Rumours and misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine have been massively circulated on social media platforms, ranging from misleading information, hoaxes, and conspiracy theories to exaggerating stories mixed with the circulation of cultural myths regarding the vaccine.

MethodsThis study examines the contents of social media platforms such as Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, and WhatsApp posts, also sourced from other Indonesian online portal news and mainstream media websites.

ResultsThis research identifies quantitatively several rumours, misleading information, conspiracy theories, and other misinformation, resistance, and rejection toward issues related to the COVID-19 vaccine from March to April 2021. We then combine it with an analysis of the narratives of vaccine resistance and cultural myths that have made people hesitate or apathetic in participating in national vaccine programs by the Indonesian government.

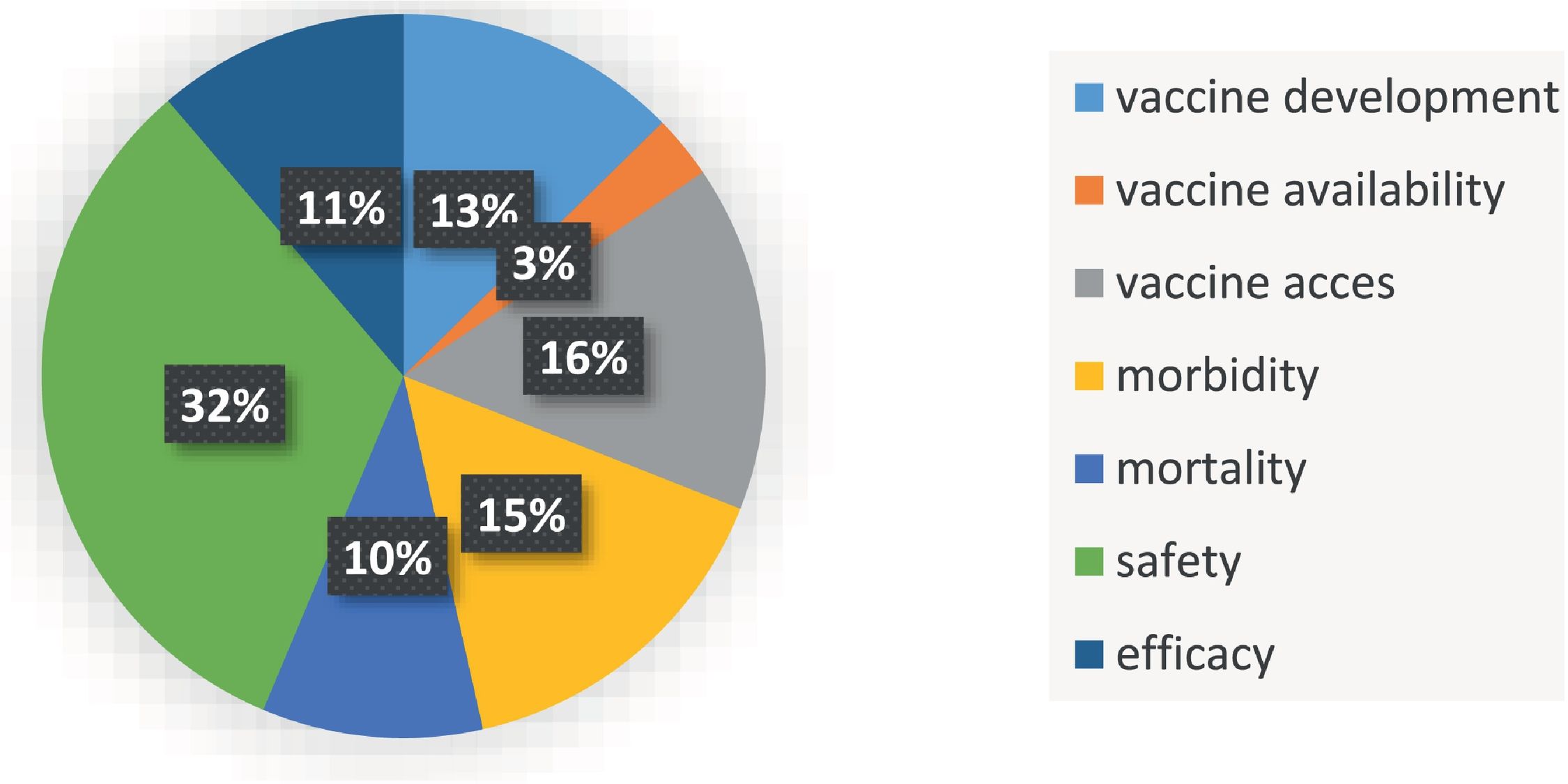

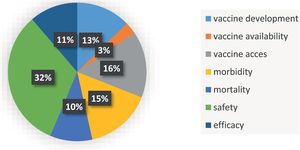

ConclusionSourced from the content analysis of this study, we categorised some themes such as vaccine development, availability, access, morbidity, mortality, harmful excesses, safety, and efficacy, both contained and presented in short narratives, visual graphics, memes, and cartoons. This study suggests that these rumours, misleading stories, and myths, may result in the Indonesian public's vaccine resistance and hesitancy, especially since May the Indonesian government stopped distributing the Astra Zeneca vaccines and the controversial issue regarding the availability of ‘Vaccine Nusantara’ (term as ‘Archipelago Vaccine’). This situation may influence the public's attitude to distrust the government and be distracted by misinformation about the vaccination program. Moreover, we see that cultural beliefs and religious stances have made complicated the hesitancy and resistance of the public against the COVID-19 vaccine.

En las plataformas de redes sociales se han difundido masivamente rumores y desinformación sobre la vacuna contra el COVID-19, que van desde información engañosa, engaños, teorías de conspiración e historias exageradas mezcladas con la circulación de mitos culturales sobre la vacuna.

MétodosEste estudio examina los contenidos de las plataformas de redes sociales como Twitter, YouTube, Tik Tok y publicaciones de WhatsApp, también obtenidos de otros portales de noticias en línea de Indonesia y sitios web de los principales medios de comunicación.

ResultadosEsta investigación identifica cuantitativamente varios rumores, información engañosa, teorías de conspiración y otra información errónea, resistencia y rechazo hacia cuestiones relacionadas con la vacuna COVID-19 de marzo a abril de 2021. Luego lo combinamos con el análisis de las narrativas de resistencia a las vacunas y Mitos culturales que han hecho que la gente dude o se vuelva apática a la hora de participar en los programas nacionales de vacunas del gobierno de Indonesia.

ConclusiónA partir del análisis de contenido de este estudio, categorizamos algunos temas como el desarrollo, la disponibilidad, el acceso, la morbilidad, la mortalidad, los excesos dañinos, la seguridad y la eficacia de las vacunas, ambos contenidos y presentados en narrativas breves, gráficos visuales, memes y dibujos animados. Este estudio sugiere que estos rumores, historias engañosas y mitos pueden provocar la resistencia y la vacilación del público indonesio ante las vacunas, especialmente desde que en mayo el gobierno indonesio dejó de distribuir las vacunas de Astra Zeneca y la controvertida cuestión relativa a la disponibilidad de la 'Vacuna Nusantara' (término como 'Vacuna del Archipiélago'). Esta situación puede influir en la actitud del público de desconfiar del gobierno y distraerlo con información errónea contra el programa de vacunación. Además, vemos que las creencias culturales y las posturas religiosas han complicado las vacilaciones y la resistencia del público contra la vacuna COVID-19.

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic spreading to 219 countries, including Indonesia.1 More than 36 000 people died and 1.3 million people were infected during this year. This number is the highest number of cases and deaths in Southeast Asia, far exceeding the number of deaths in the United States.2,3

Various efforts have been made by the government and the community to deal with this epidemic, covering health protocols, regional restrictions, and providing free vaccinations to entire communities. President Joko Widodo became the first person to receive the vaccine on Wednesday, 13 January 2021, followed by priority vaccine recipients, such as health workers, assistant health workers, support personnel working in the health service facilities, Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI), Indonesian National Police, law enforcement officers, and other public service officers including popular celebrities.

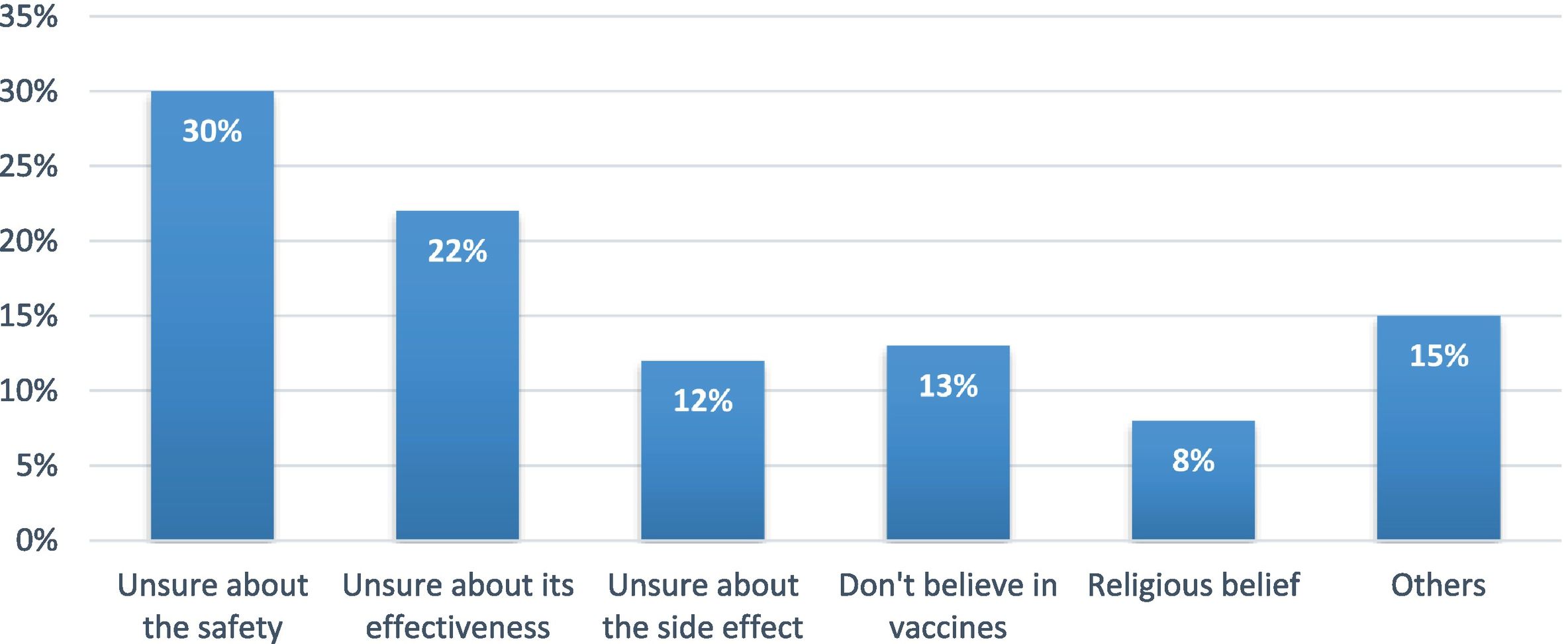

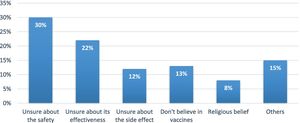

However, public acceptance of COVID-19 has not always been positive. According to the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance survey conducted by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia in collaboration with WHO and UNICEF in November 20204, approximately 74% of respondents were aware of the potential COVID-19 vaccine being developed although the information obtained varied by region and the economic status of respondents. Of the number who acknowledged about the vaccine, about two-thirds of the respondents are willing to be vaccinated, while the rest are still doubtful and questioning factors related to the vaccine (see Fig. 1). According to the survey conducted by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia, the most common reason behind COVID-19 vaccine refusal related to vaccine safety (30%); doubts about the effectiveness of the vaccine (22%); distrust of vaccines (13%); concern about side effects such as fever and pain (12%); and religious reasons or the halal-ness of vaccines (8%)5 (See Fig. 2).

General reasons behind COVID-19 vaccine refusal.21

The community resistance comes out in the form of rumours circulated among citizens and other private spheres. Furthermore, mistrust and doubts about COVID-19 vaccines were also shared in various visual contents uploaded on digital media platforms. As a result, the information spread massively creating bigger doubts or apathy among the citizens in joining the national vaccination program. This study, therefore, aims to investigate kinds of issues about anti-vaccines circulated through social media and online portals. The reason for doing this study is to analyse the rumours that could cause or influence the hesitancy and resistant attitude of those who remain reluctant to receive vaccines into their body. Moreover, we also try to analyse the narratives of vaccine resistance and rumours circulated to provide views to the policymakers to design a communication campaign to persuade people to come to the vaccination centres, since, according to the previous research from the Indonesian Ministry of Health (2020)6, the middle to lower class people are among those who hesitate to participate in vaccination program due to their little understanding and low information exposure toward the COVID-19 and the vaccines.

This research found, so far, no single issue in any academic journal and other publications on the persistence of rumours, sentiment, or negative campaign against the national Covid-19 vaccination program introduced by the Indonesian government. This research is particular and initial in the context of media and health studies, the approach that remains less attempted by scholars in Media and Communication studies. Indeed, the relations between Media Studies and Health Studies is actually relevant and important. Many health issues and campaigns dedicated to publics seem to be ignored and sometime understudied. We believe that messages, through pictures and verbal languages, are crucial and important for health campaigns and communications to the people for enhancing people’s knowledge and understanding about health problems. Unfortunately, there are still messages that do not arrive or transmitted properly to the large communities. In addition, in the era of digital, social media have become very popular medium for people to connect with others and to search for information and new knowledge from social media. Social media also have become a new outlet to express people’s freedom to speak, show opinions, rejection, and other political activism to oppose or express their attitude or response toward health policies or programs designed and promoted by the government to them, including this national vaccination program, which was seen carried more government politics than the well-being purposes of the vaccine.

MethodsThis research applied combination methods between a quantitative and a qualitative. In the first step, this research identifies quantitatively several rumours, misleading information, conspiracy theories, and other misinformation, resistance, and rejection toward issues related to the COVID-19 vaccine sourced from social media and online news portals, from March to April 2021. We combined the quantitative data gained from social media platforms with an analysis of the narratives of vaccine resistance and cultural myths that have made people hesitate or apathetic in participating in national vaccine programs by the Indonesian government.

To gain quantitative data, which are numbers of rumours and so forth, we use a content analysis for this study. This research categorised some themes such as ‘vaccine development,’ ‘vaccine availability,’ ‘vaccine access,’ ‘morbidity,’ ‘mortality,’ ‘negative excesses,’ ‘safety,’ and ‘efficacy,’ that contained and presented in short narratives, visual graphics, memes, and cartoons available in social media platforms. Yet, the presentation and analysis of this research paper are focused more on the visual materials and qualitative narratives. The method of analysis used in this study is derived from the tradition of media studies, which gives more attention to the importance of the connotation meanings of the visuals rather than a description of the quantitative data. In addition, this research attempts to provide a new model of research in health studies by combining the perspectives of media studies and (Public) health studies, which is less attempted by both scholar in media studies and in health studies.

Results and discussionDuring the introduction of the Indonesian government to launch the starting of vaccination program to reduce the pandemic prevalence and to protect the society with the antibody and immune against the virus, pros and cons responds were circulated among the people through social media, particularly. Some people agreed and positively respond to the program, but some others rejected the program due to lack of understanding and knowledge toward the vaccine information. Therefore, this research investigated the people’s reactions to the information related to the national vaccination program launched in 2021–2022. This research began with the quantitative identification of rumours and misleading information about COVID-19 vaccine resistance circulating in various digital platforms. The research saw how the distribution of hoax information circulated through the website like cekfakta.com1 using the keyword ‘vaksin covid'.7 The result revealed that there are 487 contents on digital platforms that contain false information related to COVID-19.

After collecting data using a Google search engine, this current study gained data about false information related to vaccines (see Fig. 1). Using the 7 keywords, this study found that the issue of safety has become a major concern in vaccines. Rumours and false information about the effect of vaccines (32%) have been circulated largely among the netizens and social media account holders. The second concern of the people is on the vaccine access. People were wondering where and how to get access (16%) to get a job from the government. They also were wondering whether the vaccine was free or payable. Yet, people did not care about the availability of the vaccine (3%), whether the vaccine was in stock or out of stock. These results show us that false news and hoaxes have been circulated and distributed among social media users since the absence of comprehensive information. The government is less transparent in distributing information and providing sufficient communication and information to the people.

Apart from the quantitative content analysis, we also conducted a qualitative text analysis of particular visual images circulated on social media, which have received much attention and are being circulated through social media such as, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and personal Whatsapp during the vaccination program in the late 2021–2022. The following analyses have been attempted to examine some examples of cartoon images circulated on social media.

Some hoax information about the COVID-19 vaccine could be found in tweets and Facebook posts during March and April 2021. For instance, a Twitter account with username @The__Mocasin_ stated that the COVID-19 Pfizer vaccine might lead women to infertility (02 March 2021). Moreover, Facebook accounts with the username indra.utama.522 uploaded a letter with “Dinas Kesehatan Pemerintah Kota Pekanbaru” (Health Department of Pekanbaru City Government) as the letterhead, containing an instruction to return the COVID-19 vaccine due to an evaluation of the COVID-19 vaccine distribution by the government of Pekanbaru Riau (17 March 2021). Facebook account with the username Dian Ekawati II uploaded a narrative that stated that the COVID-19 vaccine has mutated and turned into thousands of COVID-19 cases worldwide (18 January 2021). Twitter account with username @Humic9 claimed that the Minister of State-Owned Enterprises, Erick Thohir, revealed the existence of a chip inside the COVID-19 vaccine (11 April 2021), and some others. There is much more hoax information that has been successfully verified through the website cekfakta.com. Even so, the authors can still find hoaxes and misleading information spread through personal WhatsApp groups or other social media posts.

Departing from this issue, the research thus interested to analyse the narratives related to vaccine resistance and cultural myths in the various digital platforms that have been circulated through the social media posts. This research selected some visual/images and verbal posts in order to examine messages in the form of visual content, emphasising that humans’ brains process a picture 60 000 times faster than text.8 With this Eisenberg’s suggestion, this research assumed that digital platform users receive visual content faster than other types of content, whether it contains negative or positive information. The researchers continued to collect visual content from numerous sources, namely Facebook, Twitter, online news portal, and WhatsApp Groups distributed for social media users in Indonesia. Among the collected visual contents, the authors selected 8 visual contents representing rumours and misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine during the year 2022. Furthermore, this research browsed the source of those visual contents to find their originality; then analysed the 8 examples of visual content to see the existing written and implied messages, including knowing how netizen responds to rumours about vaccination in Indonesia.

Vaccine and politics: When people’s representatives refuse vaccinesThe visual portrays a woman wearing a red shirt with a white muzzle bull logo, the logo of Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan (Democratic Party or PDIP). There is a word balloon that reads "I Refuse Vaccines" from the woman. The woman is Ribka Tjiptaning, a Member of the Indonesian House of Representatives Commission IX from the PDIP party. The figure illustrates the situation of Ribka who stated that she refused to be vaccinated at the DPR Commission IX Working Meeting with the Ministry of Health, BPOM, and Biopharma. Ribka also stated that she would rather pay a fine instead of being injected with the vaccine on 12 January 2021. Ribka’s statement has become a trending topic on various social media platforms as seen in Fig. 3. Ribka’s statement was based on her distrust of the safety of currently circulating vaccines, hence she would rather pay a fine if the government forced her and her family to get vaccinated. “I still do not want to do it regarding the vaccine, although 63-year-old people are eligible to do it (I am 63 years old already). If living in Jakarta obliges my entire family and me to pay a fine of Rp. 5 million, I would rather pay”

House of Representatives Commission IX Member Ribka Tjiptaning Reject COVID-19 Vaccine.22

Ribka’s action was a form of protest against the business game in imported vaccines. She stated bluntly that the issue of COVID-19 vaccines for Indonesian citizens should not become a business which benefits certain people. If the vaccination program is seen through the lens of business, the vaccine’s safety might be ruled out in the name of business benefits and thus, people’s safety might also be put in danger.9 Many responses from the public have circulated on social media, both the pros and the contras. However, some netizens do not agree with Ribka’s statement and find her actions arrogant and provocative. Ribka’s action was also linked to political issues, which people consider her as ‘someone who forgets her origins’ for betraying the government (and her party, PDIP) by standing against the national vaccine program. The rumours grew bigger as Ribka Tjiptaning was suddenly rotated from Commission IX to Commission VII. Comments on social media were increasingly becoming political, as stated by Muhammad Arsyad Habe through his Twitter account @arsyad_habe below: They should’ve been grateful because one of them vocally refused the COVID-19 vaccine. Why did they rotate her instead? Moreover, she admitted herself as ‘pekai’ [sic.](‘pekai’ means PKI, Indonesian Communist Party)..,

So, the issue has been exaggerated to the issue of politics, more specifically to the sensitive issue in Indonesia that is communist, to reference Ribka and those who reject vaccines as if they are part of the former Indonesian Communist Party.

Anti-China: Vaccine is okay, as long as it is not from ChinaPractically, most people in Indonesia are accustomed to the presence of vaccines as a solution to a public health crisis (see Fig. 4). Vaccines are expected to be a preventive or a mitigation effort in preventing, breaking, or at least slowing down the process of transmission of disease. The problem is that some COVID-19 vaccine candidates were made faster compared to the vaccines for previous diseases, and those vaccines went through many years of clinical trials before being distributed to the public. Especially when the government announced, it had purchased the vaccine for China. There is a visual image that shows how enthusiastic vaccine recipients are about receiving the vaccine. However, they suddenly disappear when the doctor informs them that the vaccine to be injected is from China.

The caccine has come.23

The issue continued to flourish after the government announced the arrival of 3 million doses of the Sinovac vaccine in December 2020 of the total budget for vaccination of Rp. 17 trillion by 2021.10 Almost simultaneously, the Chinese government stated that the efficacy of their COVID-19 vaccines is low, including the Sinovac vaccines used by Indonesia.11 Based on the Phase III clinical trial in Brazil, the efficacy of the Sinovac vaccine is only 50%. Meanwhile, the result of an interim analysis of clinical trials in Bandung showed the efficacy of Sinovac at 65%. Even though the Ministry of Health has confirmed that ideas or innovations are effective, and have better immunogenicity and efficacy than the current conditions, people already doubt the effectiveness and safety of Chinese vaccines. This issue can be seen in another cartoon image, which also illustrates the public’s doubt about the Sinovac vaccine.

The issue regarding Sinovac or Sinopharm vaccines is not only about the efficacy of the vaccine, but it is also about the source of the vaccine. The anti-China sentiments in Indonesia remain as pressure on Joko Widodo’s government due to the close relationship between Indonesia and the Chinese government for some infrastructure projects, the mining industry, and other physical developments in Indonesia in the last 5 years. So, the anti-China sentiment continues to become a threat to the national vaccination program. Nevertheless, the Indonesian government seems to ignore the sentiment and continues to import the Sinovac vaccine from China up to the recent (July 2021) batch.

By parodying the well-known eucalyptus oil product advertising tagline, “Buat Anak Kok Coba-Coba” (why children are for trial), the illustration of the cartoon image tries to show that Sinovac is the weakest type of COVID-19 vaccine. Through this illustration, the creator warns the government not to be rash in choosing and purchasing the COVID-19 vaccine type for the citizens. The sentence “Buat Rakyat Kok Coba-Coba” (why people are on trial) contains a profound message so that the government guarantee the safety of vaccines that will be distributed to the public. Hence, the vaccine given will not endanger the public’s health.

Vaccination between business and pessimistic spaceThe visual content is a parody of vaccines played by Asterix cartoon characters (see Fig. 5). As shown in the illustration, there are 3 figures, namely Asterix (figure with black shirt and red pants), Obelix (figure with white-blue striped pants), and Panoramix (figure in white clothes, red cape and a long white beard). In this illustration, Panoramix explains that the concoction he is making is not ready yet, so the anti-virus has not worked. Obelix then answered him by saying, “Ga usah mateng-mateng, yang penting ada aja dulu” (It does not have to be overcooked, what matters is its presence). Meanwhile, Asterix can only wait with a surrender face. The visual was published in online Tempo magazine on 24 October 2020.12 At the time, Indonesia’s vaccination program had not yet started, and the citizens were busy with discussions about the arrival of vaccines from abroad. In Indonesia, the vaccination program started in January 2021 with President Jokowi as the first vaccine recipient. The conversation in the picture above satirized the COVID-19 vaccine presence plan in Indonesia, which was deemed not yet fit for wide distribution. A longer clinical trial is needed to know the efficacy of vaccines. Moreover, the clinical trial aims to ensure that the vaccine does not cause or only cause a minimum side-effect, both in the short- and long term.

The weak prophylactic.24

The presence of various COVID-19 vaccine brands within less than a year after the virus was found has triggered suspicions among the public. One reason behind the public mistrust relates to the notion of business interests among pharmaceutical companies worldwide in vaccine selling. The research of Calnan and Douglass shows that the low public trust in the pharmaceutical industry is one factor that creates vaccine hesitancy and anti-vax movement in society.13 The term vaccine hesitancy refers to the length of time a person accepts or refuses to be vaccinated. Meanwhile, the anti-vax movement is defined as an active campaign of groups who refuse to receive the vaccine itself. The lack of trust in the pharmaceutical industry stems from the longstanding negative reputation of the industry. To date, pharmaceutical companies are often accused of being involved in various cases, such as bribery of health workers and clandestineness in clinical trials of vaccines to neglect or cover up the side effects of vaccines.

Vaccine side effect transparencyNot only the COVID-19 vaccine, but a different post-vaccine body reaction can also occur after the injection of other vaccines. However, regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, numerous confusing information about the vaccine's side effects circulates in the digital platform, causing resistance issues in society. Illustration about vaccine hesitancy caused by the mixed information about vaccine side effects was also illustrated in another cartoon published in Republika News online.14 In a vaccination room filled with people queuing with their masks on, one of the vaccine recipients was seen passing out and was carried on a stretcher by 2 officers. When someone from the queue asks why that vaccine recipient passed out, one officer only gives a short answer by saying that the recipient skipped his breakfast. The image shows the lack of transparency regarding the vaccine side effect which should have been delivered not only from the international journals and be understood by a limited circle. Therefore, there must be transparency of information that reaches the public widely. In addition, the information should be easy to comprehend so that the public can understand the issue clearly, including those related to the side effects of each vaccine brand distributed by the government.

The Ministry of Health has elucidated some information concerning the COVID-19 vaccine side effects through official websites. The Ministry of Health then introduced the word KIPI,2 an abbreviation for Kejadian Ikutan Pasca Imunisasi (Adverse Event Following Immunisation). The government also provide reporting services to people who experience several side effects after vaccination. From the first period of Indonesia’s COVID-19 vaccination program until 16 May 2021, the National Commission of KIPI has received 229 reports of serious adverse events following immunisation, consisting of 211 cases from Sinovac and 18 cases from AstraZeneca vaccine. Furthermore, the report on mild adverse events following immunization consists of 10 627 reports, of which 9738 cases came from the Sinovac vaccine, and 899 cases came from the AstraZeneca vaccine.15 Adverse events following Immunisation may increase public doubt about vaccine safety. Therefore, it is crucial to report the post-vaccination symptoms to investigate further whether the vaccine causes the symptoms socialisation about KIPI also needs to be disseminated.

Microchips in the vaccineThe visual content from Kumparan.com16 comes out in a comic that tells the story of 3 men who talk about the COVID-19 vaccine. In the first scene, the first man seems to question the government’s policy, which obligates people to get vaccinated at personal expense. The second man responds to the first man by saying, “Ini penyakit kok dibisnisin???” (Why does this disease become a business?). Eventually, the 3 men decided not to get the vaccine because they had no money. Then in the second scene, there is a man dressed in a white shirt as a representation of President Jokowi. The man dressed in white then tries to explain that the COVID-19 vaccine has been made free for all Indonesians so that there is no longer any financial obstacle to getting the vaccine. However, the third scene shows the tense faces of the 3 men by imagining a scene from the movie Attack on Titan. The reason is that those 3 men assume that the COVID-19 vaccine can turn humans into Titan, as happened in the series.

Attack on Titan is an anime series that airs on Netflix, Viu, and other paid streaming channels. The series tells a story about the struggle of Eren Yeager and his friends in combating the Titans who attack their home. This series portrays a titan as a giant creature that physically looks like a human but with a disproportionate body shape, such as a tremendous head, small hands, or a spread-out mouth. The Titans only have one purpose in life, which is to prey on the human body.

Not long before the implementation of the national COVID-19 vaccine program, the word “Titan” became a trending topic on Twitter. As a result, many people decided to refuse to get vaccinated simply because they were afraid that the vaccine contained a hazardous serum that could turn humans into Titans. As shown in a tweet from an account with username @themekamu: “Suntik vaksin bareng-bareng, kalau berhasil kita sehat bareng, tapi kalau gak berhasil kita jadi titan bareng-bareng” (Let’s get vaccinated together, if it works, let’s be healthy together, but if it does not work, let’s become titan together) or a tweet from an account with username @b3b40rtu: “Gak mau divaksin, nanti jadi titan” (I don’t want to get vaccinated. I may turn into a titan [giant]). This trending topic is rooted in the appearance of a serum that can turn humans into Titans in one episode of the Attack on Titan series. The aforementioned serum can react on the people of Eldia who are deemed as Subjects of Ymir. The main composition of the serum comes from Titan’s spinal fluid that quickly evaporates upon contact with air. Therefore, the serum is stored in an air-tight container that looks similar to the vaccine storage, including COVID-19 vaccines. The Ministry of Communication and Information also responded to the fuss caused by this “titan” topic during a live broadcast on the socialisation of COVID-19 Vaccines (13 January 21) in the Ministry of Communication and Information’s official YouTube channel.

Before the topic of Titan widely spread, the COVID-19 virus had always been linked to various conspiracy theories. One of the most popular theories is the existence of a microchip in the COVID-19 vaccine, which subsequently is implanted in the human body. This rumour started to emerge on 18 March 2020, when Bill Gates answered questions about the pandemic happening in the United States. During the interview, Gates predicted that someday, every human would bring a digital passport as a personal health record, such as an e-vaccine card or a digital certificate that enables people to return to their activities in the new normal era. However, as time went by, Gates’s statement was misinterpreted as a biohacking to modify the body with technology. This rumour then developed into a notion that vaccine becomes a way to implant microchips in the human body.

The vaccine is rejected, the law will actIn February 2021, the government issued Presidential Regulation Number 14 of 2021 regarding the Procurement of Vaccines and Implementation of Vaccination in the context of dealing with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In the regulation, there is a warning about punishment for Indonesian citizens who refuse vaccination (see Fig. 6). It is stated that every person who has been designated as a vaccine recipient who refuses will receive administrative sanctions in the form of: (a) post-ponement or termination of the provision of a social guarantee or social assistance; (b) suspension or cessation of government administrative services; and (c) fines. This policy aims to ensure that people take part in the COVID-19 vaccination because the vaccine refusal will hinder the prevention of COVID-19 spread.

When the vaccine is rejected, the law will act (Vaksin Ditolak, Hukum Bertindak).25

This visual tries to compare the issue of romance and health. As shown on the left side of the frame, a broken-hearted man comes to see a shaman, asking for help with his unlucky romantic life. The phrase “Cinta Ditolak, Dukun Bertindak” (When love is rejected, the shaman will act) appears in this frame, delivering a message that the man will ask for the shaman's helps to force someone to accept his feeling. A shaman is a traditional practitioner who remains influenced and regarded by the Indonesian people, especially the village people or traditional remote communities, or even some people who still believe in the supernatural power of Shaman and black magic.

In comparison, we can see also in the cartoon that there is a man who refuses to get vaccinated by the health officer in a complete hazardous material (hazmat) suit on the right side of the frame. The health officer then says, “Denda 5 Juta!” (five million fines!). The illustration implies that if the man refuses to get vaccinated, he needs to pay Rp. 5 million fines. Moreover, the phrase “Vaksin Ditolak Hukum Bertindak” (When the Vaccine is rejected, the Law will Act) also appears in this scene, delivering a satirical message that the government’s vaccination program is performed with coercion and does not fully stand on the human rights.

Varying netizens' responses regarding the sanctions for residents who refuse the COVID-19 vaccine continue to rise on social media, particularly when the government decided to post-pone using the AstraZeneca vaccine in March 2021 as it was suspected of causing blood disorders. Various responses then emerged on the social media of mass media.

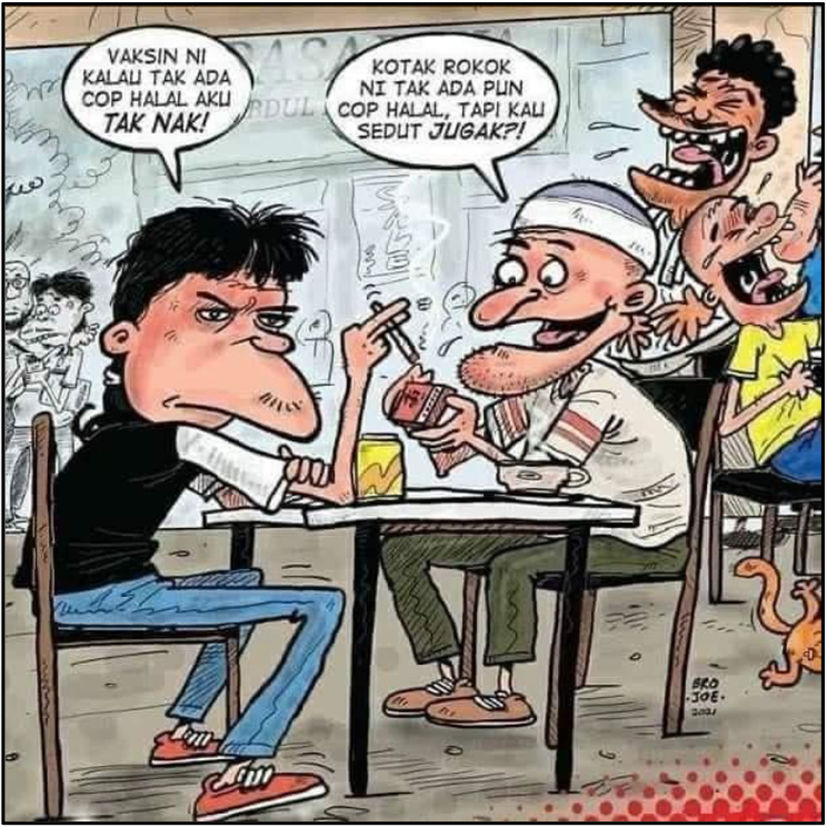

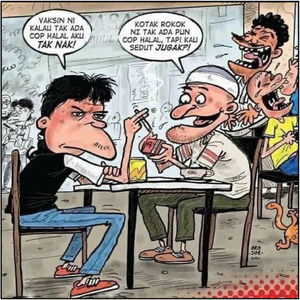

Halal and haram about vaccineThe last visual content we analysed came from Malaysia. The cartoon has been circulated on Facebook and is widely shared by users from Indonesia. In the cartoon illustration, 2 men seem to have a conversation in a coffee shop. The man in a black shirt and a cigarette in his hand says that he will not be willing to get vaccinated if the vaccine does not have a halal label. While holding a pack of cigarettes, the man in a white shirt replies to the man smoking in front of him by saying that his cigarettes also do not have a halal label and emphasises the fact that he is still willing to smoke them. The statement implies a satire towards people who do not want to get vaccinated because of the halal label.

Halal-related issues have become one of the main factors in Indonesian resistance to the COVID-19 vaccination program (see Fig. 7). The notion of banning the Chinese COVID-19 vaccine then circulated on social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook. The hate of some people toward the figure of Minister of Marine and Energy, Luhut Binsar Panjaitan (popularly called LBP) and cynicism toward his close connection to Chinese companies, which received a good welcome from the Jokowi’s government, has become part of the issue raised by the haters about vaccination program. Just like the example of the following tweets: The LBP [Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, a controversial figure of Minister of Marine and Energy] wants to vaccinate 100 million Indonesian people with the Chinese COVID. The MUI has banned this vaccine, so it is Haram for Muslims to participate in the vaccine. I REFUSE)

Halal vaccine.26

Another issue that struck the audience and circulated through social media is the issue of halal and related to particular regional places in Indonesia that are considered conservative provinces such as Aceh and West Sumatra. Aceh and West Sumatra are two provinces with the lowest willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination. The acceptance rate in Aceh only reaches 46%, while in West Sumatera, it is only 47%. These data are retrieved from a survey conducted by the Immunization Technical Advisory Group (ITAGI), the World Health Organization (WHO), and UNICEF, involving 115 000 people from all over Indonesia provinces. Some groups say they refuse vaccines due to side effects on health and the issue of halalness (bbc.com, 2021).17 Issues concerning the halalness of vaccines have occurred in Indonesia before. In 2017, people were reluctant to do measles and rubella (MR) immunization for toddlers because they doubted about its halalness.18 This condition shows that the association between religious and political issues will turn into something that triggers pros and cons among the Indonesian people. The people of Aceh refuse the COVID-19 vaccine because it contains many disadvantages, and according to the Acehnese ulama, it is haram. The central government has no right to interfere in the matter of the law of Haram based on faith because the matter of religion is the right of Aceh’s Government, not the central government of the Republic of Indonesia. If the central government insists on imposing its will, the people of Aceh are ready for war..!!

The development of issues related to the halalness of the COVID-19 vaccines has frequently been countered by the Government through various media channels. The Council of Indonesian Ulama (MUI) even stated that the Sinovac vaccine is halal and can be used by the public.19 Through numerous press releases and posts on digital platforms, the government urges the public to stop debating on the halal and haram of the Sinovac vaccine to avoid misinformation. Nevertheless, the issue continues to spread, targeting the next COVID-19 vaccine brand, AstraZeneca. The AstraZeneca vaccine was then declared haram by MUI through Fatwa Number 14 of 2021.20 This statement is based on the fact that AstraZeneca contains enzymes derived from swine. Although AstraZeneca is proven haram, MUI still allows the use of this vaccine because of the emergency and the urgent need to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic.

ConclusionThe COVID-19 vaccination is one of the efforts made by the Indonesian government to suppress the increasingly massive virus spread. However, the lack of accurate information and reliable sources has led to the emergence of a vaccine-resistant group. As a form of communication, the vaccine-resistant community voice their opinions through visual content. Various visual contents that have been previously analysed show that some factors affecting the resistance of Indonesian people to the COVID-19 vaccines include cultural factors, religious (halal-haram) factors, and apathetic behaviour towards the government.

Throughout this research, we gain quantitative data on the distribution of thematic issues circulated and distributed on social media and online portals. The major issues related to the COVID-19 vaccination program are the effects of the vaccine and the access to jobs from the government. From these quantitative data, it appear that rumours have been circulated due to the lack of information and explanation about COVID-19 and less openness or transparency of the government in distributing the information and clear messages about the vaccines and how the government’s design and scenarios regarding the vaccination program for the whole citizens. Too much information hidden will make society lack understanding and perceive negatively the vaccination program. As a result, hoax information, fake news, and rumours circulated among the people then become circulated and believed as the true information, which in turn becomes a threat to the vaccination program. This is obvious when social media followers tend to consume the rumours and “conspiracy” theories making them resist participating in vaccination programs. As such, the rumours and “conspiracy” theories against vaccines could be countered by the government by circulating and communicating accurate information about vaccination and its related issues. This study suggests that when the majority of society are informed and held little knowledge about vaccine, then other issues such as politics, anti-racism, and religious issues have disturbed and distracted the success of the vaccine program in Indonesia, and it may be in other countries in Southeast Asia, which it also needs to be scrutinised. As one of the images found in this study was circulated in social media followers in Indonesia came from Malaysian cartoon producers, so the anti-vaccine movement should also be resisted in other countries outside Indonesia.

In the context of media and health studies, this research suggests that the (public) health studies so far focus more on single message and top down (health’s perspective) in disseminating information to various levels of society. The use of medical verbs and languages, sometime, is not easy being understood by ordinary people and low-level education and information literacy of society. Therefore, the messages conveyed likely do not well-received or not as expected by the health professionals including the government. Health policy issued by the government in the event of pandemic, if did not convey accurately and using the people’s language or local culture, could potentially be rejected or opposed, or worst, causing public sentiments and negative responds. In the era of digitalisation and the popularity use of social media, rumours, gossips, and hoaxes information have been easily transmitted, distributed, and circulated. Thus, the role of media studies in interpreting the meanings and understanding the views of audiences and users of social media becomes relevant and substantial. Public health communication needs to be well designed and carefully distributed transparently and accurately, particularly in the era of networked society when social media become the communal tools to initiate people’s movements and reactions to the political authority.

FundingUniversitas Airlangga, Indonesia

This study is a part of COVID-19 research funding from LPPM Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. The author (s) would like to gratitude to participants and facilitators who suppored in this study.

Cekfata.com is a collaborative fact-checking project built on the Yudistira API by MAFINDO (Indonesian Anti-Defamation Society), in collaboration with several online media members who are members of AJI (Aliance of Independent Journalists) and AMSI (Indonesian Cyber Media Association) and supported by Google News Initiative and Intenews as well as FirstDraft.

WHO refers to the KIPI as Adverse Event Following Immunization (AEFI). AEFI describes any unwanted sign of events that occurs after immunization and does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the vaccine. Symptoms of AEFI can be in the form of mild symptoms, discomfort, or abnormalities in the results of laboratory examinations.