An accurate cytohistologic diagnosis is important to avoid overtreatment of cervical intraepithelial lesions. The three-tiered Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) classification, grades 1, 2 and 3, despite poor agreement among pathologists in diagnosing CIN2, is still being used. The College of American Pathologists recommended an alternative two-tiered classification that has not yet been universally accepted.

We review the diagnostic results of 286 biopsies performed by three pathologists using haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and p16 to establish the level of agreement among the readers.

Agreement between pathologists in diagnosing CIN2 with H&E was around 45% and improved to 86.7% when interpreting p16 stained biopsies without H&E; agreement with pathologist 3 was lower, around 60%.

Discrepant results from one pathologist when assessing p16 highlights the decisive influence of individual criteria. P16 has shown to improve agreement between pathologists with previous good agreement, but did not correct it for the third pathologist.

In equivocal cases, protein p16 is a useful conjunctive tool for a histologic diagnosis.

Un diagnóstico citohistológico preciso es importante en las neoplasias intraepiteliales de cérvix (CIN) para evitar sobretratamientos. La clasificación de las lesiones en 3 grados (CIN1-2 y 3) utilizada por los patólogos demuestra grados de concordancia bajos, sobre todo para el diagnóstico de CIN2. El Colegio Americano de Patólogos recomienda la utilización de una clasificación dicotómica alternativa, clasificando las lesiones solo en alto o bajo grado, pero esta clasificación no está totalmente aceptada.

Nosotros hemos revisado el diagnóstico de 286 biopsias de cérvix, por 3 patólogos, utilizando hematoxilina-eosina (H&E) y p16, para establecer el grado de concordancia entre los 3, utilizando las 2 clasificaciones diagnósticas. La concordancia entre los patólogos en el diagnóstico de CIN2 solo con H&E ronda el 45% y mejora alcanzando el 73,9% cuando se interpretan las biopsias junto con p16.

El resultado discrepante de un patólogo cuando se apoya en la tinción con p16 pone de manifiesto la importancia de la subjetividad en la interpretación. P16 ha mostrado mejorar la concordancia entre patólogos, que ya tenían una concordancia mejor previamente, pero no sirve de mejora para el tercer patólogo.

En conclusión, el uso de p16 debería limitarse a los casos equívocos, e interpretarse junto con la H&E, pero es necesario un entrenamiento específico.

In 1999, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection was recognized as the causative agent of cervical cancer.1 Since then, many advances have been made in the diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer precursory lesions and incidence and mortality have considerably decreased, as recorded in the registries.2 In 2018, the WHO claimed that cervical cancer could be eradicated.3

In both Gynaecology and Pathology Departments, a considerable amount of financial and human resources are devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of precursory lesions. Screening programmes for cervical cancer, female breast cancer and colorectal cancer have been implemented in Public Health programmes for years now in developed countries.4 It is therefore of utmost importance to reinforce effectiveness and efficiency (cost/benefit) and address a recent finding in cervical cancer screening,5 distress in women requiring more or less frequent follow-up examinations.

The histological classification of precursory lesions has been changing ever since 1969 when Govan graded dysplasia into mild, moderate and severe.6 In 1983 Richart proposed the CIN classification with grades 1, 2 and 37 for dysplasia affecting less than one third of the epithelium thickness (CIN1); more than one third, but less than two thirds (CIN2); and more than two thirds (CIN3). This classification is still nowadays in use in many departments despite the fact that in 2012 the College of American Pathologists (CAP) along with other Scientific Societies convened the LAST8 Project with recommendations to unify terminology for HPV-associated lesions of the lower genital tract in an effort to clarify and establish a two-tiered classification: low-grade or high-grade lesions.

The need for a new classification is based on contrasted evidence of poor agreement among pathologists when diagnosing CIN2: the series reflects an agreement of around 40%.9,10

As it has been clinically observed that 90% of CNI1 lesions recur, LAST describes these lesions as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and recommends conservative management; CIN3 lesions tend to progress to invasive cancer, so LAST describes them as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) and recommends treatment.8 But what happens to CIN2 lesions? It has been observed that 64% will recur and that diagnostic agreement is low among pathologists,9–12 but even so LAST classifies CIN2 as high-grade and recommends treatment. For equivocal cases, tumour suppressor protein p16,13 a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A protein, should be used as an adjunct to the diagnosis. In normal cells overexpression of p16 protein results in cell cycle arrest.14 When high-risk HPV E7 oncogene, according to Cuzick's15 classification, is integrated in the genome of cervical squamous epithelial cells, it inhibits p16 and triggers an uncontrolled cellular proliferation.14 Overexpression of p16 can be detected by immunohistochemistry and thus overexpression of p16 in a cervical histological specimen indicates viral integration.16

From these findings, the LAST Project recommends classifying p16-positive CIN2 specimens as HSIL and p16-negative CIN2 specimens as LSIL.

Our study endpoint is to review if adding a consecutive p16-stained slice to haematoxylin–eosin (H&E) stains improves agreement between pathologists in the diagnosis of small cervical biopsies.17–22

MaterialsAll cervical biopsies diagnosed as CIN2 in the University Hospitals of Son Dureta and Son Espases in Palma, Balearic Islands, between January 1997 and December 2007 were selected for this study. From a total of 6196 cervical biopsies, 132 diagnosed cases of CIN2 were in a good state of conservation in a paraffin-embedded tissue block and were macroscopically assessable (over 2mm) (CASES).

As CONTROLS, 154 cervical archival biopsies diagnosed between 2015 and 2016 were selected from the hospital.

Biopsies that were too small and blocks from patients with no records or follow-ups in the hospital were excluded.

Therefore, this study analyses the following materials:

- •

286 biopsies:

- ∘

132 from archival biopsies of CIN2

- ∘

154 recently diagnosed biopsies:

- •

11 negative biopsies

- •

102 CIN1

- •

7 CIN2

- •

34 CIN3

Two technicians with specific pathology training (NL and AB) cut two slides from each of the 132 paraffin blocks from the CASES: one was stained with p16 and the other with haematoxylin–eosin (H&E). P16 was used for 52 randomly selected biopsies from the 154 CONTROL biopsies.

For p16 we used the CINtec® Histology Kit (Ventana Roche Diagnostics, Tucson, Arizona) which was used with staining systems Ventana BenchMarch ULTRA and detection kit OptiView DAB IHC.

Three assessing pathologists with over 20 years of experience took part in this study (GMC, JEST and JJTR). They are all General Pathologists, one of them specialized in Gynaecologic Pathology (GMC) and the other in Gynaecologic Cytopathology (JEST).

The pathologists performed three diagnostic rounds:

- 1.

First round: Assessment of H&E

Pathologists reassessed the 286 biopsies stained with H&E and established a diagnosis according to the CIN classification. Six diagnostic categories were established:

0: Negative biopsy

1: CIN 1

2: CIN 2

3: CIN 3

4: Carcinoma

5: Adenocarcinoma

6: Non-assessable biopsy

All three pathologists assessed in sequence the same sections and in the same order. None of them were aware of the previous diagnosis or of other pathologists’ diagnosis.

- 2.

Second round: Assessment of p16

All three pathologists were to separately assess the 132 biopsies previously stained with p16, without the corresponding H&E staining.

They were asked to classify biopsies in two levels of diagnosis, following Bergeron's14 recommendations:

- •

Positive: value 1, strong and diffuse staining throughout the full epithelial thickness.

- •

Negative: value 0, any other option:

- ∘

No staining.

- ∘

Focal, patchy or diffuse staining affecting only the basal layer of the epithelium.

- 3.

Third round: Assessment of H&E+p16

The assessing pathologists were provided with 132 biopsies (CASES) and 52 CONTROL biopsies randomly selected from the 154 biopsies for p16 staining; a total of 184 biopsies were reviewed with H&E+p16. Pathologists were provided with both H&E and the corresponding p16 stained lamellae.

The same diagnostic scale from the first round was used to establish a diagnosis, but this time using p16 staining.

After collecting data from all three rounds the following was analyzed:

- •

Inter-observer agreement

- ∘

When establishing a diagnosis with H&E only: Round 1.

- ∘

When establishing a diagnosis with p16: Round 2.

- ∘

When establishing a diagnosis with H&E+p16: Round 3.

- •

Intra-observer agreement when establishing a diagnosis with H&E only (round 1) versus H&E+p16 (round 3).

Results for continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation, and results for categorical variables use case-count and frequency for each category relative to the total. Value and 95% confidence interval are presented in certain estimators.

A sample size calculation was not formally performed since a large sample of women participants and their convenience samples was available.

The statistical significance shown in the tables is compared in each variable by performing first an ANOVA and then a bilateral test for continuous variables, and a Chi2 test for categorical variables. Pearson and Spearman's23 correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationship between continuous and discrete variables, respectively.

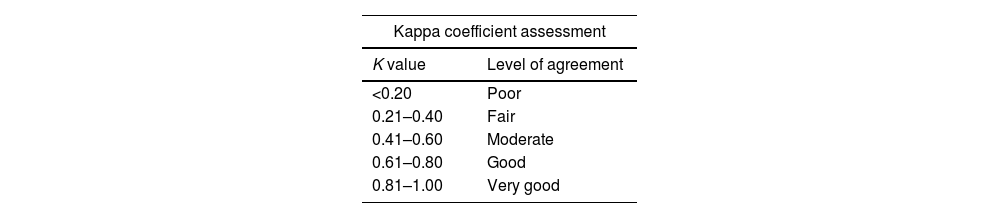

The percentage of concordant cases and kappa index were used to establish agreement between pathologists. This estimator includes pure chance agreements proportional to the observed agreements. When interpreting the kappa value, although arbitrary, it can be helpful to have a scale such as the following in Table 1.

Taken from23 statistical significance levels were less than 0.05 for all statistical tests performed.

| Kappa coefficient assessment | |

|---|---|

| K value | Level of agreement |

| <0.20 | Poor |

| 0.21–0.40 | Fair |

| 0.41–0.60 | Moderate |

| 0.61–0.80 | Good |

| 0.81–1.00 | Very good |

All three pathologists assessed all 286 H&E-stained biopsies. In the first round each pathologist's diagnosis was compared with our “GOLD STANDARD” (GS) – the sign out diagnosis for each of the 286 biopsies that determined the treatment patients received at the time. It also allowed a comparison of each pathologist with the same series.

The level of agreement for CIN2 and GS series diagnoses was 48.6% for pathologist 1 (P1), 71% for pathologist 2 (P2) and 48.6% for pathologist 3 (P3).

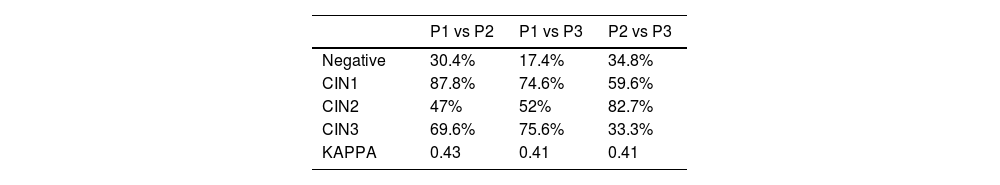

Pathologists’ diagnoses were also compared with each other. Agreement between P1 and P2 for the diagnosis of CIN2 was 47%, much lower than for CIN1 (87.8%) and also for CIN3 (69.6%), for which the total Kappa index (K) is 0.43.

The level of agreement between P1 and P3 for CIN2 was 52%, also much lower than for CIN1 (74.6%) and for CIN3 (75.6%), K index of 0.41.

Comparing P2 vs P3, level of agreement was 82.7% for CIN2, 59.6% for CIN1 and 33.3% for CIN3 with a K index of 0.41.

In the second round biopsies stained with p16 were assessed, without any H&E stains. A document with explanations on how to interpret the technique was provided. Two of the pathologists had no previous experience with this technique, leaving three diagnostic options:

0=negative

1=positive

6=Not assessable

Percentages of agreement between different pathologists were studied with the following results:

- •

Between P1 and P2 the agreement was 86.7% for the negative results and 95.9% for the positive results, with a K index of 0.82.

- •

Between P1 and P3 it was 60% for the negative results and 100% for the positive results, with a K index of 0.64.

- •

Between P2 and P3 it was 59.2% for the negative cases and 98.7% for the positive cases, with a K index of 0.62.

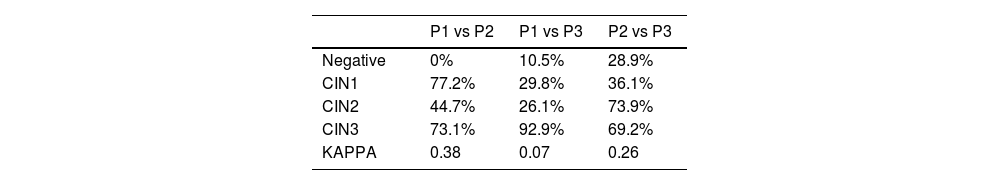

In the third round, they were provided with 184 biopsies with the corresponding H&E and p16. All three pathologists had to establish the diagnosis of the biopsies based on the same six categories from the first round.

The percentages of agreement between different pathologists for CIN2 were again studied with the following results:

- •

Between P1 and P2 the agreement was 44.7%, with a total K of 0.38.

- •

Between P1 and P3 it was 26.1% with a total K of 0.071.

- •

Between P2 and P3 it was 73.9% with a total K of 0.26.

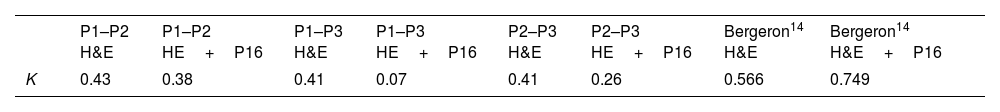

In this study we compared our results with those from the most important series in the literature. We first compared each pathologist's analytical results with the sign-out diagnoses of the biopsies (GOLD) and with the series from Galgano20 and Klaes.16Table 2 shows the results, including the total agreement Kappa index.

A detailed analysis of the results shows that pathologist 1 and pathologist 3 came close to what was expected in terms of agreement percentages. Agreement in the diagnosis of CIN2 is 48%, and between 70% and 80% in the diagnosis of CIN3. Galgano reports 47.6% for CIN2 and 75% for CIN3.

The data in Table 2 also show that all the pathologists report an index between 0.41 and 0.43, a moderate level of agreement.

These are good results when compared to data reported by Bergeron.13,14 In those studies agreement in K values ranges from 0.45 to 0.50, with previous series in which K did not exceed 0.2.11 However our results are not so good when compared to the 0.6 published by Klaes.16 The reason is that in those studies Kappa index is achieved by having expert pathologists analyze cone biopsies, whereas we had general pathologists analysing punch biopsies. The fact that biopsies were smaller may slant towards lower agreement. According to the literature, K index may range from 0.49 in punch biopsies to 0.63 in cone biopsies.24,25

Table 3 also illustrates quite well what was expected according to the literature, except agreement between pathologists 2 and 3 for CIN2 and CIN3. This might be because pathologist 2 has diagnosed a very high number of CIN2, at the expense of downgrading lesions that pathologist 3 considered CIN3. However, K index is still above 0.40, showing moderate agreement.

Besides considering reference from Bergeron, in a recent publication Liu25 classifies strong/diffuse staining as positive, focal/weak staining as negative and also describes a series of “ambiguous” or unclassifiable cases that do not fall into either of the two categories. 70% of ambiguous cases were found to be negative for high risk-HPV.

Table 4 shows how this study found variable p16 positivity percentages for each pathologist. The fourth column represents the percentage of positive results after establishing the consensus values.

Percentages of positivity between pathologists 1 and 2 are revealed to be very similar, but pathologist 3 presents a noticeably lower percentage.

On the other hand, Table 5 shows observer agreement when interpreting p16 and includes the coefficients reported by Meserve,10 Galgano20 and Bergeron.14

In the two comparisons involving pathologist 3, the Kappa index is worthy of notice – bearing in mind that pathologist 3 was the one diagnosing fewer positive results. This might be because the aforementioned articles and references lack consensus in the interpretation criteria for p16 stains. Bergeron13 suggests that pathologists receive a 30-min training session before the interpretation of p16. Each one of our three pathologists received an information brochure on how to interpret the staining, which could only be positive or negative, with no intermediate values. We also stressed the fact that only biopsies with strong and diffuse staining throughout the full epithelial thickness should be considered positive.

The challenges to interpret positivity or to meet the requirements to report as positive may explain these differences. For some authors a 5% strong and diffuse cell staining is enough to be positive, whereas others require at least 50% or more. This clearly shows the subjective matter of interpreting a positive or a negative p16 stain. It is indeed not a simple and objective technique; to date we still lack guidelines or consensus values.

Study of biopsies stained with H&E and p16A total of 184 biopsies were reviewed in the third round. This number includes 132 biopsies from the CASES and shuffled with 52 randomly selected biopsies from the CONTROL group.

Agreement percentages in Table 6 are revealed to be very variable and well below those reported in the literature. Also Kappa values are very low, much lower than expected and lower than the results from H&E only.

Table 7 shows a summary of K values from each series compared to the literature.

When comparing results from each pair of pathologists, it is observed that, when p16 was available to pathologists, agreement was lower in all cases, contrary to what is reported.16

Intra-observer agreement after p16 was also analyzed; i.e. we compared the diagnosis from each pathologist first with H&E only and then with the p16 interpretation. The following Kappa values are obtained after analysing the three values.

- •

Pathologist 1: 0.456

- •

Pathologist 2: 0.592

- •

Pathologist 3: 0.323

Internal agreement between pathologists 1 and 2 is acceptable, but pathologist 3 with a lower positivity index has an intra-observer Kappa value of 0.323, considered weak.

What is the reason for such discrepancies and why are our results so different to the literature? One of the reasons might be that p16 was confusing, namely for pathologist 3, most likely because in this study we performed p16 and requested its reading for all biopsies regardless of the baseline diagnosis, which is not a recommended procedure. The LAST8 project only recommends using p16 for the following cases:

- •

Doubt between negative and CIN2 or 3

- •

CIN2 diagnosis

- •

Disagreement between pathologists

- •

Discouraged routine use for negative, CIN1 or CIN3.

These recommendations have been reinforced in subsequent series.19

Besides, in our study pathologists 2 and 3 had no previous experience with p16 staining, none of the three received training prior to interpreting the slides and as mentioned they were only provided with written information on which stain patterns should be considered positive or negative.

ConclusionsFor the present study three pathologists cooperated for consecutive readings of blinded specimens in different conditions. An almost systematic disagreement between one observer and the other two mimics everyday clinical practice: individual criteria have decisive influence over objective criteria in the pathologic diagnosis of some complex patterns.

In this context, p16 staining has been shown to improve agreement between pathologists with a previous higher agreement rate, but did not correct disagreement of the third observer with classical H&E staining. This finding was foreseeable, as the third observing pathologist also revealed discrepancies in the reading limited to p16-stained samples, despite strict reading criteria. The additional information provided did therefore not compensate for the subjective reading in uncertain situations.

Therefore,

- •

P16 protein may be useful as an addition to histologic diagnosis with H&E in equivocal cases when pathologists lack elements to establish a diagnosis of high or low grade cervical intraepithelial lesion.

P16 supplementary staining should be limited to selected cases and only after specialized training. There is a need to establish agreed p16 interpretation standards.

Ethical considerationsIt is an original research study, performed at the University Hospital Son Espases of Palma, with the agreement of the Research Committee of the hospital and the approval of the Balearic Islands ethics committee (file number IB 3196/16 PI) performed following the PhD programme of Barcelona Autonomous University.

Approval by the Balearic Islands Ethics CommitteeIB 3190/19 PI.

Informed consentAs the samples have been collected and analyzed during the daily practice and it is a retrospective study, with cases collected from our files, and since the only intervention to the patients is the review of their medical records, we think it may be not necessary to obtain their informed consent. The information will be only used for statistical analysis. This information was sent to the ethics committee for approval.

FundingFor performing this study, I have received two immunohistochemistry kits from Roche and a grant from Mutual Medica for carrying out doctoral dissertations.

Conflict of interestAF has received funding for research and for attendance at Roche Diagnostics conferences. JC has received travel and/or research funding and/or honoraria for conferences and/or consultancies from Genomics, GSK, Merck, Procare Health, Qiagen, Roche and SPMSD. CV and GM declare no conflict of interest for this article. CV declares no conflict of interest. GM declares no conflict of interest.