To evaluate the brochure provided to relatives on admission to Spanish Intensive Care Units (ICU) regarding nursing information.

MethodologyDescriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study from September–December 2019. A total of 280 adult ICUs were included, according to the list of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care. The brochure was requested through personal contact, phone call, twitter, or hospital website.

Analysed variablesHospital (public/private), university (yes/no), visiting (open/closed), medical and nurse information. Descriptive statistics and X2 test (relations nurse information and other variables).

ResultsData were collected from 228 ICU (81.4%), of which 25 (11%) did not have a brochure. A total of 77.8% were public and 49.8% university hospitals. Of the hospitals, 94.1% had closed visiting hours, although 42.4% supplemented it with flexible. All the hospitals included daily medical information with an established timetable, 21.7% (n = 44) contained nurse information, 27.3% with established hours and 38.6% during visits. Of the nursing information, 79.5% referred to care, 29.5% to needs, 13.6% to well-being, 15.9% to the patient's condition, 11.4% to the environment, 9.1% to observations, and 29.5% to clarifications. A total of 17.2% of all ICU offered to collaborate in care. Of the brochures with nurse information, 90.9% were public hospitals and 9.1% were private (p = .02). Of the hospitals, 65.9% were university compared to 34.1% who were not (p = .02).

ConclusionsWhile medical information is consistently reflected in all brochures, only a few contain nursing information with generic and non-homogeneous and specific content. These results contrast with the reality of the ICU, where the nurse is the professional with the greatest contact with the family. The official provision of nursing information occurs more frequently in public and university hospitals. It is necessary to standardise this information, since as a responsible part of the care process, nurses must communicate their care in a formal manner, and thus help make their work visible.

Evaluar la guía de acogida proporcionada a los familiares en las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) españolas respecto a la información enfermera.

MetodologíaEstudio descriptivo, transversal multicéntrico de septiembre-diciembre de 2019. Se incluyeron 280 UCIs de adultos, según listado de la Sociedad Española de Cuidados Intensivos. El folleto se solicitó mediante contacto personal, llamada telefónica, twitter o web del hospital.

Variables analizadasHospital (público/concertado o privado), universitario (sí/no), visita (abierta/cerrada), información médica y enfermera. Estadística descriptiva y prueba Chi cuadrado (relación información enfermera y resto de variables).

ResultadosSe recogieron datos de 228 UCI (81,4%), de las cuales 25 (11%) no disponían de folleto. Un 77,8% eran públicas/concertadas y el 49,8% universitarias. El 94,1% tenían horario cerrado, aunque el 42,4% lo complementaban con uno flexible o de acompañamiento. El 100% incluía información médica diaria con horario establecido. El 21,7% (n = 44) contenía información enfermera, un 27,3% con horario establecido y un 38,6% durante las visitas. El 79,5% la información enfermera hacía referencia a cuidados, 29,5% a necesidades, 13,6% al bienestar, 15,9% al estado del paciente,11,4% al entorno, 9,1% a observaciones y 29,5% a aclaraciones. El 17,2% de todas las UCI ofrecía colaborar en los cuidados. De los folletos con información enfermera, el 90,9% eran hospitales públicos/concertados y el 9,1% privados (p = 0,02). El 65,9% eran universitarios frente el 34,1% que no (p = 0,02).

ConclusionesMientras que la información médica queda reflejada de forma unánime, una baja proporción de folletos citan la información enfermera con un contenido poco homogéneo y concreto. Estos resultados contrastan con la realidad de la UCI, donde la enfermera es el profesional con mayor contacto con la familia. La referencia oficial de la información enfermera se da con más frecuencia en hospitales públicos/concertados y universitarios. Es necesario regularizar dicha información, ya que como parte responsable del proceso asistencial, la enfermera debe comunicar sus cuidados de manera formal, contribuyendo así, a hacer visible su labor.

Spanish ICUs offer a family welcome brochure in which the doctor is identified as the official information provider.

However, only a few of these brochures mention nurse information, which does not reflect reality as nurses have the most complete vision of the patient and the greatest contact with relatives.

Implications of the studyNurse information needs to be standardised and formalised, as overseers of the care process they must inform about their care and thus help make their work visible.

Providing information to patients and families about both medical and nursing activities is a common obligation, especially in the intensive care unit (ICU), where it is often not possible for it to be given directly to the patient due to their critical condition. Admission to ICU causes anxiety, depression, and a high percentage of relatives show symptoms of post-traumatic stress,1–4 which can make the information provided by professionals difficult to communicate and understand, given their emotional state. There are many initiatives that have shown that giving the family a welcome booklet or brochure on admission helps reduce their stress.5,6

The family's need for information throughout the patient’s stay in ICU, is directly associated with family satisfaction with the care received.7,8 In the study conducted by Velasco et al.9 on the main information demands, relatives expect medical professionals to inform them about diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, but they also identify the nurse as the provider of information on care, environment, and the rules of the unit. However, and according to the study by Valls-Matarín et al.10 conducted in various Catalan hospitals on family satisfaction with nurse information, it is precisely on the abovementioned concepts, the offer of spiritual help and information on the care that relatives can provide during their visit, where relatives reported a lack of information and nurses reported providing less information. In fact, in Spanish ICUs it is usually the doctor who is the official information provider, and often the nurse is absent from the information process, or even refuses to communicate with relatives.11

In 2017 the SEEIUC and Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units published recommendations on welcoming relatives in ICUs, recommending leaflets or brochures to include various points, with both medical and nursing information.12

The study hypothesis was that less than half of Spanish ICUs included nursing information in their brochures, therefore the aim of this study was to evaluate the welcome brochure provided to relatives in Spanish ICUs in terms of nursing information.

MethodologyA descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study was designed and conducted between September 2019 and February 2020. A total of 280 adult ICUs were included, according to the list of the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units and the SEEIUC. The leaflet or welcome brochure for each unit was requested by personal contact, telephone call, Twitter, or direct consultation through the hospital's website.

The following variables were collected: type of hospital (public/trust or private), university (yes/no), medical and nursing information, family visits (open 24 h/closed, or with time restrictions), and family collaboration in basic care.

Sample calculationThere is an available target population of Spain’s 280 ICUs. It is estimated that 50% of the ICUs refer to nurse information in their leaflet. Assuming a margin of error of 5% with a confidence level of 95%, a sample of 169 ICUs is required.

Descriptive statistics with absolute and relative values. The χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used to determine the relationship between nurse information, university hospital, and the centre’s tenure. The level of statistical significance was set at p < .05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® version 19 for Windows®.

ResultsData were obtained from 228 Spanish ICUs, representing 81.4% of the total sample. A total of 35.1% of the brochures were provided by personal contact, 37.3% by telephone call, 21.9% by direct consultation through the hospital website, and the remaining 5.7% via Twitter.

Of the ICUs studied, 89% (n = 203) had a welcome brochure, while the remaining 25 (11%) offered information about the service verbally or by means of posters located in the unit itself.

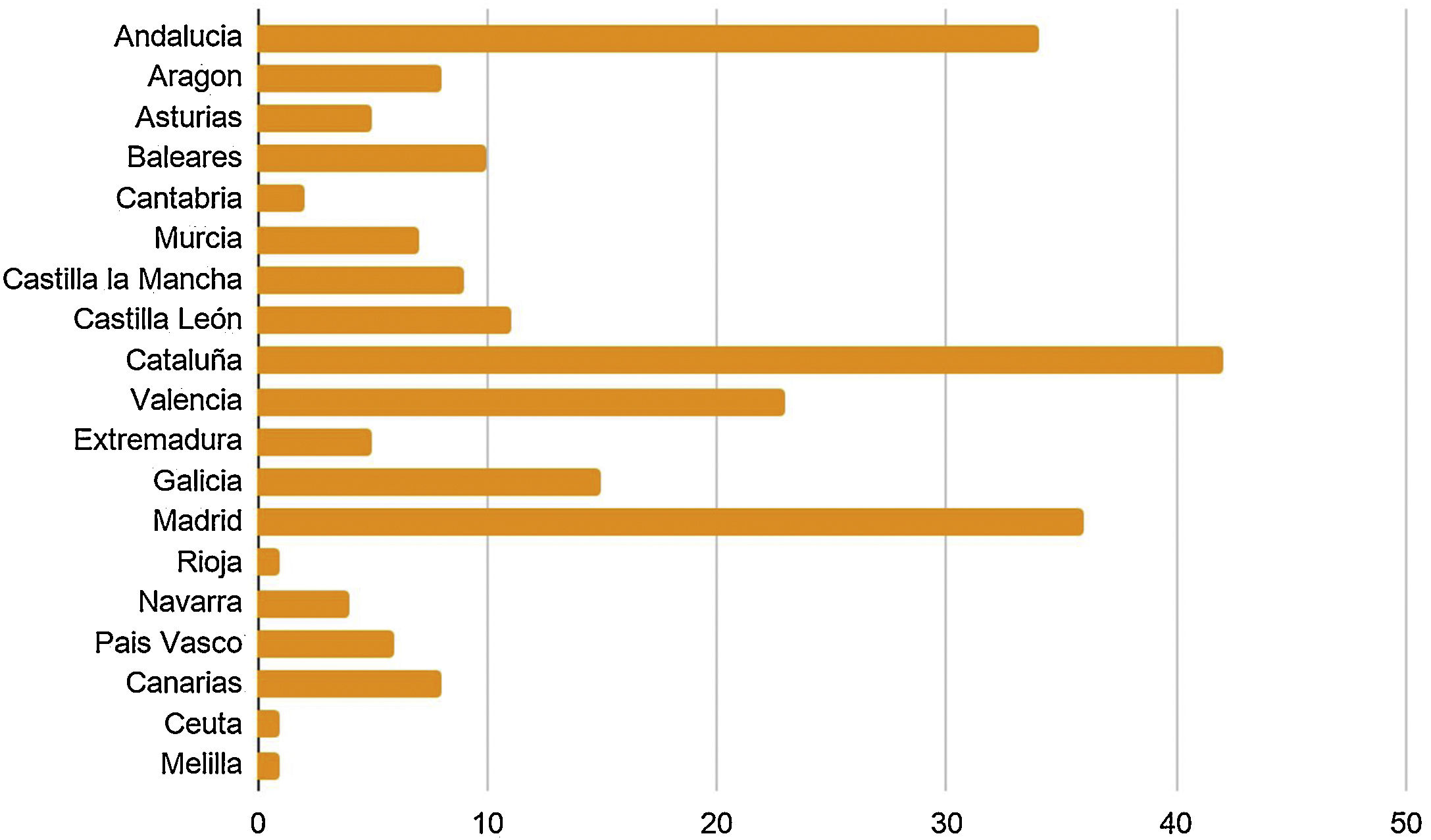

The distribution according to each autonomous community are shown in Fig. 1.

Nursing information was included in 21.7% of the welcome brochures (Table 1) and the content of this information is shown in Table 2, care being the element most frequently mentioned. Of the brochures, 34.1% did not mention information times, 27.3% specified a time, and in 38.6% information was given during visiting hours.

Variables analysed from the welcome brochure (n = 203).

| Variables | ICU, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hospital type | |

| Public/trust | 153 (75.4) |

| University | 105 (51.8) |

| Health information | |

| Medical information | 203 (100) |

| Nurse information | 44 (21.7) |

| Visiting times | |

| Open visiting | 8 (3.9) |

| Restricted visiting | 195 (96.1) |

| Accompaniment visiting | 86 (42.4) |

Content of nurse information in the welcome brochures of Spanish ICUs (n = 44).

| Nurse information in relation to: | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Care | 35 (79.5) |

| Patient wellbeing | 6 (13.6) |

| Patient needs | 13 (29.5) |

| Patient’s condition | 7 (15.9) |

| Unit environment | 5 (11.4) |

| Clarifications to the family | 13 (29.5) |

| Nursing observations | 4 (9.1) |

Of the ICUs providing nurse information, 90.9% belonged to public/trust hospitals and the remaining 9.1% to private hospitals (p = .02), and 65.9% were university hospitals compared to 34.1% that were not (p = .02).

Medical information appeared in 100% of the brochures, 99% specified daily information and 97.5% indicated times. In 47.3% information was provided on admission to the unit, in 69.5% information was provided if there was a significant change in the patient's condition, and in 21.7% information was provided outside the established times at the request of relatives.

In 3% (n = 6) of the brochures, information was provided to the family member jointly by doctors and nurses.

Regarding visiting, in 96.1% of the ICUs there was some type of restriction, although in 42.4% of them it was extended to be more flexible or for accompaniment. Collaboration in patient care was proposed in 17.2%.

DiscussionFew Spanish ICUs include nursing information in their welcome brochures for relatives, unlike medical information, which is unanimously referenced in all the brochures studied. This would suggest that nursing information continues to be given informally, with little recognition from the institutions. Although nurses are increasingly better trained and assume more responsibilities, their role as formal information givers is limited, perhaps because we continue to be anchored in a biomedical model that considers doctors the highest authority13,14 and makes them responsible for giving information.15 There may be many reasons for this lack of participation, such as nurses protecting themselves from the emotional stress involved in communicating with family members,16 or because nurses are often unaware of the information given by the doctor. In fact, the inclusion of joint doctor-nurse information in brochures is merely anecdotal and similar to other studies also conducted in Spanish ICUs using surveys of department heads15,17 to establish how health information is provided.

However, nurses, as part of the care process, are also responsible for outcomes and, therefore, must report everything concerning their competence, as indicated in their code of ethics.18 However, despite their being recognised by relatives as professionals who provide information,9 there are studies in which 50% of relatives stated that they had not received information from nurses, and if they had, it was at the discretion of the nurse.10,11

The brochures that mention nurse information give the aspects on which they can give information, some of which were as abstract as “observations” or “clarifications”. Perhaps these terms are due to a lack of knowledge of nursing competencies to provide information and because there is little tradition for nurses to inform about the care they provide.10

Medical information was protocolised for fixed times and a quarter of the ICUs also offered the possibility of relatives receiving medical information on demand, which suggests a certain degree of openness in this respect, since "on demand" implies recognition of the relatives' need for information and motivation on the part of the medical staff to meet it.19 However, only a few ICUs had times reserved for nurse information, possibly due to their continuous presence at the bedside, even during visiting hours.

In this regard, and despite the fact that only 4% of the ICUs announced an open-door policy without any type of visiting restriction for relatives, as in other countries,20,21 almost half the brochures offered extended visiting or for accompaniment, often defined as open-door ICUs in the literature, suggesting that we are immersed in a period of change in Spain. This, and the nurse’s continuous presence with patients, generates more opportunities for interaction between the nurse and the family, necessitating a paradigm to show and give guidance on the information that falls to nurses and how they can provide it in an organised and understandable way. Likewise, nursing universities should be promoters of this information, and provide tools that facilitate this activity for new generations, because humanisation of ICU22–24 inevitably involves nurses.

For some years now, the involvement of the family in ICUs has been encouraged, meaning that they can, for example, participate in basic care.15 This aspect, which was only reflected in very few of the brochures studied, is an area where relatives most demands,9,25 and is usually undertaken by nurses, and therefore communication with the family is again essential. Rodríguez Martínez et al.26 demonstrated, in a study conducted in an Andalusian ICU that involves relatives in basic care such as feeding, mobilisation, and hygiene, reduced their levels of anxiety and provided greater information and accompaniment time.

The fact that nursing information is better represented in brochures provided in public/trust hospitals than in private hospitals may be because nurses are generally not included in the service portfolio of private hospitals or, in other words, patients usually go to the hospital through direct contact with a specific doctor, which qualifies them as the main interlocutor. University hospitals could also be more reflective of nurse information because of their links with to the nursing faculty.

An article27 published on global nursing issues in 2015 concluded a need to enhance the visibility of nurses. Currently there are initiatives, such as the global Nursing Now campaign, where work is being done to increase the status of nurses and strengthen their leadership in health policy. To do this, the community needs to be aware of their role and therefore nurses need to provide information about the work they do. Given that providing an information brochure on admission to ICU seems to be generalised and consolidated practice in Spain, in almost 90% of ICUs, as in other European countries,20,28 reflecting nurse information in the brochure could help formalise it, promote it, and in turn encourage families to demand this information.

The recognition or social visibility demanded for nurses requires their greater involvement in information, because what we do not know cannot be recognised.

ConclusionsA small proportion of Spanish ICUs offer welcome brochures that mention nursing information, this result is in line with the proposed hypothesis. The content of this information is not very homogeneous or precise. These results contrast with reality, where the nurse has the greatest contact with relatives and the most complete vision of the patient. It is necessary to regularise and protocolise this information, and train nurses in effective communication, since as overseers of the care process they must formally communicate their care, and thus make their work more visible.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To all those who anonymously and from their place of work: nurses, care assistants, doctors, salespeople, union members, supervisors, friends, and acquaintances who helped us and contributed to making this project possible.