Genetic polymorphism in the BDNF gene has been found to cause neuronal alterations and has been identified as a causal factor for many neuropsychiatric disorders. Therefore, various neurological case–control studies and meta-analyses have been conducted to find the possible link between BDNF and susceptibility to schizophrenia.

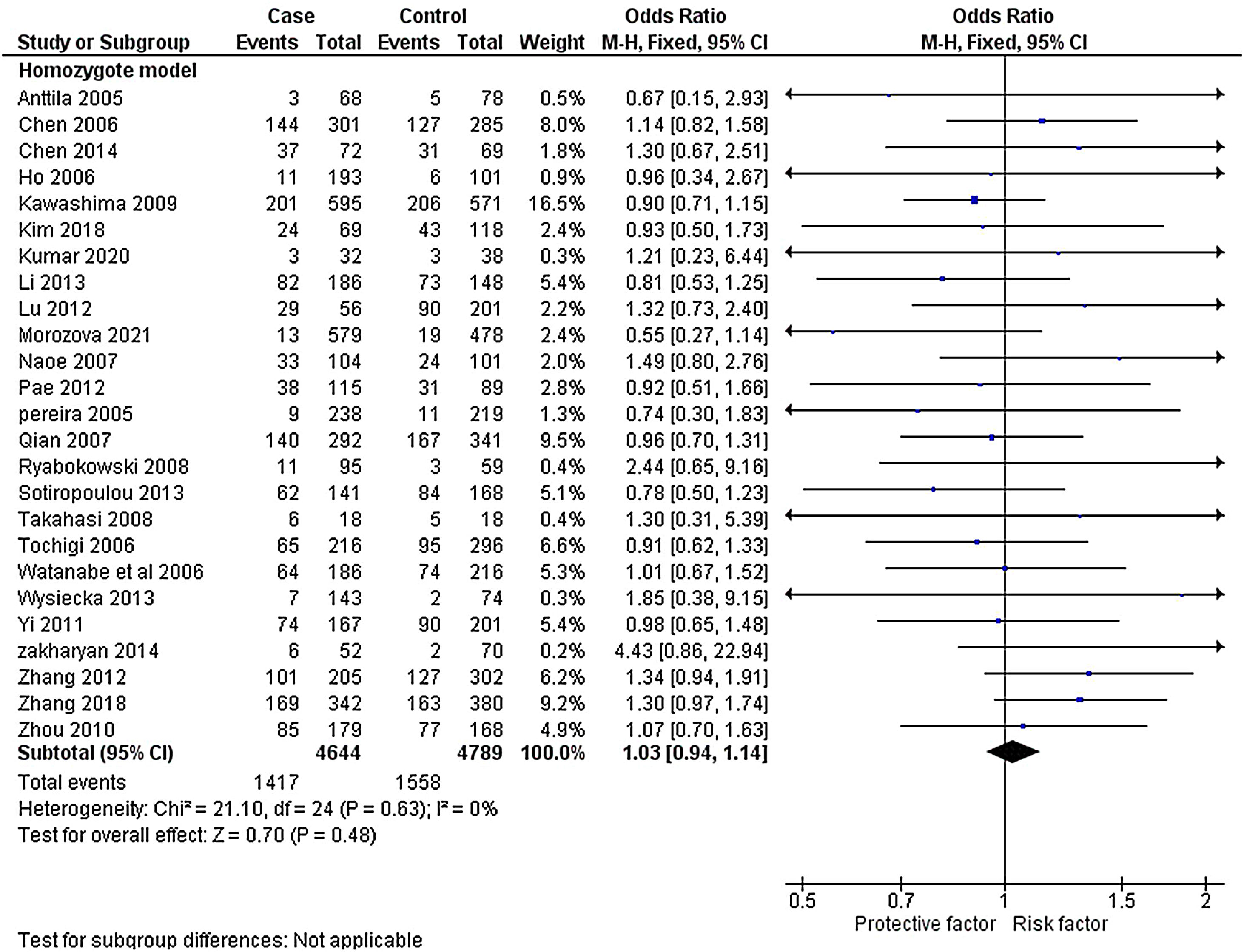

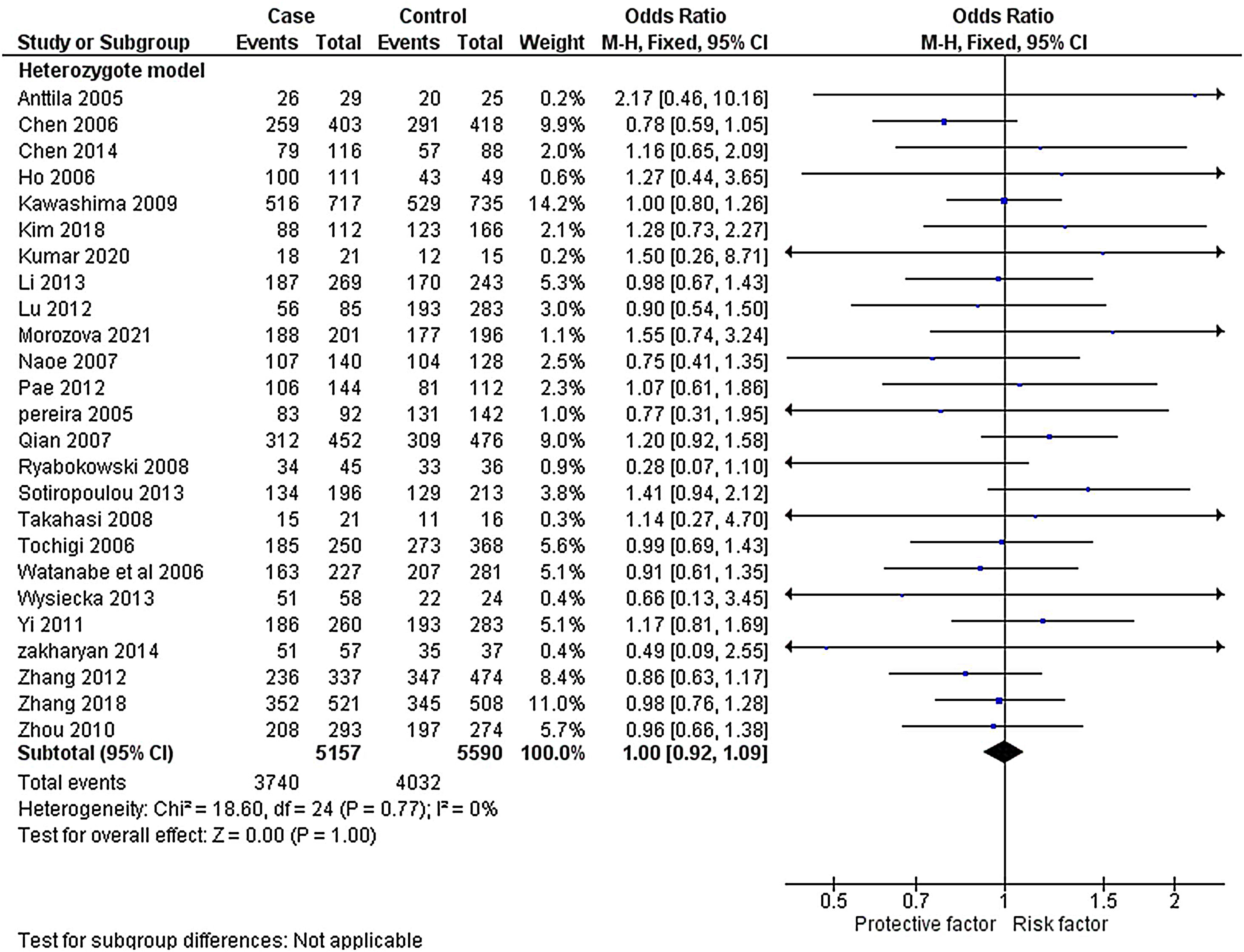

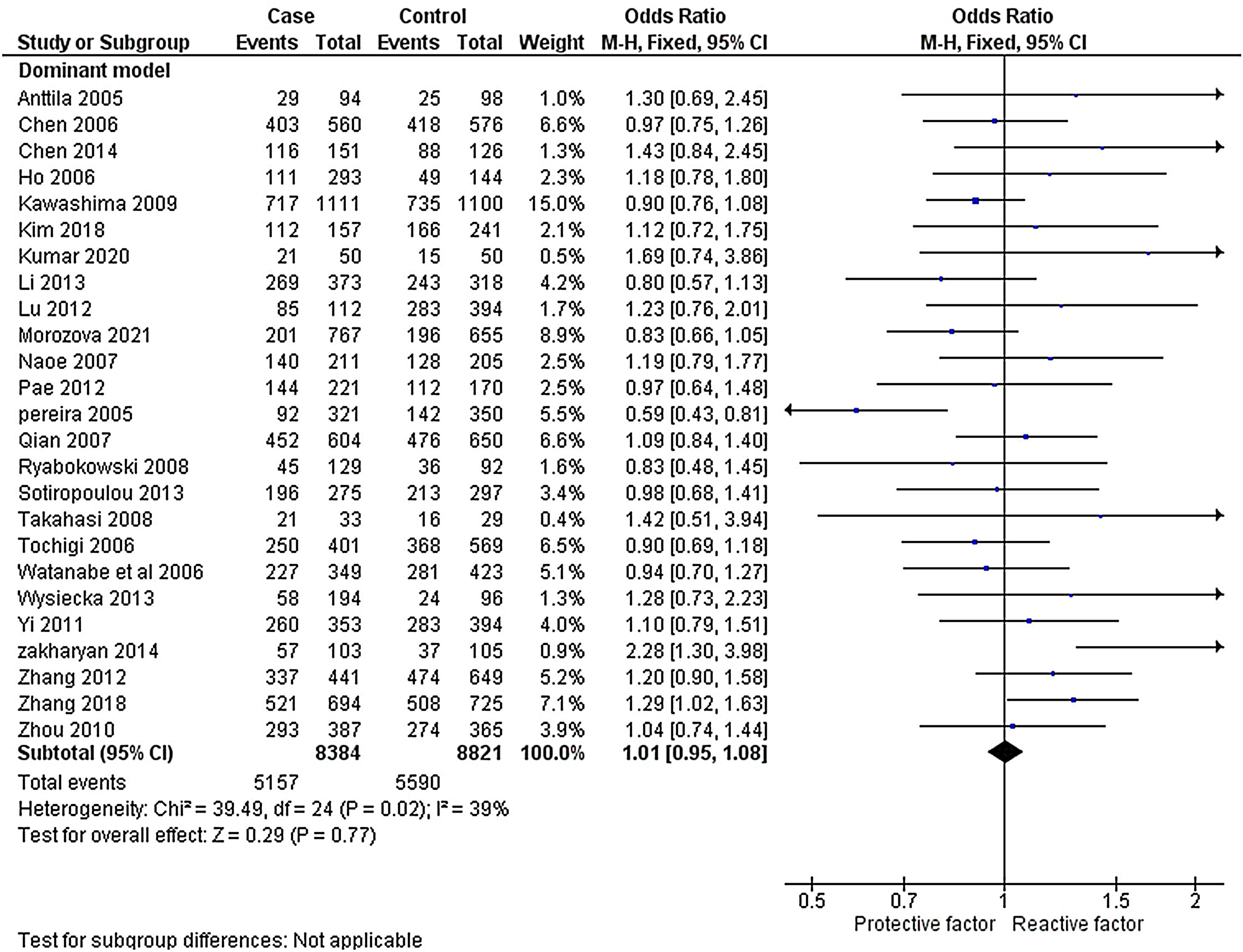

MethodThis meta-analysis gathered data from 25 case–control studies including a total of 8384 patients with schizophrenia and 8821 controls in order to identify the relationship between the rs6265 single nucleotide polymorphism and the disease, evaluating the combined odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals under 5 different genetic models. Validation followed the “Leave one out” method, and we used the Egger test and Begg's funnel plot to identify publication bias.

ResultsResearch into the rs6265 (G/A) polymorphism revealed a non-significant association with schizophrenia in all 5 genetic models; in the subgroup analysis, no association was found between white and Asian populations, with a p value>.05.

ConclusionsOverall, the updated meta-analysis revealed that rs6265 exonic polymorphisms do not increase susceptibility to this disease. However, to better understand the pathogenesis of the disease, there is a need for further case–control studies into the BDNF polymorphism including larger sample sizes and different ethnic groups.

Se sabe que los polimorfismos del gen BDNF provocan alteraciones neuronales y parecen ser un factor causal en muchos trastornos neuropsiquiátricos. Es por ello que se han llevado a cabo varios metaanálisis y estudios de casos y controles con el objetivo de evaluar la posible relación entre BDNF y la esquizofrenia.

MétodoRealizamos un metaanálisis de 25 estudios de casos y controles, que incluyó un total de 8.384 pacientes con esquizofrenia y 8.821 controles. Se analizó la relación entre el polimorfismo de nucleótido simple rs6265 y la esquizofrenia mediante odds ratios combinados y sus intervalos de confianza del 95% con 5 modelos genéticos diferentes. Utilizamos el método de validación cruzada dejando uno fuera («leave one out»), la prueba de Egger y el gráfico en embudo de Begg para identificar posibles sesgos de publicación.

ResultadosLos estudios sobre el polimorfismo rs6265 (G/A) muestran una asociación no significativa con la esquizofrenia en los 5 modelos genéticos. En el análisis por subgrupos, no se encontró relación con las poblaciones caucásica y asiática (p>0,05).

ConclusionesLa presencia de polimorfismos rs6265 no aumenta la predisposición a desarrollar esquizofrenia. Sin embargo, se deben realizar más estudios de casos y controles sobre polimorfismos de BDNF, con muestras más numerosas y con individuos de diferentes grupos étnicos, para comprender mejor los mecanismos patogénicos de la enfermedad.

Schizophrenia (SCZ) affects 1% of the world's total population, and it is one of the essential neurologic disorders.1 The etiopathogenesis of this disease is quite complex and involves the interaction between several genetic and environmental factors.2,3 Genetic associations and neuropathological studies indicate that the modifications in synapse density cause these variations in the organization of the macroscale connectome in this psychiatric disease.4–7 Younger adults with this psychiatric condition are prone to age-related diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The age of onset of this disease from early childhood (6 years) to the youngest adults (20 years old), and earlier studies have shown that the mean age of 19 years has an ultra-high risk of this disease.8 Young SCZ adults are susceptible to aging-related conditions like diabetes mellitus (DM) and cardiovascular diseases (CVD).9–12 The average life expectancy of the individual with this disease condition is between 15 and 20 years lesser than that of the healthy individual,13,14 and the patients have 2–12 times the overall age-related mortality rate than the general population.15–17 GWAS on the genetic association of SCZ has recently been published, and it has been reported that the genes DRD2, GRM3, GRIN2A, SRR, GRIA1, BDNF, NRG1, COMT, and AKT1 are associated with the pathogenesis of this disease.18 Among these genes, BDNF is the most acceptable studied gene to find the relationship and pathogenesis of this disease,19 and this gene expansion is a brain-derived neurotrophic factor that belongs to the group of neurotrophins on chromosome 11 (11p14.1).20 It is responsible for various brain development processes such as neuronal development, neurite growth, and neuron survival.21 Many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been studied to identify the link to schizophrenia.22–24 A main functional genetic variation was discovered at the molecular level of this gene at codon 66, which leads to the substitution of valine (Val) and methionine (Met). The alteration in neurons and BDNF secretion affects the hippocampal brain function due to this polymorphism.25 rs6265 is also known as Val66Met or G196A. It has been extensively studied in relationship with schizophrenia among Asian, Caucasian, and Mixed populations.26–28 Many research projects can show results of type I (false positive) and therefore cannot recognize type II (false negative), which makes it challenging to make medical decisions when the data published contain conflicts or tiny sample sizes, which are shown by meta-analysis.29 We have investigated the relationship between the rs6265 polymorphism and susceptibility to SCZ based on the PRISMA guidelines.30

Subjects, materials, and methodsData sourcesOnline databases (Google Scholar, Medline, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Embase) were reviewed checked from January 2005 to May 2021 for all case–control studies assessing any genetic variants and schizophrenia in humans. Abstract, letters, and other than English language articles were omitted in this study. The Medical terms and keywords used for the search were schizophrenia or SCZ or BDNF or rs6265 gene polymorphism or Psychosis susceptibility syndrome or mutation or genes or genotype.

Study selectionThe research articles were examined on the source of our selection criteria for further procedures. The study includes a case–control design for assessing risk links between BDNF polymorphism and SCZ, articles including sample size, allelic and genotypic frequencies were freely accessible, schizophrenic patients diagnosed on the DSM-IV criteria. Therefore, the research performed by cell lines, animal models, state of the art, case report, insufficient genotypic information were excluded.

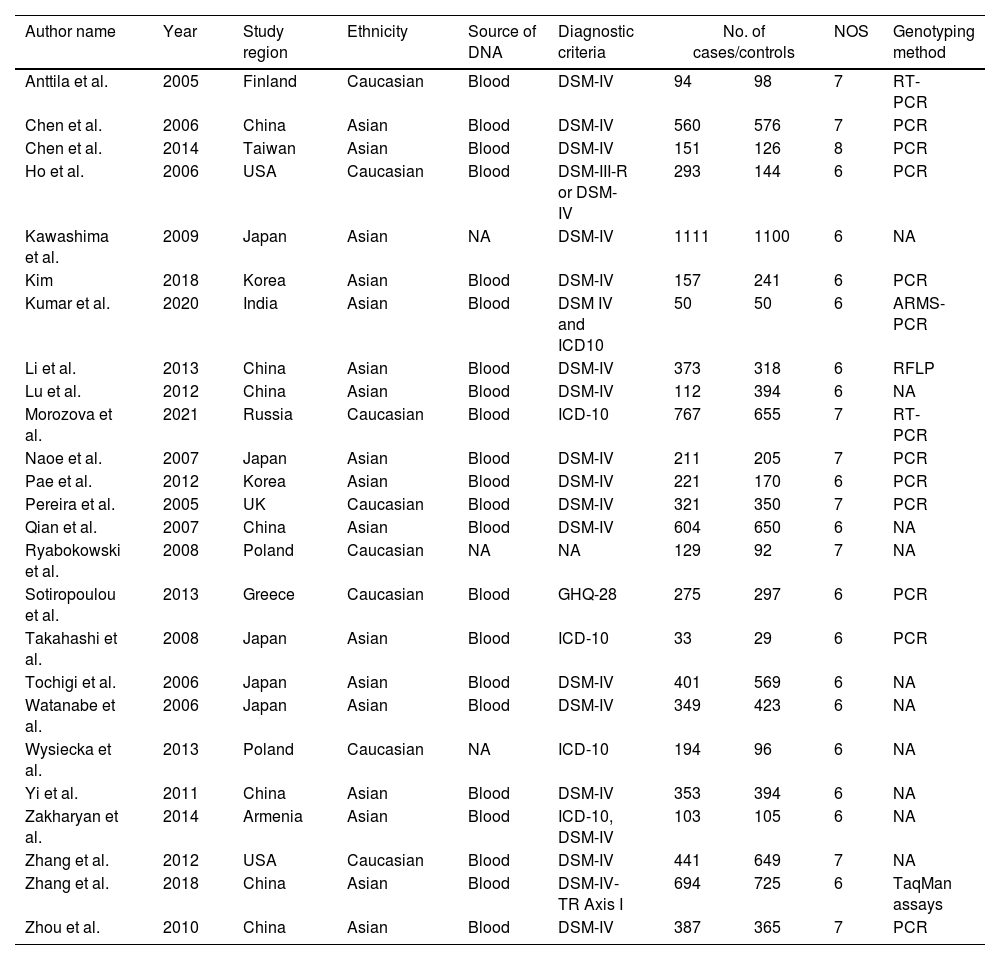

Data extractionTwo authors (VM and RV) individually obtained the data and variations fixed by a group conversation. The obtained information: author name, year of publication, country of study, population background, source of DNA, sample size (cases/controls), Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE), NOS score, and genotyping approaches were mined from certain studies (Table 1). Based on the HWE with p-value (<0.05) and NOS, the value of those studies was evaluated. The selection of the study, comparability between the parameters of the study, and study exposure are the three critical features of NOS with a rating of six or more were examined for this study.

The characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis.

| Author name | Year | Study region | Ethnicity | Source of DNA | Diagnostic criteria | No. of cases/controls | NOS | Genotyping method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anttila et al. | 2005 | Finland | Caucasian | Blood | DSM-IV | 94 | 98 | 7 | RT-PCR |

| Chen et al. | 2006 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 560 | 576 | 7 | PCR |

| Chen et al. | 2014 | Taiwan | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 151 | 126 | 8 | PCR |

| Ho et al. | 2006 | USA | Caucasian | Blood | DSM-III-R or DSM-IV | 293 | 144 | 6 | PCR |

| Kawashima et al. | 2009 | Japan | Asian | NA | DSM-IV | 1111 | 1100 | 6 | NA |

| Kim | 2018 | Korea | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 157 | 241 | 6 | PCR |

| Kumar et al. | 2020 | India | Asian | Blood | DSM IV and ICD10 | 50 | 50 | 6 | ARMS-PCR |

| Li et al. | 2013 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 373 | 318 | 6 | RFLP |

| Lu et al. | 2012 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 112 | 394 | 6 | NA |

| Morozova et al. | 2021 | Russia | Caucasian | Blood | ICD-10 | 767 | 655 | 7 | RT-PCR |

| Naoe et al. | 2007 | Japan | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 211 | 205 | 7 | PCR |

| Pae et al. | 2012 | Korea | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 221 | 170 | 6 | PCR |

| Pereira et al. | 2005 | UK | Caucasian | Blood | DSM-IV | 321 | 350 | 7 | PCR |

| Qian et al. | 2007 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 604 | 650 | 6 | NA |

| Ryabokowski et al. | 2008 | Poland | Caucasian | NA | NA | 129 | 92 | 7 | NA |

| Sotiropoulou et al. | 2013 | Greece | Caucasian | Blood | GHQ-28 | 275 | 297 | 6 | PCR |

| Takahashi et al. | 2008 | Japan | Asian | Blood | ICD-10 | 33 | 29 | 6 | PCR |

| Tochigi et al. | 2006 | Japan | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 401 | 569 | 6 | NA |

| Watanabe et al. | 2006 | Japan | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 349 | 423 | 6 | NA |

| Wysiecka et al. | 2013 | Poland | Caucasian | NA | ICD-10 | 194 | 96 | 6 | NA |

| Yi et al. | 2011 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 353 | 394 | 6 | NA |

| Zakharyan et al. | 2014 | Armenia | Asian | Blood | ICD-10, DSM-IV | 103 | 105 | 6 | NA |

| Zhang et al. | 2012 | USA | Caucasian | Blood | DSM-IV | 441 | 649 | 7 | NA |

| Zhang et al. | 2018 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV-TR Axis I | 694 | 725 | 6 | TaqMan assays |

| Zhou et al. | 2010 | China | Asian | Blood | DSM-IV | 387 | 365 | 7 | PCR |

NA; not available, PCR; polymerase chain reaction, RT; real-time; NOS; Newcastle Ottawa Scale; RFLP; Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism, DSM-IV; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV, ICD-10; International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision, GHQ-28; General Health Questionnaire-28.

BDNF genes were selected to identify the significant association with SCZ. The author has selected the SNP rs6265 based on the number of studies available in the electronic database. The risk association was considered by odds ratios (ORs) with a 95% confidence interval (CIs) with p-value (<0.05) under allelic (G vs. A) (G-major, A-minor allele), homozygote (GG vs. AA), heterozygote (GA vs. AA), dominant (GG+GA vs. AA) and recessive (GG vs. GA+AA) genetic models. Q-statistic tests and I2 values were considered to identify the heterogeneity of the selected SNP.31 Based on the I2 value, random-effects (DerSimonian and Laird's) and fixed-effects (Mantel-Haenszel) were implemented.32 The Begg's funnel plot and Egger's linear test were done to avoid publication bias.33 The leave one out method was used to confirm the adaptability of this meta-analysis for the sensitivity test: the Rev-Man 5.4 software generated all the statistical meta-analyses, forest plots, and funnel plots.

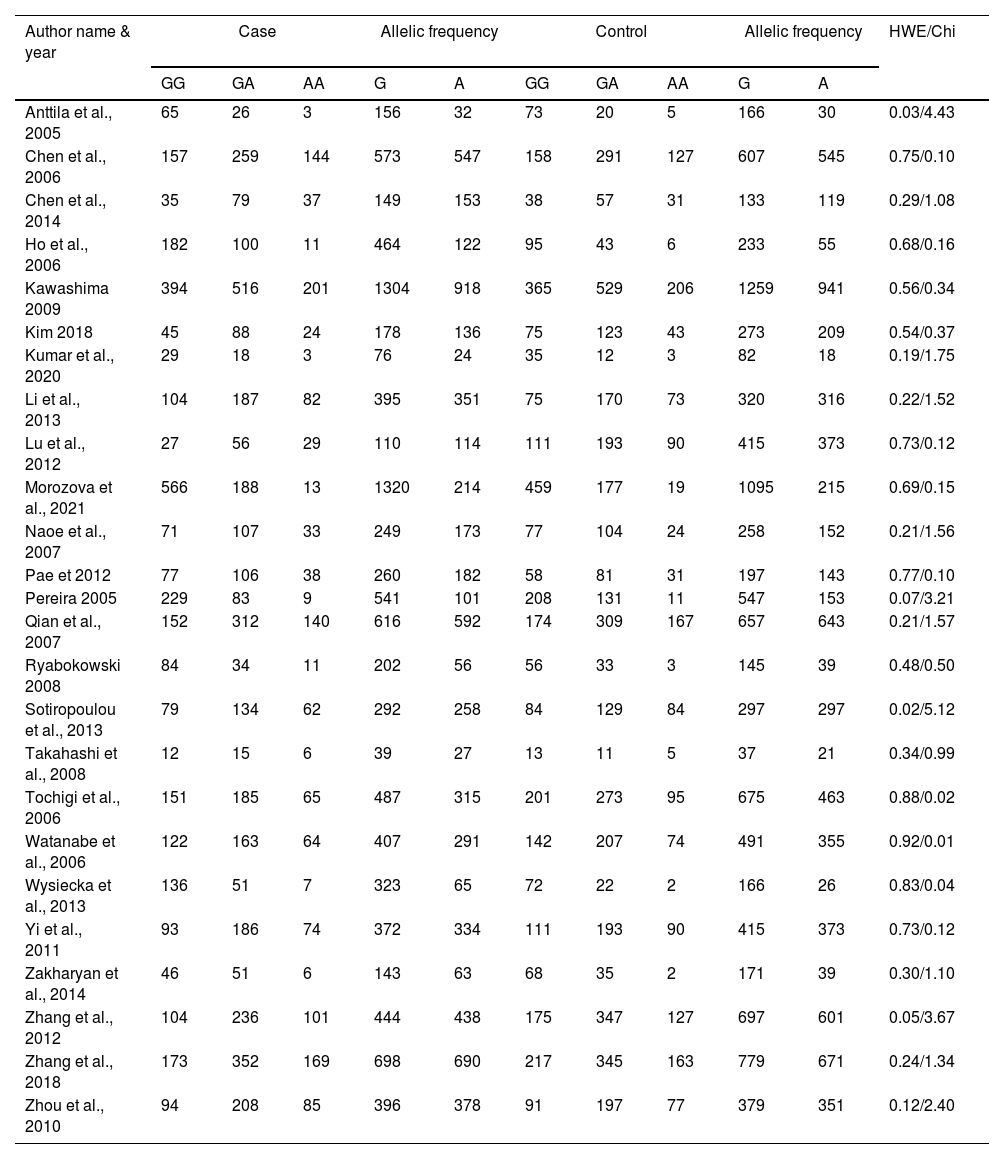

ResultsLiterature extraction835 potentially relevant studies were identified through different databases related to genetic polymorphism in schizophrenia. 650 studies based on abstracts or full study articles were skipped due to irrelevant genetic information. There are 108 possibly eligible articles selected that are related to the objective of this research. The study flow diagram shows that only 2526–28,34–55 articles were considered based on the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). All selected studies were evaluated using HWE and NOS. The information obtained from the selected studies is mentioned in Table 2.

Genotypic and allelic frequency of rs6265 polymorphism.

| Author name & year | Case | Allelic frequency | Control | Allelic frequency | HWE/Chi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | GA | AA | G | A | GG | GA | AA | G | A | ||

| Anttila et al., 2005 | 65 | 26 | 3 | 156 | 32 | 73 | 20 | 5 | 166 | 30 | 0.03/4.43 |

| Chen et al., 2006 | 157 | 259 | 144 | 573 | 547 | 158 | 291 | 127 | 607 | 545 | 0.75/0.10 |

| Chen et al., 2014 | 35 | 79 | 37 | 149 | 153 | 38 | 57 | 31 | 133 | 119 | 0.29/1.08 |

| Ho et al., 2006 | 182 | 100 | 11 | 464 | 122 | 95 | 43 | 6 | 233 | 55 | 0.68/0.16 |

| Kawashima 2009 | 394 | 516 | 201 | 1304 | 918 | 365 | 529 | 206 | 1259 | 941 | 0.56/0.34 |

| Kim 2018 | 45 | 88 | 24 | 178 | 136 | 75 | 123 | 43 | 273 | 209 | 0.54/0.37 |

| Kumar et al., 2020 | 29 | 18 | 3 | 76 | 24 | 35 | 12 | 3 | 82 | 18 | 0.19/1.75 |

| Li et al., 2013 | 104 | 187 | 82 | 395 | 351 | 75 | 170 | 73 | 320 | 316 | 0.22/1.52 |

| Lu et al., 2012 | 27 | 56 | 29 | 110 | 114 | 111 | 193 | 90 | 415 | 373 | 0.73/0.12 |

| Morozova et al., 2021 | 566 | 188 | 13 | 1320 | 214 | 459 | 177 | 19 | 1095 | 215 | 0.69/0.15 |

| Naoe et al., 2007 | 71 | 107 | 33 | 249 | 173 | 77 | 104 | 24 | 258 | 152 | 0.21/1.56 |

| Pae et 2012 | 77 | 106 | 38 | 260 | 182 | 58 | 81 | 31 | 197 | 143 | 0.77/0.10 |

| Pereira 2005 | 229 | 83 | 9 | 541 | 101 | 208 | 131 | 11 | 547 | 153 | 0.07/3.21 |

| Qian et al., 2007 | 152 | 312 | 140 | 616 | 592 | 174 | 309 | 167 | 657 | 643 | 0.21/1.57 |

| Ryabokowski 2008 | 84 | 34 | 11 | 202 | 56 | 56 | 33 | 3 | 145 | 39 | 0.48/0.50 |

| Sotiropoulou et al., 2013 | 79 | 134 | 62 | 292 | 258 | 84 | 129 | 84 | 297 | 297 | 0.02/5.12 |

| Takahashi et al., 2008 | 12 | 15 | 6 | 39 | 27 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 37 | 21 | 0.34/0.99 |

| Tochigi et al., 2006 | 151 | 185 | 65 | 487 | 315 | 201 | 273 | 95 | 675 | 463 | 0.88/0.02 |

| Watanabe et al., 2006 | 122 | 163 | 64 | 407 | 291 | 142 | 207 | 74 | 491 | 355 | 0.92/0.01 |

| Wysiecka et al., 2013 | 136 | 51 | 7 | 323 | 65 | 72 | 22 | 2 | 166 | 26 | 0.83/0.04 |

| Yi et al., 2011 | 93 | 186 | 74 | 372 | 334 | 111 | 193 | 90 | 415 | 373 | 0.73/0.12 |

| Zakharyan et al., 2014 | 46 | 51 | 6 | 143 | 63 | 68 | 35 | 2 | 171 | 39 | 0.30/1.10 |

| Zhang et al., 2012 | 104 | 236 | 101 | 444 | 438 | 175 | 347 | 127 | 697 | 601 | 0.05/3.67 |

| Zhang et al., 2018 | 173 | 352 | 169 | 698 | 690 | 217 | 345 | 163 | 779 | 671 | 0.24/1.34 |

| Zhou et al., 2010 | 94 | 208 | 85 | 396 | 378 | 91 | 197 | 77 | 379 | 351 | 0.12/2.40 |

HWE; Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium.

The heterogeneity was carried out in this SNP and found the no significance in homozygous, heterozygous and recessive (I2=0%) and moderate I2 in allelic model (I2=33%) and dominant model (I2=39%) was adopted fixed effect model. The p-value (>0.05) exposed irrelevant relationship with SCZ risk in allelic, homozygote, heterozygote, dominant and recessive model shows (OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.96–1.05, z=0.34, p=0.73: OR=1.03, 95% CI=0.94–1.14, Z=0.70, p=0.48; OR=1.00, 95% CI=0.92–1.09, z=0, p=1.00; OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.95–1.08, z=0.29, p=0.77; OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.93–1.10, z=0.26, p=0.80). The Meta-analysis data was generated as a forest plot shown in Figs. 2–6. In the investigated models, the Egger's test and Begg's funnel plot (Supplementary file 1) were performed to identify the publication bias.

To analyze the association between the ethnicity and rs6265 polymorphism in SCZ, the authors have done the subgroup analysis by separating the selected studies as Caucasian, Asian and mixed. From a total of 25 studies, it was found that 17 are Asian and 8 have Caucasian ethnic origins. The subgroup analysis of the Asian population revealed no heterogeneity in all the investigated genotypic models {allelic (I2=10%); homozygous, heterozygous, recessive (I2=0%); dominant (I2=25%)}. Hence, the fixed effect was implemented for all the genetic models which showed no relationship in the SCZ with allelic, homozygote, heterozygote, dominant and recessive model shows (OR=1.02, 95% CI=0.97–1.08, z=0.89, p=0.37; OR=1.04, 95% CI=0.94–1.15, z=0.73, p=0.47; OR=1.00, 95% CI=0.91–1.09, z=0.10, p=0.92; OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.99–1.04, z=1.05, p=0.30; OR=1.02, 95% CI=0.93–1.11, z=0.36, p=0.72).

Likewise, the subgroup analysis of SNP in rs6265 in Caucasian population revealed no heterogeneity in homozygous (I2=25%) and recessive (I2=29%), moderate heterogeneity in heterozygous (I2=30%), substantial heterogeneity in allelic (I2=55%), and dominant (I2=55%). Depend on the I2 value, the random and fixed effect was applied which revealed insignificant association in the SCZ with allelic, homozygote, heterozygote, dominant and recessive model shows (OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.82–1.13, z=0.55, p=0.58, OR=1.01, 95% CI=0.80–1.27, z=0.09, p=0.93; OR=1.02, 95% CI=0.83–1.27, z=0.22, p=0.83; OR=0.96, 95% CI=0.78–1.17, z=0.41, p=0.68; OR=0.98, 95% CI=0.80–1.20, z=0.18, p=0.86). The meta-data subgroup analyses were represented as forest plots and Begg's funnel plots (Supplementary file 2).

Sensitivity analysisThe sensitivity test was implemented using the leave-one-out procedure to analyze the influence on pooled ORs of each research. There were no changes in pooled ORs that consistently confirmed our results. In addition, Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test were used to identifying the study's publication bias and conclude that there is no publication bias for the investigated polymorphism in any of the genetic models.

DiscussionSchizophrenia is a complex inheritance disease that weakens neurons in the brain, and the symptoms of this neuropsychiatric disorder are delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, and lack of motivation.56 The successful investigation of many genes in the last few decades has provided valuable insights into the molecular epidemiology of this disease.57 Numerous studies on genetic polymorphism found the>100 schizophrenia-linked loci and revealed that it is a multiple genetic disorder (polygenic) defined by distinct genetic variations but with a small effect size.58,59 Studies of the association of candidate genes have revealed specific genes that could be assumed to contribute to this psychiatric condition in both functional and positional, such as neuregulin 1 (NRG1),60 brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF),61 catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)62 and protein kinase 1 (AKT1).63 The most extensively studied SNP is rs6265 in the BDNF gene, which shows the possible association with this disease.19 Therefore, a BDNF meta-analysis of the rs6265 polymorphism was achieved, which can help assess the polymorphism's effect in a larger sample. In addition, through the genotyping testing, it might be helpful to diagnose this disease in the earlier stage. This meta-analysis did the subgroup investigation of Asian and Caucasian ethnic backgrounds that contradict the findings of existing case–control researches.

The meta-analysis of BDNF rs6265 genetic alteration showed an inconsistent relationship with all the genetic models with a p-value>0.05. The subgroup analysis also revealed no association between the selected SNP (rs6265) with schizophrenia in Caucasian and Asian populations. Three studies34,47,52 investigated the rs6265 polymorphism had insignificant sample sizes, representing probable population classification. The cross-validation was done by the leave one out method, Egger's test, and generating Begg's funnel plot to identify the publication bias. In agreement with our results, earlier meta-analyses have also recommended that BDNF rs6265 polymorphism is not associated with SCZ.19,38,63

In contrast,64 study showed a significant association with the heterozygous model (Met/Met carriers) with schizophrenia, and23 revealed a significant association between Met/Met carriers with Asian, Caucasian, and mixed SCZ populations. However, this study consists of 8384 patients with schizophrenia and 8821 controls (no sign of any psychiatric disorder) for the current meta-analysis. Compared to earlier meta-studies, the sample size is small, but the authors have included the most recently published case–control studies and compared for the same (Kumar et al., 2020, Morozova et al., 2021). The main limitation of this meta-study is that we did not identify the possible relationship between the rs6265 polymorphism and the heterogeneity of subclinical schizophrenic conditions.

ConclusionIn this meta-analysis, the SNP rs6265 in BDNF exposed the irrelevant association with this disease, and the gene is not susceptible to schizophrenia. The collected literature studies might indicate that the role of BDNF in several neuropsychiatric disorders, but it is not a functional gene in this disease. More research has been done in the same parameters in the past few decades, but only a few studies have shown the associated results. Therefore, BDNF could be a perfect target for this psychiatric condition to diagnose the disease pathogenesis. However, as expected, the results were not obtained in the previous case–control studies due to the lack of research design, inadequate sample size, and ethnic selection. So, in the future, to understand the pathogenesis of this disease through this gene, the researcher should choose a proper ethnic background with larger sample size.

Author's contributionsVM extracted the literature from the database, assessed the allelic and genotypic frequency, done the statistical analysis, and generated the plots.

RV design, revise and corrected the manuscript.

Availability of data and materialNot applicable.

Code availabilityNot applicable.

Ethics approvalNot applicable.

Consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationAll authors approved the manuscript for publication.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest to report.

The authors thank the Chettinad Academy of Research Education (CARE) for the constant support and encouragement.