We aimed to study the psychopathological profile in different disorders across the psychotic continuum and to demonstrate that negative symptoms are not so rare in delusional disorder, as it was traditionally considered.

MethodsThis was an observational study utilizing a sample of 112 patients with a psychotic disorder (delusional disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder). The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used to ascertain psychopathological symptoms. One-way ANOVA analyses and post hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni correction were carried out to compare illness duration and PANSS indices. Additionally, t-tests were performed to explore the difference between positive and negative symptomatology in the delusional disorder group.

ResultsClinical groups were statistically similar in General PANSS scores, but they differed significantly, in Positive, Negative and Composite PANSS scores. Negative symptoms existed in all three psychotic categories, although they were less prominent in delusional disorder. Positive symptoms were also present in all three categories but were significantly more apparent among schizoaffective disorder patients.

ConclusionsOur results support the notion of a psychopathological gradient across the psychosis continuum from patients with delusional disorder, at one extreme of the scope, to those with schizoaffective disorder, at the other. More importantly, we have found out that in delusional disorder, negative symptoms do exist and are of similar intensity as positive symptoms. We proposed that the assessment of negative symptoms should be routine as part of clinical mental status examination of delusional disorder patients.

Even though categorical diagnoses are useful in psychiatry, some psychotic disorders overlap in genetics, risk factors, clinical presentation, management needs and outcomes.1,2 In this context, a great number of psychiatrists assume that, rather than a group of categories, psychosis is a continuum with different manifestations.3 Hence, different mental disorders conform the so-called schizophrenia or psychosis spectrum, which mainly includes schizophrenia (SCZ), schizoaffective disorder (SCAD) and delusional disorder (DD).

The psychotic continuum also includes some psychotic dimensions. From this perspective, the negative dimension is one of the most replicated factors, and it would be present with varying intensities in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder.4–6 However, there are psychotic disorders, such as DD, where negative symptoms are often overlooked or unrecognized. DD is a mental disorder that has traditionally been considered as a rare psychotic disorder, although current epidemiological studies have indeed demonstrated that its life-time prevalence approaches 0.2%.7 Despite the heterogeneity of symptoms in DD, the predominant psychopathology is based on the delusional ideas, and both classical and current psychopathological descriptions have not incorporated negative symptoms in DD diagnostic criteria.8

The scientific literature has repeatedly shown that patients with DD have a complex symptomatic profile.9,10 However, research on the negative symptoms in DD has been grossly neglected. Thus, most classical authors generally conclude that DD is a monosymptomatic illness.11,12 In contrast, previous studies from our group found evidence that DD patients did indeed exhibit a modest but significant presence of negative symptoms.13 When psychotic symptoms were measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), scores in the negative scale showed that they were present in DD. Furthermore, negative symptoms such as decreased speech fluidity, limited abstract thinking, and emotional coldness expressed high commonalities in the particular factor analysis of PANSS for DD.7 We postulate that should the negative dimension be a valid primary psychotic-symptom dimension, it should express even minimally in a psychotic disorder such as DD where a variety of cognitive,14 affective and schizoid symptoms (apart from just delusions) have been reported to occur. Nevertheless, DD compared to SCZ and SCAD showed significantly less negative and positive symptoms.

Other than Muñoz-Negro et al.,9 few studies have examined negative symptoms across the psychotic spectrum. However, some studies compared in pairs patients with SCZ, SCAD and DD. Their results showed that, compared to patients with SCAD, patients affected by SCZ show a higher level of negative symptoms, but less positive symptomatology.15 And when they compared first episode of DD and SZC, the same level of psychopathology (negative and positive) was exhibited by both groups of patients.16

So far, in spite of all schizophrenic dimensions being present in all three major psychotic disorders, very few studies have explored the negative dimension into different groups of psychotic patients, or specifically in DD patients. For this reason, we studied negative symptoms in a sample of psychotic patients including patients with DD, SCZ and SCAD. Based on previous findings, we expected a multidimensional psychopathological gradient across different categories, with patients with DD exhibiting similar positive symptoms but lesser negative symptoms, compared to those found in patients with SCZ and SCAD. And second, we wanted to demonstrate that negative symptoms are not so rare in DD when compared with positive symptoms.

MethodsParticipantsOne hundred and twelve adults (n=112) attended in different hospitals and community mental health settings from Andalusia (Spain) participated in the study. The sample included 67 patients diagnosed with SCZ, 22 with DD and 23 with SCAD, according to DSM-IV-TR criteria.8 In all cases, participants were outpatients either in a remitting or maintenance stage. And they were also on treatment, including antipsychotic medication. Both, clinical state and compliance, were evaluated by every psychiatrist participating in the study on the basis of a clinical impression. Inclusion criteria were the following: 1. To meet DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for SCZ, DD and SCAD; 2. Being older than 18 years; 3. Patient agreement to participate. Exclusion criteria were the following: 1. Mental retardation; 2. Any type of dementia. All participants received an information sheet containing sufficient information and returned a signed informed consent. The study was performed in accordance with ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the local ethical committees of every participating hospital. In order to assure a good inter-rater reliability, all interviewers participating in this study were trained to use the PANSS by two of the authors (JEMN and IIC), and more than half of the final sample was collected by a single interviewer (JEMN).

MeasuresThe Spanish version of PANSS17 was used to assess psychopathology. PANSS13 is an instrument designed to evaluate positive, negative and general psychopathological symptoms in schizophrenia. It is composed by 30 items, 7 items for the positive scale, 7 items for the negative scale and 16 different items for general psychopathology. Items scoring range in increasing symptoms intensity from 1 to 7. In addition, a composite scale can be calculated to determine the positive or negative subtype of every patient.

Premorbid intelligence quotient (IQ) was calculated using Bilbao-Bilbao and Seisdedos18 formula based on sociodemographic data. This formula uses the sociodemographic variables age, sex, educational level, urbanicity and geographical region to estimate a participant's IQ.

Statistical analysesDescriptive statistics for age, sex, educational level, premorbid IQ, illness duration, and PANSS score were calculated for the three groups of patients. One-way ANOVA or Chi-squared test was performed for age, educational level, premorbid IQ, illness duration, and PANSS positive, negative, general and composite index. When the differences were statistically significant, post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjust were performed. In addition, we carried out t-test between positive and negative PANSS scorings in DD group. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0

ResultsSample characteristicsThe sample was composed of 112 patients. Of them, 22 were in the DD group, 67 in the SCZ group and 23 in the SCAD group. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients.

| Variable | SCZ (n=67) | DD (n=22) | SCAD (n=23) | Statistic | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 40.40 (11.45) | 49.59 (12.62) | 44.35 (13.43) | 6.78 | 0.002* |

| Sex (n, %) | |||||

| Men | 44 (65.7) | 15 (68.2) | 12 (52.2) | 1.61 | 0.44 |

| Women | 23 (34.3) | 7 (31.8.) | 11 (47.8) | ||

| Years of education (n, %) | |||||

| Incomplete primary school | 12 (17.9) | 4 (18.2) | 2 (8.7) | 10.88 | 0.09 |

| Complete primary school | 38 (56.7) | 9 (40.9) | 10 (43.5) | ||

| Higher education | 11 (16.5) | 6 (27.3) | 11 (47.8) | ||

| University | 6 (8.9) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Premorbid IQ (mean, SD) | 109.49 (14.08) | 111.81 (13.50) | 114.52 (10.70) | 1.72 | 0.18 |

| Illness duration (mean years, SD) | 16.6 (10.6) | 13.1 (11.6) | 21.4 (8.3) | 3.56 | 0.032* |

Note: SCZ, schizophrenia; DD, delusional disorder; SCAD, schizoaffective disorder; IQ, intelligence quotient.

There were statistically significant differences between the groups regarding age and illness duration. Mean age was 43.8 years (SD=13.2). Patients with SCZ were significantly younger than those with DD. Male sex was predominant (average 63.3%), reaching 68.2% in patients with SCAD and around 57% for the other groups. As for educational level, the differences did not reach statistical significance, but completed higher studies were more frequent among patients with SCAD whilst complete primary studies were significantly more frequent among SCZ and DD groups. Premorbid Intelligence Quotient (IQ) was not significantly different between the groups, being the mean 110.51 (SD=12.8). Mean illness duration was 16.2 years (SD=10.8), and SCAD group showed a significantly larger duration of illness than DD group.

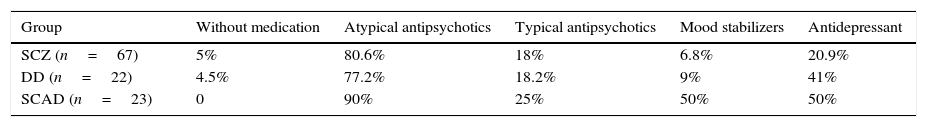

All patients were under antipsychotic medication at the time of testing and had good compliance on the basis of a clinical impression. The majority were receiving atypical antipsychotics and/or anxiolytics and, to a lesser extent, mood stabilizers, antidepressants and/or typical antipsychotics (see Table 2).

Percentage of patients from each group taking different types of medication.

| Group | Without medication | Atypical antipsychotics | Typical antipsychotics | Mood stabilizers | Antidepressant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCZ (n=67) | 5% | 80.6% | 18% | 6.8% | 20.9% |

| DD (n=22) | 4.5% | 77.2% | 18.2% | 9% | 41% |

| SCAD (n=23) | 0 | 90% | 25% | 50% | 50% |

Note: SCZ, schizophrenia; DD, delusional disorder; SCAD, schizoaffective disorder.

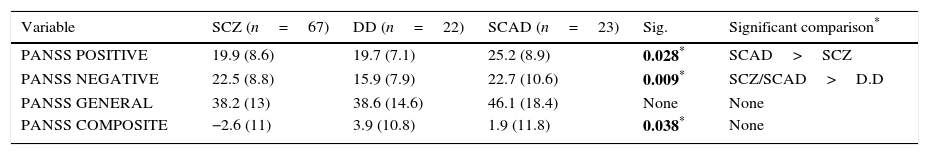

The three clinical groups showed statistically similar Total PANSS scores, (F=2.6, p≥.78). However, they differed in Positive, (F=3.74, p≤.028), Negative (F=4.87, p≤.001), and Composite PANSS scores (F=3.38, p≤.038). Post hoc comparisons indicated that SCAD patients suffered from more severe positive symptoms than SCZ, with DD being as affected as SCZ patients. Negative symptoms were also more severe in SCAD and SCZ patients than in DD (see Table 3).

Mean values (and standard deviations) on the clinical assessment for the three groups of patients.

| Variable | SCZ (n=67) | DD (n=22) | SCAD (n=23) | Sig. | Significant comparison* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS POSITIVE | 19.9 (8.6) | 19.7 (7.1) | 25.2 (8.9) | 0.028* | SCAD>SCZ |

| PANSS NEGATIVE | 22.5 (8.8) | 15.9 (7.9) | 22.7 (10.6) | 0.009* | SCZ/SCAD>D.D |

| PANSS GENERAL | 38.2 (13) | 38.6 (14.6) | 46.1 (18.4) | None | None |

| PANSS COMPOSITE | −2.6 (11) | 3.9 (10.8) | 1.9 (11.8) | 0.038* | None |

Note: SCZ, schizophrenia; DD, delusional disorder; SCAD, schizoaffective disorder.

We performed analyses to compare positive and negative symptomatology in DD group (see Table 3). Independent samples’ t-tests were carried out to compare PANSS positive and PANSS negative subscales, respectively. The result showed no significant differences between positive and negative symptomatology in this group of patients (T=1.67, p≥.11).

DiscussionOur results showed that patients with SCAD suffered from more positive symptoms than patients with SCZ and DD, the latter being less affected by negative symptoms than the groups of patients with SCAD and SCZ. These results clearly showed that negative symptoms do occur in DD if to a modest degree. These findings are also compatible with previous studies that have provided similar dimensions in the delusional disorder.9,10 Such findings could be the result of a minimal expression of a valid primary negative psychotic dimension that would span across all psychoses including DD. Moreover, we could not find significant statistical differences between positive and negative symptoms in DD. Similar results were found by a recent work comparing 71 first episodes of DD and SCZ,16 with a negative PANSS scoring (10.1; SD=4.1), and another work with a bigger sample size of DD.7 Nonetheless, these results contradict the classic definition of DD as a monosymptomatic disease.11,12

The existence of negative symptoms in DD might not only have theoretical consequences such as its inclusion in the psychosis continuum or controversies on its clinical definition. It also raises the concerns about the pharmacological and psychological treatment of patients with DD. Since second-generation antipsychotics are more effective – or at least less harmful – over negative symptoms than first-generation antipsychotics,19 it is necessary to study if second-generation antipsychotics are useful over this kind of symptoms in DD. Further, we need to test the efficacy of different antipsychotics on different symptomatic dimensions occurring in DD. Also, some psychological treatments have demonstrated to be effective on negative symptoms20 and should be considered for inclusion in the treatment plan for patients with DD.

Regarding possible biases when evaluating negative symptoms, it is well known that some antipsychotics side effects can be mistaken for true primary negative symptoms.21 To control for this plausible bias, we accounted for data on treatment in each group (Table 2). The percentage of patients taking antipsychotic medication (both, first-generation and second-generation) in each group was quite similar for DD and SCZ.

For future studies, it would be interesting to have a bigger sample size that enables us to analyze patients with different DD subtypes, given that patients with DD are frequently a heterogeneous group,8 and there can be up to seven types of different DD. Among them, mixed and grandiosity type have shown more negative symptoms.22 Moreover, although PANSS is a validated scale for negative symptoms in SCZ, in future studies, it is suggested to use a more specific and precise instrument to assess negative symptoms specifically such as the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS).23 Psychotic continuum includes a great range of psychotic disorders such as SCZ, SCAD and DD.9 Our results support the notion of the existence of common psychotic dimensions expressed in different intensities across a variety of psychotic categories within a pan-psychotic spectrum.8 With regard to psychopathology, our results suggest such spectrum showing increasing levels of severity from DD to SCAD, with SCZ as an intermediate category.

With regard to the differences found in age and illness duration of the patients composing our sample, we have to emphasize that DD is a middle- or late-onset disease22 compared to SCZ and SCAD. This could explain why our sample patients with DD were older and with a shorter illness duration than those with SCZ and SCAD, particularly compared to the latter.

Finally, we suggest that the assessment of negative symptoms should be a part of clinical mental status examination of patients with DD and propose that DSM-5 psychotic dimensions could be applicable to DD symptomatic profiling.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest.

Funding/supportThe Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) has funded Prof. Jorge Cervilla for the PARAGNOUS and Pheno-Psych studies (PS09/01671 and PI13:01967). Dr. Muñoz-Negro, Miss. Lozano and Prof. Cervilla were also funded partially via CIBERSAM CB07/09/0036. Dr. de Portugal and Prof. Cervilla were also funded by ISCIII for the DELIREMP Study (PI021813).

We thank all participating patients for their acceptance to take part in this study. We also thank their psychiatrists, nurses and medical secretaries for helping us approaching them in the different participating centres. We are very appreciative of the institutional support from UNIPISMA (Unidad de Investigación del Plan Integral de Salud Mental de Andalucía). This study was partially funded through CIBERSAM, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias del Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS, Grant No. PI13/01967).