Maternity rates in women with schizophrenia have tripled in the past decades, with a current percentage similar to the general population (50–60%). However, mothers with schizophrenia present higher rates of single marital status, and social dysfunction than the general population. In addition, the incidence of unplanned pregnancy, abortions, miscarriages and obstetric complications is higher.

This study aimed to describe variables related to maternity in this population.

MethodsOne-hundred and ninety-two outpatient women diagnosed with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders were included (DSM-IV-TR criteria) in a two-site study. Psychosocial risk factors, demographic variables and clinical features were recorded in the same visit. Non-parametric tests were used in order to describe variables for likelihood offspring in psychotic women.

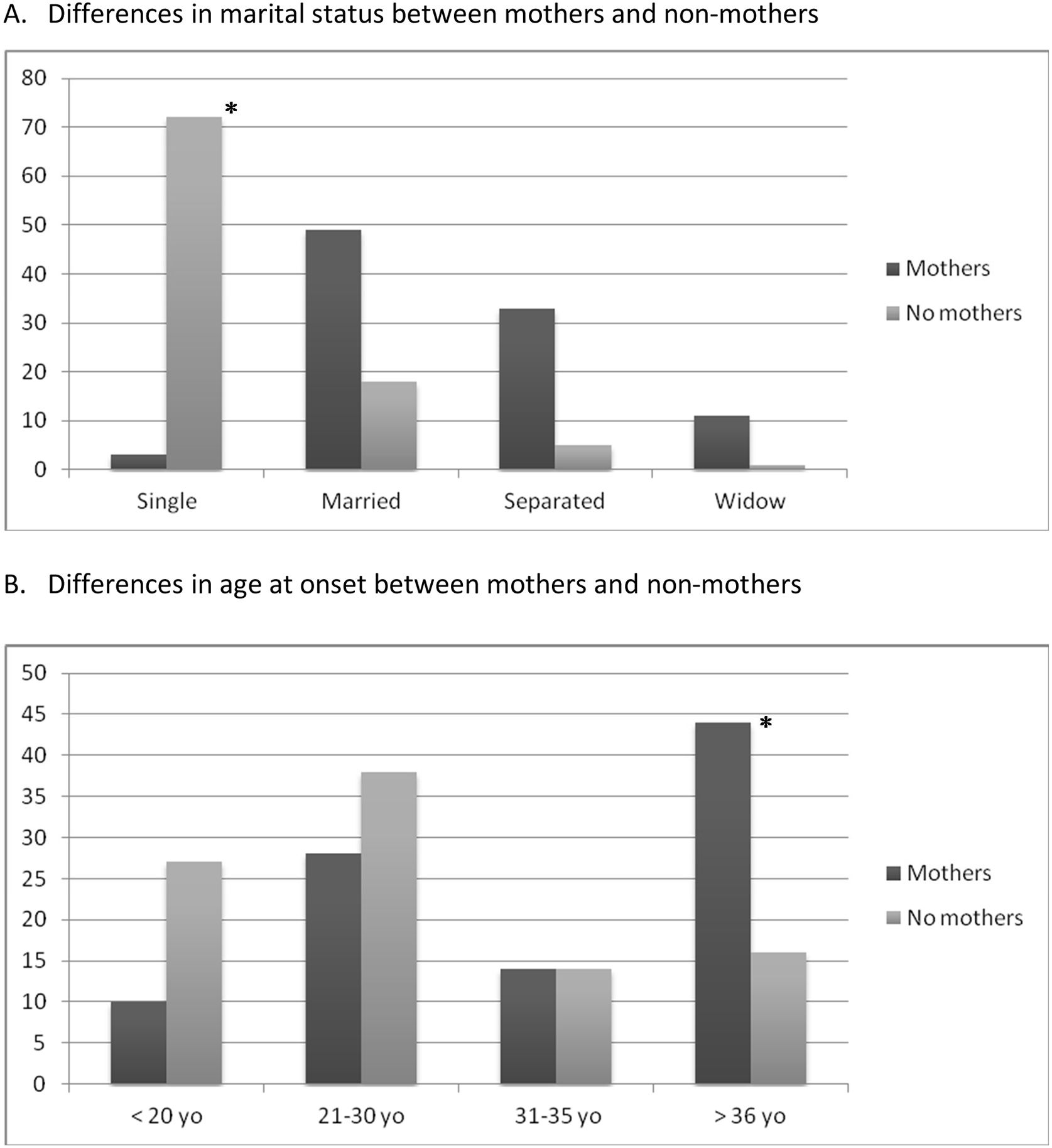

ResultsOne-hundred and forty-seven (76.6%) women suffered from schizophrenia and 45 (23.4%) schizoaffective disorder. Psychotic mothers used to be married/having a partner and presented a later onset of the illness (over 36 years old) compared to non-mothers. In addition, mothers generally presented pregnancy before the onset of illness. Regarding obstetric complications, around the 80% of the sample presented at least one obstetric complication. Although desire or wish of pregnancy was reported in 66.3% of the mothers, rates of planned pregnancy were 25% and only the 47.9% were currently taking care of their children with their husband/partner.

ConclusionMaternity rate is high in this population. This study highlights the need to promote reproductive health care for women with mental disorders and to consider their reproductive life plan.

Later onset of disease and being married are potential predictors of maternity in our sample of women with a schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders while only the half were caring their children at the moment of the evaluation.

Recent studies have highlighted the relevance of the global burden of disease attributed to schizophrenia when planning clinical services in severe mental illness.1 A recent systematic review explored the prevalence, incidence and excess of mortality in patients with schizophrenia, and found no sex differences in prevalence, even across countries and regions.1

Although this lack of gender differences in global burden of disease, women with schizophrenia show sex-specific health needs according to the particular stages of life.2 For instance, recent works have pointed out that women with schizophrenia differ in health needs in reproductive and post-reproductive stages. Contraception practices have been also discussed in these populations3 and pregnancy and postpartum periods have been considered periods of high vulnerability in schizophrenia women.

Although female patients suffering from schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders have been considered to be at risk of infertility, and have shown a lower probability of having children,4–8 maternity rates in women with schizophrenia have tripled in the past decades, showing at present a similar percentage than the general population (50–60%).7,9–12 In fact, a birth cohort study from Finland reported that women with this diagnosis are parents almost as often as are healthy women.13 Although schizophrenia has a relatively stable epidemiological profile throughout different countries, issues related to marriage and fecundity are both subjected to the influence of biological and socio-cultural factors.4,14–16

Other psychosocial studies have supported the notion that mothers diagnosed with schizophrenia are more frequently single, and show lower social and personal functioning than mothers from the general population, which might influence their maternal role. In fact, dealing with psychotic symptoms and meeting parental role obligations places immense pressure on people with severe mental illnesses17,18 influencing on their bonding skills.19,20 In consequence, it has been seen how women with a severe mental are more likely to have involvement with the child welfare system or experience out-of home placement of a child.21

Furthermore, in relation to pregnancy outcomes, patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders are at risk of a wide range of adverse events in pregnancy and in the postpartum period.22 Thus, childbirth has been associated with the emergence of psychotic symptoms or the occurrence of psychotic disorders, both leading to increased risk of admission during the first postpartum month.23 On the other hand, within previously diagnosed psychotic women, pregnancy has also been related with treatment discontinuation.24 Also, the incidence of unplanned pregnancy, abortions, miscarriage, adverse foetal outcomes and obstetric complications is higher among these women10,25 when compared to healthy mothers. Both lines of evidence might be in mind of health care professionals when helping on planning a future pregnancy on psychotic women.

Despite all the reported evidence, there is a scarcity of prospective studies exploring prenatal outcomes and their impact on childcare and parenting in women with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. It is still unknown the social or therapeutic interventions that may be effective to ensure the well-being of this particular population and there is also few existing data focusing on the experiences and needs of mothers with schizophrenia. From the social point of view, obtaining accurate data from these women can help to better establish preventive measures, improve childcare or parenting, and improve the assessment of needs and the efficacy of family planning programmes.26,27

In the present study, we aimed to explore variables related to pregnancy/maternity in women diagnosed with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Material and methodsParticipants and study designOne hundred ninety-two women diagnosed with schizophrenia and related disorders, and schizoaffective disorders were included in a two-site, outpatient, naturalistic observational study. The study was conducted in two different psychiatric outpatient clinics from the metropolitan area of Barcelona, the Department of Mental Health at the Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa and the Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit (BCSU) at the Hospital Clinic (Barcelona).

Inclusion criteria were: (1) female patients suffering from schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria, (2) age 19–80 years, (3) regular outpatient clinical appointments during the study period. Patients with other psychiatric diagnosis were excluded from the study.

We included a clinical sample of patients with schizophrenia and related disorders who were consecutively attended in both outpatient clinics. The subgroup of mothers with schizophrenia was compared with a clinical group of non-mothers with the same diagnoses. The final group comprised both subgroups (mothers and non-mothers) and represented a balanced total sample.

Outcomes and data collectionStudy data was recorded throughout a semi-structured questionnaire designed for the current study purposes.

Descriptive data for the entire female sample was collected, which included socio-demographic data (age, marital status, educational level, cohabitation and employment status), psychiatric diagnoses and age of psychiatric onset was obtained. The age at onset of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder was considered as the age when the productive psychotic symptoms of the disease appeared. According to this definition, patients were grouped into four groups: those with onset before 20 years old, from 21 to 30 years, from 31 to 35 years, and those with onset after 36 years old.

The parity and obstetric collected information of those that were mothers included: motherhood before the onset of illness, presence of a obstetric complication (during pregnancy, as well as at the perinatal period), prior elective abortions, miscarriages, spontaneous pregnancies, degree of pregnancy planning, perceived social support during pregnancy, acute illness relapses or psychiatric admissions during pregnancy, and the postpartum period.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics of the overall sample included frequencies (and percentages) for categorical and mean (and standard deviation) for continuous variables. Univariate differences in sociodemographic and clinical features, obstetric variables and social support related to parity were tested using t and χ2 tests for continuous or categorical variables, and non-parametric tests when necessary. In a first step, we divided the sample into two diagnostic groups: schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders.

In a further step, groups were analyzed according to motherhood (yes/no), and in a subsequent step, age at onset of psychosis (<20, 21–30, 31–35, >36) was considered the grouping variable.

All data were analyzed by using SPSS for Windows (Version 24).

ResultsCharacteristics of the female overall sample and stratified data by psychiatric diagnosisThe sample included 192 female patients, all of them fulfilling DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (see Table 1).

Demographic variables by diagnosis.

| Total sample | Schizophrenia | Schizoaffective disorder | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=192) | (n=147) | (n=45) | ||

| Age yr, mean (SD) | 48 (14) | 50 (15) | 42 (11) | <0.001 |

| Educational level, n (%) | 0.028 | |||

| Illiterate | 29 (15.1) | 27 (18.4) | 2 (4.5) | |

| Primary school | 66 (34.4) | 51 (34.7) | 15 (33.3) | |

| Secondary school | 64 (33.3) | 42 (28.5) | 22 (48.9) | |

| University | 33 (17.2) | 27 (18.4) | 6 (13.3) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.008 | |||

| Single | 75 (39.1) | 64 (43.5) | 11 (24.5) | |

| Married/partner | 67 (34.8) | 44 (29.9) | 23 (51.0) | |

| Separated/divorced | 38 (19.8) | 27 (18.4) | 11 (24.5) | |

| Widow | 12 (6.3) | 12 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Employed | 42 (21.9) | 31 (21.1) | 11 (24.4) | |

| Unemployed | 21 (10.9) | 9 (6.1) | 12 (26.7) | |

| Benefits | 103 (53.7) | 83 (56.5) | 20 (44.4) | |

| Never employed | 26 (13.5) | 24 (16.3) | 2 (4.5) | |

| Motherhood, n (%) | 0.061 | |||

| Yes | 96 (50) | 68 (46.3) | 28 (62.2) | |

| No | 96 (50) | 79 (53.7) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Age of onset of the illness, n (%) | 0.680 | |||

| <20 yr | 38 (19.8) | 31 (21.1) | 7 (15.6) | |

| 21–30 yr | 68 (35.4) | 51 (34.7) | 17 (37.8) | |

| 31–35 yr | 26 (13.5) | 18 (12.2) | 8 (17.8) | |

| >36 yr | 60 (31.3) | 47 (32.0) | 13 (28.9) | |

Bold text indicates a statistically significant correlation with a p-value less than 0.05.

A total of 66 women (34.4%) had finished primary school, being the most prevalent educational level in our sample. Most women were single (n=75, 39.1%) at the moment of the evaluation and were cohabiting with first degree family members (n=47, 24.6%). Women with an earlier age at onset were more likely to be single (p=0.006) than women with a later onset of disease. Regarding economic status, most patients were receiving benefits from the government due to their mental health illness (n=103, 53.7%). When stratifying by illness onset, the most common was found in the age range group from 21 to 30 years (<20yo: n=38, 19.8%, 21–30yo: n=68, 35.4%; 31–35yo: n=26, 13.5%; >36yo: n=60, 31.3%).

One-hundred and forty-seven (76.6%) women were diagnosed with schizophrenia, and 45 (23.4%) with schizoaffective disorder. When comparing the sample according to psychiatric diagnosis, women with schizophrenia presented a lower educational level (p=0.028) and were more likely to be single (p=0.008) and being on social benefits (p=0.001). Thus, although not statistically significant, women with a schizoaffective disorder showed a tendency towards higher rates of motherhood as compared to women with schizophrenia (p=0.061).

Motherhood versus non-motherhood on psychotic womenMotherhood was observed on the half of the female sample (n=96, 50%). Psychotic mothers were more likely to be married/having a partner (p<0.001) and had a later onset of disease (p<0.001) (Fig. 1) compared to non-mothers. The 70.7% (n=65) were mothers before the onset of the illness (n=65) and the 81.1% presented an obstetric complication (n=78). Sixty-one (63.5%) mothers reported a wanted pregnancy, but only 24 (25%) described some pregnancy planning.

Within the mothers’ group, only 2 (2.2%) required an intensification of their psychiatric follow-up due to clinical relapse during the pregnancy period, and 9 (9.9%) during the immediate postpartum period. Sixty-one (66.3%) of the mothers received an adequate social/familiar support during pregnancy and 45 (47.9%) were taking care of their children with their husband/partner at the time of the assessment.

When comparing by psychiatric diagnosis, only mothers with schizophrenia presented higher rates of abortion when compared with schizoaffective mothers (p=0.01) (see Table 2).

Motherhood and obstetric variables by diagnosis.

| Total sample | Schizophrenia | Schizoaffective disorder | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=96) | (n=68) | (n=28) | ||

| Maternity previous the onset of the illness, n (%) | 0.409 | |||

| Yes | 65 (70.7) | 47 (69.1) | 18 (64.3) | |

| No | 31 (29.3) | 21 (32.2) | 10 (35.7) | |

| Planned pregnancy, n (%) | 0.850 | |||

| Unwanted | 11 (11.5) | 7 (10.3) | 4 (14.3) | |

| Wanted | 61 (63.5) | 44 (64.7) | 17 (60.7) | |

| Wanted and planned | 24 (25.0) | 17 (25.0) | 7 (25.0) | |

| Obstetric complications, n (%) | 0.341 | |||

| Yes | 78 (81.1) | 54 (79.4) | 24 (85.7) | |

| No | 18 (18.9) | 14 (20.6) | 4 (14.3) | |

| Abortion, mean (SD) | 5.32 (5) | 6.86 (6) | 0.27 (0.65) | 0.010 |

| Clinical relapse on the pregnancy, n (%) | 0.179 | |||

| Yes | 11 (11.5) | 6 (8.8) | 5 (17.9) | |

| No | 82 (88.5) | 62 (91.2) | 23 (82.1) | |

| Mental illness on progeny, n (%) | 0.198 | |||

| Yes | 17 (17.7) | 14 (18.2) | 3 (10.7) | |

| No | 79 (82.3) | 54 (81.8) | 25 (89.3) | |

Bold text indicates a statistically significant correlation with a p-value less than 0.05.

Two main findings rise from the current study. Firstly, in our female psychotic sample we found that half of the women were mothers, being more frequent on the schizoaffective subsample than in the schizophrenia female group. Secondly, 81.1% of them presented an obstetric complication.

In our patients, maternity prevalence was estimated to be half of the sample (50%) as it was described in the previous studies. In fact, present rates of maternity amongst women with psychosis have increased in the past decades, reaching similar rates than the general population.4–13 Despite socio-cultural differences through countries, deinstitutionalization of women with severe mental disorders seems to have contributed to this increase in motherhood in women with psychosis.11

When evaluating characteristics of our sample we found that the most prevalent psychosocial profile seen in our patients was having finished primary school (34.6%), being single (39.1%) and receiving benefits (54.2%). Previous studies have reported that patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder consistently show lower educational levels, lower marital rates and reduced socio-economic status.5,15,29,30 Thus, it has been considered that the difficulties of getting married for a woman with schizophrenia are related to the disease's intrinsic factors, such as premorbid personality traits and inappropriate affection, as well as in the number of hospitalizations and cultural restrictions.4,6,15,31 The marriage rate of the patients in our sample might also be influenced by the patients’ age of illness onset, as it has been previously reported.6

In addition, in our sample, those women with earlier onset of illness were more likely to be single in comparison with those with later onset. Early onset of the psychotic illness have been associated with a poorer prognosis and outcome than the late onset disorder, causing a huge loss in the quality of life of patients and their families, in their physical health, and a high cost to society.28 Furthermore, our data suggest that those achieving motherhood present a later illness onset and reach maternity before the onset of the illness interferes in their daily-living functioning.18 Motherhood is a life-change experience with is frequently associated with multiple adversities and different concerns associated with infant well-being.28 A later age at onset may imply higher length or time of social and personal functioning, and subsequently, a higher probability to be mother for women with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders.28

Besides it was not a goal of the present study, is worthy to mention that almost 80% of the sample presented an obstetric complication with only a quarter of the sample presenting a planned pregnancy. With these results it has to be mentioned the need to promote reproductive health care for women with mental disorders and to seriously consider their reproductive life plan.32 Adequate pregnancy planning can help to avoid the abrupt and inappropriate discontinuation of treatment, the relapse of disorder, and poor obstetric and neonatal outcomes. If pregnancy is not desired, women should be advised about the most appropriate method of contraception, and also about treatment interactions that may increase contraceptive failure. If pregnancy is desired, we recommend a specific preconception psychiatric assessment in order to reach an individualized risk/benefit decision. The subsequent care plan should be designed by an expert perinatal psychiatrist, together with obstetric and neonatology specialists, so as to minimize the risks for both the mother and the new-born. Consideration of the reproductive life plan among women being treated for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders can help to promote perinatal mental health and to prevent unplanned pregnancies as well as improving clinical mental health outcomes for the mother with a decrease of undesired obstetric complications.

Care plans for women with schizophrenia may also include interventions targeting the mother–infant interaction. Women with schizophrenia may be at a higher risk of difficulties in mother–infant interactions.33 A recent systematic review concluded that the assessment of social risk factors in patients with acute onset or chronic psychosis during postpartum period should be examined in order to control their effects on the mother–infant relationship. Psychosocial environment can not only be a predictor of maternity in women with schizophrenia but also have an effect on children of mothers diagnosed with schizophrenia.34

Strengths and limitationsSeveral study limitations should be mentioned: (1) the small sample size could have limited the statistical power and impeded from performing more complex statistical multivariate analysis, (2) the lack of assessment of psychopathological symptoms with standardized and well-validated assessment scales, and (3) marriage and human reproduction are largely influenced by biological and cultural factors, not covered in this investigation, as this was not our main goal.

Despite these limitations, our findings have clinical implications for women with severe mental disorders and in reproductive ages while increasing the bulk of knowledge on primarily female study samples.

ConclusionsThis observational study of outpatient female patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder identified that maternity rate is high in this population. Psychotic mothers present unique needs that might be addressed. In this line, the current findings may help clinicians tailor individual care plane approaches that best meet individual patients’ pregnancy and maternity needs. Accordingly, clinicians might be aware not only on how to manage psychoses clinically, but also focus on their parenting skills, so as to minimize the negative impact on their children.35

Future research should be focused on the impact of psychosocial risk factors and clinical predictors of maternity. Personalized medicine includes the individual approach to patients in the context of the particular needs and conditions. Women with schizophrenia present particular health needs, which is more relevant at the reproductive stage of life. Identifying predictors may help the clinicians to better identify targets for preventive interventions.

FundingThe authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

The authors acknowledge the patients included in the study.