Chylous ascites is an uncommon form of ascites (<1% of the total) that is characterised by a high triglyceride concentration >200 mg/dl. There are no recent publications on its epidemiology, although a previous study reported an incidence of one case per 20,000 hospitalisations.1

We present the case of a 78-year-old male with arterial hypertension on diuretic treatment, with atrial flutter, anticoagulated and with chronic kidney disease.

The patient reported a three-month history of clinical symptoms of asthenia, a progressive increase in waist circumference and weight gain. The physical examination revealed moderate ascitic signs with the palpation of a large abdominal mass and oedema in the lower limbs.

The blood test results were: creatinine 1.65 mg/dl, GOT 24 U/l, GPT 16 U/l, bilirubin 1.2 mg/dl, CRP 116 mg/l, LDH 269 U/l, Fe 28 μg/dl, transferrin 163 mg/dl, IS 12%, B12 167 pg/mL, ESR 54, alpha-1 globulin 6.7%, alpha-2 globulin 18.7%, gammaglobulin 7.9%, beta-2 microglobulin 10.4 mg/dl.

The ultrasound study showed moderate ascites, as well as a large solid-looking mass attached to the mesentery.

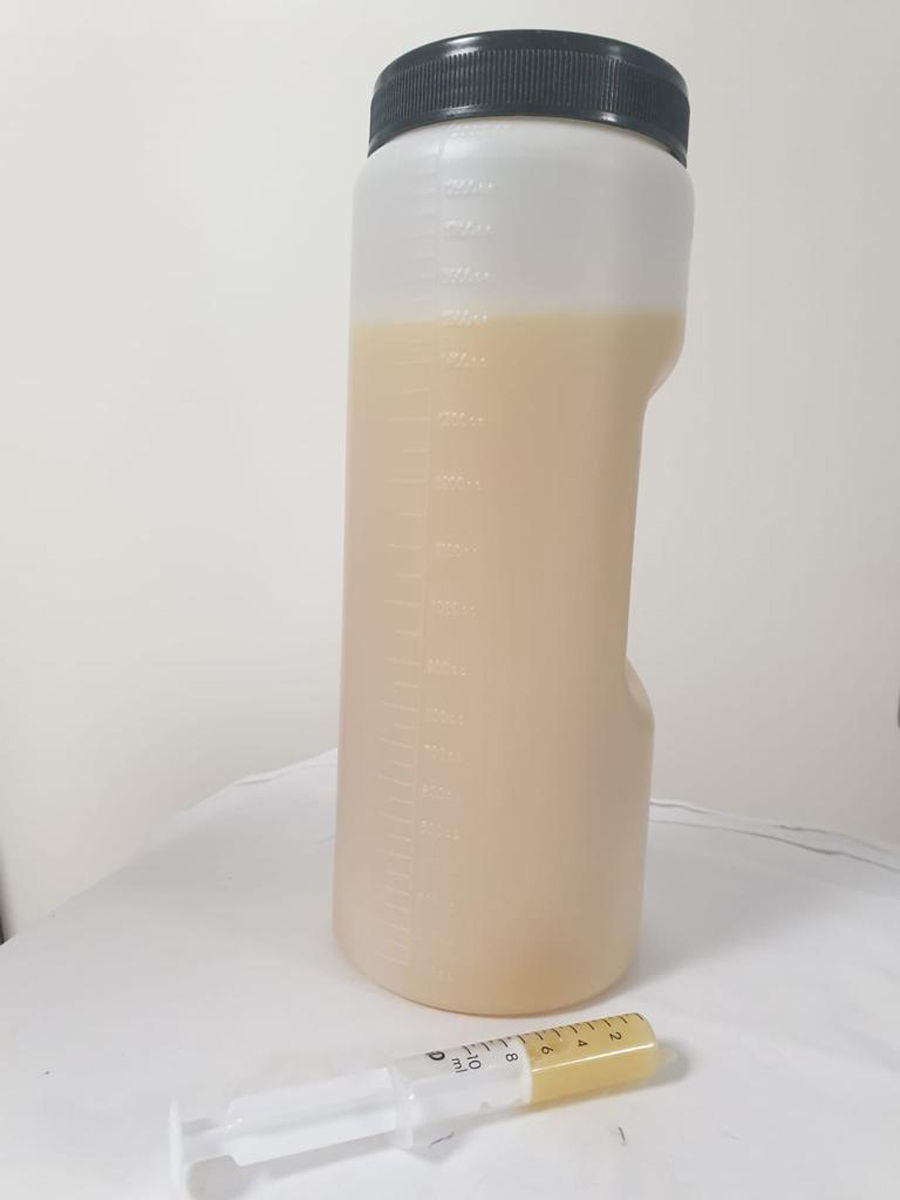

Following a diagnostic paracentesis (Fig. 1), the ascitic fluid analysis was as follows: glucose 120 mg/dl, proteins 5.6 g/dl, albumin 2.9 g/dl, LDH 139 U/l, amylase 20 U/l, adenosine deaminase (ADA) 34, triglycerides 1,236 mg/dl, red blood cells 4,000, leukocytes 1,950 (lymphocytes 39%, neutrophils 24%).

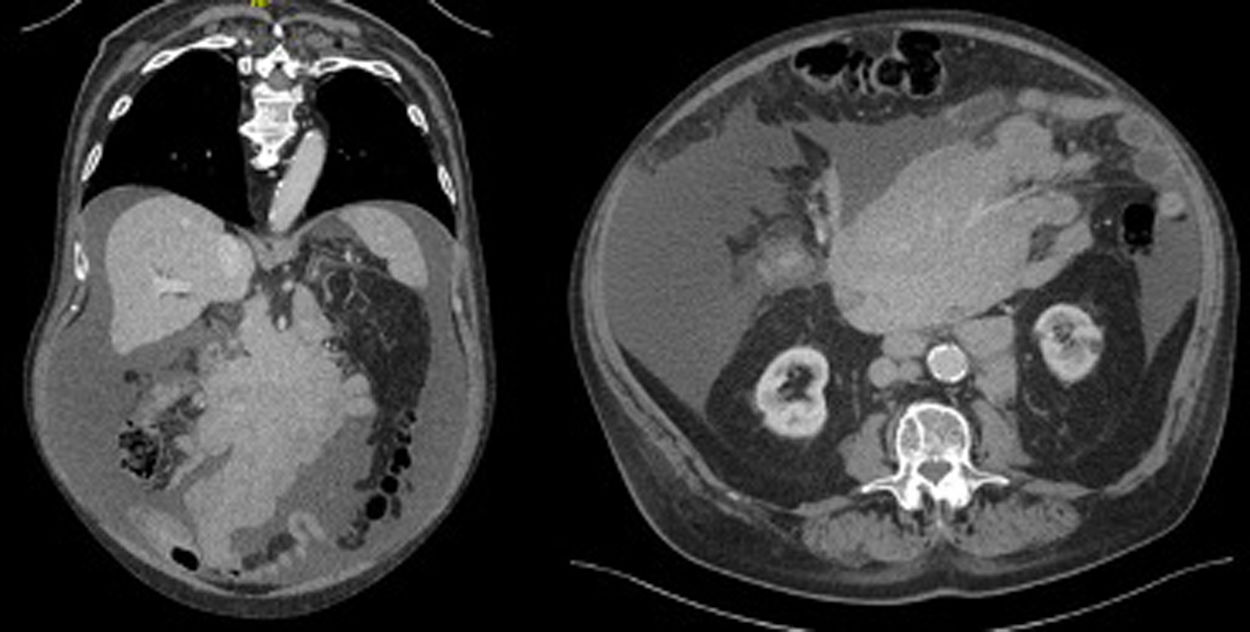

The cytology was negative for malignancy and the cultures ruled out any infectious cause. The study was completed by a chest-abdomen-pelvis CT scan (Fig. 2), which showed a major solid mass in the mesentery of 11 × 17 × 26 cm and a retroperitoneal adenopathic conglomerate continuing from the aforementioned mass, consistent with a lymphoproliferative process.

A CT-guided percutaneous biopsy was performed, resulting in the pathological diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma GC phenotype on follicular lymphoma.

The patient was given nutritional supplements with medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) and R-mini-CHOP chemotherapy, and the ascites resolved after eight weeks of treatment.

Chylous ascites is caused by a disruption of the lymphatic system. Browse et al.2 propose three mechanisms, depending on the aetiology:

- -

Obstruction and disruption of the thoracic duct following trauma, surgery or radiation therapy, autoimmune or infectious aetiology (tuberculosis, filariasis) or through an increase in lymphatic production (cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease).

- -

Invasion and destruction of the lymphatic system secondary to a malignant process. In descending frequency: lymphomas, neuroendocrine tumours, sarcomas, leukaemias, solid tumours.

- -

Congenital dilation of the lymphatic ducts. For example, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome.

In a systematic review3 of 190 patients with non-traumatic chylous ascites, the most common cause was lymphatic anomalies (32%), followed by malignant diseases (17%), cirrhosis (11%) and mycobacteria infections (15%). Lymphoma accounted for at least one third of the cases of malignant chylous ascites.

With regard to diagnosis, besides the medical history, physical examination and blood tests, the performance of a paracentesis is mandatory. A turbid-milky looking ascitic fluid is obtained, with a concentration of triglycerides >200 mg/dl. A complete study of the ascitic fluid must be performed, including total proteins, albumin, LDH, glucose, amylase, triglycerides, ADA (if tuberculosis is suspected), cell count, Gram staining, culture and cytology. Radiological examinations play a fundamental role in the diagnosis of chylous ascites, particularly when there is no history of recent trauma or surgery, since they make it possible to rule out an underlying malignant cause.

Treatment of the causal condition is fundamental from the therapeutic standpoint. Although evidence on the specific treatment of chylous ascites is limited, a protein-rich, low-fat diet supplemented with MCT is recommended to reduce the production of chyle. In the event of treatment failure, somatostatin and its analogue octreotide (dose 100 ug/8 h sc), normally combined with total parenteral nutrition, have proven to be effective, particularly in the management of post-surgical chylous ascites.4 Surgery is a recourse for salvage therapy.

In patients with cirrhosis, besides diuretic treatment, which continues to be the cornerstone, orlistat, a reversible inhibitor of gastric and pancreatic lipase, reduces triglyceride levels in the ascitic fluid, with subsequent improvement in ascites.5 Treatment with MCT in advanced cirrhosis is not recommended. In the event of resistance to medical treatment, the use of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is known to be safe and effective in this patient subgroup.

Please cite this article as: Gorroño Zamalloa I, Markuleta Iñurritegi M, Urtasun Arlegui L, Orive Calzada A, Ascitis quilosa secundaria a linfoma difuso de células grandes B. A propósito de un caso, Gastroenterología y Hepatología. 2022;96:488–489.