The COVID-19 pandemic has had a great effect on the management of chronic diseases, by limiting the access to primary care and to diagnostic procedures, causing a decline in the incidence of most diseases. Our aim was to analyze the impact of the pandemic on primary care new diagnoses of respiratory diseases.

MethodsObservational retrospective study performed to describe the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of respiratory diseases according to primary care codification. Incidence rate ratio between pre-pandemic and pandemic period was calculated.

ResultsWe found a decrease in the incidence of respiratory conditions (IRR 0.65) during the pandemic period. When we compared the different groups of diseases according to ICD-10, we found a significant decrease in the number of new cases during the pandemic period, except in the case of pulmonary tuberculosis, abscesses or necrosis of the lungs and other respiratory complications (J95). Instead, we found increases in flu and pneumonia (IRR 2.17) and respiratory interstitial diseases (IRR 1.41).

ConclusionThere has been a decrease in new diagnosis of most respiratory diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha tenido efecto sobre el seguimiento de las enfermedades crónicas. Nuestro objetivo fue analizar el impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 en los nuevos diagnósticos respiratorios en atención primaria.

MetodologíaEstudio observacional retrospectivo realizado para describir el impacto de la COVID-19 sobre la incidencia de diagnósticos respiratorios en atención primaria. Se ha calculado la tasa relativa de incidencia entre el periodo prepandémico y el pandémico.

ResultadosHallamos una reducción en la incidencia de patología respiratoria (IRR 0,65) durante la pandemia. Al comparar los distintos grupos de enfermedades (CIE-10), encontramos una reducción significativa en el número de nuevos casos durante la pandemia, excepto en el caso de tuberculosis pulmonar, abscesos o necrosis pulmonar y otras complicaciones respiratorias. Por otro lado, se detectaron incrementos en nuevos diagnósticos de gripe y neumonía (IRR 2,17) y enfermedades respiratorias intersticiales (IRR 1,41).

ConclusiónSe ha producido un descenso en el número de nuevos diagnósticos de la mayoría de las enfermedades respiratorias durante la pandemia por COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a great impact on the management of chronic diseases by limiting the access to primary care and to several diagnostic procedures. Several authors have analyzed the consequences of the pandemic on the incidence rates of different conditions, describing an overall decline in new diagnoses of most diseases.1–3

Our aim was to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care new diagnoses, focusing on respiratory diseases other than lung cancer.

MethodsSettingThis was an observational retrospective study performed to describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care new diagnosis (diagnoses not previously codified for one patient) of respiratory diseases. The study was conducted with administrative data obtained from the primary care system in the Northern Metropolitan Region (one of the health administrative regions of Catalonia, Spain), representing 63.4% of all primary health teams in the region (77 primary care centers and 26 local practices). The Northern Metropolitan Region covered 1.393.366 patients according to 2021 data.

Pandemic period definitionFor the purpose of the study, we defined as pandemic period months from March 14th 2020 to March 13th 2021. Thus, pre-pandemic period was defined from March 14th 2019 to March 13th 2020.

New diagnosisThe way we identified new diagnoses has already been described in a previous article.4 We flagged a diagnosis as new if within the list of diagnoses associated to a certain patient's visit with primary healthcare team there is a diagnosis that is not in the list of the preexisting active diagnoses of the patient. Diagnoses were also considered to be new if they were added to the list of active diagnoses across patient visits, between two consecutive visits. Diagnoses and health problems were recorded by physicians using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10).

Definition of respiratory diseaseWe used all diseases classified as group J (respiratory system diseases) in the ICD-10. Arbitrarily, we also included in the analysis as respiratory diseases G47 (Obstructive sleep apnea) and A15 (pulmonary tuberculosis) codes.

Statistical analysisIncidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals between pre-pandemic and pandemic period were calculated using the ir command of the version 15 of STATA. Our results were corrected for multiple testing.

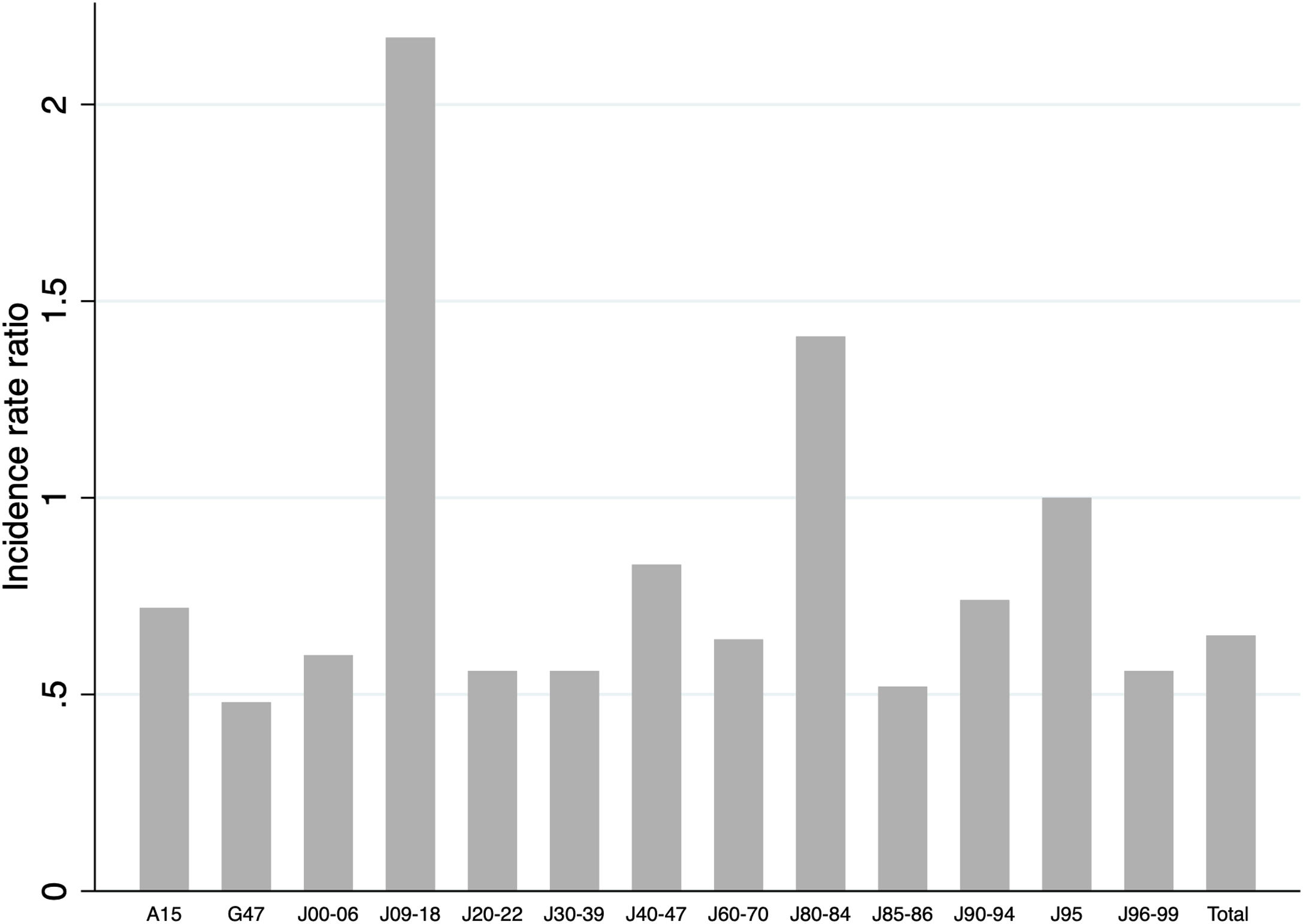

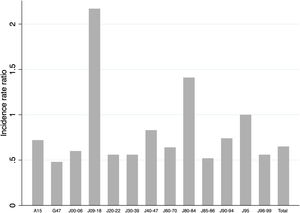

ResultsThe IRR of new respiratory diagnoses between periods can be seen in Fig. 1. When we compared the global incidence of new respiratory diagnoses between the pandemic and the pre-pandemic period, we found a decrease in the incidence (IRR 0.65, 95% CI 0.64–0.66, p=0.0000). When we compared the different groups of diseases according to ICD-10, we found a significant decrease in the number of new cases during the pandemic period, except in the case of pulmonary tuberculosis (A15), abscesses or necrosis of the lungs (J85-86) and other respiratory complications (J95). On the other hand, we found increases in new diagnoses of flu and pneumonia (excluding COVID-19 infection) (J09-18) (IRR 2.17, 95% CI 1.89–2.50, p=0.0000) and respiratory interstitial diseases (IRR 1.41, 95% CI 1.13–1.76, p=0.0015).

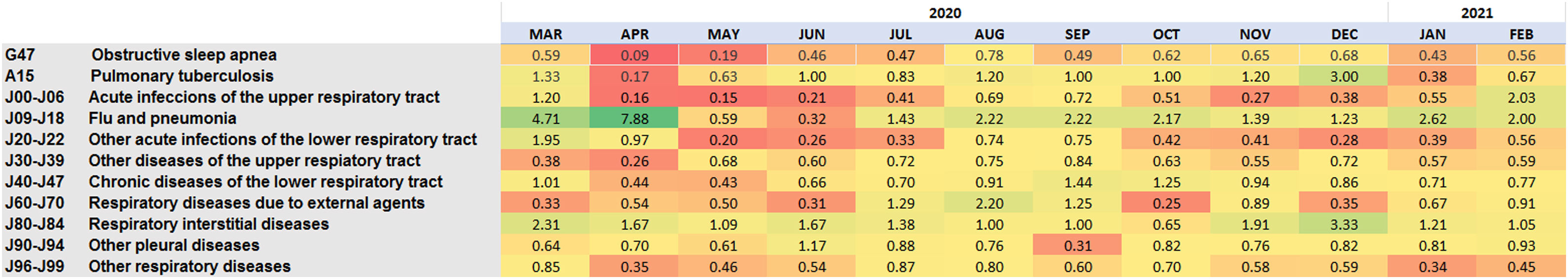

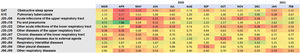

The heatmap (Fig. 2) presents by month the ratio of new diagnosis during the pandemic period compared to new diagnosis during the pre-pandemic period by ICD-10 groups. Interestingly, we found a peak in new diagnoses of flu and pneumonia in March and April of 2020, with a relevant decrease in the IR of all the other conditions except for respiratory interstitial diseases. In those conditions with decreased number of new diagnoses during the pandemic period, the ratio very rarely reached the levels of the same month previous to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The heatmap presents by month (x-axis) the ratio of new diagnosis during the pandemic period compared to new diagnosis during the pre-pandemic period by ICD-10 groups (y-axis). Severe drops in diagnosis in the pandemic period are in red, similar diagnoses are in yellow, and increases in diagnoses are in green.

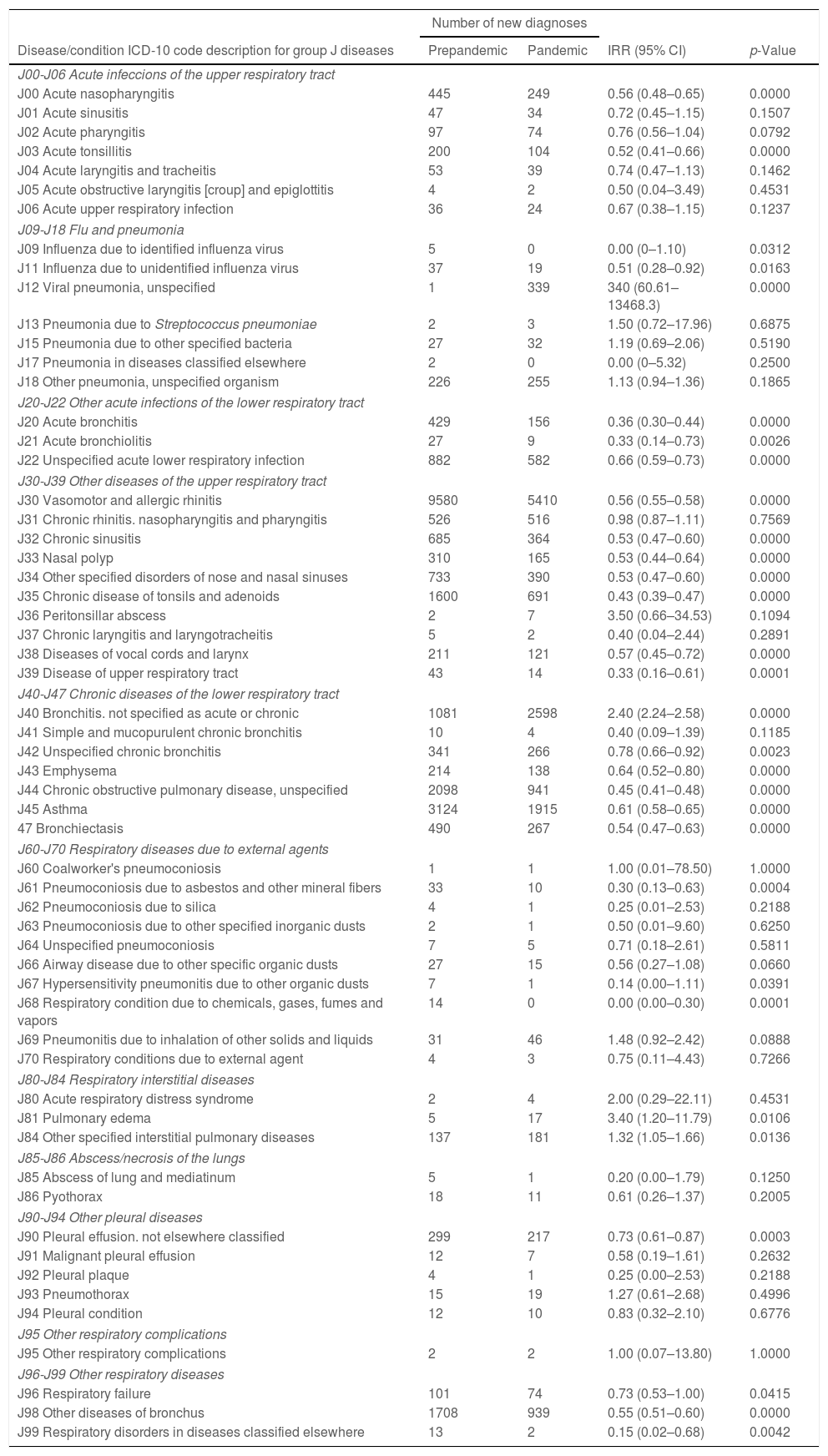

The number of the new diagnosis of respiratory diseases for the pre-pandemic and the pandemic period and its IRR can be seen in Table 1.

This table shows the absolute number of new diagnoses for each period, and the IRR of new respiratory diagnoses between pre-pandemic and pandemic periods.

| Number of new diagnoses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease/condition ICD-10 code description for group J diseases | Prepandemic | Pandemic | IRR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| J00-J06 Acute infeccions of the upper respiratory tract | ||||

| J00 Acute nasopharyngitis | 445 | 249 | 0.56 (0.48–0.65) | 0.0000 |

| J01 Acute sinusitis | 47 | 34 | 0.72 (0.45–1.15) | 0.1507 |

| J02 Acute pharyngitis | 97 | 74 | 0.76 (0.56–1.04) | 0.0792 |

| J03 Acute tonsillitis | 200 | 104 | 0.52 (0.41–0.66) | 0.0000 |

| J04 Acute laryngitis and tracheitis | 53 | 39 | 0.74 (0.47–1.13) | 0.1462 |

| J05 Acute obstructive laryngitis [croup] and epiglottitis | 4 | 2 | 0.50 (0.04–3.49) | 0.4531 |

| J06 Acute upper respiratory infection | 36 | 24 | 0.67 (0.38–1.15) | 0.1237 |

| J09-J18 Flu and pneumonia | ||||

| J09 Influenza due to identified influenza virus | 5 | 0 | 0.00 (0–1.10) | 0.0312 |

| J11 Influenza due to unidentified influenza virus | 37 | 19 | 0.51 (0.28–0.92) | 0.0163 |

| J12 Viral pneumonia, unspecified | 1 | 339 | 340 (60.61–13468.3) | 0.0000 |

| J13 Pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2 | 3 | 1.50 (0.72–17.96) | 0.6875 |

| J15 Pneumonia due to other specified bacteria | 27 | 32 | 1.19 (0.69–2.06) | 0.5190 |

| J17 Pneumonia in diseases classified elsewhere | 2 | 0 | 0.00 (0–5.32) | 0.2500 |

| J18 Other pneumonia, unspecified organism | 226 | 255 | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) | 0.1865 |

| J20-J22 Other acute infections of the lower respiratory tract | ||||

| J20 Acute bronchitis | 429 | 156 | 0.36 (0.30–0.44) | 0.0000 |

| J21 Acute bronchiolitis | 27 | 9 | 0.33 (0.14–0.73) | 0.0026 |

| J22 Unspecified acute lower respiratory infection | 882 | 582 | 0.66 (0.59–0.73) | 0.0000 |

| J30-J39 Other diseases of the upper respiratory tract | ||||

| J30 Vasomotor and allergic rhinitis | 9580 | 5410 | 0.56 (0.55–0.58) | 0.0000 |

| J31 Chronic rhinitis. nasopharyngitis and pharyngitis | 526 | 516 | 0.98 (0.87–1.11) | 0.7569 |

| J32 Chronic sinusitis | 685 | 364 | 0.53 (0.47–0.60) | 0.0000 |

| J33 Nasal polyp | 310 | 165 | 0.53 (0.44–0.64) | 0.0000 |

| J34 Other specified disorders of nose and nasal sinuses | 733 | 390 | 0.53 (0.47–0.60) | 0.0000 |

| J35 Chronic disease of tonsils and adenoids | 1600 | 691 | 0.43 (0.39–0.47) | 0.0000 |

| J36 Peritonsillar abscess | 2 | 7 | 3.50 (0.66–34.53) | 0.1094 |

| J37 Chronic laryngitis and laryngotracheitis | 5 | 2 | 0.40 (0.04–2.44) | 0.2891 |

| J38 Diseases of vocal cords and larynx | 211 | 121 | 0.57 (0.45–0.72) | 0.0000 |

| J39 Disease of upper respiratory tract | 43 | 14 | 0.33 (0.16–0.61) | 0.0001 |

| J40-J47 Chronic diseases of the lower respiratory tract | ||||

| J40 Bronchitis. not specified as acute or chronic | 1081 | 2598 | 2.40 (2.24–2.58) | 0.0000 |

| J41 Simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis | 10 | 4 | 0.40 (0.09–1.39) | 0.1185 |

| J42 Unspecified chronic bronchitis | 341 | 266 | 0.78 (0.66–0.92) | 0.0023 |

| J43 Emphysema | 214 | 138 | 0.64 (0.52–0.80) | 0.0000 |

| J44 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified | 2098 | 941 | 0.45 (0.41–0.48) | 0.0000 |

| J45 Asthma | 3124 | 1915 | 0.61 (0.58–0.65) | 0.0000 |

| 47 Bronchiectasis | 490 | 267 | 0.54 (0.47–0.63) | 0.0000 |

| J60-J70 Respiratory diseases due to external agents | ||||

| J60 Coalworker's pneumoconiosis | 1 | 1 | 1.00 (0.01–78.50) | 1.0000 |

| J61 Pneumoconiosis due to asbestos and other mineral fibers | 33 | 10 | 0.30 (0.13–0.63) | 0.0004 |

| J62 Pneumoconiosis due to silica | 4 | 1 | 0.25 (0.01–2.53) | 0.2188 |

| J63 Pneumoconiosis due to other specified inorganic dusts | 2 | 1 | 0.50 (0.01–9.60) | 0.6250 |

| J64 Unspecified pneumoconiosis | 7 | 5 | 0.71 (0.18–2.61) | 0.5811 |

| J66 Airway disease due to other specific organic dusts | 27 | 15 | 0.56 (0.27–1.08) | 0.0660 |

| J67 Hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to other organic dusts | 7 | 1 | 0.14 (0.00–1.11) | 0.0391 |

| J68 Respiratory condition due to chemicals, gases, fumes and vapors | 14 | 0 | 0.00 (0.00–0.30) | 0.0001 |

| J69 Pneumonitis due to inhalation of other solids and liquids | 31 | 46 | 1.48 (0.92–2.42) | 0.0888 |

| J70 Respiratory conditions due to external agent | 4 | 3 | 0.75 (0.11–4.43) | 0.7266 |

| J80-J84 Respiratory interstitial diseases | ||||

| J80 Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 2 | 4 | 2.00 (0.29–22.11) | 0.4531 |

| J81 Pulmonary edema | 5 | 17 | 3.40 (1.20–11.79) | 0.0106 |

| J84 Other specified interstitial pulmonary diseases | 137 | 181 | 1.32 (1.05–1.66) | 0.0136 |

| J85-J86 Abscess/necrosis of the lungs | ||||

| J85 Abscess of lung and mediatinum | 5 | 1 | 0.20 (0.00–1.79) | 0.1250 |

| J86 Pyothorax | 18 | 11 | 0.61 (0.26–1.37) | 0.2005 |

| J90-J94 Other pleural diseases | ||||

| J90 Pleural effusion. not elsewhere classified | 299 | 217 | 0.73 (0.61–0.87) | 0.0003 |

| J91 Malignant pleural effusion | 12 | 7 | 0.58 (0.19–1.61) | 0.2632 |

| J92 Pleural plaque | 4 | 1 | 0.25 (0.00–2.53) | 0.2188 |

| J93 Pneumothorax | 15 | 19 | 1.27 (0.61–2.68) | 0.4996 |

| J94 Pleural condition | 12 | 10 | 0.83 (0.32–2.10) | 0.6776 |

| J95 Other respiratory complications | ||||

| J95 Other respiratory complications | 2 | 2 | 1.00 (0.07–13.80) | 1.0000 |

| J96-J99 Other respiratory diseases | ||||

| J96 Respiratory failure | 101 | 74 | 0.73 (0.53–1.00) | 0.0415 |

| J98 Other diseases of bronchus | 1708 | 939 | 0.55 (0.51–0.60) | 0.0000 |

| J99 Respiratory disorders in diseases classified elsewhere | 13 | 2 | 0.15 (0.02–0.68) | 0.0042 |

ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; IRR: incidence rate ratio.

We found a decrease in new diagnoses during the pandemic period. Data on group J40-47 (chronic diseases of the lower respiratory tract) were especially relevant. The number of new diagnoses was lower either for emphysema (J43, IRR 0.64, 95% CI 0.52–0.80, p=0.0000), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (J44, IRR 0.45, 95% CI 0.41–0.48, p=0.0000), asthma (J45, IRR 0.61, 95% CI 0.58–0.65, p=0.0000), and bronchiectasis (J47, IRR 0.54, 95% CI 0.47–0.63, p=0.0000).

DiscussionOur study describes a decrease in primary care new diagnoses of respiratory diseases for most of the groups, except for those referring to respiratory infections (flu and pneumonia, especially in the initial period of the pandemic) and respiratory interstitial diseases.

These findings are in line with previous reports, that despite not being exclusively focused on respiratory diseases, had described a decline in respiratory diseases in general2,4 or specific decreases on incidence rates of asthma or COPD.3,5 Despite not focusing on new diagnoses, several authors have described a decrease in primary care visits for chronic conditions such as respiratory diseases, hospital admissions due for respiratory diseases6 or exacerbations of chronic respiratory diseases7 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There can be several explanations to these findings. First, the use of face masks and social distance has been useful to reduce viral infections, which can produce exacerbations of respiratory diseases such as asthma or COPD. Secondly, the pandemic impacted usual medical activities by limiting the access to most diagnostic procedures. For example, sleep laboratories decreased their diagnostic capacity in order to minimize the risk for infection8 and, simultaneously, the performance of lung function testing was restricted to the diagnosis, differential diagnosis and before interventional procedures or surgery, always with a previous RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2. Thirdly, depending on the severity of the pandemic, sometimes it has been difficult to access primary care and specialized doctors. Chest physicians changed their usual clinical activities, being actively involved in the management of patients with respiratory failure and SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, and several visits end exams were postponed or canceled.

Healthcare centers could have been seen as dangerous places, and people could have been afraid of seeking for health care due to the fear of getting infected. In other cases, people could have perceived their problems as less important when compared with the overall situation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.9

What will be the consequences of this decrease in respiratory diagnoses on the prognosis of respiratory conditions is still to be determined. Respiratory care physicians will face two main challenges in the post-pandemic era. First of all, they will have to care for those patients with respiratory symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Secondly, they will have to treat all those patients with respiratory conditions which have been missed or worsen during the pandemic. In a recent study by del Cura-Gonzalez et al., the authors described that the annual incidence rate of COPD showed an under-average recovery after the first wave of the pandemic, unlike the case of heart failure,10 and suggested that healthcare system should contemplate specific actions for the groups at highest risk.

The main limitation of our study is the fact that it is based on codification in primary care. Patients requiring being hospitalized who did not attend their primary care physician after discharge, or those who died in hospital, have not been included in the analysis. Thus, acute conditions with elevated mortality could be underestimated.

Secondly, it is a retrospective study which has been carried out only in one health administrative region of Catalonia.

In conclusion, there has been a decrease in new diagnosis of most respiratory diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the real clinical impact of this situation is still unknown. Large-scale real-life studies will make it possible to evaluate the long-term consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on the respiratory diseases management.

Take home messageThere has been a decrease in new diagnosis of most respiratory diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients without diagnose will not receive the optimal treatment, and this can have long-term effects.

Conflict of interestThe authors do not have any financial or personal relationships with people or organizations that could inappropriately influence their work in the present article.

The authors would like to thank the Department of Information Systems for their help with the acquisition of data.