This study aims to explore the experiences of TB-DM patients for the service barriers encountered in achieving the expected outcomes.

MethodA qualitative study was conducted between June-August 2019. TB-DM patients were identified from community health centers, and hospital TB registers Yogyakarta City, Indonesia. Fourteen adult TB-DM patients were purposively selected using criterion sampling. They were those who had been cured or already completed the intensive phase of TB treatment from 2018 to 2019. In-depth interviews were carried out using interview guides and tape-recorded. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the verbatim transcripts.

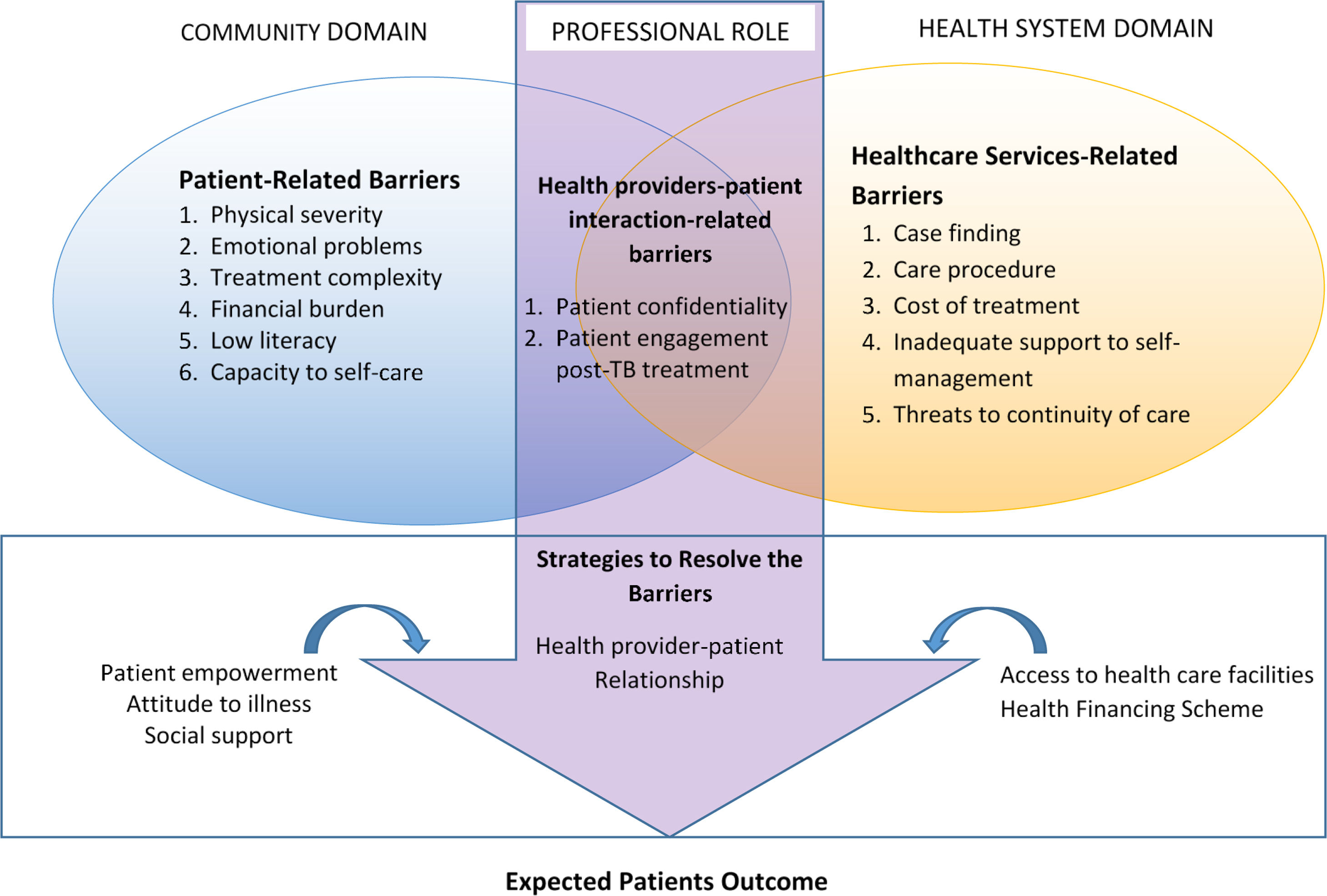

ResultsFour themes were identified: health services-related barriers, patient-related barriers, health provider-patients interaction-related barriers, and strategies to resolve the barriers.

ConclusionTB-DM patients faced a cascade of barriers with accessing TB-DM care and supports. Re-orienting the health care system for more integrated chronic care readiness and improving patients’ capacity is critical to improving the quality of care.

TB-DM is a new looming co-epidemic condition with quite high prevalence, ranging from 1.9 to 45% and Indonesia is among the top three countries of the diseases.1–3 Since a surge of multiple and chronic diseases occurs throughout the world, new approaches are needed to overcome them. Integrated care is required to resolve the problems due to the complexity of patients’ needs and duration of treatment that affects the increasing risk of the unsafe and low quality of care.1,4

The Indonesian Ministry of Health has developed the TB-DM integrated guideline, and the WHO framework for TB-DM collaboration also exists.5,6 Yet, this has not been fully implemented. Consider the patients’ perspectives to provide services according to addressing patient centered-care is one of the vital strategies for improving integrated care.7 This study aims to explore patients’ perspectives about TB-DM care, obstacles, and their experiences to get the expected outcomes in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

MethodA qualitative study drew on subjective patients’ perspectives as informants, and their experiences in managing the barriers of TB-DM comorbidity treatment was conducted.

Study settingThis study was conducted between June-August 2019 in Yogyakarta City, an urban and densely populated area located in Yogyakarta Special Region, Indonesia. With a population of 431,939 in 2019, health care services are provided by a network of 18 community health centers (CHCs), 20 hospitals and 127 clinics.8,9

Data collectionTB-DM patients were identified from TB register in all 18 CHCs and two hospitals (type D hospital, public, and private) within the period of 2018–2019. Fourteen patients were selected purposively through criterion sampling, i.e. those who had been declared cured of TB or had completed an intensive phase of TB treatment.

In-depth interviews were conducted by the first author (MA) and research assistants. MA is a woman, has a medical background with a master's in hospital management, and was trained in a qualitative research method. The research assistants have a health background and were also trained in qualitative data collection. The face-to-face interviews were either conducted in their home setting (n=10), workplace (n=1) or healthcare facilities where they received care from (n=3). The informants chose the place of interview. Each interview took about 30–60min duration, using a mixture of Indonesian and some local Javanese languages. MA piloted the interview guide to one informant before the formal interviews. All interviews were audio-recorded, and field notes were also taken during the interview process. Eleven informants were interviewed independently. During the interview, three informants were accompanied by others, such as a community health worker, the wife (without answering the questions) and the son who inevitably answered the questions.

Data analysisThe research assistants did verbatim transcriptions. Thematic analysis was applied, and codings, categories, and themes were generated using the nVivo 12.0 software.10 Data credibility was ensured during the interview process by asking questions repeatedly in a rephrased way for confirmation. Transcripts were not given to the informants but were rechecked by MA and research assistants before coding.

EthicsEthical approval was obtained from the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing at Gadjah Mada University (Ref: KE/FK/0177/EC/2019). The informants were first contacted by the TB program manager and asked to participate. The interviewers gave informed consent as written informed consent before the interviews, except one informant who gave verbal consent. At the end of the interview, respondents were given modest incentives as compensation for their time.

ResultFourteen informants were interviewed (male=6, female=8), and their age varied from 35 to 73 years. Twelve informants were first diagnosed as DM patients and had been undergoing treatment before diagnosed with TB. The remaining two informants had been first diagnosed with TB before they were found to have DM. Based on DM treatment duration, patients have undergone DM treatment for about 1–20 years. The majority of informants use insulin (n=13) with additional drugs (n=12), and only one patient takes pills only for DM treatment. As for the TB treatment, there were seven informants have completed a 6-month treatment. Another three informants have completed 9-month treatment, two informants are still in the 6-month treatment process, and the rests (two informants) are still in the 9-month treatment process. All informants were diagnosed with TB category 1. Almost all informants have poor housing with a lack of solar lighting and ventilation. Four themes obtained from the analysis of the in-depth interviews are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Theme 1: Healthcare service-related barriersPatients faced various barriers in healthcare processes. Cost of treatments, particularly the part out of pocket payment for diagnosis, treatment, and hospitalization, as well as the complexity of care procedures due to the registration, long waiting period, drug unavailability, and inadequate waiting room infrastructure accumulated barriers in accessing healthcare. The inadequate self-management support was reported around lack of dietary advice and anticipating risks (e.g., hypoglycemia, drug side effect). This conditions, along with an insufficient reminder for taking medications and scheduling systems that may influence patients capacity in dietary control and taking medicine. Moreover, the insufficient implementation of bi-directional screening resulted in TB and DM diagnosis delays, which may impede treatment. Fragmented care due to separated TB-DM clinics and low readiness of private hospitals in TB-DM collaboration services contribute not only to diagnosis delay but also to services quality and safety. The quotation below illustrates fragmented care problems across health facilities: “In a week, I feel getting worse (because of) no treatment. I told my son, “You have to say to the TB program manager at the health center that I did not get any treatment from the hospital. When my son did report, the TB program manager was upset, “You have not got anything from the hospital? Why is this hospital like that?” (Informant 14, female)

Patients with TB-DM have experienced intense barriers related to the diseases, existing socioeconomic conditions, and low literacy, leading to less collaborative actions in care processes. Regarding the disease, three categories emerged, i.e., physical severity as a consequence of multiple diseases and treatment complexity, which is interrelated with the emotional burden. Physical weakness may prevent them from visiting healthcare, worsens their mental and emotional conditions and limits their ability to have a social life and ability to work.

Their financial barriers also limit patients’ responses to the disease due to suffering from the disease despite the availability of the national social insurance scheme. Factors such as low income, inability to work, transportation costs were beyond what the insurance covers, and the barriers were perceived to be increasing with the nature of chronic diseases. These conditions are challenging in requiring long treatment duration. In general, TB-DM patients also have low health literacy, which in turn, the interaction of all patient-related barriers may affect treatment adherence, hence the clinical outcomes, as illustrated in the following quotation: “I already use insulin. To save money and not to have to visit the health center too often, I change 10 (unit) doses in the morning and ten at night to only 5-5 doses. Yesterday, I visited the health center for a routine check, the doctor asked, “Why is your blood sugar 483? Why don’t you use insulin?” (informant 7, male)

Patients reported compelling conditions from their interaction with providers. Divergent patients’ perceptions of receiving information as a result of several factors that lead to challenges in self-management support and healthcare. Patients reported that post-TB treatment engagement and monitoring were applied sporadically. Furthermore, patient doubts staff can be trusted because of professional behavior issue related to confidentiality, as emphasized in the quotation below: “A TB program manager told my mother, “Ms. X is suffering from TB, Mom.” Then my sister, like the police, asked the health center. Yes, even if I have a disease, it doesn’t matter, but don’t announce it to others.” (informant 5, female)

Patients described numerous beneficial strategies to overcome barriers while seeking treatment and uptake. Social supports, specifically family support and patient empowerment, helped alleviate their problems, yet community support linkage was still insufficient. Strengthening patients’ motivation, acceptance of illness, and appropriate health-seeking behavior are essentials to get proper treatment. Health worker's support and their communication skills created excellent relationships with patients and became enablers of successful treatment. Additionally, accessible care in time, distance, and care processes, along with social insurance scheme conjointly free TB services policy, were the aspects contribute to overcoming the obstacles, as shown in the quotation below: “I was given (TB drugs) for free, even though I do not have any health insurance, and I am not a resident of this district. All for free and very helpful for me.” (informant 9, male)

Since the integration of TB-DM services was established in 2014 in Indonesia, the collaboration of care has been partially implemented.5,11 Therefore, several aspects of service need to be improved. The integration of DM management into the TB-DM collaboration program creates challenges as well as opportunities to increase case finding and treatment.12

Our study found diverse TB-DM patients’ perceived barriers due to their condition, health system, and interrelation between them. Nevertheless, several aspects that were used as coping strategies for the obstacles and healthcare improvements were also revealed.

Like TB-DM patients, TB-HIV patients confessed their experiences due to their complicated barriers. Research by Matima et al. (2018) revealed barriers of TB-HIV patients predominantly highlighted in long waiting periods, administrative burdens, and separated clinics.13 This fragmented healthcare undermines the continuity of care since it complicates the communication and coordination lines, insufficient guidelines implementation, and the absence of interconnection and feedback mechanisms within the health system.14 Meanwhile, the problem of waiting time and administration can cause exhaustion and lowering patients’ adherence to visiting healthcare.15

Diagnostic delays and hospitals’ un-readiness of TB-DM services, as well as the private sector, were revealed. These indicated the urgency of strengthening the Public-Private Mix (PPM).16 Moreover, low economic status interacts with partial out of pocket and financial burden in accessing healthcare. Economic hardship is patient's common significant barrier.17 Therefore, the support of health financing policies and establish accessible healthcare is beneficial for patients in receiving TB-DM services as our study concedes.

Patients-related barriers compel on their clinical and socioeconomic problems. As the problems accumulate, they are lowering patient capacity.7,13 Conditions of low literacy and self-care inability may be caused or exacerbated due to lack of self-management support. Strengthening self-management support is, thus, crucial in improving patient capacity.13,18 Long engagement and monitoring of former TB patients is further needed to prevent TB relapse. At least there were three challenges of self-management integration into health care: insufficient preparation of the system, patients, and payment mechanisms.19

Family support, as found in this study, plays essential roles in the success of treatment, while linkage to community support has only been partially applied.17 This finding indicates an opportunity for care improvement by strengthening community support, as various studies proved their potential to improve chronic care successfully.20

This study suggests that it is essential to review the Ministry of Health TB-DM collaborative care guidelines and to improve providers’ and health organizations’ readiness for integrated care. Health services should be reoriented to engage the patients by strengthening their capacity and community support in order to achieve the expected outcome.

ConclusionTB-DM patients faced various levels of the barriers due to self-care burden and the healthcare system. Consolidate patients support, health system, including professional roles are essential strategies of strengthening the integrated care system to achieve better quality of care.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We want to thank the Educational Funds Agency (Indonesian Ministry of Finance) and Scholarship of Excellence for Indonesian Lecturers (Indonesian Ministry of Research and Higher Education) for funding this research. We are also grateful to the Yogyakarta City Health Agency for granting permission to this research.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 4th International Conference Hospital Administration (ICHA4). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.