Suicide is the first cause of external death in Spain. International studies show frequent and varied health contacts in the months prior to suicide. There are hardly any studies on that phenomenon in this country.

ObjectiveTo analyze health care use in the year prior to suicide between 2010 and 2018 in the Basque Country, as well as pharmacological prescriptions and psychiatric diagnoses received.

MethodsRetrospective descriptive study with all suicides registered by the Basque Institute of Legal Medicine (BILM) between 2010 and 2018. The records of the BILM and the Basque Health Service (Osakidetza) were cross-checked.

Results1526 suicides were analyzed. 74% had health contacts in the previous year. The use was higher in women (p<0.05) and in older ages (p<0001). Primary care was the most used specialty (58.8% the previous year and 7.1% the previous week), followed by Hospital Emergencies (50.3% and 10.2%) and Outpatient Medical Specialties (49% and 11.6%), especially Radiology. Outpatient psychiatry only contacted 29.6% that year, although it had the highest average number of visits (15.1 SD22.6). The most frequent diagnostic category among psychiatric patients was F30–39 (26.7%), with differences between sexes and ages. 49.7% received psychotropic drugs.

ConclusionsThe results are aligned with international evidence, which they also extend, and reinforce the need to extend prevention beyond psychiatric services. It seems advisable to increase proactivity in the search for risk by sensitizing and training different professional profiles, but also to work from non-health settings to improve assistance to highly vulnerable profiles (young men) with low health links.

Suicide is the leading cause of external death in Spain and has been recognized as one of the public health challenges.1 In people who die by suicide, the risk of presenting physical and mental pathologies is significantly higher2–4 and we also know that they are very frequent users of the health care system5,6 which makes the health care setting a key environment for identifying the risk and enabling effective prevention.1,7 The relationship between suicide and mental disorders has been more clearly demonstrated8 and the treatment of these disorders is one of the most effective suicide prevention measures7,9,10 however, international studies show an under-diagnosis and under-treatment of mental pathology in people who die by suicide.5

The information available in Spain on the use of health services prior to suicide or on the diagnoses and treatments received during this period is very scarce11,12 and requires extrapolation of information from health systems and cultural environments with different characteristics. The availability of specific and detailed data would help to design selective prevention strategies with a probable impact on the number of suicides.

The aim of this study is to analyze healthcare use in the year prior to suicide in cases registered between 2010 and 2018 in the Basque Country (Spain), as well as the prescriptions and psychiatric diagnoses received by these individuals.

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective descriptive study. All suicides in persons>18 years of age registered by the Basque Institute of Legal Medicine (BILM) after forensic autopsy between 2010 and 2018 were included. Data for the study were obtained from cross-referencing the BILM database and the Electronic Health Record (EHR) of the Basque Health Service (Osakidetza). Information on the use of hospital emergency departments was limited to the period 2015–2018. Univariate descriptive analyses and crosstabs between variables were performed using the chi-square test to identify their association with suicide. The cumulative percentage of individuals who had contacted different services and specialties in the year prior to suicide was examined. Drug prescription and psychiatric diagnoses recorded in the EHR were analyzed. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Basque Country.

ResultsThe total sample included a total of 1526 suicide cases. A total of 73.6% were men. The mean age was 56 years (SD 18.7) and the most frequent suicide method was precipitation (41.1%).

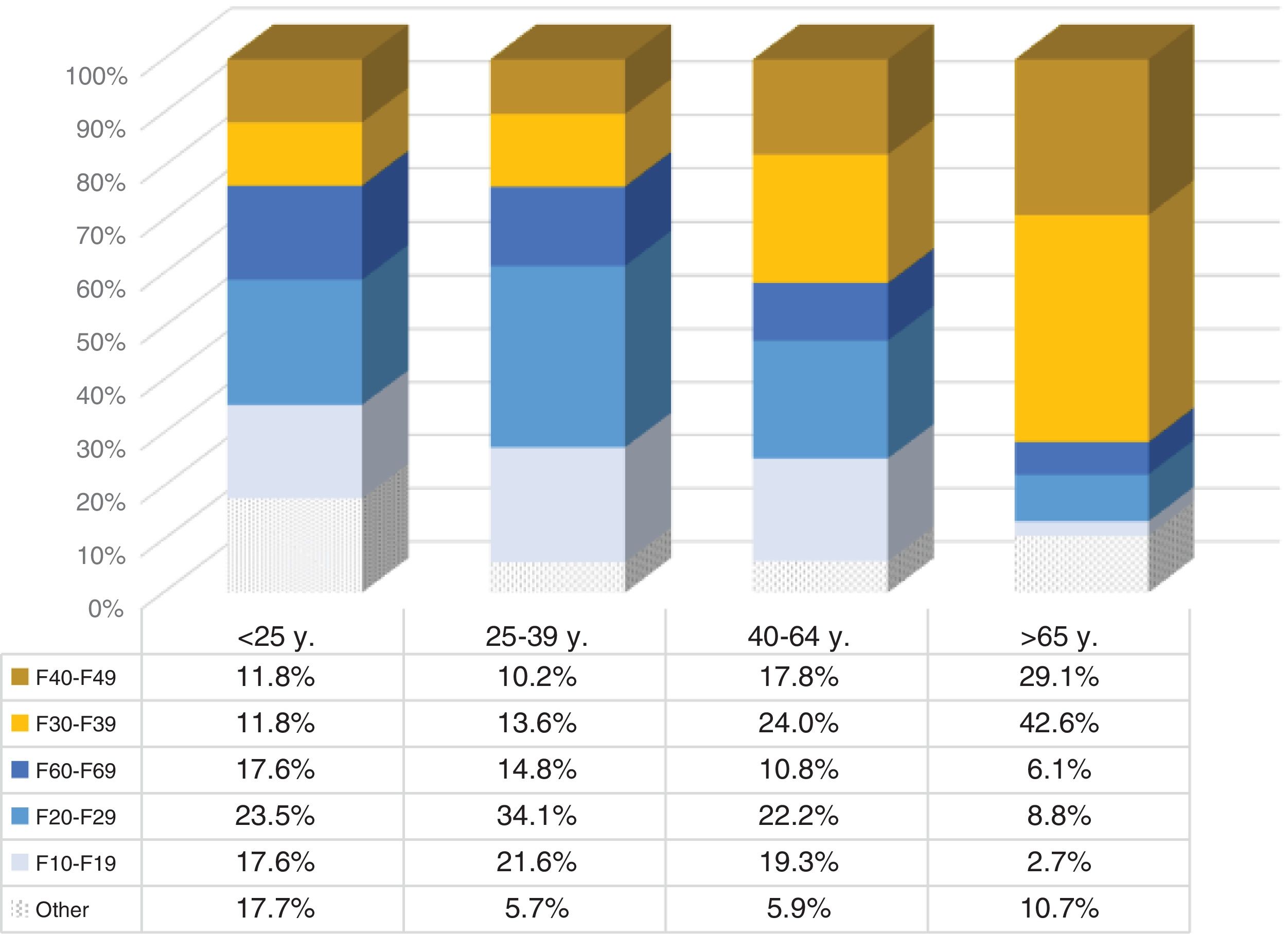

Use of health services in the year prior to suicide74.0% had at least one appointment with the health system in the year prior to their suicide. 48.6% made at least one contact in the previous month and 30.3% in the previous week. The percentage of women who made contact was significantly higher and progressive increases in the percentage of users were observed with age (Table 1).

Percentage of cases with ≥1 contact with the public health system in the year prior to suicide and mean number of contacts by service type.

| Any | PC | HEDa | OMH-O | MH-O | OMH-Ha | MH-Ha | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12m | 1m | 1w | 12m | 1m | 1w | 12m | 1m | 1w | 12m | 1m | 1w | 12m | 1m | 1w | 12m | 1m | 12m | 1m | |

| Total % | 74.0 | 48.6 | 30.3 | 58.8 | 18.2 | 7.1 | 50.3 | 23.2 | 10.2 | 49 | 22.7 | 11.6 | 29.6 | 18.2 | 9.9 | 17.6 | 5 | 11.8 | 3.2 |

| Total n | 1130 | 742 | 462 | 897 | 278 | 108 | 340 | 157 | 69 | 748 | 346 | 177 | 451 | 278 | 151 | 269 | 77 | 180 | 49 |

| Men (%) | 72.4 | 46.2 | 27.9 | 57 | 16.8 | 7.2 | 46.4 | 19 | 7.8 | 45.7 | 21.1 | 10.3 | 25.2 | 16 | 8.6 | 18.3 | 5.7 | 9.9 | 2.2 |

| n | 808 | 516 | 311 | 636 | 188 | 80 | 232 | 95 | 39 | 518 | 239 | 117 | 285 | 181 | 97 | 204 | 64 | 110 | 25 |

| Women (%) | 78.5 | 55.1 | 36.8 | 63.7 | 22 | 6.8 | 61 | 35 | 16.9 | 54.5 | 25.4 | 14.2 | 39.3 | 23 | 12.8 | 15.9 | 3.2 | 17.1 | 5.9 |

| n | 322 | 226 | 151 | 261 | 90 | 28 | 108 | 62 | 30 | 230 | 107 | 60 | 166 | 97 | 54 | 65 | 13 | 70 | 24 |

| p-Value | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.05 | n.s | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 | n.s | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | n.s | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| <25 y. (%) | 42.6 | 30.9 | 19.1 | 35.3 | 11.8 | 2.9 | 27.3 | 15.2 | 12.1 | 20.3 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 20.3 | 14.5 | 7.2 | 4.4 | 0 | 10.3 | 0 |

| n | 29 | 21 | 13 | 24 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 25–39 y. (%) | 64.1 | 41.3 | 24.2 | 46.6 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 35.3 | 15.3 | 7.1 | 35.6 | 14.7 | 8 | 30.7 | 21.3 | 9.8 | 4 | 0.9 | 14.3 | 3.1 |

| n | 143 | 92 | 54 | 104 | 25 | 8 | 30 | 13 | 6 | 80 | 33 | 18 | 69 | 48 | 22 | 9 | 2 | 32 | 7 |

| 40–64 y. (%) | 73.4 | 45.3 | 29.4 | 57.5 | 15.3 | 5.8 | 46.5 | 19 | 9.5 | 41.9 | 16.5 | 8.3 | 34.6 | 22.4 | 13.4 | 12.1 | 1.7 | 15.6 | 4.4 |

| n | 522 | 322 | 209 | 409 | 109 | 41 | 147 | 60 | 30 | 307 | 121 | 61 | 253 | 164 | 98 | 86 | 12 | 111 | 31 |

| >65 y. (%) | 83.2 | 58.6 | 35.5 | 68.7 | 26 | 10.9 | 63.4 | 32.5 | 11.9 | 65.6 | 35.2 | 17.6 | 21.7 | 10.6 | 4.9 | 32.6 | 12 | 5.7 | 2.1 |

| n | 436 | 307 | 186 | 360 | 136 | 57 | 154 | 79 | 29 | 347 | 186 | 93 | 115 | 56 | 26 | 171 | 63 | 30 | 11 |

| p-Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | n.s | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | n.s |

| Number of contacts mean (ED) | 2.7 (2.2) | 1.3 (0.6) | 2.7 (2.9) | 1.3 (0.7) | 9.2 (13.2) | 2.8 (3.4) | 15.1 (22.7) | 2.9 (3.4) | |||||||||||

List of acronyms: PC: primary care; HED: Hospital Emergency Department; OMH-O: outpatient consultation in a specialty other than Mental Health; MH-O: Outpatient Mental Health consultation; OMH-H: Hospital admission except for Mental Health; MH-H: Hospital admission for Mental Health; m: month; w: week; y: years old.

Primary care (PC) was the specialty contacted by a higher proportion of these individuals, with figures ranging from 58.8% (previous year) to 7.1% (previous week). This was followed by hospital emergency departments, which were contacted by 50.2% in the previous year and 10.2% in the last week, and by the non-psychiatric outpatient specialties as a whole (49% and 11.8%). Radiodiagnostics was by far the specialty that contacted the most at-risk patients in their last weeks of life. In total, it visited 168 patients in their last month and 92 in their last week, figures that correspond to 11% and 6% of all suicide cases recorded, respectively. This is followed by neurology and gastroenterology, although with clearly lower figures.

On the other hand, 29.6% were seen in an outpatient mental health service (MH-O) in the 12 months prior to suicide and 9.9% in the last week. In contrast to other outpatient specialties, people aged 25–64 years and especially those aged 40–64 years contacted more. MH-O made the highest number of visits to these patients, with an average of 15.1 appointments (SD 22.6) in the previous year and 2.8 (SD3.4) in the last month.

Regarding hospitalization, 17.6% had a non-psychiatric admission in the previous year and 5% in the previous month. 40% of these admissions were to internal medicine and no differences were observed between sexes. For psychiatric admissions, the figures ranged from 11.8% (previous year) to 3.2% (previous month). As was the case with outpatient mental health resources, use was higher among those aged 40–64 years.

Pharmacological prescriptions and psychiatric diagnoses57.8% received at least one pharmacological prescription. Group N of the ATC classification (Nervous System) was the most prescribed overall (49.7% received ≥1 prescription) and also in all age and sex groups. It was followed by alimentary tract or A Group (30.4%) and cardiovascular or C Group (26.4%) drugs. The most prescribed Subgroup N was N05 including sedative-hypnotics (43.8% received them), followed by N06 including antidepressants (29.4%) and N02 opioid-analgesics (23%). The mean number of drugs N prescribed was 5.0 (SD 3.1) in women and 3.0 (SD 2.3) in men.

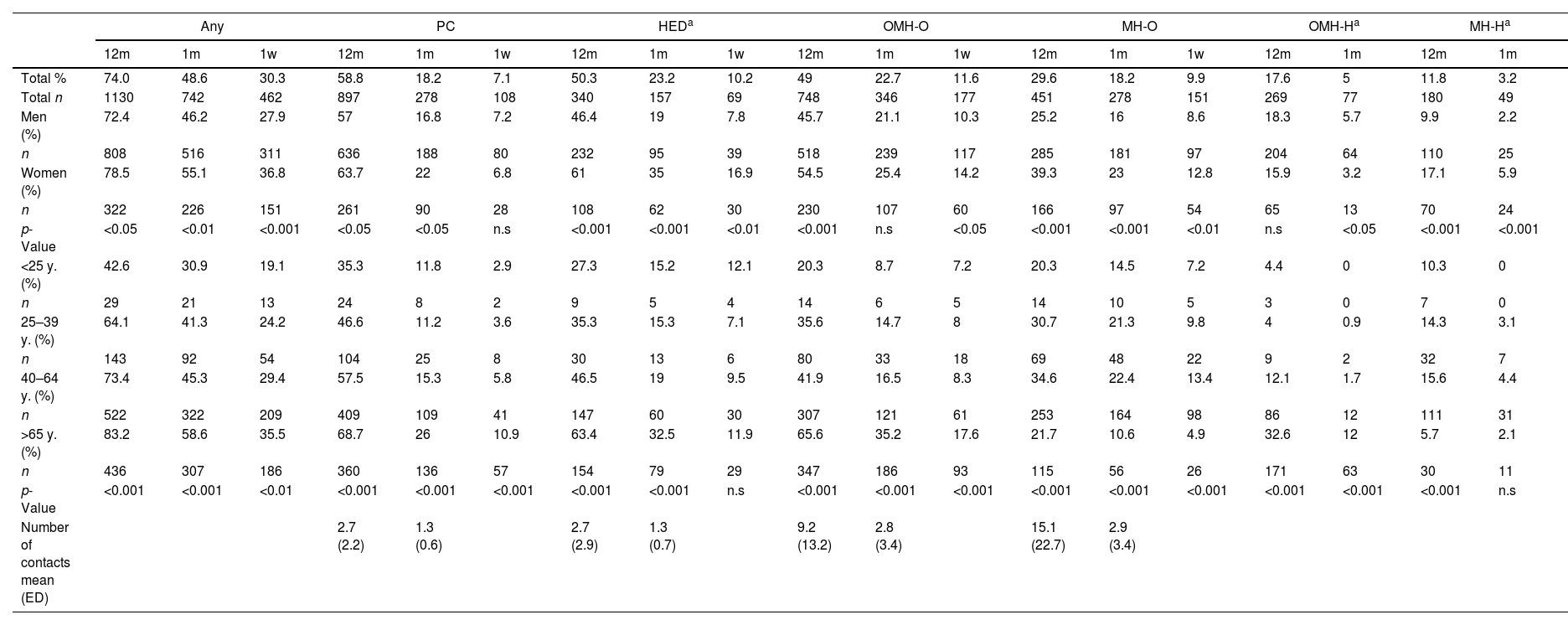

The psychiatric diagnoses made in the MH-O and PC resources were also reviewed. In MH-O the most frequent ICD-10 categories were F30–39 (26.7% of diagnoses), F20–29 (20.7%) or F40–49 (19.3%) and the most common specific diagnoses were F32-Depressive Episode (15.5%), F20-Schizophrenia (11.9%) and F48-Other (11.1%). However, differences were observed between ages and sexes: among those under 40 years of age, the most frequent category was F20–F29, followed by F10–19 and F60–F69, and in men F20–F29 predominated (25.3%; Fig. 1). On the other hand, 18.6% received a diagnosis of mental disorder in PC, with no significant differences between sexes or ages. The most frequent disorders were anxiety and somatoform (25.1%), adaptive and stress reaction disorders (22.1%) and Substance use disorders (19.2%). A code for “suicidal ideation” was recorded in 2.8%.

Distribution of psychiatric diagnoses (ICD10) made in patients seen in MH-O services, by age group (*). The list of diagnostic categories include: F10–F19 Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39 Mood [affective] disorders; F40–F49 Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F60–F69 Disorders of adult personality and behavior. (*) Each patient could receive no diagnosis, one diagnosis or more than one diagnosis.

The results are aligned with the available evidence, which they also extend, and show a high and varied pre-suicide health care frequentation in our country. One in three cases consulted in their last week of life, which opens an important window of opportunity for prevention.

When comparing the data with the international literature, there is less contact with PC in our study (review studies reflect contacts in 80%), perhaps due to a greater role of other specialties in the management of a physical pathology whose presence is very frequent in suicide and which could act as a key risk factor for this outcome.2–5 In this sense also points out the leading role of radiology, a finding to our knowledge unpublished and that could be justified by the cross-cutting nature of this specialty associated with the presence of a variety of medical pathologies.

The percentages of MH-O use are similar to or somewhat higher than those reported in the literature6,12–14; however, they are worryingly low considering that MH would be the specialty most qualified for suicide prevention. This data, together with the low percentage of psychiatric diagnoses received in PC or the percentage of prescription of psychotropic drugs (as a “proxy” for psychiatric diagnosis) would suggest an under-diagnosis of mental pathology in these patients.7

As limitations, the absence of a control group design prevents us from concluding on the differential behavior of the people who committed suicide in relation to the patients as a whole. On the other hand, we know that a percentage of suicides are not recorded and this phenomenon could be greater in countries such as ours. Moreover, the data used come from a specific BILM registry and not from official data. However, some studies suggest that forensic sources would better reflect the epidemiological magnitude of suicide15 as they would avoid losses of cases in data transfer. In addition, comparison with official data showed minimal deviation in the number of cases.

ConclusionsThe results confirm the potential of our healthcare system as a whole to contribute to suicide prevention and therefore reinforce the need to extend these efforts beyond psychiatry, especially to PC and hospital emergency departments, but without forgetting medical specialties. It seems advisable to increase proactivity in the search for suicidal risk by sensitizing and training different professional profiles in the health system, and perhaps also by implementing selective screening procedures in PC or hospital emergency departments for non-psychiatric clinical profiles at higher risk. Finally, the lesser link with the health system identified in specific highly vulnerable profiles, generally men and especially the youngest, suggests the convenience of working from non-health resources (labor, social, etc.) to improve the identification and referral of those who may need it.

Sources of fundingThe present work has been funded by the Department of Health of the Basque Government (Grant 2019111020).

Conflicts of interestNo conflict of interest for this manuscript.

Dr. Gonzalez-Pinto has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Alter, Angelini, Novartis, Rovi, Takeda, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), the Ministry of Science (Carlos III Institute), the Basque Government, and the European Framework Program of Research.

Dr. Gabilondo has received grants or served as consultant for the Basque Department of Health, the European Commission (Health Program) and Janssen-Cilag.

![Distribution of psychiatric diagnoses (ICD10) made in patients seen in MH-O services, by age group (*). The list of diagnostic categories include: F10–F19 Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39 Mood [affective] disorders; F40–F49 Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F60–F69 Disorders of adult personality and behavior. (*) Each patient could receive no diagnosis, one diagnosis or more than one diagnosis. Distribution of psychiatric diagnoses (ICD10) made in patients seen in MH-O services, by age group (*). The list of diagnostic categories include: F10–F19 Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use; F20–F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–F39 Mood [affective] disorders; F40–F49 Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; F60–F69 Disorders of adult personality and behavior. (*) Each patient could receive no diagnosis, one diagnosis or more than one diagnosis.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/29502853/unassign/S2950285324000310/v1_202405290422/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)