COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) causes high mortality in elderly patients. Some studies have shown a benefit of statin treatment in the evolution of this disease. Since there are no similar publications in this population group, the aim of this study is to analyze in-hospital mortality in relation to preadmission treatment with statins in an exclusively elderly population of octogenarian patients.

Materials and methodsA single-center retrospective cohort study was performed including a total of 258 patients ≥80 years with hospital admission for confirmed COVID-19 between March 1 and May 31, 2020. They were divided into two groups: taking statins prior to admission (n = 129) or not (n = 129).

ResultsIn-hospital mortality due to COVID-19 in patients ≥80 years (86.13 ± 4.40) during the first wave was 35.7% (95% CI: 30.1%–41.7%). Mortality in patients previously taking statins was 25.6% while in those not taking statins was 45.7%. Female sex (RR 0.62 [0.44–0.89]; P = .008), diabetes (RR 0.61 [0.41–0.92]; P = .017) and pre-admission treatment with statins (RR 0.58 CI 95% [0.41–0.83]; P = .003) were associated with lower in-hospital mortality. Severe lung involvement was associated with increased in-hospital mortality (RR 1.45 IC95% [1.04–2.03]; P = .028). Hypertension, obesity, age, cardiovascular disease and a higher Charlson index did not, however, show influence on in-hospital mortality.

ConclusionsIn octogenarian patients treated with statins prior to admission for COVID-19 in the first wave, lower in-hospital mortality was observed.

La COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) produce una elevada mortalidad en pacientes ancianos. Algunos estudios han señalado un beneficio del tratamiento con estatinas en la evolución de esta enfermedad. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la mortalidad intrahospitalaria en relación al tratamiento previo al ingreso con estatinas en una población de pacientes octogenarios, ya que no existen estudios específicamente en este grupo de población.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo unicéntrico incluyendo un total de 258 pacientes ≥80 años con ingreso hospitalario por COVID-19 confirmada, entre el 1 de Marzo y el 31 de Mayo de 2020. Se dividieron en dos grupos: toma de estatinas previas al ingreso (n = 129) o no (n = 129).

ResultadosLa mortalidad intrahospitalaria por COVID-19 en pacientes ≥80 años (86.13 ± 4.40) durante la primera ola fue del 35.7% (IC 95%: 30.1%–41.7%). La mortalidad de los pacientes que tomaban previamente estatinas fue del 25.6% mientras que la de aquellos que no las tomaban fue del 45.7%. El sexo femenino (RR 0.62 IC 95% [0.44–0.89]; p 0.008), la diabetes (RR 0.61 IC 95% [0.41–0.92];p 0.017) y el tratamiento previo al ingreso con estatinas (RR 0.58 IC 95% [0.41–0.83]; p 0.003) se asociaron a una menor mortalidad intrahospitalaria. La afectación pulmonar grave se asoció a un aumento de la mortalidad intrahospitalaria (RR 1.45 IC 95% [1.04–2.03]; p 0.028). La hipertensión arterial, la obesidad, la edad, la enfermedad cardiovascular y un mayor índice de Charlson no mostraron sin embargo influencia sobre la mortalidad intrahospitalaria.

ConclusionesEn pacientes octogenarios tratados con estatinas previo al ingreso por COVID-19 se observó una menor mortalidad intrahospitalaria en la primera ola.

The first cases of pneumonia of unknown origin were identified in December 2019, in the city of Wuhan (Hubei, China).1 Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was sequenced as the aetiology of what is now known as COVID-19.1 In the following months, the disease achieved pandemic proportions, reaching a high incidence of cases in Spain in March 2020.

Increasing life expectancy and, in some countries, low birth rates are leading to an increase in the ageing of the population. In the case of Spain, the number of people over 65 has doubled in less than 30 years. The Spanish population over 65 years of age in 2020 was around 19.7% of the total population and those over 80 years of age around 6%. It is estimated that by 2030 these figures will continue to increase, reaching 23.6% in the first group and 7.2% in octogenarians.2

The elderly population has been one of the most affected during this pandemic with the highest mortality rates: 9.5% among 60–69-year-olds, 22.8% among 70–79-year-olds and 29.6% among those over the age of 80.3 Other studies report higher death rates in octogenarians: 60.6% mortality in males and 48.1% in females.4 A UK study describes that the risk of mortality in individuals over 80 years of age increases 20-fold compared to those aged 50–59 years.5

The comorbidities that show a higher prevalence among COVID-19 hospitalised patients and have also been associated with higher in-hospital mortality are age, male sex, active smoking, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer and acute or chronic kidney disease.6,7

Statins are lipid-lowering drugs with an anti-inflammatory profile and several studies have shown their protective effect on the progression of COVID-19 both pre-admission and in-hospital use.8–11

Given the high mortality of octogenarian patients with COVID-19 and their lower rate of admission to Intensive Care Units due to their higher burden of comorbidities, it is necessary to look for therapeutic strategies to improve their survival. In this framework, this study aims to assess the relationship between pre-admission treatment for COVID-19 with statins and in-hospital mortality in an elderly population, given that there are no studies that specifically analyse this population group.

Material and methodsStudy design and data sourceA single-centre retrospective cohort study was designed. A single-centre registry was developed that included all patients admitted for COVID-19. Patients aged ≥80 years with hospital admission for COVID-19 between 1 March and 31 May 2020 were selected from this database. Only those diagnosed by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) positive for SARS-CoV-2 were included. There were no exclusion criteria or losses to follow-up, and all patients underwent follow-up during hospital admission and were included in the statistical analysis.

Demographic characteristics (age and sex), comorbidity, laboratory data, treatments, complications and outcomes were recorded by the medical team through the electronic medical record. The Charlson comorbidity index predicts 10-year survival in patients with multiple comorbidities and was therefore calculated retrospectively at admission to stratify patients' overall comorbidity.12 The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón accepting the informed consent exemption.

Study objectivesThe primary objective was to analyse in-hospital all-cause mortality during admission for COVID-19 in relation to prior statin therapy. We also analysed which other demographic variables, cardiovascular risk factors and other comorbidities were associated with increased in-hospital mortality in an ageing population.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are described as mean and standard deviation (±SD) or median and interquartile range [p25–p75], depending on the distribution of the variable. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute value and percentages.

A first exploratory univariate analysis was performed to compare the characteristics of statin-treated and non-statin-treated patients. The Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was applied for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

To estimate the effect of treatment on in-hospital mortality, unadjusted and adjusted relative risks were estimated using modified Poisson regression models. Potential confounders include gender, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Charlson index, oxygen therapy, severe lung disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, dementia and severe chronic kidney disease. Results are expressed as relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI 95%).

All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical package SPSS and STATA. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant to observe differences between the comparative groups.

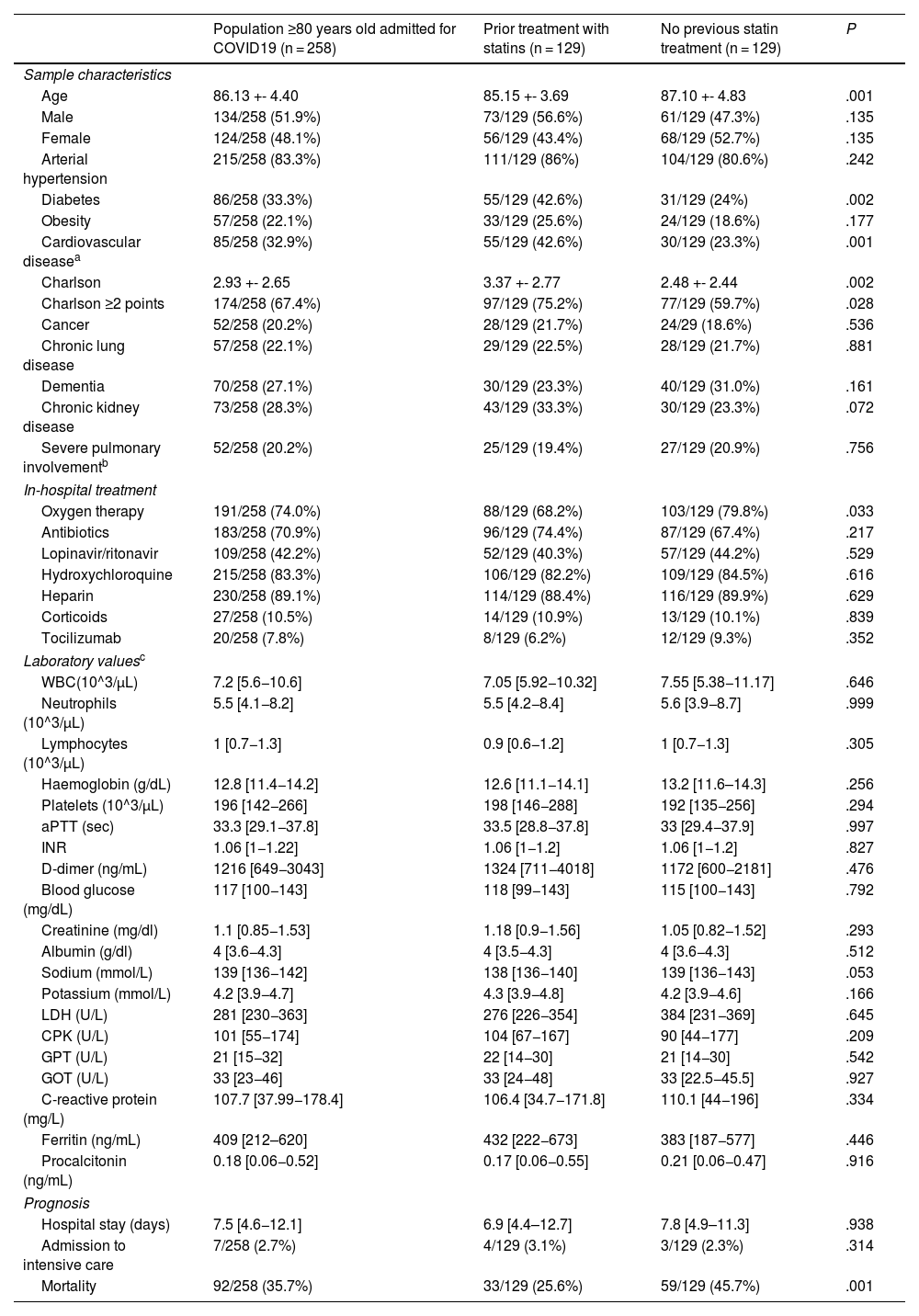

ResultsBaseline clinical characteristics of the overall sample and according to previous statin treatment.

A total of 1023 patients were admitted for COVID-19 with positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR, of whom 258 were ≥80 years old. The mean age of patients ≥80 years was 86.13 ± 4.4. The gender distribution is similar: 51.9% male and 48.1% female. The presence of comorbidities in this population is significant as 67.4% had a Charlson index ≥2 points (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, in-hospital treatment, laboratory values and prognosis of statin pretreated and non-pretreated octogenarians.

| Population ≥80 years old admitted for COVID19 (n = 258) | Prior treatment with statins (n = 129) | No previous statin treatment (n = 129) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | ||||

| Age | 86.13 +- 4.40 | 85.15 +- 3.69 | 87.10 +- 4.83 | .001 |

| Male | 134/258 (51.9%) | 73/129 (56.6%) | 61/129 (47.3%) | .135 |

| Female | 124/258 (48.1%) | 56/129 (43.4%) | 68/129 (52.7%) | .135 |

| Arterial hypertension | 215/258 (83.3%) | 111/129 (86%) | 104/129 (80.6%) | .242 |

| Diabetes | 86/258 (33.3%) | 55/129 (42.6%) | 31/129 (24%) | .002 |

| Obesity | 57/258 (22.1%) | 33/129 (25.6%) | 24/129 (18.6%) | .177 |

| Cardiovascular diseasea | 85/258 (32.9%) | 55/129 (42.6%) | 30/129 (23.3%) | .001 |

| Charlson | 2.93 +- 2.65 | 3.37 +- 2.77 | 2.48 +- 2.44 | .002 |

| Charlson ≥2 points | 174/258 (67.4%) | 97/129 (75.2%) | 77/129 (59.7%) | .028 |

| Cancer | 52/258 (20.2%) | 28/129 (21.7%) | 24/29 (18.6%) | .536 |

| Chronic lung disease | 57/258 (22.1%) | 29/129 (22.5%) | 28/129 (21.7%) | .881 |

| Dementia | 70/258 (27.1%) | 30/129 (23.3%) | 40/129 (31.0%) | .161 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 73/258 (28.3%) | 43/129 (33.3%) | 30/129 (23.3%) | .072 |

| Severe pulmonary involvementb | 52/258 (20.2%) | 25/129 (19.4%) | 27/129 (20.9%) | .756 |

| In-hospital treatment | ||||

| Oxygen therapy | 191/258 (74.0%) | 88/129 (68.2%) | 103/129 (79.8%) | .033 |

| Antibiotics | 183/258 (70.9%) | 96/129 (74.4%) | 87/129 (67.4%) | .217 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 109/258 (42.2%) | 52/129 (40.3%) | 57/129 (44.2%) | .529 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 215/258 (83.3%) | 106/129 (82.2%) | 109/129 (84.5%) | .616 |

| Heparin | 230/258 (89.1%) | 114/129 (88.4%) | 116/129 (89.9%) | .629 |

| Corticoids | 27/258 (10.5%) | 14/129 (10.9%) | 13/129 (10.1%) | .839 |

| Tocilizumab | 20/258 (7.8%) | 8/129 (6.2%) | 12/129 (9.3%) | .352 |

| Laboratory valuesc | ||||

| WBC(10^3/μL) | 7.2 [5.6−10.6] | 7.05 [5.92−10.32] | 7.55 [5.38−11.17] | .646 |

| Neutrophils (10^3/μL) | 5.5 [4.1−8.2] | 5.5 [4.2−8.4] | 5.6 [3.9−8.7] | .999 |

| Lymphocytes (10^3/μL) | 1 [0.7−1.3] | 0.9 [0.6−1.2] | 1 [0.7−1.3] | .305 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 [11.4−14.2] | 12.6 [11.1−14.1] | 13.2 [11.6–14.3] | .256 |

| Platelets (10^3/μL) | 196 [142−266] | 198 [146−288] | 192 [135−256] | .294 |

| aPTT (sec) | 33.3 [29.1−37.8] | 33.5 [28.8−37.8] | 33 [29.4−37.9] | .997 |

| INR | 1.06 [1−1.22] | 1.06 [1−1.2] | 1.06 [1−1.2] | .827 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 1216 [649−3043] | 1324 [711−4018] | 1172 [600−2181] | .476 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 117 [100−143] | 118 [99−143] | 115 [100−143] | .792 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 [0.85−1.53] | 1.18 [0.9−1.56] | 1.05 [0.82−1.52] | .293 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4 [3.6−4.3] | 4 [3.5−4.3] | 4 [3.6−4.3] | .512 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139 [136−142] | 138 [136−140] | 139 [136−143] | .053 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.2 [3.9−4.7] | 4.3 [3.9−4.8] | 4.2 [3.9−4.6] | .166 |

| LDH (U/L) | 281 [230−363] | 276 [226−354] | 384 [231−369] | .645 |

| CPK (U/L) | 101 [55−174] | 104 [67−167] | 90 [44−177] | .209 |

| GPT (U/L) | 21 [15−32] | 22 [14−30] | 21 [14−30] | .542 |

| GOT (U/L) | 33 [23−46] | 33 [24−48] | 33 [22.5−45.5] | .927 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 107.7 [37.99−178.4] | 106.4 [34.7−171.8] | 110.1 [44−196] | .334 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 409 [212–620] | 432 [222−673] | 383 [187−577] | .446 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.18 [0.06−0.52] | 0.17 [0.06−0.55] | 0.21 [0.06−0.47] | .916 |

| Prognosis | ||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 7.5 [4.6−12.1] | 6.9 [4.4–12.7] | 7.8 [4.9–11.3] | .938 |

| Admission to intensive care | 7/258 (2.7%) | 4/129 (3.1%) | 3/129 (2.3%) | .314 |

| Mortality | 92/258 (35.7%) | 33/129 (25.6%) | 59/129 (45.7%) | .001 |

Of the 258 patients ≥80 years, 129 were on pre-admission statin treatment and 129 were not, and it is a mere coincidence that the same number exists in both groups. Patients with pre-admission statin treatment were younger, had a higher percentage of diabetics, a higher percentage of cardiovascular disease and a higher Charlson index. Regarding in-hospital treatment, patients on statin pre-treatment received less oxygen therapy. No differences were detected between the groups with respect to the other in-hospital treatments for COVID-19 nor between the laboratory values studied (Table 1). No differences were observed with regard to hospital stay (Table 1).

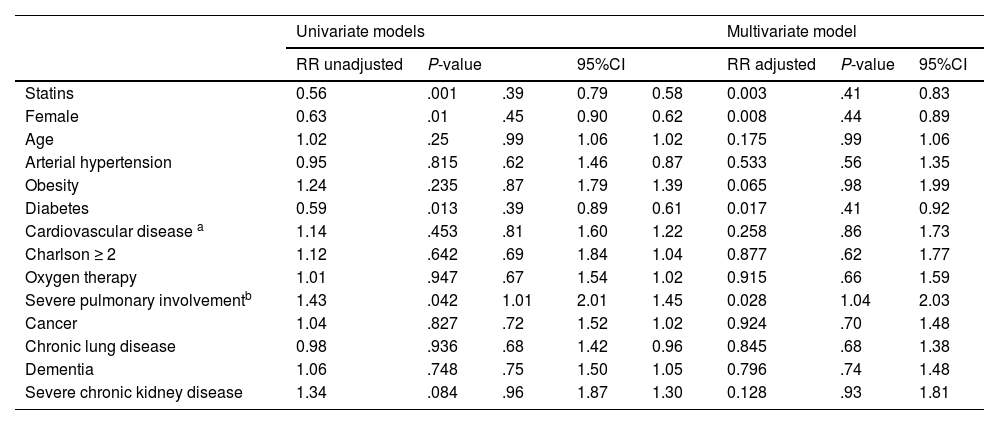

Association between pre-admission statin treatment and study outcomes.

In-hospital mortality from COVID-19 in patients ≥80 years old during the first wave was 35.7% (n = 92, 95% CI: 30.1%–41.7%). Patients in the statin pre-treatment group had an in-hospital mortality of 25.6% while those not taking statins had an in-hospital mortality of 45.7% (Table 1).

Pre-admission COVID-19 treatment of elderly patients with statins was associated with a statistically significant 42% reduction in in-hospital mortality (RR 0.58 95% CI [0.41−0.83]; P .003) after adjusting for confounding factors (Table 2) despite a higher percentage of diabetics, cardiovascular disease and higher Charlson index in this group. In fact, the number of patients that need to be treated (NNT) with statins to prevent one death from COVID-19 in the first wave in elderly patients was 5.

Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in octogenarian population admitted for COVID-19.

| Univariate models | Multivariate model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR unadjusted | P-value | 95%CI | RR adjusted | P-value | 95%CI | |||

| Statins | 0.56 | .001 | .39 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.003 | .41 | 0.83 |

| Female | 0.63 | .01 | .45 | 0.90 | 0.62 | 0.008 | .44 | 0.89 |

| Age | 1.02 | .25 | .99 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.175 | .99 | 1.06 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.95 | .815 | .62 | 1.46 | 0.87 | 0.533 | .56 | 1.35 |

| Obesity | 1.24 | .235 | .87 | 1.79 | 1.39 | 0.065 | .98 | 1.99 |

| Diabetes | 0.59 | .013 | .39 | 0.89 | 0.61 | 0.017 | .41 | 0.92 |

| Cardiovascular disease a | 1.14 | .453 | .81 | 1.60 | 1.22 | 0.258 | .86 | 1.73 |

| Charlson ≥ 2 | 1.12 | .642 | .69 | 1.84 | 1.04 | 0.877 | .62 | 1.77 |

| Oxygen therapy | 1.01 | .947 | .67 | 1.54 | 1.02 | 0.915 | .66 | 1.59 |

| Severe pulmonary involvementb | 1.43 | .042 | 1.01 | 2.01 | 1.45 | 0.028 | 1.04 | 2.03 |

| Cancer | 1.04 | .827 | .72 | 1.52 | 1.02 | 0.924 | .70 | 1.48 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0.98 | .936 | .68 | 1.42 | 0.96 | 0.845 | .68 | 1.38 |

| Dementia | 1.06 | .748 | .75 | 1.50 | 1.05 | 0.796 | .74 | 1.48 |

| Severe chronic kidney disease | 1.34 | .084 | .96 | 1.87 | 1.30 | 0.128 | .93 | 1.81 |

As for the other factors analysed in our series, female sex (RR 0.62 [0.44−0.89]; P .008) and diabetes (RR 0.61 [0.41−0.92]; P .017) were associated respectively with a 38% and 39% reduction in in-hospital mortality. Severe lung involvement was associated with a 45% increase in in-hospital mortality (RR 1.45 [1.04–2.03]; P .028). With regard to the other factors analysed, no influence on in-hospital mortality was observed (Table 2).

DiscussionThis study shows that patients ≥80 years of age who prior to admission for COVID-19 were on statin therapy had a 42% reduction in in-hospital mortality. Our results are consistent with other studies suggesting the benefit of statins in COVID-19.8–11 The difference, however, is that this study assesses the protective effect of statins in an exclusively elderly population.

Statins as a protective factor during SARS-CoV-2 infectionCOVID-19 mortality in patients ≥80 years of age ranges from 20% to 60% in different studies.3–5 A meta-analysis of cohorts in China revealed elevated mortality rates in the general population with cardiovascular disease (10.5%), diabetes (7.3%) and hypertension (6%) compared to those without comorbidities (0.9%).13 Mortality in our study was 35.7%, in a population with a mean age of 86 years, high prevalence of arterial hypertension (83.3%), diabetes (33.3%), cardiovascular disease (32.9%) and comorbidities (67.4% with Charslon index ≥2 points).

Pre-COVID-19 studies have shown that statin therapy can improve prognosis in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.14 Therefore, the possibility that statin therapy might be beneficial in the progression of COVID-19 was first examined.

One of the first studies to demonstrate this protective association was the retrospective cohort of 13,981 patients by Zhang et al. of whom 1219 were on statin therapy. The statin group showed a lower 28-day all-cause mortality of 5.2% compared to 9.4% in the non-statin group (adjusted HR 0.58 95% CI [0.43−0.80]; P < .001).8 In this study, the statin group also had older age, hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease, as well as higher levels of neutrophils, procalcitonin and D-dimer.8

The meta-analysis by Diez-Arocutipa et al.,15 including 147,824 patients on statin therapy and SARS-CoV-2 infection aged 44–70 years showed lower mortality in patients on chronic statin therapy.15 Another meta-analysis of 63,537 patients with COVID-19 showed that statin use was again associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality as well as in the need for invasive mechanical ventilation, but not in the need for admission to Intensive Care Units.16 In fact, the group on chronic statin therapy had an even lower mortality suggesting that they should not be discontinued during admission.16

Regarding the usefulness of statin treatment prior to admission or during admission, a beneficial effect has been suggested in both scenarios. The study by Zhang et al. showed a reduction in all-cause mortality with statin treatment in the first 28 days after admission (HR 0.58 [95% CI 0.43−0.80] P < .001).8 Torres-Peña et al. showed that those who were pre-treated with statins and maintained them during admission also had a lower all-cause mortality (OR 0.67 [95% CI 0.54−0.83] P < .001).9 The publication by Daniels et al.10 showed that pre-admission statin treatment was associated with a reduction in the risk of severe COVID (OR 0.29 [95% CI 0.11−0.71] P < .01).

Regarding the effect of statins in an elderly population with COVID-19, a retrospective study conducted in nursing homes with a small sample of 154 patients describes that a higher proportion of patients on chronic statin treatment went through the infection without symptoms.17

On the other hand, another aspect to take into account in the elderly population is frailty. Frailty is an age-related syndrome characterised by increased vulnerability caused by reduced homeostasis in several organ systems that has been associated with increased mortality.18 Retrospective studies have shown an increase in in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 admissions in those patients with greater frailty and higher burden of comorbidities as well as in those with moderate or severe dependency.18,19

Frailty includes not only functionality but also the nutritional status of the patient. Multiple nutritional scales include albumin among their parameters.20 The meta-analysis by Silva-Fhon et al. showed that elderly patients with higher albumin levels were associated with lower sarcopenia.21 There are also studies associating high Charlson indices (≥2) with poorer nutritional status.20 Despite the limitation of the lack of available frailty and nutritional scales in our study due to its retrospective nature and the context of the health crisis in which it was developed, we can mention that both groups have similar albumin levels on admission and that the Charlson index is higher in the group on statin treatment.

The effect of comorbidities as measured by the Charlson index is documented in Kuswardhani et al. meta-analysis which shows an increase in COVID-19 mortality of 16% for each point on the Charlson comorbidity index as well as an increase in mortality and disease severity at high Charlson comorbidity index values.22

Our study, with an exclusively elderly population, showed that the group that was on pre-admission statin treatment had a higher percentage of diabetics, cardiovascular disease and a higher burden of comorbidities (higher Charlson index), which, as we have mentioned, are factors associated with a worse COVID-19 outcome.6,7 This is not surprising given that patients at risk of or with cardiovascular disease routinely take these drugs. However, surprisingly, patients who were on pre-admission statin treatment not only offset the poor prognosis associated with their multiple diseases but also had lower in-hospital mortality than those who were not taking statins and who had fewer comorbidities. This makes us think of the potential beneficial effect of these drugs, especially in the elderly population.

Potential protective mechanisms of statins against SARS-CoV-2The protective effect of statins on the development of COVID-19 could be due to their pleiotropic effects.23 SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 protein on the surface of lung cells, which facilitates its entry into the cell.23 It has been postulated that reduced ACE2 activity is responsible for the excessive inflammatory response of COVID-19.23 Statins can increase ACE2 levels as reported with atorvastatin, rosuvastatin and pravastatin.23 These facts lead us to hypothesise that statins inhibit the renin-angiotensin system by reducing the pro-inflammatory effects of angiotensin II.23 Inactivation of the inflammasome by statins is also involved in the anti-inflammatory effect.24

One of the common findings in patients with COVID-19 is coagulopathy: elevated D-dimer, thrombocytopenia and prolonged prothrombin time.23 Patients with COVID-19 also reported a higher number of thrombotic events.23 Some studies suggest an antithrombotic effect of statins by decreasing thrombin generation through reduced tissue factor expression, platelet inactivation or even decreased levels of D-dimer.23

Recently the Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology Group together with the College of Basic Cardiovascular Science of the European Society of Cardiology has published a position paper on the role of the endothelium in the pathophysiology of COVID-19.25 The hyperinflammatory and prothrombotic state of COVID-19 leads to a critical involvement of the vascular endothelium.25 In particular, there is evidence that SARS-CoV-2 directly infects endothelial cells.25 SARS-CoV-2 infection causes endothelial dysfunction at multiple levels leading to increased inflammatory activation, cytokine storm, leukocyte infiltration, increased vascular permeability, thrombosis, platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cell apoptosis.25 Statins improve endothelial dysfunction in patients with or at risk of cardiovascular disease.23 Nitric oxide overexpression, inhibition of pro-inflammatory pathways, platelet inactivation and antithrombotic properties as effects associated with statins could be mechanisms by which a protective effect on endotheliitis developed with COVID-19 could be derived.25

On the other hand, the lipid-lowering effect could also play a beneficial role as SARS-CoV2 requires lipid metabolism to create the viral cell membrane to increase viral replication. Thus, lipid-lowering drugs such as statins could play a role in inhibiting viral replication.26

Randomised clinical trials with statins in the progression of COVID-19INSPIRATION-S is the only randomised clinical trial evaluating statin therapy in COVID-19.27 This study analysed 587 patients of whom 290 were assigned to receive 20 mg of atorvastatin from admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) until one month later and 297 patients received placebo.27 The primary endpoint of the study was the combined response of arterial or venous thrombosis, extracorporeal oxygenation membrane therapy or all-cause mortality at 30 days; there was no difference between groups (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.58–1.22).27 Statin treatment was shown to be safe: no differences in myopathy or liver enzyme levels.27

However, the INSPIRATION-S27 differs greatly from our study. Firstly, the age of the patients is much younger (57 years compared to 86 years in our sample), secondly, all patients were admitted to the ICU (in our series only 2.7% given the age and comorbidities of the elderly population) and thirdly, the chronology of statin treatment (from admission to the ICU in severe disease versus chronic treatment prior to admission, thus assuming a protective effect at an early stage of infection).

In summary, there is evidence of a potential protective effect of statins on COVID-19 given their anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic and lipid-lowering effects. There are now other randomised clinical trials that will be able to demonstrate the benefit suggested in the retrospective studies (NCT04380402).

Study limitationsThe study was conducted on a prospectively completed database of all patients with COVID admitted to our hospital for the express purpose of clinical research. This design is strongly determined by the time when the study is conducted, the beginning of COVID-19 in Spain (the so-called first wave), which led to an unprecedented health crisis. The specific objective of assessing the possible protective effect of statins on the basis of the information collected was postulated at a later stage and is therefore not protected against confounding and it is not possible to casually attribute the differences in outcome to any particular factor; nor do we claim that these results can be reproduced by other investigators. Another limitation derived from the massive number of patients is that it was not possible to apply geriatric scales to assess frailty, functional or nutritional status on admission, which would be factors to take into account in the elderly population. Furthermore, neither the type of statin nor its doses were available.

ConclusionsCOVID-19 causes high mortality in elderly patients. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit of statins on the progression of COVID-19 in the general population. This is the first study to assess the relationship between pre-admission statin treatment on COVID-19 progression in an exclusively elderly population. In this study, the in-hospital mortality of patients previously taking statins was 25.6% while that of those not taking statins was 45.7%. Pre-admission statin therapy in octogenarian patients showed a statistically significant 42% reduction in in-hospital mortality (RR 0.58 95% CI [0.41−0.83]; P = .003) despite being a group with higher cardiovascular risk and more comorbidities.

Authorship/collaboratorsC. Jiménez Martínez, V. Espejo Bares, V. Artiaga de la Barrera, C. Marco Quirós conceived the idea and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. E. Pérez Fernández carried out the statistical analysis. I. Monedero Sánchez, A. I. Huelmos Rodrigo, C. García Jiménez, P. González Alirangues, L. Hernando Marrupe, R. del Castillo Medina, R. Campuzano Ruiz collaborated in data collection. M.L. Martínez Mas and J. Botas Rodríguez carried out a critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Isabel Monedero Sánchez, Ana Isabel Huelmos Rodrigo, Carlos García Jiménez, Pablo González Alirangues, Lorenzo Hernando Marrupe, Roberto del Castillo Medina and Raquel Campuzano Ruiz from the Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón.