To assess adherence to and the adverse effects of the SARS-COV vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Patients and methodsThis is an observational, analytical, cross-sectional study. Sociodemographic and clinical data, SARS-COV vaccine data, medications for IBD with use during the vaccination period, and adverse events during the vaccination period were collected. Carried out logistic regressions with robust variance estimation to estimate the odds ratio with the respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) to assess the factors associated with non-serious adverse effects following vaccine doses as outcome variables.

Results194 patients participated, with vaccine compliance of 78.3% for three doses of any vaccine (n=152). Local symptoms and mild systemic symptoms predominated, regardless of the type of vaccine. The first dose of the SARS-COV vaccine with AstraZeneca had a higher percentage of patients with vaccine symptoms. AstraZeneca vaccine increased the chance of non-serious adverse effects in IBD patients by 2.65 times (95% CI: 1.38–5.08; p=0.003), regardless of age, gender, physical activity, excess weight, use of disease-modifying drugs, immunobiological and corticosteroids. CoronaVac vaccine was associated with asymptomatic patients at the first dose and reduced the chance of adverse effects by 0.28 times (OR: 0.284; 95%CI: 0.13–0.62; p=0.002).

ConclusionLocal symptoms and mild systemic symptoms predominated, regardless of the type of vaccine. Using CoronaVac in the first dose reduced the chances of adverse effects, while AstraZeneca increased the risk of adverse effects.

Evaluar la adherencia y los efectos adversos de la vacuna SARS-CoV-2 en los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII).

Pacientes y métodosSe trata de un estudio observacional, analítico y transversal. Se recogieron los datos sociodemográficos y clínicos; los datos de la vacuna SARS-CoV-2, los medicamentos para la EII con el uso durante el período de vacunación y los efectos adversos tras la vacunación. Se realizaron regresiones logísticas con estimación robusta de la varianza para estimar la odds ratio con los respectivos intervalos de confianza del 95% (IC 95%) para evaluar los factores asociados a los efectos adversos no graves tras las dosis de vacuna como variables de resultado.

ResultadosParticiparon 194 pacientes, con adherencia vacunal del 78,4% para 3 dosis de cualquier vacuna (n=152). Predominaron los síntomas locales y los síntomas sistémicos leves, independientemente del tipo de vacuna. La primera dosis de la vacuna SARS-CoV-2 con AstraZeneca tuvo un mayor porcentaje de pacientes con síntomas vacunales. La vacuna AstraZeneca aumentó 2,65 veces (IC 95%: 1,38-5,08; p=0,003) la probabilidad de efectos adversos no graves en pacientes con EII, independientemente de la edad, el sexo, la actividad física, el exceso de peso, el uso de fármacos modificadores de la enfermedad, inmunobiológicos y corticosteroides. La vacuna CoronaVac® se asoció a pacientes asintomáticos en la primera dosis y redujo la probabilidad de efectos adversos 0,28 veces (OR: 0,284; IC 95%: 0,13-0,62; p=0,002).

ConclusiónSe observó un predominio de los síntomas locales y los síntomas sistémicos leves, independientemente del tipo de vacuna. El uso de CoronaVac® en la primera dosis redujo las posibilidades de efectos adversos, mientras que AstraZeneca aumentó el riesgo de efectos adversos.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are pathologies characterized by a chronic inflammatory process, mostly represented by two entities: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD).1 The drugs used in treatment can cause immunosuppression in these patients, making them more susceptible to vaccine-preventable infections. For this reason, it has been recommended updating the vaccination schedule before starting immunosuppressive therapy.2

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-COV-2 vaccines were developed and made available for use in the general population.3 COVID-19 vaccines have been developed using different technologies, some with inactive viruses, vaccines with attenuated viruses, viral vector vaccines (AstraZeneca and Janssen) and mRNA-based vaccines (Pfizer and BioNTech, BNT162b2).4 In Brazil, inactive virus (CoronaVac/Sinovac), recombinant (AstraZeneca/Fiocruz and Janssen), and mRNA (Pfizer/Wyeth) vaccines have been approved and distributed by the Unified Health System.5 Regarding vaccination schedules, the Brazilian guidelines recommend eight weeks between the doses for immunocompromised people.5

In IBD patients, the frequency of mild adverse reactions is similar to that found in the healthy population.6 However, despite the recommendation to vaccinate against COVID-19 in these patients,7 the vaccine hesitancy rate is still high, mainly due to the fear of adverse reactions and interference with the effectiveness of used immunosuppressants in the IBD treatment.8 Given the importance of vaccine uptake in combating the COVID-19-pandemic, this study aimed to assess adherence to and the effects of the SARS-COV vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Patients and methodsStudy design and ethical aspectsThis observational, analytical, cross-sectional study was carried out in the IBD outpatient clinic of the Walter Cantídio University Hospital (HUWC) of the Federal University of Ceará, a tertiary care centre in Northeastern Brazil, from March to December 2022. We used a convenience sample of patients with IBD. The diagnosis of IBD was confirmed according to the Montreal classification, considering clinical, endoscopic, radiological, and histological criteria.9

This research followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, being analyzed by the Ethics and Research Committee under opinion number 5.227.515 according to Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council and approved under the certificate of presentation for ethical assessment n. 55207222.9.0000.5045. All patients signed a Free and Informed Consent Form before the interview.

PopulationThe study included IBD patients over 18 years of age and of both sexes who agreed to take part in the study by signing an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria were patients with severe psychiatric disorders, renal or hepatic insufficiency, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, congestive heart failure, autoimmune diseases, malignant neoplasms, pregnant women, and hospitalised patients.

Data collectionSociodemographic and clinical data were collected using a structured questionnaire. To characterize a sample, collected information about age, gender, lifestyle (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity), and level of education. Patients who reported practising less than 150min of physical activity per week were considered sedentary.10 For statistical analysis, the level of education was classified as a low level of education for patients who had no schooling or a level less than intermediate. Overweight was considered as IBM≥25kg/m211 and IBM≥27kg/m2 for adults and elderly, respectively.12

According to Brazilian guidelines, three possible vaccine technologies (mRNA vaccines – BNT162b2/Pfizer; adenovirus vector vaccine – AstraZeneca; inactivated virus – CoronaVac) we recommended for use for immunocompromised patients. Concerning the vaccination schedule, the guidelines recommended three doses with an interval of 8 weeks between each one.5 To collect the vaccination data, we checked the vaccination card to see which vaccine had been used and considered that individuals with three doses of vaccine were fully immunized. We assessed the change in vaccination schedule; those with a different type of immunizer for the third dose than the initial two doses had a heterogeneous vaccination schedule. For patients who had received at least one dose of the vaccine, we asked about post-vaccination symptoms according to the dose of the vaccine.

Adverse events after each dose of vaccine were assessed and classified by severity (non-serious adverse effects and serious adverse effects – those requiring hospitalization for at least 24h or prolongation of a current hospitalization, as well as significant dysfunction or disability, with risk of death).13 We considered non-serious adverse effects such as headache, fever or chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, arthralgia, myalgia, fatigue, enlargement of the lymph nodes, and other injection-related local symptoms.

We considered patients with COVID-19 infection confirmed by positive RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction). Data about medications for IBD used during the vaccination period were verified in medical records, categorizing without taking medication to treat IBD, synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (sulfasalazine/mesalamine/azathioprine), biologic therapy (anti-TNF/anti-integrin) and Corticosteroid therapy.

Statistical analysisThe study data was collected and managed using REDCap hosted at the Clinical Research Unit of the UFC University Hospital Complex.14 Categorical variables were described using simple frequencies and percentages, and numerical variables using mean values and standard deviation. Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Levene's test was used for homogeneity. Mann–Whitney test was used to compare means. We used Pearson's Chi-squared test to test dichotomous associations and the likelihood ratio test for associations between three variables.

Logistic regressions were carried out to estimate the Odds Ratio (OR) with the respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), assessing the factors associated with non-serious adverse effects following vaccine doses as outcome variables (dependent variable). The independent variables were previous COVID infection, IBD medications (absence of use of medications to treat IBD, DMARDs, biological therapy, and corticosteroid therapy), and type of vaccine (CoronaVac, AstraZeneca and Pfizer). Covariates with p<0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the multiple analyses, as were those of clinical importance for analysis (type of IBD, biological therapy, and corticosteroid therapy). The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0, was used for the other analyses, adopting a significance level of 5% (p<0.05).

ResultsThe sample consists of 194 IBD patients, 60.3% female (n=117) and 39.7% male (n=77), mean age of 45.3 years (SD=16.0). Most of the patients had a diagnosis of UC 56.2% (n=109), while 43.8% had CD (n=85). In terms of vaccine adherence, 78.3% of patients were vaccinated with three doses of the vaccine (n=152); 15.5% were vaccinated with two doses (n=30); 2.6% took only one dose of the vaccine (n=5) and 3.6% were not vaccinated (n=7). Females showed higher adherence to the full vaccination schedule when compared to males (p=0.024). Of those who had a complete vaccination schedule, 72.55% had a heterogeneous vaccination schedule (n=111) (Table 1).

Characterization of the general sample according to complete vaccination schedule.

| Variable | Totaln (%) | Complete vaccination schedule | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yesn (%) | Non (%) | |||

| Age. years. mean (SD) | 45.29 (±16.06) | 46.27 (±16.23) | 41.72(±15.05) | 0.094a |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 117 (60.3%) | 98 (64.5%) | 19 (45.2%) | 0.024b |

| Male | 77 (39.7%) | 54 (35.5%) | 23 (54.8%) | |

| DII | ||||

| CD | 85 (43.8%) | 65 (42.8%) | 20 (47.6%) | 0.575b |

| UC | 109 (56.2%) | 87 (57.2%) | 22 (52.4%) | |

| Low schooling | ||||

| No | 130 (67.0%) | 99 (65.1%) | 31 (73.8%) | 0.290b |

| Yes | 64 (33.0%) | 53 (34.9%) | 11 (26.2%) | |

| History of smoking | ||||

| No | 149 (76.8%) | 117 (77%) | 32 (76.2%) | 0.915b |

| Yes | 45 (23.2%) | 35 (23.0%) | 10 (23.8%) | |

| History of alcoholism | ||||

| No | 134 (69.1%) | 110 (72.4%) | 24 (57.1%) | 0.059b |

| Yes | 60 (30.9%) | 42 (27.6%) | 18 (42.9%) | |

| COVID-19 infection before vaccination | ||||

| No | 168 (86.6%) | 132 (86.8%) | 36 (85.7%) | 0.849b |

| Yes | 26 (13.4%) | 20 (13.2%) | 6 (14.3%) | |

| Presence of overweight | ||||

| No | 106 (54.6%) | 81 (53.3%) | 25 (59.5%) | 0.473b |

| Yes | 88 (45.4%) | 71 (46.7%) | 17 (40.5%) | |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Active | 56 (29%) | 44 (29.1%) | 12 (28.6%) | 0.943b |

| Sedentary | 137 (71%) | 107 (70.9%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

Source: prepared by the author.

Legend: n, Frequency; SD, Standard Deviation; IBD, Inflammatory Bowel Disease; CD, Crohn's Disease; UC, Ulcerative Rectocolitis.

The first dose of vaccine was observed association of AstraZeneca vaccine with headache (p=0.010), nausea/vomiting (p=0.020), fatigue (p=0.005), fever or chills (p<0.001), myalgia (p=0.029) and injection-related local symptoms (p=0.023). The lymphomegaly was associated with the Pfizer Vaccine (p=0.046). CoronaVac was associated with asymptomatic patients (showed no adverse effects) (p<0.001) (Table 2). In the second dose, the AstraZeneca vaccine was associated with asymptomatic patients (showed no adverse effects) (p=0.044) and in those with adverse reactions, it was associated with local symptoms (p=0.010). There was no association between the third dose of immunization and vaccine side effects. For the second dose, there were no reports of hyporexia or diarrhoea, and in the third dose there was no lymph node enlargement (Table 2).

COVID-19 vaccine effects distributed by dose, according to the immunizer used.

| Variable | Totaln (%) | Pfizern (%) | Astrazenecan (%) | Coronavacn (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First dose | 187 (100%) | 41 (21.9%) | 99 (52.9%) | 47 (25.1%) | - |

| Asymptomatic | 87 (46.5%) | 18 (43.9%) | 34 (34.3%) | 35 (74.5%) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 30 (16.0%) | 6 (14.6%) | 22 (22.2%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.010 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 6 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.020 |

| Fatigue | 20 (10.7%) | 2 (4.9%) | 17 (17.2%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.005 |

| Chills/fever | 40 (21.4%) | 5 (12.2%) | 33 (33.3%) | 2 (4.3%) | <0.001 |

| Myalgia | 30 (16.0%) | 5 (12.2%) | 22 (22.2%) | 3 (6.4%) | 0.029 |

| Local symptoms | 61 (32.6%) | 16 (39.0%) | 37 (37.4%) | 8 (17.0%) | 0.023 |

| Hyporexia | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.640 |

| Swollen lymph node | 2 (1.1%) | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.046 |

| Arthralgia | 4 (2.1%) | 1 (2.4%) | 3 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.491 |

| Diarrhoea | 4 (2.1%) | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.286 |

| Second dose | 182 (100%) | 38 (20.9%) | 98 (53.8%) | 46 (25.3%) | – |

| Asymptomatic | 114 (62.6%) | 19 (50.0%) | 60 (61.2%) | 35 (76.1%) | 0.044 |

| Headache | 8 (4.4%) | 2 (5.3%) | 5 (5.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.696 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.512 |

| Fatigue | 12 (6.6%) | 4 (10.5%) | 6 (6.1%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.505 |

| Chills/fever | 17 (9.3%) | 3 (7.9%) | 12 (12.2%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.298 |

| Myalgia | 14 (7.7%) | 3 (7.9%) | 8 (8.2%) | 3 (6.5%) | 0.941 |

| Local symptoms | 44 (24.2%) | 15 (39.5%) | 24 (24.5%) | 5 (10.9%) | 0.010 |

| Swollen lymph node | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.512 |

| Arthralgia | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (5.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.131 |

| Third dose | 152 (100%) | 121 (79.6%) | 23 (15.1%) | 8 (5.3%) | – |

| Asymptomatic | 83 (54.6%) | 69 (57.0%) | 10 (43.5%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0.472 |

| Headache | 17 (11.2%) | 14 (11.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.911 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 (3.3%) | 4 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.246 |

| Fatigue | 12 (7.9%) | 9 (7.4%) | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.880 |

| Chills/fever | 19 (12.5%) | 12 (9.9%) | 5 (21.7%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.199 |

| Myalgia | 22 (14.5%) | 16 (13.2%) | 5 (21.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.590 |

| Local symptoms | 46 (30.3%) | 33 (27.3%) | 11 (47.8%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.154 |

| Hyporexia | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.214 |

| Arthralgia | 3 (2.0%) | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.642 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.795 |

Legend: n, frequency; SD, standard deviation; likelihood ratio; p-value<0.05.

For regression analyses, patients with at least one of the variables under analysis missing data were excluded, so 185 patients participated in the analysis of the first dose, 180 patients in the second dose and 150 patients in the third dose. CoronaVac vaccine reduces the chances of non-serious adverse effects in this population by 0.28 times (OR: 0.284; 95%CI: 0.13–0.62; p=0.002). AstraZeneca vaccine increases the odds of non-serious adverse effects in IBD patients by 2.65 times (OR: 2.647; 95%CI: 1.38–5.08; p=0.003), regardless of age, gender, physical activity, overweight, use of disease-modifying drugs, immunobiologicals and corticosteroids (Table 3).

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of non-serious adverse effects during the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| First dose | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total185 (100%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | ||

| Previous infection with COVID-19a | 26 (14.1%) | 1.429 | 0.61–3.34 | 0.410 | 1.525 | 0.64–3.64 | 0.341 | 1.611 | 0.64–4.04 | 0.310 |

| Treatment of IBD | ||||||||||

| No medicationa | 30 (16.2%) | 1.578 | 0.70–3.54 | 0.268 | 1.731 | 0.76–3.95 | 0.192 | 1.702 | 0.73–3.99 | 0.220 |

| DMDa | 104 (56.2%) | 0.981 | 0.55–1.76 | 0.949 | 1.014 | 0.56–1.84 | 0.963 | 0.913 | 0.47–1.78 | 0.789 |

| Immunobiologicalsa | 49 (26.5%) | 0.847 | 0.44–1.63 | 0.619 | 0.746 | 0.38–1.47 | 0.398 | 0.837 | 0.40–1.76 | 0.638 |

| Corticotherapya | 13 (7.0%) | 0.991 | 0.32–3.07 | 0.988 | 0.923 | 0.29–2.93 | 0.891 | 0.853 | 0.26–2.82 | 0.795 |

| Vaccination scheme | ||||||||||

| CoronaVacb | 46 (24.9%) | 0.235 | 0.11–0.49 | <0.001 | 0.289 | 0.14–0.62 | 0.001 | 0.284 | 0.13–0.62 | 0.001 |

| AstraZenecab | 98 (53.0%) | 2.432 | 1.35–4.40 | 0.003 | 2.620 | 1.39–4.96 | 0.003 | 2.647 | 1.38–5.08 | 0.003 |

| Pfizerb | 41 (22.1%) | 1.26 | 0.63–2.55 | 0.514 | 0.925 | 0.42–2.02 | 0.845 | 0.893 | 0.40–1.99 | 0.897 |

Caption: n, frequency; SD, standard deviation; DMD, disease modifying drugs (Azathioprine, Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine).

Binary and multiple logistic regression, with outcome variable non-serious adverse effects in the first dose and independent variable previous COVID-19 infection, treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (no medication using DMD using immunobiologicals and on corticotherapy): Model 1 – crude; Model 2 – adjusted by age (numerical) and gender (categorical); Model 3 – adjusted by model 2+type of IBD (categorical) presence of overweight (categorical) and physical activity (categorical).

Binary and multiple logistic regression with outcome variable non-serious adverse effects in the first dose and independent variable the immunizers against COVID-19 (CoronaVac. AstraZeneca and Pfizer): Model 1 – crude; Model 2 – adjusted for age (numerical) sex (categorical) presence of overweight (categorical) and physical activity (categorical); Model 3 – adjusted by model 2+type of IBD (categorical), in use of DMD (categorical), in use of immunobiologicals (categorical) and in use of corticotherapy (categorical); p value<0.05.

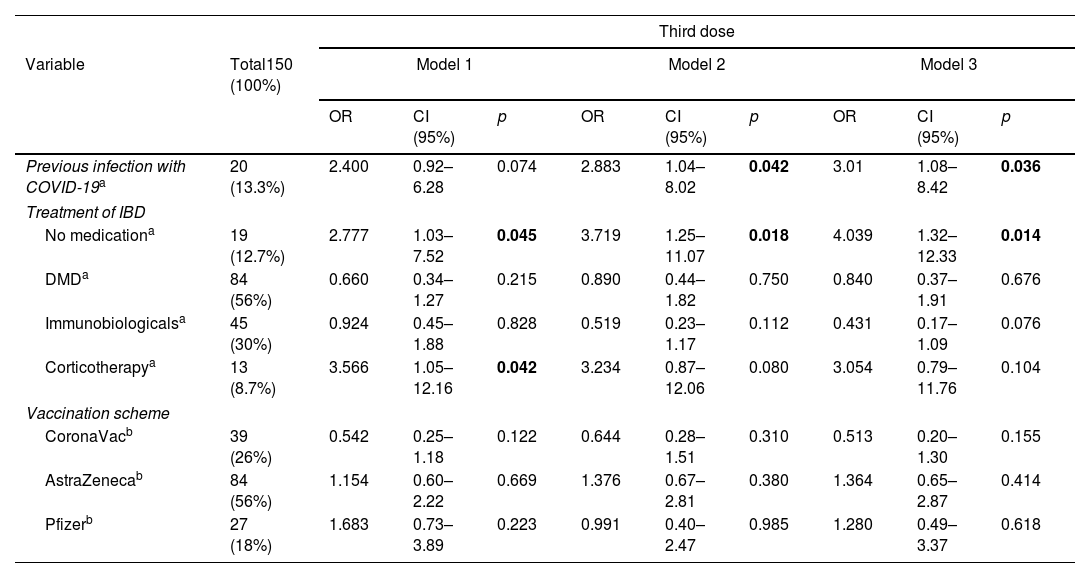

Regarding the second dose of the vaccine, there was no significant association between non-serious adverse reactions and the types of immunizers (Table 4). However, in the third dose of the vaccine, there was a direct and significant association, increasing the chances of non-serious adverse reactions by 3.01 times in patients with previous COVID-19 infection (OR: 3.01; 95%CI: 1.08–8.42; p=0.036) and 4.03 times in patients not taking medication to treat IBD (OR: 4.039; 95%CI: 1.32–12.33; p=0.014), regardless of age, gender, being overweight, practicing physical activity, type of IBD and heterogeneous vaccination schedule (Table 5).

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of non-serious adverse effects during the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Second dose | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total180 (100%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | ||

| Previous infection with covid-19a | 24 (13.3%) | 0.934 | 0.39–2.27 | 0.881 | 0.981 | 0.40–2.42 | 0.967 | 0.996 | 0.39–2.53 | 0.993 |

| Treatment of IBD | ||||||||||

| No medicationa | 25 (13.9%) | 0.706 | 0.29–1.74 | 0.448 | 0.739 | 0.30–1.85 | 0.518 | 0.799 | 0.31–2.04 | 0.639 |

| DMDa | 102 (56.7%) | 1.517 | 0.82–2.80 | 0.182 | 1.675 | 0.89–3.16 | 0.111 | 0.697 | 0.70–2.94 | 0.322 |

| Immunobiologicalsa | 50 (27.8%) | 0.748 | 0.38–1.48 | 0.405 | 0.634 | 0.31–1.29 | 0.208 | 0.771 | 0.36–1.66 | 0.507 |

| Corticotherapya | 16 (8.9%) | 0.692 | 0.23–2.09 | 0.513 | 0.577 | 0.18–1.80 | 0.344 | 0.583 | 0.18–1.88 | 0.367 |

| Vaccination scheme | ||||||||||

| CoronaVacb | 45 (25.0%) | 0.483 | 0.23–1.02 | 0.055 | 0.584 | 0.27–1.28 | 0.177 | 0.529 | 0.24–1.19 | 0.123 |

| AstraZenecab | 97 (53.9%) | 1.128 | 0.62–2.06 | 0.695 | 1.159 | 0.61–2.20 | 0.650 | 1.165 | 0.61–2.23 | 0.645 |

| Pfizerb | 38 (21.1%) | 1.784 | 0.87–3.68 | 0.116 | 1.43 | 0.64–3.16 | 0.381 | 1.552 | 0.69–3.50 | 0.290 |

Caption: n, frequency; SD, standard deviation; DMD, disease modifying drugs (Azathioprine, Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine).

Binary and multiple logistic regression, with outcome variable non-serious adverse effects in the first dose and independent variable previous COVID-19 infection, treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (no medication, using DMD, using immunobiologicals and on corticotherapy): Model 1 – crude; Model 2 – adjusted by age (numerical) and gender (categorical); Model 3 – adjusted by model 2+type of IBD (categorical), presence of overweight (categorical) and physical activity (categorical).

Binary and multiple logistic regression with outcome variable non-serious adverse effects in the first dose and independent variable the immunizers against COVID-19 (CoronaVac. AstraZeneca and Pfizer): Model 1 – crude; Model 2 – adjusted for age (numerical), sex (categorical), presence of overweight (categorical) and physical activity (categorical); Model 3 – adjusted by model 2+type of IBD (categorical), in use of DMD (categorical), in use of immunobiologicals (categorical) and in use of corticotherapy (categorical); p value<0.05.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of non-serious adverse effects during the third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Third dose | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total150 (100%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | OR | CI (95%) | p | ||

| Previous infection with COVID-19a | 20 (13.3%) | 2.400 | 0.92–6.28 | 0.074 | 2.883 | 1.04–8.02 | 0.042 | 3.01 | 1.08–8.42 | 0.036 |

| Treatment of IBD | ||||||||||

| No medicationa | 19 (12.7%) | 2.777 | 1.03–7.52 | 0.045 | 3.719 | 1.25–11.07 | 0.018 | 4.039 | 1.32–12.33 | 0.014 |

| DMDa | 84 (56%) | 0.660 | 0.34–1.27 | 0.215 | 0.890 | 0.44–1.82 | 0.750 | 0.840 | 0.37–1.91 | 0.676 |

| Immunobiologicalsa | 45 (30%) | 0.924 | 0.45–1.88 | 0.828 | 0.519 | 0.23–1.17 | 0.112 | 0.431 | 0.17–1.09 | 0.076 |

| Corticotherapya | 13 (8.7%) | 3.566 | 1.05–12.16 | 0.042 | 3.234 | 0.87–12.06 | 0.080 | 3.054 | 0.79–11.76 | 0.104 |

| Vaccination scheme | ||||||||||

| CoronaVacb | 39 (26%) | 0.542 | 0.25–1.18 | 0.122 | 0.644 | 0.28–1.51 | 0.310 | 0.513 | 0.20–1.30 | 0.155 |

| AstraZenecab | 84 (56%) | 1.154 | 0.60–2.22 | 0.669 | 1.376 | 0.67–2.81 | 0.380 | 1.364 | 0.65–2.87 | 0.414 |

| Pfizerb | 27 (18%) | 1.683 | 0.73–3.89 | 0.223 | 0.991 | 0.40–2.47 | 0.985 | 1.280 | 0.49–3.37 | 0.618 |

Caption: n, frequency; SD, standard deviation; DMD, disease modifying drugs (Azathioprine, Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine).

Binary and multiple logistic regression, with outcome variable non-serious adverse effects in the first dose and independent variable previous COVID-19 infection, treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (no medication, using DMD, using immunobiologicals and on corticotherapy) Model 1 – crude; Model 2 – adjusted by age (numerical) and gender (categorical); Model 3 – adjusted by model 2+type of IBD (categorical), presence of overweight (categorical) and physical activity (categorical).

Binary and multiple logistic regression, with outcome variable non-serious adverse effects in the first dose and independent variable the immunizers against COVID-19 (CoronaVac, AstraZeneca and Pfizer): Model 1 – crude; Model 2 – adjusted for age (numerical), sex (categorical), presence of overweight (categorical) and physical activity (categorical); Model 3 – adjusted by model 2+type of IBD (categorical), taking DMD (categorical), taking immunobiologicals (categorical), taking corticosteroid therapy (categorical) and heterogeneous vaccination schedule (categorical); p value<0.05.

In this study, the majority of IBD patients adhered to the COVID-19 vaccines, with high percentages for two doses of the vaccine (93.81%) and three doses of the immunizers (78.3%). Women showed greater adherence to the full vaccination schedule than men (p=0.024), a similar result was pointed out in a study with IBD patients,15 but contrasting results were observed globally,16 further studies are needed to elucidate this discrepancy. Furthermore, our study did not observe a relationship between low schooling and low vaccine adherence, in contrast to the study by Herman et al.,8 who observed greater hesitancy among the population with lower educational attainment.

Regarding the vaccine's side effects, it was observed no serious adverse effects, limited to the presence of local symptoms and mild systemic symptoms. Additionally, there were more side effects in the first and third doses of the immunizers. Regarding the first dose, CoronaVac showed a protective effect, while AstraZeneca increased the risk of adverse effects. As for the third dose, it was observed that the absence of IBD treatment and previous infection with COVID-19 increased the risk of adverse effects.

The literature points to high vaccine adherence in IBD patients, even in those taking immunobiologicals, with the percentages presented by the studies being over 90% for two doses and 79.1% for three doses of the vaccine, similar results to those found in the present study.15,17–19 Factors such as trust in the health professional and reliable sources of information are among the factors related to good adherence to the vaccine.20

As for adverse vaccine reactions, the results of our study were in line with the findings of other studies and were limited to mild local and systemic symptoms, such as fatigue, low-grade fever and headache.6,17 As for the relationship between adverse effects and vaccine doses, similar outcomes were observed in the scientific literature, whereupon there was a higher prevalence of adverse effects in the first vaccine dose when compared to the second dose in patients with IBD.21,22 Miyazaki et al.23 observed the presence of greater side effects in the first dose and the third dose of the vaccine when compared to the second dose, resemblant results were found in the present study. However, some articles have found contradictory results, observing more side effects in the second dose.6,15

Among the immunizers, the AstraZeneca vaccine was associated with the highest number of adverse effects in the first and second doses, while the CoronaVac vaccine was associated with asymptomatic patients. Similar results were pointed out in the healthy population.24 For the IBD group, studies are limited when it comes to comparing the types of vaccines in terms of adverse effects, especially those developed of inactive viruses, since not all countries have adhered to their use.

Regarding the factors associated with non-serious adverse effects, it was observed that for the first dose, the type of immunizer was related to the effects, CoronaVac had a protective effect, while the use of AstraZeneca increased the risk of adverse effects. As for the third dose, factors such as previous infection with COVID-19 and patients not taking medication to treat IBD showed an increased chance of adverse effects, regardless of age, gender, overweight, practising physical activity and type of IBD.

Botwin et al.6 observed that AEs were more prevalent in individuals under the age of 50, with a previous history of COVID-19 and in those with UC. In addition, patients on biological therapy were less likely to suffer side effects. Another study of IBD patients found that a history of smoking was a predictor of fever and/or chills at the first dose, while corticosteroid use was a predictor of muscle pain after the first dose of the vaccine.25

Evaluating the efficacy of vaccines in protecting against SARS-CoV-2 infection, a meta-analysis observed the following percentages of efficacy: 91.2% for Pfizer, 88.6% for AstraZeneca and 65.7% for CoronaVac. Reinforcing that all the vaccines analyzed have a good protective effect against the main outcomes related to COVID-19, especially for critical events.26 It should also be noted that IBD patients on treatment regimens need to use the third dose of immunizers, as these patients may have a reduction in antibody percentages, making them more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infections.27

However, some limitations must be considered when interpreting the results. The study included a limited number of patients. Retrospective studies are subject to information bias, which in our study was mitigated by checking the vaccination cards for the lot number and date of the vaccines. Cross-sectional studies do not allow causal relations to be inferred, and non-probabilistic sampling does not allow the results to be extrapolated beyond the study population. In addition, although the efficacy of each vaccine is a important information when considering which vaccine to recommend for IBD patients, as well as the risk of adverse effects, our study did not analyze the efficacy of each vaccine.

Nevertheless, we would like to highlight the originality of the study, since the literature is scarce in terms of articles comparing the adverse effects of vaccines with different mechanisms of action in patients with IBD.

ConclusionsThe majority of IBD patients adhered to COVID-19 vaccines, with the most prevalent being the use of two doses of the immunizers. The effects of the vaccines on these patients were limited to the presence of local symptoms and mild systemic symptoms. It should be also noted that the use of CoronaVac in the first dose had a protective effect against adverse effects, while AstraZeneca increased the risk of adverse effects. For the third dose, the absence of IBD treatment and previous COVID-19 infection were associated with an increased chance of adverse effects in these patients.

Ethical considerationsThis research followed the guideline of the Declaration of Helsinki and was analyzed by the Ethics and Research Committee under opinion number 5.227.515 according to Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council, being approved under the certificate of presentation for ethical assessment n. 55207222.9.0000.5045. All patients signed a Free and Informed Consent Form before the interview.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe present study does not present any conflict of interest.