People suffering from mental health disorders have an increased risk of morbidity secondary to reduced physical health. Physical health assessment is therefore key to improving the quality of care given to psychiatric patients. Our longitudinal study was divided into three stages and evaluated the comprehensiveness of physical examination in patients admitted to the Forensic Unit at the National Mental Health Hospital in Malta. Documentation was audited before and after the implementation of change. The introduction of a standardised physical health checklist at a National Forensic Unit resulted in improved physical health assessment and documentation.

People with mental health issues have a reduced life expectancy and are at increased risk of disabling medical conditions.1 Besides addressing lifestyle issues and better managing the side effects of psychotropic treatment, physical health screening is an essential part of the health care that is required.2 Physical assessment in Psychiatric admissions can provide essential and helpful diagnostic information that will guide management and subsequently improve outcome. The physical assessment is also crucial in order to ensure that patients admitted to a Mental Health hospital are physically stable. The aim of this study was to assess and evaluate the comprehensiveness of the physical examination in acute patients admitted to the Forensic Unit at the National Mental Health Hospital in Malta. The study also aimed to implement change and optimise physical assessment in patients being admitted.

MethodsA study on the quality and thoroughness of the physical health assessment and physical examination of newly admitted psychiatric patients within the Forensic Unit of Mount Carmel Hospital, the national mental health hospital in Malta, was performed. The work was the first of its kind locally. A complete audit cycle was performed to measure the effectiveness of introducing a new standardised form for assessing physical health in forensic psychiatric patients. The longitudinal study was divided into three stages.

Pre-intervention stageAn initial retrospective audit was conducted to determine whether patients admitted to the Forensic Unit had a physical health assessment and a physical examination performed prior to admission. The case notes for all patients admitted between December 2018 and January 2019, both inclusive, were analysed retrospectively to assess whether details on parameter charting, physical examination, frontline testing for drugs of abuse and the appropriate use of drugs of abuse withdrawal scores were documented. All identifying patient and clinician information was removed. The case notes of forty-eight consecutive admissions were audited (Table 1).

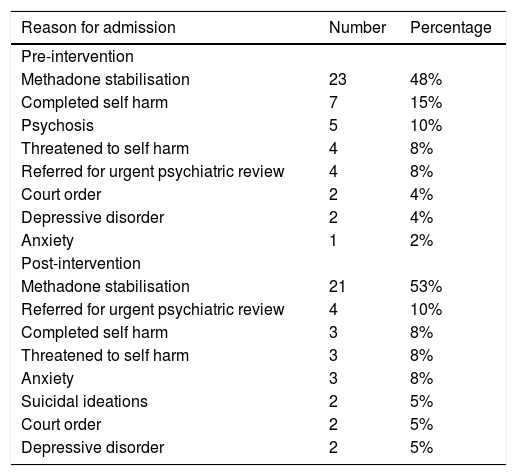

Reasons for admission to psychiatric forensic unit.

| Reason for admission | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | ||

| Methadone stabilisation | 23 | 48% |

| Completed self harm | 7 | 15% |

| Psychosis | 5 | 10% |

| Threatened to self harm | 4 | 8% |

| Referred for urgent psychiatric review | 4 | 8% |

| Court order | 2 | 4% |

| Depressive disorder | 2 | 4% |

| Anxiety | 1 | 2% |

| Post-intervention | ||

| Methadone stabilisation | 21 | 53% |

| Referred for urgent psychiatric review | 4 | 10% |

| Completed self harm | 3 | 8% |

| Threatened to self harm | 3 | 8% |

| Anxiety | 3 | 8% |

| Suicidal ideations | 2 | 5% |

| Court order | 2 | 5% |

| Depressive disorder | 2 | 5% |

A standardised physical health checklist was specifically created for Forensic Unit admissions. The form was designed based on the input of forensic psychiatrists, forensic psychiatry resident specialists, psychiatry trainees and foundation year doctors. The form included the following sections: parameters on admission (blood pressure, respiratory rate, heart rate, temperature and oxygen saturations), general appearance examination, cardiovascular examination, respiratory examination, abdominal examination, and neurological examination including the Glasgow Coma Scale. The form also included sections specific to forensic psychiatry admissions; details regarding history of substance abuse, psychotropic drug abuse, symptoms of withdrawal effects, symptoms of intoxication and any physical concerns at the time of assessment.

The form was distributed to all psychiatrists, medical doctors and nurses working within the unit and was implemented at the end of February 2019 after the completion of the pre-intervention audit. Medical practitioners working within the Forensic unit were instructed to complete the physical health assessment sheet on first medical contact at the Forensic Unit. The practitioners were advised to postpone the physical assessment and examination in patients who refused to be examined and to document this accordingly.

Post-intervention stageA second audit was carried out using the same criteria as the initial audit after the introduction of the physical health assessment sheet. The case notes for all patients admitted between March 2019 and April 2019, both inclusive, were analysed retrospectively. Details on parameter charting, physical examination, frontline testing for drugs of abuse and the appropriate use of withdrawal scores were analysed during both audit phases. The case notes of forty-one consecutive admissions were audited (Table 1).

Approval from hospital authorities, the Departmental Chairman and Forensic Psychiatry Consultants was obtained prior to data collection and before the introduction of the Physical Health Checklist. Guidelines from the University of Malta Research Ethics Committee (UREC) were followed and the study did not require UREC permission for data collection. The authors ensured high quality and integrity in all stages. Confidentiality and anonymity of all patients and healthcare professionals were respected.

ResultsIn the pre-intervention stage, 48 patients were admitted to the Forensic Unit at Mount Carmel Hospital. In the post-intervention stage, the number of admissions was 41. The case notes from all admissions were studied. In both stages of the audit cycle, the most common reason for admission to the Forensic Unit was for methadone stabilisation. Other reasons for admission included threats to deliberate self harm, completed deliberate self harm, suicidal ideations, patients under court order and patients suffering from acute psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety and psychosis.

Before the implementation of the physical health assessment sheet, parameters were documented in 65% of case notes. After implementing the physical checklist, parameters were documented in 98% of all admitted patients.

In the pre-intervention stage the cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal system examinations were performed and the findings documented in the file in 27% (13 of 48) of admitted patients. The findings from the neurological examination were documented in the files of 17% (8 of 48) of patients. Pupil assessment was documented in 17% of patients (8 of 48). The Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) was documented in 0% of admissions.

The newly implemented physical checklist was filled in 98% of admissions. The findings from cardiovascular and respiratory were documented in 98% (40 of 41) of cases. The abdominal examination findings were documented in 93% (38 of 41) of patients. The findings from the neurological system examination were documented in 90% (37 of 41) admitted patients. Pupils were assessed and the Glasgow Coma Score was documented in 98% (40 of 41) of admissions.

Before implementation of the physical checklist, the urine frontline for drugs of abuse was taken and documented in the notes in 98% of admissions. Opiates were detected in the urine of 29% of admissions and the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal (COW) scale was started in 100% of these patients. In the re-audit phase, the urine frontline for drugs of abuse was taken and documented in 100% of admissions. Opiates were detected in the urine of 24% of admissions and the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal (COW) scale was started in 100% of these patients.

DiscussionPeople with mental illnesses are at a higher risk of poor physical health when compared to the general population.3 Hence interventions to identify and manage physical health problems in people with mental illnesses is an important area of study and practice. A key part of this is physical examination on admission to a mental facility.4 Besides giving a more holistic view of a patient’s overall health it is also associated with improved patient outcome since knowledge of medical comorbidities allows better planning of psychiatric treatment and avoidance of drug interactions.5

Based on the pressing and widely acknowledged need to improve physical health amongst in-patients a pro-forma physical health checklist was designed and implemented as a screening tool for all the newly admitted psychiatric patients within the Forensic Unit. Use of systematic physical examinations has been shown to improve morbidity and mortality amongst patients with mental illness.6 The initial results show that despite its importance, physical health screening and monitoring are not given the necessary value by health care professionals. Pre-intervention results revealed that physical examination was performed in less than a third of the patients. Any form of healthcare screening was inconsistent as well as inadequate. Possible reasons for this include staff related factors such as workload and inherent perception that physical examination is of low priority in the admission to a mental health facility. Lack of confidence in physical examination by psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees could also contribute.7 Other possible reasons include patient related factors such as aggressive or agitated patient behaviour which could possibly hinder physical examination.8

The results highlight the need for increased staff education and training regarding the importance of physical examination. Mental care workers are in a privileged position to identify and refer appropriately medical conditions amongst patients with mental health issues since they are often the only medical contact for these patients.9 As shown by the post-intervention results, the introduction of a pro-forma, lead to physical examination being performed in more patients. Such intervention besides reminding health care professionals of the importance of physical examination offers a template to do so. Future interventions to improve the screening process is to include the pro-form as part of the routinely used psychiatric assessment booklet instead of a seperate form. Other efforts to encourage physical examination include establishment of hospital guidelines including a stipulated time for medical history and physical examination to be complete for newly admitted patients.

ConclusionImproving the physical health of patients with mental illness is an important area of study for mental health care professionals and healthcare in general. The initial results of our research show that physical examination on admission was somewhat limited. Following the introduction of a pro-forma the completion rate improved significantly. Future areas of research include studying the effect of such interventions on long term health outcomes.

Ethical considerationsApproval from hospital authorities, the Departmental Chairman and Forensic Psychiatry Consultants was obtained prior to data collection and before the introduction of the Physical Health Checklist. Guidelines from the University of Malta Research Ethics Committee (UREC) were followed and the study did not require UREC permission for data collection. The authors ensured high quality and integrity in all stages. Confidentiality and anonymity of all patients and healthcare professionals were respected.

ContributorsAll authors contributed to the study design. GX and KA worked on the initial audit. GX, KA and JB worked on the design and implementation of the physical health checklist. All authors worked on the re-audit and data collection. A review of the current literature was conducted by GX, JB and KA. The report was written by all authors. All authors read and approved the final version submitted for publication. GX is the guarantor.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors do not have any conflict of interest related to the study and there has been no form of financial support.