The aim was to compare the incidence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 adult patients during the pandemic period versus the previous two years. Also, we described the characteristics of both cohorts of patients in pandemic period to find differences.

Material and methodsRetrospective study in our tertiary-care centre reviewing S. aureus bacteremia episodes in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients through clinical records and the Microbiology Department database.

ResultsIn 2018 and 2019, the incidence of S. aureus bacteremia episodes was 1.95 and 1.63 per 1000 admissions respectively. In the pandemic period, global incidence was 1.96 episodes per 1000 non-COVID-19 admissions and 10.59 episodes per 1000 COVID-19 admissions. A total of 241 bacteremia was registered during this pandemic period in 74 COVID-19 patients and in 167 non-COVID-19 patients. Methicillin resistance was detected in 32.4% and 13.8% of isolates from COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients respectively. In COVID-19 patients, mortality rates were significantly higher.

ConclusionsWe showed a significantly high rates of S. aureus bacteremia incidence in COVID-19 patients and higher methicillin resistance and 15-day mortality rates than in non-COVID-19 patients.

Comparar la incidencia de bacteriemias por Staphylococcus aureus en pacientes adultos COVID-19 y no-COVID-19 durante la pandemia frente a los 2 años previos. Además, describimos las características de ambas cohortes en periodo pandémico para encontrar diferencias.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo en nuestro centro de tercer nivel a través de historias clínicas y la base de datos del Servicio de Microbiología.

ResultadosEn 2018 y 2019, la incidencia de bacteriemias fue de 1.95 y 1,63 casos por cada 1.000 ingresos respectivamente. En pandemia, la incidencia global fue de 1,96 casos por cada 1.000 ingresos no-COVID-19 y de 10,59 casos por cada 1.000 ingresos COVID-19. Durante la pandemia se registraron 241 bacteriemias en 74 pacientes COVID-19 y en 167 pacientes no-COVID-19. La resistencia a meticilina se detectó en el 32,4 y 13,8% de los aislados de pacientes COVID-19 y no-COVID-19 respectivamente. En pacientes COVID-19 la mortalidad fue significativamente mayor.

ConclusionesMostramos una incidencia significativamente alta de bacteriemias por S. aureus en pacientes COVID-19, así como mayores tasas de resistencia a meticilina y mortalidad a los 15 días que en pacientes no-COVID-19.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become pandemic, and the health systems are currently dealing with unprecedented epidemic foci of severe acute respiratory infection. This clinical presentation of COVID-19 may require intensive care unit (ICU) admission and carries a high case-fatality rate.1 There are reports showing a variable prevalence in secondary infections, particularly bloodstream infections that can lead to complication in these ICU patients.1

Previous reports have shown prolonged hospital stay, morbidity and mortality in the presence of bacterial superinfections, associated with poor outcomes.2,3 Little is known about the incidence and risk of ICU acquired bloodstream infections (BSI) in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Previous studies showed clinical features of COVID-19 ICU patients, but microbiological isolates of the same species causing bacteremia are limited.1,3

The aim of this study was to compare the incidence of S. aureus bacteremia in adults in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients during these two years of the COVID-19 pandemic versus the previous two years. Also, we described demographic, clinical, and microbiological characteristics and mortality data of both cohorts of patients in pandemic period to find differences in the features of both groups.

Material and methodsThis retrospective study included adult patients admitted to our tertiary-care centre with a positive blood culture for S. aureus from February 2020 to December 2021 (pandemic period). We recovered the number of isolates of S. aureus during January 2018-December 2019 to compare incidence in non-COVID-19 patients. Only one isolate per patient was considered to define bacteremia episode. Bacteremia was nosocomial when it was diagnosed at least 48h after hospital admission. The source of infection was decided by microbiological criteria (growth of S. aureus in other clinical samples) along with clinical criteria. Demographic and clinical features were recovered from clinical records and microbiological data were recovered from the Microbiology Department database.

Microorganism identification was performed directly from positive blood cultures by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF, Bruker-Daltonics, Billerica, Massachusetts). When the identification of S. aureus was known, a PCR was performed directly from positive blood culture to detect methicillin resistance (mecA/mecC) quickly (GenomEra® MRSA/SA AC, Abacus Diagnostica, Turku, Finland). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using turbidimetry method (Vitek®2, Biomérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France).

The S. aureus isolates in other clinical samples (catheters, respiratory samples, skin and soft tissues and sterile samples) were also identified by MALDI-TOF from culture. SARS-CoV-2 was tested through several commercial RT-PCR assays on nasopharyngeal swabs.

Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test with Yates's continuity correction. Post hoc analyses were performed using Pearson's residuals with Bonferroni correction. Quantitative variables were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) and were compared by Mann–Whitney U test. Survival analyses were shown by Kaplan–Meier curves and evaluated by log-rank test. Statistical analyses were done using R (https://cran.r-project.org) and GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Holding LLC, California, USA). The dependent variable was the patient with COVID-19 versus patient with non-COVID-19 S. aureus bacteremia.

This study has the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of University Hospital La Paz with code HULP: PI-5012.

ResultsIn 2018 and 2019, the incidence of S. aureus bacteremia episodes was 1.95 and 1.63 per 1000 admissions respectively. In the two years of the pandemic period, global incidence was 1.96 episodes per 1000 non-COVID-19 admissions and 10.59 episodes per 1000 COVID-19 admissions (Table 1).

Incidence of S. aureus bacteremia episodes in COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2021) versus the previous two years (2018–2019).

| Year | Period | S. aureus bacteremia episodes | Admissions | Incidence per 1000 admissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Pre-pandemic | 94 | 48,064 | 1.95 |

| 2019 | Pre-pandemic | 80 | 48,878 | 1.63 |

| 2020 | COVID-19 | 37 | 4405 | 8.39 |

| Non-COVID-19 | 79 | 39,791 | 1.98 | |

| 2021 | COVID-19 | 38 | 2673 | 14.21 |

| Non-COVID-19 | 87 | 44,950 | 1.93 |

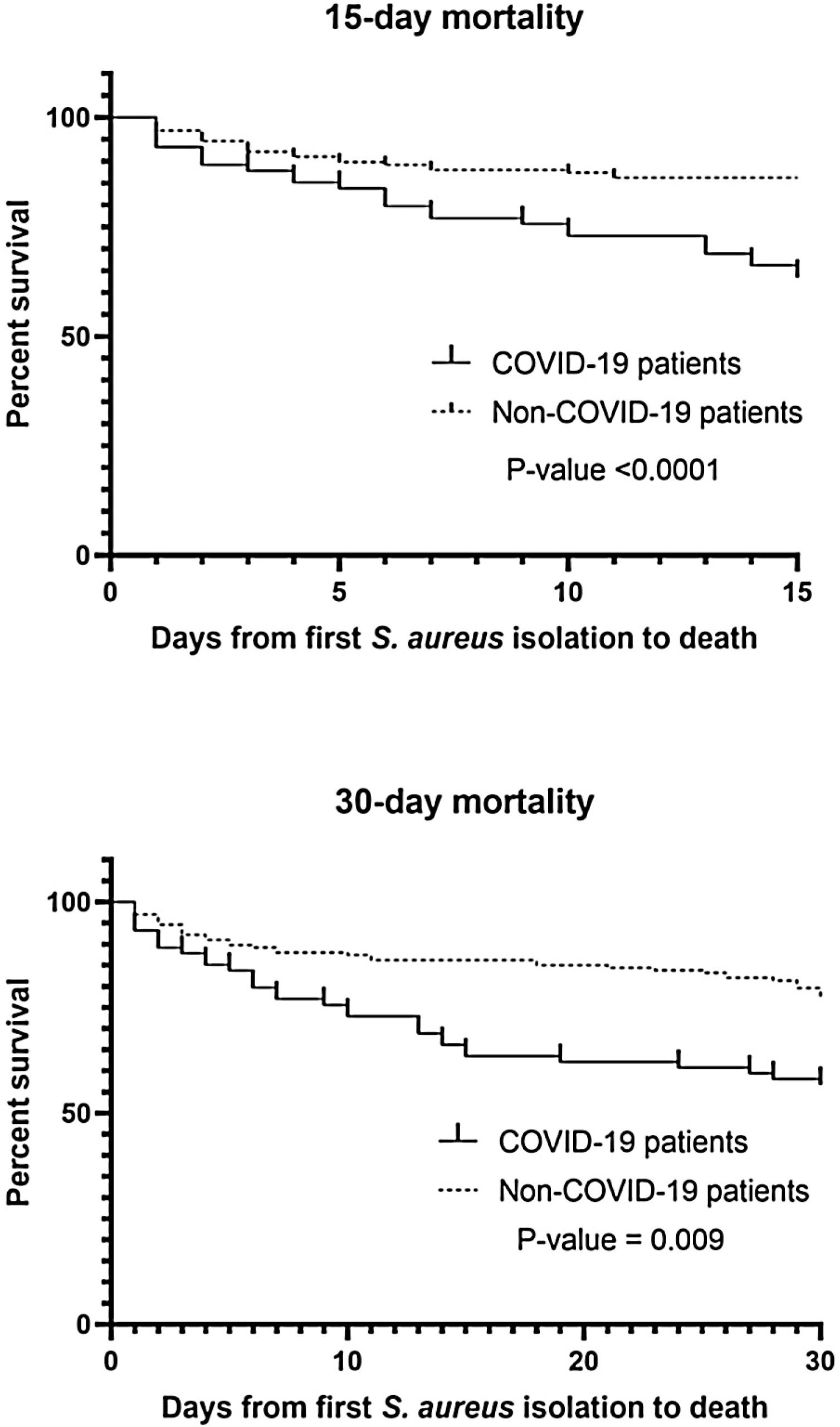

A total of 241 S. aureus bacteremia episodes were registered during this pandemic period in 74 COVID-19 patients (nosocomial bacteremia) and in 167 non-COVID-19 patients (32.9% community-acquired bacteremia and 67.1% nosocomial bacteremia). Demographic, clinical and microbiological characteristics are shown in Table 2. Age was slightly different in the two groups (median from 65.5 to 74-year-old) and predominant gender was male (61.6–65.4%). In COVID-19 patients, pulmonary was significantly the main source of bacteremia (58.1%, p<0.001) followed by endovascular source (catheter-related bacteremia, 32.4%). However, in nosocomial bacteremia of non-COVID-19 patients, endovascular was the main source of bacteremia (63.4%) followed by pulmonary (13.4%) and skin and soft tissue source (10.7%). There were only 4 cases of nosocomial bacteremia (3.6%) with intra-abdominal origin. In non-COVID-19 patients with community-acquired bacteremia the main sources were skin and soft tissue (25.4%), endovascular (23.6%) and osteoarticular (20%). Methicillin resistance was detected in 32.4% and 13.8% of Staphylococcus aureus isolates (MRSA) from COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients respectively (p=0.001). Staphylococcus aureus isolates were also recovered from other clinical samples. In nosocomial bacteremia, S. aureus was isolated from almost the half of the COVID-19 patients in respiratory samples (48.6%) in comparison with non-COVID-19 patients (p<0.001). In COVID-19 patients, mortality rates were significantly higher than non-COVID-19 patients (p<0.001 in 15-day mortality and p=0.009 in 30-day mortality). Kaplan–Meier survival curves are shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the patients with S. aureus bacteremia during the two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Characteristics | COVID-19 (N=74) | Non-COVID-19 (N=167) | p-Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosocomial bacteremia (N=74) | Community-acquired bacteremia (N=55) | Nosocomial bacteremia (N=112) | Total bacteremia (N=167) | ||

| Demographic | |||||

| Sex (male) | 47 (63.5%) | 36 (65.4%) | 69 (61.6%) | 105 (62.9%) | 1 |

| Median age and IQR (years) | 65.5 (74–54) | 74 (84–54) | 73 (83–55) | 73 (83.5–55) | 0.0047 |

| Source of infection** | |||||

| Endovascular | 24 (32.4%) | 13 (23.6%) | 71 (63.4%) | 84 (50.3%) | 0.19 |

| Pulmonary | 43 (58.1%) | 7 (12.7%) | 15 (13.4%) | 22 (13.2%) | <0.001 |

| Urinary | 0 | 4 (7.3%) | 2 (1.8%) | 6 (3.6%) | 1 |

| Osteoarticular | 0 | 11 (20%) | 3 (2.7%) | 14 (8.4%) | 0.144 |

| Skin and soft tissue | 2 (2.7%) | 14 (25.4%) | 12 (10.7%) | 26 (15.6%) | 0.074 |

| Intra-abdominal | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.6%) | 4 (2.4%) | 1 |

| Unknown | 5 (6.7%) | 6 (10.9%) | 5 (4.5%) | 11 (6.6%) | 1 |

| Methicillin-resistant s. aureus (MRSA) | |||||

| Methicillin resistance | 24 (32.4%) | 2 (3.6%) | 21 (18.7%) | 23 (13.8%) | 0.001 |

| S. aureus isolates in other clinical samples** | |||||

| Catheter | 3 (4.1%) | 10 (18.2%) | 15 (13.4%) | 25 (14.9%) | 0.067 |

| Sputum, BAS, BAL, pleural fluid | 36 (48.6%) | 2 (3.6%) | 6 (5.3%) | 8 (4.8%) | <0.001 |

| Urine | 0 | 2 (3.6%) | 5 (4.5%) | 7 (4.2%) | 0.747 |

| Articular fluid, biopsy, bone | 0 | 6 (10.9%) | 2 (1.8%) | 8 (4.8%) | 0.536 |

| Skin, wound, abscess | 1 (1.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 13 (7.8%) | 0.388 |

| Peritoneal fluid | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 1 |

BAS: bronchial aspirate; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; IQR: interquartile range.

Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test with Yates's continuity correction. Post hoc analyses were performed using Pearson's residuals with Bonferroni correction.

Quantitative variables were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) and were compared by Mann–Whitney U test.

Our incidence of S. aureus bacteremia in COVID-19 was much higher than non-COVID patients or the pre-pandemic period. All bacteremia in our COVID-19 patients were nosocomial, dissimilar to the case of the Influenza virus.4 These high values of incidence in nosocomial bacteremia were already observed in some reports.4 It is well known that bacterial co-infections in viral pneumonias are facilitated due to some mechanism such a viral modification of airway structures, immunosuppressive responses, or reduction of neutrophil recruitment because of production of cytokines.5 Moreover, it seems that the infection sequence may be partly attributable to COVID-19 treatments and management, which are direct risk factors to develop a nosocomial bacteremia due to S. aureus (central venous catheters, intubation, and corticosteroids, among others).6 In comparison, pulmonary source was the main infection source of nosocomial bacteremia in COVID-19 patients, probably related to direct pulmonary damage, in addition to mentioned above.

Among our COVID-19 patients, we observed high rates of MRSA isolation. This issue was also described by Randall et al.7 During COVID-19 pandemic, multiple measures were initiated to avoid SARS-CoV-2 transmission inside the hospital, such as specific COVID-19 wards, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) or hand hygiene and disinfection practices.7 These measures should help to control or reduce other nosocomial pathogens like MRSA. Surprisingly, despite the measures taken to control these microorganisms, in our study we have observed the opposite. This result could be because all patients with COVID-19 received broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy as prophylaxis against superinfections.8

We observed a significantly increased mortality rates in COVID-19 patients, mainly in 15-day mortality. As Adalbert et al. reported,4 this outcome is also comparable to the mortality rates in patients with S. aureus and Influenza virus co-infection. The management of the COVID-19 is mostly necessary within the first 15 days (8 to 12 days) of SARS-CoV-2 infection which is the critical period of the infection9 and as noted above, this management can be directly related to the risk of bacteremia by S. aureus and subsequent related complications, especially if hospitalization time is prolonged. In severe infection due to COVID-19, S. aureus can act synergistically increasing mortality and severity of the disease.4 As seen with Infuenza virus, COVID-19 vaccination seems imperative to reduce the severity of COVID-19 and therefore the need for prolonged hospitalization, and treatments that predispose to bacteremia due to S. aureus.10

The main limitation of this study is the retrospective design and the single-centre cohort. Also, we could not recover the detailed therapies (antibiotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs, mechanical ventilation) of the patients and we could not ensure that mortality was attributable to S. aureus bacteremia or only contributable in a severe COVID-19 infection.

In conclusion, we showed a significantly high rates of S. aureus bacteremia incidence in COVID-19 patients from pulmonary source and higher methicillin resistance (MRSA) and 15-day mortality rates than in non-COVID-19 patients. More investigations are needed to be clarified the relationship between secondary bacteremia due to S. aureus (included MRSA) in COVID-19 patients and their outcome.

Ethical considerationsThis study has the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of University Hospital La Paz with code HULP: PI-5012.

Financial disclosureNone.

Conflict of interestNone.

María Dolores Montero-Vega, María Pilar Romero, Silvia García-Bujalance, Carlos Toro-Rueda, Guillermo Ruiz-Carrascoso, Inmaculada Quiles-Melero, Fernando Lázaro-Perona, Jesús Mingorance, Almudena Gutiérrez-Arroyo, Mario Ruiz-Bastián, Jorge Ligero-López, David Grandioso-Vas, Gladys Virginia Guedez-López, Paloma García-Clemente, María Gracia Liras Hernández, Consuelo García-Sánchez, Miguel Sánchez-Castellano, Sol San José-Villar, Alfredo Maldonado-Barrueco, Patricia Roces-Álvarez, Paula García-Navarro, Julio García-Rodríguez, Montserrat Rodríguez-Ayala, Esther Ruth Almazán-Gárate, Claudia Sanz-González