Chronic diseases and comorbidity are important predictors of depression and anxiety, the two most common disorders of poor mental health. Meanwhile, the pandemic increases anxiety and depression levels, alongside declined quality of life (QoL), the same way that comorbidities are associated with severity of COVID-19 progression. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of anxiety and depression, as well as the QoL among patients with chronic medical conditions in Amman, Jordan, in the post-pandemic period.

MethodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted among patients with comorbidities using a validated questionnaire consisting of 3 parts. Anxiety and depression prevalence were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), while the QoL in terms of physical, psychological, social, emotional, and general mental health was evaluated using the SF-36 QoL questionnaire.

ResultsA total of 150 participants (mean age=55±13 years) were enrolled in the study. Most participants reported a significantly elevated level of borderline abnormal or mild anxiety (44%, P<.0001). The QoL scores indicated relatively poor well-being, particularly in the physical role (29.2±45.5) and emotional role (26.2±4.0) domains (P<.05). Statistical significance was observed between HADS anxiety or depression scores and variables, such as age, education level, and comorbidities.

ConclusionThis study's findings provide insights into the adverse psychiatric consequences, high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms, and reduced quality of life among patients with comorbid conditions post-COVID-19 pandemic.

la comorbilidad de enfermedades crónicas es un predictor importante de depresión y ansiedad, los dos trastornos más comunes de mala salud mental. Mientras tanto, la pandemia aumenta los niveles de ansiedad y depresión, junto con la disminución de la calidad de vida (QoL), de la misma manera que las comorbilidades se asocian con la gravedad de la progresión de COVID-19. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar la prevalencia de la ansiedad y la depresión, así como la calidad de vida entre los pacientes con afecciones médicas crónicas en Amman, Jordania, en el período posterior a la pandemia.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal descriptivo entre pacientes con comorbilidades mediante un cuestionario validado que consta de tres partes. La prevalencia de ansiedad y depresión se evaluó mediante la Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (HADS), mientras que la CV en términos de salud física, psicológica, social, emocional y mental en general se evaluó mediante el cuestionario de CV SF-36.

ResultadosUn total de 150 participantes (edad media = 55±13 años) se inscribieron en el estudio. La mayoría de los participantes informaron un nivel significativamente elevado de ansiedad limítrofe anormal o leve (44%, P < 0,0001). Las puntuaciones de CdV indicaron un bienestar relativamente bajo, particularmente en los dominios del rol físico (29,2±45,5) y del rol emocional (26,2±4,0) (P < 0,05). Se observó significación estadística entre las puntuaciones de ansiedad o depresión de la HADS y variables como la edad, el nivel educativo y las comorbilidades.

Conclusiónlos hallazgos de este estudio ofrecen información novedosa e implícita sobre las consecuencias psiquiátricas adversas, la alta prevalencia de ansiedad y síntomas depresivos y la reducción de la calidad de vida entre los pacientes con condiciones comórbidas después de la pandemia de COVID-19.

The definition of anxiety in academic literature can sometimes lack clarity, despite the availability of accurate descriptions of its clinical manifestations.1 According to the American Psychological Association (APA), anxiety involves the anticipation of negative events, accompanied by physical sensations of tension and potentially dysphoria.2 Conversely, depression is a commonly observed affective disorder characterised by symptoms such as lethargy, decreased energy, agitation, melancholia, and suicidal tendencies.3 Recognising that comorbidities can impact health outcomes, particularly in relation to affective disorders like anxiety and depression, provides a fresh perspective for evaluating these conditions.

Numerous studies have investigated comorbidities between anxiety and depression. The presence of anxiety and depression alongside non-affective diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases, has been associated with poorer health outcomes and increased mortality rates. Specific illnesses have been extensively examined regarding the effects of anxiety and depression. Fond et al4 assessed the impact of anxiety and depression in patients with severe inflammatory bowel disease and reported a higher prevalence of these mental health disorders. Hinz et al5 also compared their relative prevalence in cancer patients and compared the results with those of the general population. Similarly, Linden et al6 found higher rates of depression and anxiety among women and individuals with haematological, lung, and gynaecological cancers.

The ongoing pandemic has a negative impact on the mental health of patients with comorbidities. There has been a 25% increase in the prevalence of anxiety and depression during the pandemic. This rise can be attributed to various stress factors, including limited access to healthcare, gaps in healthcare services, positive COVID-19 test results, and uncertainty and fear surrounding the outcomes of the pandemic.7,8 Earlier literature indicated that individuals with pre-existing conditions, women, and younger individuals have been most affected by the pandemic in terms of mental health.9 From this perspective, our study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of anxiety and depression, as well as the quality of life, among patients with chronic medical conditions in Amman, Jordan, in the post-pandemic era.

MethodsStudy design and settingThis was a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted from September 2022 to December 2022 among a convenient sample size of participants while attending the community pharmacies in Amman City, Jordan. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Human Research, Girne American University, Kyrenia, Northern Cyprus (Ref. no. 2020-21/001).

Study participants and samplingTo ensure generalisability and minimise selection bias, a three-stage sampling method based on population density (high, medium, and low) was achieved during the study. Five community pharmacies were conveniently selected from each of the 3 clusters, for a total of 15 pharmacies. Assuming a value of 95%; at the 5% significance level with an effect size of 0.920, the sample size was estimated at 70 participants. During the study period, a total of 215 participants were enrolled. However, 150 participants completed the entire survey, giving a response rate of nearly 70%. Participants older than 18 years suffering from chronic disease conditions and comorbidity and expressing willingness to take part in this study were included in the study while attending the community pharmacies. Based on earlier literature, the pandemic can potentially affect mental health and has contributed to elevated levels of anxiety and depression through various factors.15 Therefore, individuals who were currently infected and those with a history of COVID-19 were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included patients with pre-existing mental health conditions, and those who refused to participate or provided incomplete questionnaire responses were excluded from the study.

Questionnaire developmentThrough one-on-one interviews, the purpose of the study was explained to eligible participants who agreed to participate, and informed consent was obtained, ensuring voluntary participation with guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. A structured, self-administered questionnaire was administered to be completed by the respondent without an interviewer's assistance, which lasted approximately 15 min. The questionnaire was carefully developed based on extensive and comprehensive literature research, specifically tailored to meet the objectives of the current study. To ensure accuracy and appropriateness, the questionnaire underwent translation from English to Arabic and vice versa. The contents were reviewed and confirmed by 2 pharmacists and medical staff who were proficient in both languages. Additionally, a pre-test of the study was conducted on approximately 5% of the target sample to identify any ambiguities in the questionnaire items and to ensure the reliability of the data provided. The results of the pre-test were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Study variables and data collectionThe final version of the questionnaire is divided into 3 parts, including demographic data of the enrolled participants (age, gender, educational level, occupation status, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, types of chronic disease conditions, duration of chronic disease conditions, and number of current medication therapies). The second part regarding anxiety and depression prevalence was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).10 The Arabic version of the questionnaire was evaluated for validity and reliability by El-Rufaie and Absood. 11 The HADS is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 2 domains and 14 items. Participants rank their responses on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (extremely), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 42. Higher scores indicate greater levels of anxiety or depression. The scores are divided as follows: normal (0–7), borderline abnormal/mild (8–10), and abnormal/moderate to severe (11–21).

The third part of the questionnaire assessed the quality of life (QoL) in patients with chronic diseases and comorbidity affected by anxiety and depression following the COVID-19 pandemic. This was measured using a reliable and validated Arabic version of the SF-36 QoL questionnaire.12,13 The SF-36 questionnaire consists of 36 questions divided into 8 domains, which are used to calculate 2 separate summary scales: the Physical Components Summary (PCS) and the Mental Components Summary (MCS). Each summary scale includes 4 subscales. Scores on the scales range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a better quality of life.

Statistical analysisStatistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) software for Windows (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA) version 23.0 and Microsoft Office Excel 2013 were used for data analysis. The mean, standard deviation, and median range were used to express numerical variables, while number and percentage were used to express categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was performed to assess significant differences among means. An unpaired t-test was used to assess the significant differences between the 2 means. The P-value was considered significant at <.05 and highly significant at ≤.01.

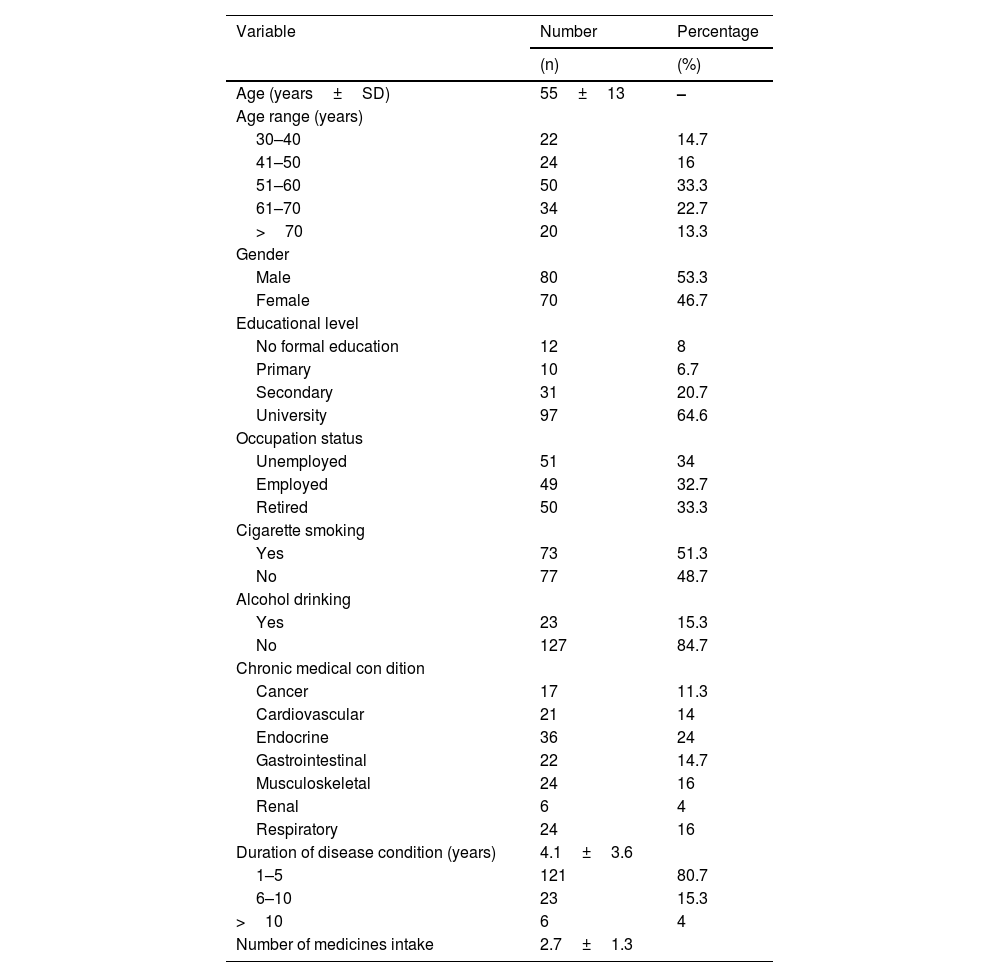

ResultsMost of the respondents were aged 51–60 years (33.3%) and followed by those aged 61–70 years (22.7%), with a mean age of 55±13 years. The majority of the enrolled participants were males (53.3%), had a university level (64.6%). Nearly an equal proportion of the study participants were unemployed and retired (34% and 33.3%, respectively). Most of the participants were smokers (51.3%). Endocrine disease conditions, particularly type 2 diabetes mellitus (24%), followed by an equal proportion of musculoskeletal and respiratory conditions (16%) were the most common chronic conditions encountered among the study participants. The mean duration of disease conditions was 4.1±3.6 years, and 80.7% had disease conditions lasting 1–5 years. A total of 385 medicines, with a mean of 2.7±1.3 per patient, were recorded in the present study. Patients receiving ≥4 medicines simultaneously (polypharmacy) were reported in 25.3% of the study participants (Table 1).

Demographic data of the participants.

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | |

| Age (years±SD) | 55±13 | – |

| Age range (years) | ||

| 30–40 | 22 | 14.7 |

| 41–50 | 24 | 16 |

| 51–60 | 50 | 33.3 |

| 61–70 | 34 | 22.7 |

| >70 | 20 | 13.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 80 | 53.3 |

| Female | 70 | 46.7 |

| Educational level | ||

| No formal education | 12 | 8 |

| Primary | 10 | 6.7 |

| Secondary | 31 | 20.7 |

| University | 97 | 64.6 |

| Occupation status | ||

| Unemployed | 51 | 34 |

| Employed | 49 | 32.7 |

| Retired | 50 | 33.3 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Yes | 73 | 51.3 |

| No | 77 | 48.7 |

| Alcohol drinking | ||

| Yes | 23 | 15.3 |

| No | 127 | 84.7 |

| Chronic medical con dition | ||

| Cancer | 17 | 11.3 |

| Cardiovascular | 21 | 14 |

| Endocrine | 36 | 24 |

| Gastrointestinal | 22 | 14.7 |

| Musculoskeletal | 24 | 16 |

| Renal | 6 | 4 |

| Respiratory | 24 | 16 |

| Duration of disease condition (years) | 4.1±3.6 | |

| 1–5 | 121 | 80.7 |

| 6–10 | 23 | 15.3 |

| >10 | 6 | 4 |

| Number of medicines intake | 2.7±1.3 |

Data presented as number (n), percentage (%), mean±SD.

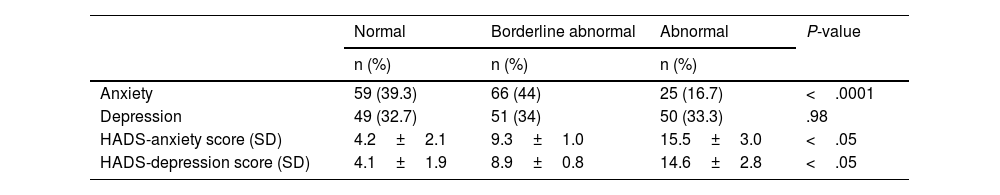

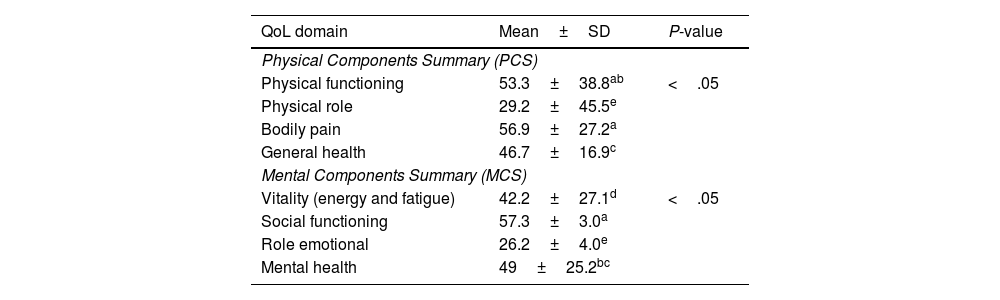

The anxiety and depression prevalence among the study participants is shown in Table 2. Most of the participants reported a significant borderline abnormal or mild anxiety (44%, P<.0001). Though not statistically significant, many of the respondents also reported borderline abnormal or mild depression (34%). Meanwhile, a statistically significant difference was found regarding the HADS anxiety and depression scores (P<.05, respectively). The assessment of quality of life (QoL) showed that the study participants reported a relatively poor QoL regarding all components of the PCS and MCS scales, particularly physical role (29.2±45.5) and emotional role (26.2±4.0) (P<.05), Table 3.

Prevalence of anxiety and depression among the participants.

| Normal | Borderline abnormal | Abnormal | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Anxiety | 59 (39.3) | 66 (44) | 25 (16.7) | <.0001 |

| Depression | 49 (32.7) | 51 (34) | 50 (33.3) | .98 |

| HADS-anxiety score (SD) | 4.2±2.1 | 9.3±1.0 | 15.5±3.0 | <.05 |

| HADS-depression score (SD) | 4.1±1.9 | 8.9±0.8 | 14.6±2.8 | <.05 |

Normal (0–7), borderline abnormal/mild (8–10), abnormal/moderate to severe (11–21).

Data presented as number (n), percentage (%) and mean±SD.

Significant at P≤.05.

Quality of life (QoL) assessment among the participants.

| QoL domain | Mean±SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Components Summary (PCS) | ||

| Physical functioning | 53.3±38.8ab | <.05 |

| Physical role | 29.2±45.5e | |

| Bodily pain | 56.9±27.2a | |

| General health | 46.7±16.9c | |

| Mental Components Summary (MCS) | ||

| Vitality (energy and fatigue) | 42.2±27.1d | <.05 |

| Social functioning | 57.3±3.0a | |

| Role emotional | 26.2±4.0e | |

| Mental health | 49±25.2bc | |

Data presented as mean±SD.

Means with a different letter are significantly different (P<.05).

Significant at P≤.05.

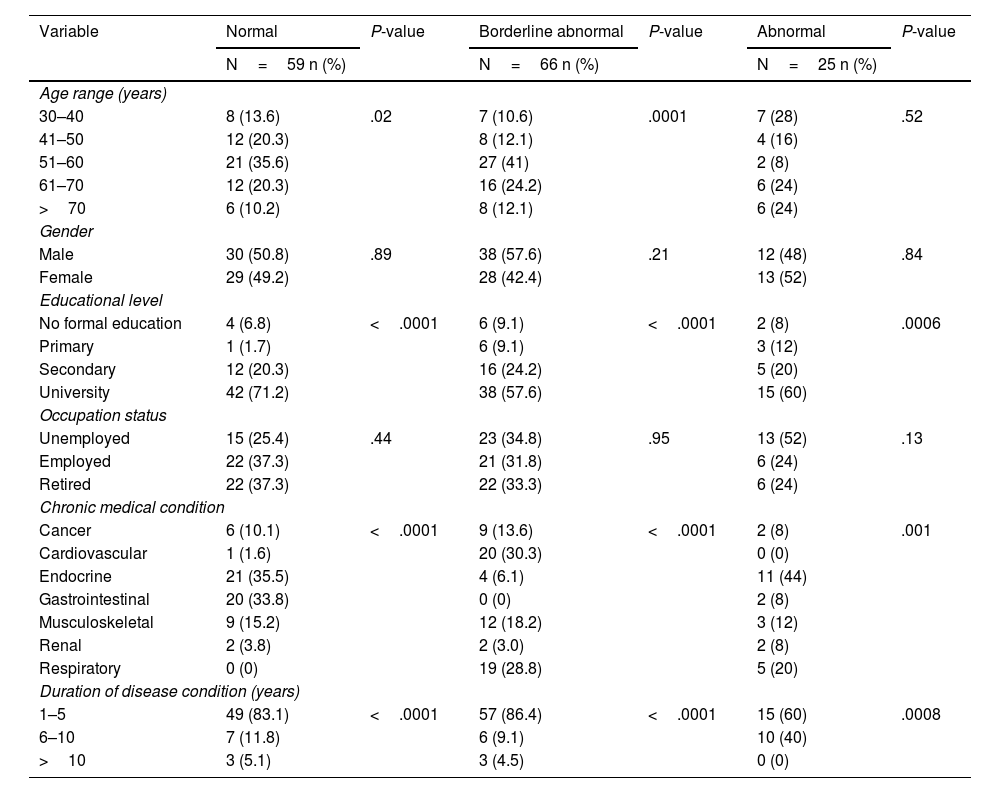

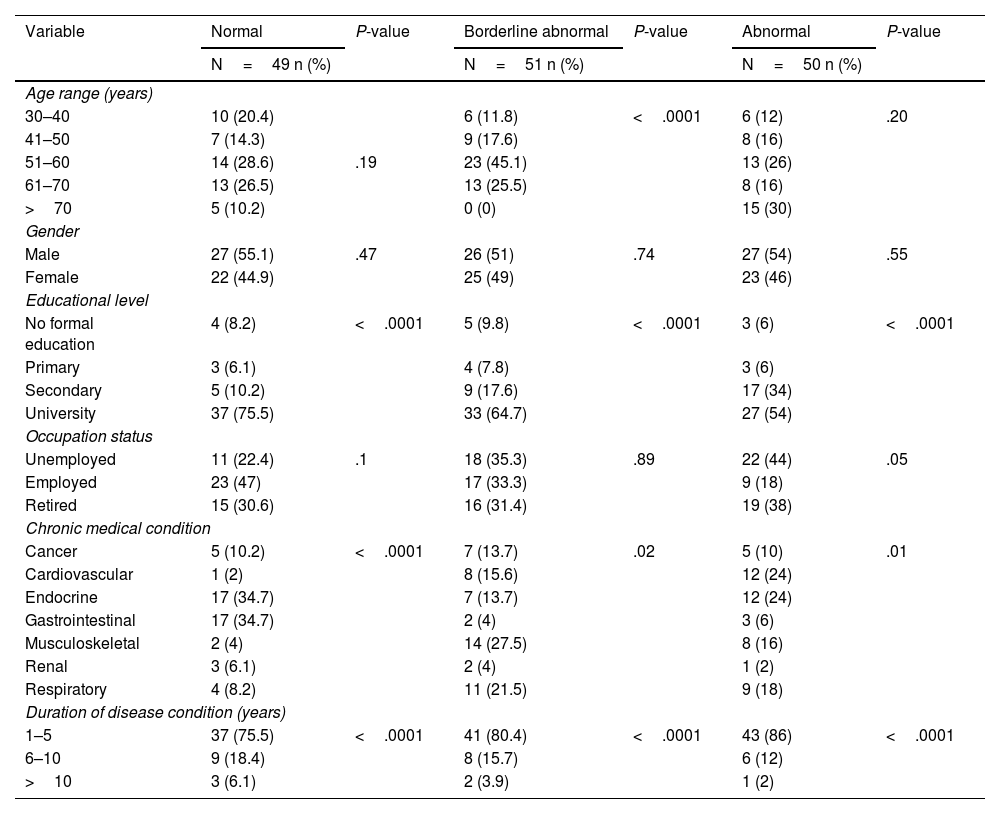

Stratifying the HADS-anxiety and demographic data is shown in Table 4. Our study found a significant findings between age range and the HADS-anxiety score (normal/ borderline abnormal) (P=.02; P=.0001, respectively), university educational level and the normal (P<.0001), borderline abnormal (P<.0001) and abnormal scores (P=.0006), chronic medical condition and the normal (P<.0001), borderline abnormal (P<.0001) and abnormal scores (P=.001) and duration of disease condition and the normal (P<.0001), borderline abnormal (P<.0001) and abnormal scores (P=.0008). Similarly, the HADS-depression and demographic characteristics among the study participants revealed a statistically significant results between age of the patients and the borderline abnormal (P<.0001), university educational level and the normal (P<.0001), borderline abnormal (P<.0001) and abnormal scores (P<.0001), chronic medical condition and the normal (P<.0001), borderline abnormal (P=.02) and abnormal scores (P=.01) and duration of disease condition and the normal (P<.0001), borderline abnormal (P<.0001) and abnormal scores (P<.0001), as shown in Table 5.

Association between HADS-anxiety and demographic data of the participants.

| Variable | Normal | P-value | Borderline abnormal | P-value | Abnormal | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=59 n (%) | N=66 n (%) | N=25 n (%) | ||||

| Age range (years) | ||||||

| 30–40 | 8 (13.6) | .02 | 7 (10.6) | .0001 | 7 (28) | .52 |

| 41–50 | 12 (20.3) | 8 (12.1) | 4 (16) | |||

| 51–60 | 21 (35.6) | 27 (41) | 2 (8) | |||

| 61–70 | 12 (20.3) | 16 (24.2) | 6 (24) | |||

| >70 | 6 (10.2) | 8 (12.1) | 6 (24) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 30 (50.8) | .89 | 38 (57.6) | .21 | 12 (48) | .84 |

| Female | 29 (49.2) | 28 (42.4) | 13 (52) | |||

| Educational level | ||||||

| No formal education | 4 (6.8) | <.0001 | 6 (9.1) | <.0001 | 2 (8) | .0006 |

| Primary | 1 (1.7) | 6 (9.1) | 3 (12) | |||

| Secondary | 12 (20.3) | 16 (24.2) | 5 (20) | |||

| University | 42 (71.2) | 38 (57.6) | 15 (60) | |||

| Occupation status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 15 (25.4) | .44 | 23 (34.8) | .95 | 13 (52) | .13 |

| Employed | 22 (37.3) | 21 (31.8) | 6 (24) | |||

| Retired | 22 (37.3) | 22 (33.3) | 6 (24) | |||

| Chronic medical condition | ||||||

| Cancer | 6 (10.1) | <.0001 | 9 (13.6) | <.0001 | 2 (8) | .001 |

| Cardiovascular | 1 (1.6) | 20 (30.3) | 0 (0) | |||

| Endocrine | 21 (35.5) | 4 (6.1) | 11 (44) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 20 (33.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | |||

| Musculoskeletal | 9 (15.2) | 12 (18.2) | 3 (12) | |||

| Renal | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.0) | 2 (8) | |||

| Respiratory | 0 (0) | 19 (28.8) | 5 (20) | |||

| Duration of disease condition (years) | ||||||

| 1–5 | 49 (83.1) | <.0001 | 57 (86.4) | <.0001 | 15 (60) | .0008 |

| 6–10 | 7 (11.8) | 6 (9.1) | 10 (40) | |||

| >10 | 3 (5.1) | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0) | |||

Normal (0–7), borderline abnormal/mild (8–10), abnormal/moderate to severe (11–21); Significant at P≤.05.

Association between HADS-depression and demographic data of the participants.

| Variable | Normal | P-value | Borderline abnormal | P-value | Abnormal | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=49 n (%) | N=51 n (%) | N=50 n (%) | ||||

| Age range (years) | ||||||

| 30–40 | 10 (20.4) | 6 (11.8) | <.0001 | 6 (12) | .20 | |

| 41–50 | 7 (14.3) | 9 (17.6) | 8 (16) | |||

| 51–60 | 14 (28.6) | .19 | 23 (45.1) | 13 (26) | ||

| 61–70 | 13 (26.5) | 13 (25.5) | 8 (16) | |||

| >70 | 5 (10.2) | 0 (0) | 15 (30) | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 27 (55.1) | .47 | 26 (51) | .74 | 27 (54) | .55 |

| Female | 22 (44.9) | 25 (49) | 23 (46) | |||

| Educational level | ||||||

| No formal education | 4 (8.2) | <.0001 | 5 (9.8) | <.0001 | 3 (6) | <.0001 |

| Primary | 3 (6.1) | 4 (7.8) | 3 (6) | |||

| Secondary | 5 (10.2) | 9 (17.6) | 17 (34) | |||

| University | 37 (75.5) | 33 (64.7) | 27 (54) | |||

| Occupation status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 11 (22.4) | .1 | 18 (35.3) | .89 | 22 (44) | .05 |

| Employed | 23 (47) | 17 (33.3) | 9 (18) | |||

| Retired | 15 (30.6) | 16 (31.4) | 19 (38) | |||

| Chronic medical condition | ||||||

| Cancer | 5 (10.2) | <.0001 | 7 (13.7) | .02 | 5 (10) | .01 |

| Cardiovascular | 1 (2) | 8 (15.6) | 12 (24) | |||

| Endocrine | 17 (34.7) | 7 (13.7) | 12 (24) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 17 (34.7) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | |||

| Musculoskeletal | 2 (4) | 14 (27.5) | 8 (16) | |||

| Renal | 3 (6.1) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | |||

| Respiratory | 4 (8.2) | 11 (21.5) | 9 (18) | |||

| Duration of disease condition (years) | ||||||

| 1–5 | 37 (75.5) | <.0001 | 41 (80.4) | <.0001 | 43 (86) | <.0001 |

| 6–10 | 9 (18.4) | 8 (15.7) | 6 (12) | |||

| >10 | 3 (6.1) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2) | |||

Normal (0–7), borderline abnormal/mild (8–10), abnormal/moderate to severe (11–21); Significant at P≤.05.

The prevalence of depression and anxiety has been increasing due to their detrimental impact on mental health. Comorbidities are known to be influential factors associated with worsened mental well-being. Moreover, COVID-19 has been linked to poor prognoses, particularly in patients with comorbid conditions. Existing literature indicates that individuals with underlying conditions tend to experience more severe illness during the pandemic compared to those without such conditions.14 Furthermore, the global pandemic has contributed to elevated levels of anxiety and depression through various factors, including lockdown measures, unemployment, job insecurity, and economic losses.15 Meanwhile, access to accurate and up-to-date health information, such as information on treatment options and preventive measures, has been associated with reduced psychological impact.16 Our study revealed the clinical consequences of pandemic-induced stress and quarantine measures on our sample population. A significant proportion of respondents with chronic diseases reported a high level of psychological vulnerability, manifested as a high prevalence of depression and anxiety, along with a decline in their quality of life due to the distress caused by the pandemic.

Our findings are consistent with a previous study conducted in China by Wang et al16 reported that over half of the respondents experienced a moderate or severe psychological impact due to the outbreak. Similarly, Sayeed et al17 found that patients with comorbid diseases reported anxiety symptoms in 59% of cases and depression symptoms in 71.6% of cases during the pandemic. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in our study was higher compared to results reported in other countries. A study by Adhikari et al18 found an anxiety prevalence of 8.0% and a depression prevalence of 11.2% among home-isolated COVID-19 patients. However, our findings were lower than the prevalence estimates of anxiety and depression symptoms reported among patients with chronic disease conditions in Nepal,18 Egypt,19 and Iran.20 Furthermore, a meta-analysis study reported anxiety and depression rates of 45% and 47%, respectively, among COVID-19 patients.21 The effects of the pandemic extend beyond clinical outcomes, such as mortality and morbidity, and encompass subjective measures, including quality of life. The decline in quality of life and mental health can be attributed to the social and economic impacts resulting from the pandemic. In our study, participants exhibited relatively poor quality of life across all components of the Physical Components Summary (PCS) and Mental Components Summary (MCS) scales, with significant impairment observed in physical and emotional roles. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the significant impact of the pandemic on quality of life in COVID-19 patients.22,23

When stratifying the HADS scores with the demographic characteristics of the participants, significant findings were found with age, educational level, and chronic medical conditions. Meanwhile, older age and the presence of chronic medical conditions, which are known risk factors for COVID-19 complications, were associated with a higher risk of anxiety and depression symptoms. This finding is consistent with a study by Sayeed et al,17 which also reported significant associations between chronic disease conditions and mental health outcomes. Similarly, the study conducted by Adhikari et al18 reported a higher prevalence of anxiety among participants with comorbid conditions (P=.03). The elevated rates of anxiety and depression among individuals with comorbidities may be attributed to their higher risk of severe illness and mortality from COVID-19. It is possible that the participants in our study, who had a higher education level- were more aware of the risks associated with the pandemic, leading to increased levels of anxiety.24,25 This finding is consistent with a meta-analysis study that showed participants with higher education levels had a higher prevalence of anxiety due to easier access to information compared to the public.26 Moreover, public perception regarding disruptions in the healthcare system during the pandemic and the belief that individuals with chronic diseases are more vulnerable may contribute to the heightened rates of anxiety and depression.27,28 Therefore, it is crucial to provide accurate and appropriate information about the pandemic to reduce unnecessary fear and anxiety related to infection, positive test results, isolation, and stigma associated with COVID-19.29,30

The study has several limitations. First, the findings may not be generalisable to the broader population due to a relatively small sample size as the participants were enrolled in a single province, Amman City. Second, the absence of a control group limits the ability to understand the changes in anxiety and depression associated with the pandemic. Third, the study relied on self-report measures, which may introduce recall bias. Fourth, while the study excluded patients with pre-existing mental health conditions, the assessment of psychiatric history was not conducted. Lastly, patients' comorbidity status was self-reported, which may have led to underestimation as some individuals may have had multiple underlying conditions.

ConclusionThe findings of this study offer valuable insights into the psychiatric consequences experienced by patients with comorbidities post-COVID-19 pandemic. The study reveals a high prevalence of anxiety and depression, accompanied by a decline in quality of life. These findings emphasise the need for heightened psychiatric awareness and targeted clinical interventions for individuals who are more vulnerable, particularly those with underlying medical conditions, following the COVID-19 pandemic. By recognising and addressing the unique challenges faced by this population, healthcare professionals can provide appropriate support and interventions to mitigate the negative impact on their mental well-being.

FundingNo specific funding was received.

Authorship contribution statementAA conceived of the study. AA, DK, and OA reviewed the literature, conducted the quality assessment, and extracted the data. AA developed the methods, supported the data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. DK and OA reviewed and collected the data. AA was the project manager and advisor on the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.