatinine increased (9.5%). However, ORR has been confirmed in only 7 (12.5%) patients including those receiving both monotherapy and combination with docetaxel. 53

Vofatamab +/− pembrolizumabMetastatic diseaseFIERCE-22 (NCT03123055) was a phase 1b/2 study designed to evaluate vofatamab monotherapy followed in combination with pembrolizumab in metastatic patients who progressed after ≥ 1 line of chemotherapy but received no prior immune checkpoint inhibitors.54 Among 28 patients, the ORR was 29.6% and the median PFS was 4.7 months after a median follow-up of 7.5 months. 32% (n = 9) are still under treatment and are in long-term survival follow-up. Most common treatment-related adverse events >20% of patients were diarrhea, fatigue, anemia and pyrexia.54

Erdafitinib + enfortumab vedotin (EV)Metastatic diseaseA Phase 1b trial (NCT04963153) of erdafitinib combined with EV following platinum and immune checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic urothelial carcinoma with FGFR2/3 genetic alterations is currently ongoing.55 This dose escalation phase aims to identify the maximum tolerable dose and recommended phase 2 dose of enfortumab vedotin at 1 mg/kg and 1.25 mg/kg in combination with erdafitinib at 8 mg once a day. Among 8 patients, grade 3 treatment-related adverse events included hand foot syndrome (50%), anemia (17%), rash (17%), anorexia (17%) and paronychia (17%). All eight patients had partial remission as best response. Dose escalation is ongoing to identify the maximum tolerable dose and the recommended dose for expansion of the study.55

ConclusionsLumP tumors, typically characterized by FGFR3 mutations, show a “stromal and immune desert” with epithelial signatures and a strong immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, hypothesizing a low response to ICIs alone. Because of the possible synergism between ICIs and FGFR inhibitors, combination therapy has now been the subject of ongoing clinical research. Thus, FGFR inhibitors are currently being investigated not only as monotherapy but also in combination with ICIs, chemotherapy or antibody-drug conjugates in numerous studies from non-muscle invasive to metastatic disease.

None.