Targeted endoscopic biopsy for pathological characterization of malignant gastrointestinal lesions is crucial in gastrointestinal oncology. While most of the time this is easily achieved in modern endoscopy, difficult-to-access localizations may pose challenges to this end, e.g. proximal gastric, postpyloric and/or behind-the-fold colorectal lesions. Variable techniques, such as patient repositioning and/or manual compression, may occasionally be helpful to alleviate such constraints. By contrast, utilization of an Inoue-type cap has not been reported in this setting, which has been proven highly instrumental in my personal practice as is illustrated herein.

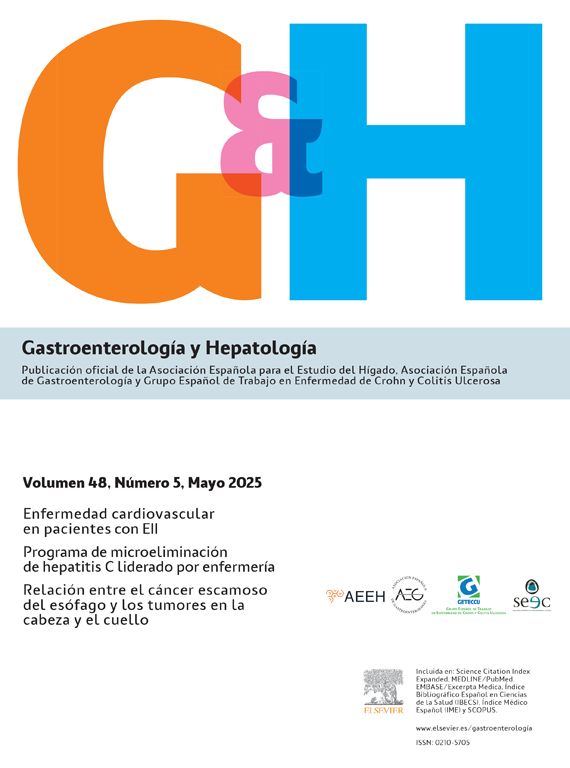

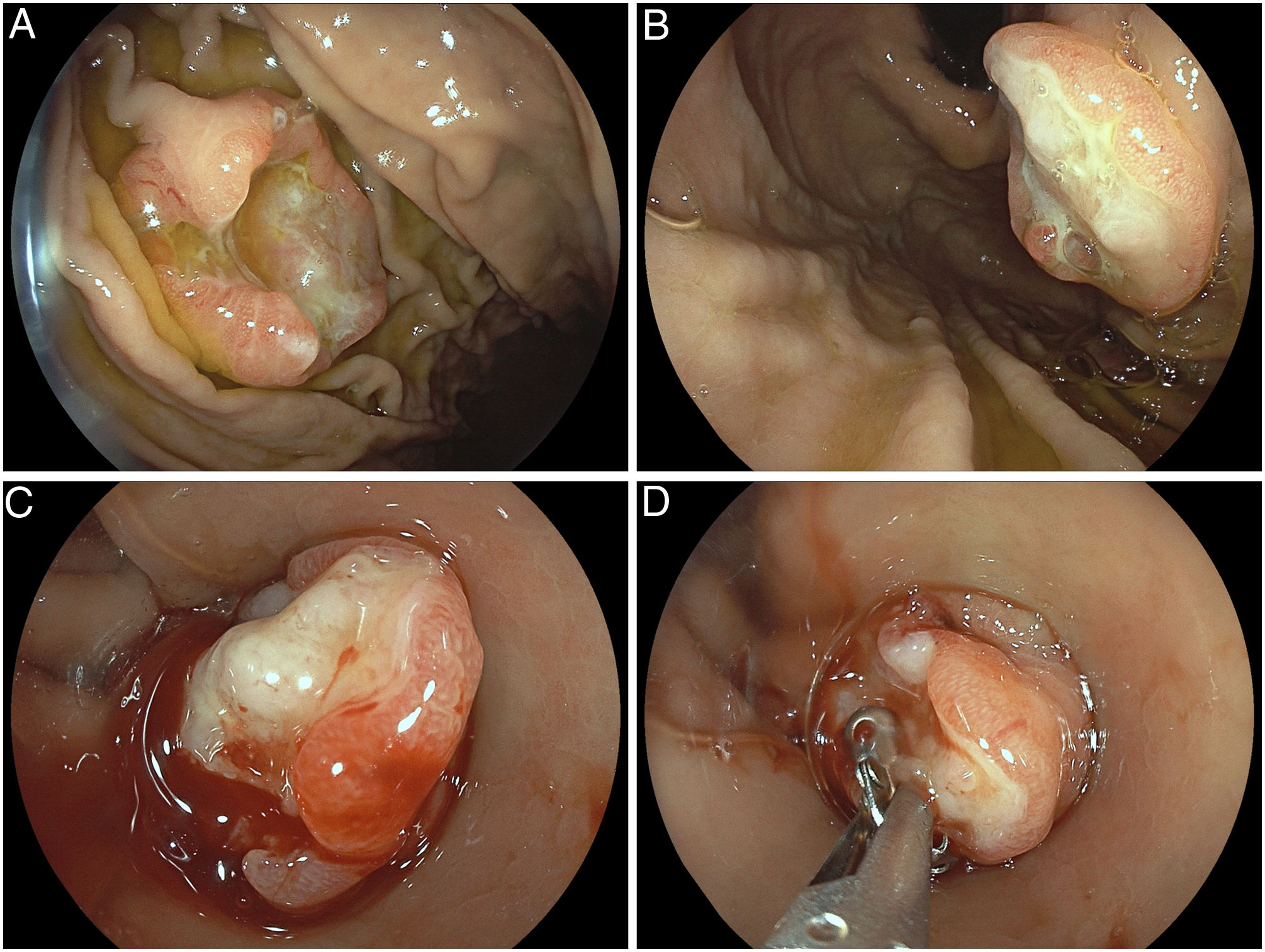

A 74-year-old male patient with metastatic melanoma with diffuse pulmonary lesions presented for esophhago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) for intermittent tarry stools. Two ulcerative lesions with raised edges emerged in the proximal stomach highly suggestive of (amelanotic) gastric metastases. Contrary to the greater curvature lesion easily accessible by standard biopsy (Fig. 1A), the second lesion at the lesser curvature in the high body, however, defied adequate biopsy targeting in both prograde and retrograde approaches due to too tangential an axis and lesional floppiness (Fig. 1B). After switching to cap-fitted endoscopy, the lesion was judiciously sucked into the cap, thus stabilizing it for intra-cap biopsies (Fig. 1C, D). Pathology indicated a dense infiltration by highly atypical cells with anisomorphic and basophilic nuclei (Fig. 2A, B – H&E ×2.5 and ×10, respectively) with positive immunohistochemistries for melan A (Fig. 2C) and SOX-10 (Fig. 2D) confirmative of melanoma metastatic to the stomach.1,2 Cap-fitted endoscopy is not routinely warranted in diagnostic gastrointestinal endoscopy. However, in difficult-to-access areas, e.g. behind folds and/or angulations with unstable scope positioning, utilization of a transparent cap oftentimes is indispensable to adequately evaluate a lesion.3 Likewise, targeted biopsy otherwise occasionally difficult in retroflexed positions might be streamlined by a cap attachment. The presented “intra-cap” approach might even increase diagnostic yield, given that full haptic control of scope position and full visual control of biopsy becomes feasible.

(A, B) Endoscopic visualization of two elevated nodular lesions with ulceration in the proximal stomach highly suggestive of gastric metastases, in part, easily accessible by standard biopsy (lesion in A) and another difficult-to-biopsy lesion (B) due to an overly tangential approach. (C, D) Cap-fitted endoscopy using a long-hooded cap with lesion stabilization after judicious suctioning with subsequent targeted “intra-cap biopsy” as a novel approach for difficult-to-access gastrointestinal lesions.

(A, B) Dense infiltration by malignant cells with anisomorphic and basophilic nuclei (H&E, ×2.5 and ×10, respectively). Dedicated immunohistochemistries revealing marked melan A (C) and SOX-10 (D) expression confirmative of gastric melanoma metastases (each ×10 – not shown immunohistochemistry for CK-18 negative).

Nothing to declare.