To identify risk factors for Oxygen (O2) needs in pregnant and postpartum women with COVID-19.

MethodsProspective cohort involving pregnant women hospitalized with COVID-19 from April to October 2020. The oxygen need was analyzed regarding risk factors: demographic characteristics, clinical and laboratory parameters at hospital admission, and chest Computer Tomography (CT) findings. Poisson univariate analysis was used to estimate the Relative Risk (RR) and 95% Confidence Intervals.

Results145 patients, 80 who used and 65 who did not use O2, were included. Body mass index ≥ 30, smoking, and chronic hypertension increased the risk of O2 need by 1.86 (95% CI 1.10–3.21), 1.57 (95% CI 1.16‒2.12), and 1.46 (95% CI 1.09‒1.95), respectively. Patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19 and for obstetric reasons had 8.24 (95% CI 2.8‒24.29) and 3.44 (95% CI 1.05‒11.31) times more use of O2 than those admitted for childbirth and abortion. Respiratory rate ≥ 24 breaths/min and O2 saturation < 95% presented RR for O2 requirements of 2.55 (1.82‒3.56) and 1.68 (95% CI 1.27–2.20), respectively. Ground Glass (GG) < 50% and with GG ≥ 50%, the risk of O2 use were respectively 3.41-fold and 5.33-fold higher than in patients who haven't viral pneumonia on CT. The combination of C-reactive protein ≥ 21 mg/L, hemoglobin < 11.0 g/dL, and lymphopenia < 1500 mm3 on hospital admission increased the risk of O2 use by 4.97-times.

ConclusionsIn obstetric patients, clinical history, laboratory, clinical and radiological parameters at admission were identified as a risk for O2 need, selecting the population with the greatest chance of worsening.

Since the World Health Organization declared the new SARS-CoV-2 pandemic installed in March 2020, an avalanche of knowledge and discoveries has hit us. Many protocol changes have occurred, including the identification of pregnant women as a risk group for progression to severe forms of the disease and, therefore, at greater risk of needing oxygen support and Orotracheal Intubation (OTI).1-3

Developing countries, which already had difficulties in reducing maternal death and near-miss rates, quickly faced an increase in maternal death from COVID-19. In this context, Brazil has surpassed 1,800 cases of maternal death due to COVID during the pandemic.4 This increase in maternal mortality has been pointed out by studies that reinforce socioeconomic inequalities and the difficulty in structuring the health system to care for severe cases of diseases in pregnant and postpartum women.4-6

The identification of patients at greater risk of clinical deterioration has been investigated, especially in the general population.7 Several studies propose risk factors for admission to the Intensive Care Units (ICU), orotracheal intubation, and death.8-10 Regarding the pathophysiology of COVID-19, it is known that the need to use O2 can be considered a sentinel event since from this evolution there is a risk of worsening the respiratory condition, often quickly.11-12

Being able to screen pregnant women at higher risk of O2, use would prioritize care for the maternal-fetal binomial and, mainly, greater access to ICU and OTI. Thus, considering that the clinical deterioration of the disease most often implies the onset of severe acute respiratory syndrome, requiring oxygen support,11,12 this study aims to identify the risk factors for the need for oxygen during hospitalization of pregnant postpartum women with COVID-19.

Materials and methodsThe data analyzed in this study are part of the cohort study “Exploratory study on COVID-19 in pregnancy” Data were selected concerning pregnant and postpartum women hospitalized at Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo with COVID-19 (with flu-like symptoms or severe acute respiratory syndrome) confirmed by positive laboratory SARS-CoV-2 test, from April to October 2020.

The use of O2 during pregnancy was indicated to ensure the following clinical parameters: O2 saturation greater than or equal to 95% (if postpartum, greater than or equal to 92%), a respiratory rate between 20 and 24, the avoidance of hypercapnia (pCO2 > 45 mmHg) during assisted ventilation, correction and treatment of respiratory effort and the support of cardiovascular stability. To ensure these parameters, the supply of O2 occurs progressively, and when the maximum supply of each device is reached, it passes on to the next. It starts with a nasal catheter (gradually increasing to a maximum flow of 6 liters/minute) and progresses respectively to a face mask (maximum of 15 liters/minute with FiO2 at 50%), a high-flow nasal cannula (maximum 40 to 70 liters/minute), non-invasive ventilation, and finally orotracheal intubation.11,12

Indications for admission to the intensive care unit included: O2 saturation < 95% despite O2 catheter at 6 liters/minute, ventilatory effort despite O2 supply, PaO2/FiO2 ratio (partial pressure of arterial O2/inspired O2 fraction) < 300, arterial hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg), altered peripheral perfusion, altered level of consciousness and renal dysfunction.11,12

For the analysis, two groups were compared, one with O2 need and the other without O2 concerning the following factors:

- •

Demographic: maternal age, body mass index at admission, smoking.

- •

Clinical: blood type (divided into type O and not O),13 pre-existing maternal comorbidities (chronic arterial hypertension, pneumopathy, cardiopathy, diabetes, rheumatologic diseases, and neurological diseases).

- •

Obstetric history: pregnant woman, postpartum woman, presence of pre-eclampsia and/or gestational diabetes in this pregnancy.

- •

Reason for hospitalization: admission due to delivery or abortion, when the patient was admitted to labor and delivery or abortion but had mild symptoms of COVID; hospitalization due to COVID-19, when symptoms of COVID-19 indicated hospitalization; and admission for other reasons, which included patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized for reasons related to pregnancy (premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, diabetes, etc.).

- •

Factors related to COVID-19: gestational age at onset of symptoms, days since onset of symptoms at hospital admission, types of symptoms (were considered a fever, cough, odynophagia, myalgia, asthenia, runny nose, diarrhea, anosmia, dysgeusia, dyspnea, headache, and fatigue).

- •

Clinical parameters on admission: heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and oxygen saturation.

- •

Laboratory parameters on admission: hemoglobin, leukocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, platelets, C-Reactive Protein (CPR), aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, lactic dehydrogenase, creatine phosphokinase, D-dimer, troponin, creatine and urea. Parameters that proved to be significant in a continuous analysis were further analyzed in a combined and stratified way into cut-off levels. For the evaluation of CPR and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, tertiles of distribution of values in the studied sample were determined.

- •

Chest Computed Tomography (CT) findings were considered not suggestive of COVID-19 when normal or in the presence of consolidation or pleural effusion, and suggestive of COVID-19 in the presence of Ground Glass (GG) image and classified as GG < 50% and GG ≥ 50%. CT was indicated on the admission of all patients with flu-like symptoms and positive COVID, as part of the care protocol, regardless of the need for O2 supply.

- •

Disease evolution: intensive care unit admission, days of hospitalization.

An analysis of the type of oxygen support and the risk of orotracheal intubation was also performed, considering the number of days of O2 usage, the use of O2 on hospital admission, and the use of an O2 catheter, the use of face mask, and high-flow nasal cannula.

The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Hospital das Clínicas (CAAE: 30270820.3.0000.0068, approved in April 11th, 2020). Each patient added to the data analysis was included after registration in CAAE After receiving information and reading, all participants signed the consent form.

Statistical analysisThe quantitative variables were expressed as mean (standard deviations) and medians (interquartile range) values, and the categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Poisson univariate analysis with a log link function and robust variance was performed to estimate the relative risk of O2 use (RR) and their respective 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). The Wald test for statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05) was used.14 SPSS version 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statics for Windows, version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for data analysis.

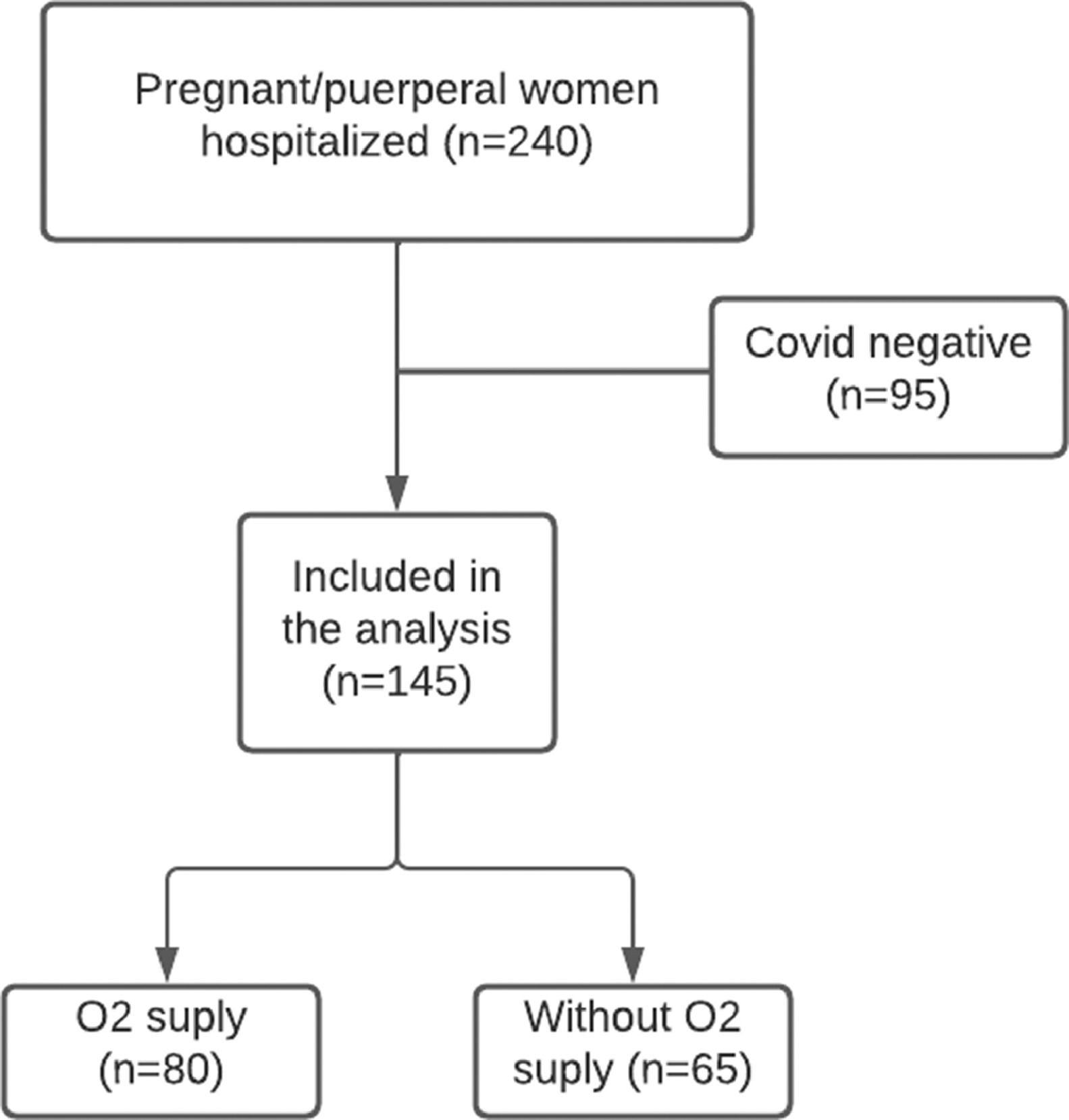

ResultsDuring the study period from April to October 2020, 240 pregnant/puerperal women with suspected COVID-19 were hospitalized. Of these, 95 tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, leaving 145 patients (144 pregnant women and 1 postpartum woman) included for analysis: 80 who used oxygen and 65 who did not (Fig. 1). The ICU admission rate was 33.1% (n = 48) and the maternal mortality rate was 4.1% (n = 6). That 80 (55.2%) patients who received oxygen during hospitalization, 41.4% (n = 60) were already hospitalized receiving O2, and the mean time of O2 use was 7.5 days (5‒15 days). The types of O2 supplementation used were: O2 catheter in 47.6% (n = 69), face mask in 29% (n = 42), high-flow nasal cannula in 11% (n = 16) and IOT in 20% (n = 29).

Clinical risk factors for the use of O2 were shown (Table 1): higher average maternal age (31.5 ± 6.5 vs. 27.7 ± 7.4 RR = 1.03; 95% CI 1.01‒1.05); BMI ≥ 30 (1.86; 95% CI 1.10‒3.21); smoking (1.57; 95% CI 1.16‒2.12) and chronic hypertension (1.46; 95% CI 1.09‒1.95).

Comparison of demographic, clinical, and obstetrical characteristics between the COVID-19 patients who did not use O2 with those who used O2 during hospital admission.

| Characteristics | O2 use (n = 80) | No O2 use (n = 65) | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Maternal age, yearsa | 31.5 (6.5) | 27.7 (7.4) | 1.03 (1.01‒1.05) |

| Body mass indexb | 32.1 (28.71‒37.32) | 28.7 (25.08‒31.23) | 1.04 (1.02‒1.06) |

| < 25 | 9 (11.2) | 16 (24.6) | Reference |

| ≥ 25 < 30 | 18 (22.5) | 23 (35.4) | 1.22 (0.65–2.28) |

| ≥30 | 53 (66.2) | 26 (40.0) | 1.86 (1.10–3.21) |

| Smoking habit (n = 144) | 10 (12.5) | 2 (3.1) | 1.57 (1.16‒2.12) |

| Blood Type (n = 142) | |||

| O type | 32 (41.0) | 29 (45.3) | 0.92 (0.68‒1.25) |

| Other types | 46 (59.0) | 35 (54.7) | |

| Pre-pregnancy comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 18 (22.5) | 6 (9.2) | 1.46 (1.09‒1.95) |

| Pneumopathy | 8 (10.0) | 11 (16.9) | 0.74 (0.43‒1.27) |

| Cardiopathy | 5 (6.3) | 3 (4.6) | 1.14 (0.65‒1.99) |

| Diabetes | 4 (5.0) | 3 (4.6) | 1.04 (0.54‒2.00) |

| Otherc | 2 (2.5) | 4 (6.2) | 0.59 (0.19‒1.86) |

| Obstetrical history | |||

| Patient type | |||

| Puerperal | 5 (6.3) | 6 (9.2) | 0.81 (0.42‒1.58) |

| Pregnant | 75 (93.8) | 59 (90.8) | |

| Preeclampsia | 6 (7.5) | 4 (6.2) | 1.09 (0.64‒1.86) |

| Gestational diabetes | 21 (26.3) | 13 (20) | 1.16 (0.85‒1.59) |

Data presented as number (%),

Patients whose reason for hospitalization was COVID-19 and those who were admitted for obstetric reasons received, respectively, 8.24 (95% CI 2.8‒24.29), and 3.44 (95% CI 1.05‒11.31) times more O2 in comparison to patients whose reason was admission for delivery (Table 2). The symptoms of COVID-19 with the highest risk of needing O2 were dyspnea (4.59; 95% CI 2.41‒8.75), cough (3.70; 95% CI 1.87‒7.32), fever (2.20; 95% CI 1.48‒3.27), asthenia (1.86; 95% CI 1.45‒2.37), fatigue (1.79; 95% CI 1.40‒2.30) and odynophagia (1.39; 95% CI 1.03‒1.88). Symptoms of anosmia (0.68; 95% CI 0.49‒0.94) and coryza (0.69; 0.49‒0.99) were associated with a lower need for O2 use. The risk of admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (Table 2) was 2.73 times higher in those who used O2 (57.5%×3%; 95% CI 2.07‒3.61). Two patients who did not require O2 were referred to the ICU: one had supraventricular tachycardia requiring drug cardioversion and the other had a hypertensive crisis refractory to the nitroglycerin use.

Comparison of the reasons for hospitalization and the COVID-19 related aspects between COVID-19 patients who did not need O2 with those who needed O2 at hospital admission.

| O2 use (n = 80) | No O2 use (n = 65) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for hospitalization | |||

| Hospital admission due to delivery and abortion | 3 (3.8) | 28 (43.1) | Reference |

| Hospital admission due to obstetric reasons | 10 (12.5) | 20 (30.8) | 3.44 (1.05‒11.31) |

| Hospital admission due to COVID-19 | 67 (83.8) | 17 (26.2) | 8.24 (2.8‒24.29) |

| COVID-19 | |||

| Gestational age at onset of symptoms, weeks (n = 144) b | 30.42 (25.14‒33.00) | 33.57 (27.43‒37.71) | 1.01 (1.00‒1.01) |

| Days of symptoms at admission (n = 143) b | 8 (5‒10) | 5 (4‒8) | 1.02 (0.99‒1.05) |

| Symptoms | |||

| Fever | 61 (76.3) | 25 (38.5) | 2.20 (1.48‒3.27) |

| Cough | 73 (91.3) | 34 (52.3) | 3.70 (1.87‒7.32) |

| Odinophagy | 18 (22.5) | 7 (10.8) | 1.39 (1.03‒1.88) |

| Myalgia | 44 (55.0) | 26 (40.0) | 1.31 (0.97‒1.76) |

| Asthenia | 29 (36.3) | 5 (7.7) | 1.86 (1.45‒2.37) |

| Coryza | 22 (27.5) | 29 (44.6) | 0.69 (0.49‒0.99) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (5.0) | 3 (4.6) | 1.04 (0.54‒2.01) |

| Anosmia | 28 (35.0) | 36 (55.4) | 0.68 (0.49‒0.94) |

| Dysgeusia | 21 (26.3) | 24 (36.9) | 0.78 (0.56‒1.13) |

| Dyspnoea | 72 (90.0) | 24 (36.9) | 4.59 (2.41‒8.75) |

| Headache | 29 (36.3) | 28 (43.1) | 0.88 (0.64‒1.19) |

| Fatigue | 27(33.8) | 5 (7.7) | 1.79 (1.40‒2.30) |

| ICU admission | 46 (57.5) | 2 (3.1) | 2.73 (2.07‒3.61) |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 9 (7‒18) | 4 (3‒7) | 1.01 (1.00‒1.01) |

Data presented as number (%),

amean (standard deviation) or

Table 3 (clinical and tomographic parameters on hospital admission) shows that respiratory rate greater than or equal to 24 breaths per minute and O2 saturation less than 95% presented relative risks for O2 requirement of 2.55 (95% CI 1.82‒3.56) and 1.68 (95% CI 1.27‒2.20), respectively; CT findings with ground glass < 50% and ground glass ≥ 50% with risks of needing O2 respectively of 3.41 (95% CI 1.21‒9.60) and 5.33 (95% CI 1.92‒14.79).

Comparison of clinical and chest tomography parameters at hospital admission between the COVID-19 patients who did not need O2 with those who needed O2 at hospital admission.

| O2 use (n = 80) | No O2 use (n = 65) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical evaluation on admission | |||

| Heart ratea | 96.5 (16.8) | 92.1 (14.6) | 1.01 (0.99‒1.02) |

| Respiratory rateb | 26 (21‒32) | 20 (18‒22) | 1.03 (1.02‒1.05) |

| < 24 | 26 (32.9) | 54 (83.1) | Reference |

| ≥ 24 | 53 (67.1) | 11(16.9) | 2.55 (1.82‒3.56) |

| Systolic blood pressureb | 117 (106‒130) | 117 (110‒122) | 1.00 (0.99‒1.01) |

| Dyastolic blood pressureb | 71 (69‒81) | 70 (66‒80) | 1.00 (0.99‒1.01) |

| Body temperatureb | 36.4 (36‒36.5) | 36 (36‒36.5) | 1.28 (0.96‒1.72) |

| O2 Saturationb | 96 (95‒98) | 98 (98‒99) | 0.98 (0.97‒0.99) |

| ≥ 95 | 72 (90) | 64 (98.5) | Reference |

| < 95 | 8 (10) | 1 (1.5) | 1.68 (1.27–2.20) |

| Computer Tomography (n = 116) | |||

| Not COVIDc | 3 (3.9) | 13 (32.5) | Reference |

| Ground Glass < 50% | 48 (63.2) | 27 (67.5) | 3.41 (1.21‒9.60) |

| Ground Glass ≥ 50% | 25 (32.9) | 0 (0) | 5.33 (1.92‒14.79) |

Data presented as number (%),

Regarding laboratory tests (Table 4), there was a higher risk of needing oxygen for values of: hemoglobin < 11 mg/dL (1.38; 95% CI 1.04–1.82); lymphocytes < 1.50 mil/mm3 (1.75; 95% CI 1.11–2.75) or less than < 1.00 mil/mm3 (1.98; 95% CI 1.27–3.07); C-Reactive Protein (CPR) levels between 21 to 66.6 mg/L (2.28; 95% CI 1.33–3.91) and CRP > 66.6 mg/L (2.78; 95% CI 1.67–4.62). The association of CRP > 21 mg/L, hemoglobin < 11 g/d/L and Lymphocytes < 1500 mm3 had an RR of 4.97 (95% CI 1.74–14.14) for the O2 need (Table 5).

Comparison of laboratorial parameters at hospital admission between the COVID-19 patients who did not need O2 with those who needed O2 during hospital admission.

| Laboratorial evaluation on admission | O2 use (n = 80) | No O2 use (n = 65) | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (n = 143)b g/dL | 11.0 (10.0‒12.0) | 12.0 (10.0‒13.0) | 0.88 (0.81‒0.97) |

| ≥ 11 g/dL | 46 (57.5) | 47 (74.6) | Reference |

| < 11 g/dL | 34 (42.5) | 16 (25.4) | 1.38 (1.04–1.82) |

| Leukocytes (n = 143)b mil/mm3 | 8.42 (6.21‒10.82) | 9.82 (6.33‒13.03) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| Lymphocytes (n = 143)b mil/mm3 | 1.09 (0.785‒1.425) | 1.36 (1.05‒1.88) | 0.99 (0.99‒1.00) |

| ≥ 1.50 mil/mm3 | 16 (20) | 30 (46.2) | Reference |

| < 1.50 mil/mm3 | 31 (38.8) | 20 (30.8) | 1.75 (1.11–2.75) |

| < 1.00 mil/mm3 | 33 (41.2) | 15 (23.1) | 1.98 (1.27–3.07) |

| Neutrophils (n = 143)b mil/mm3 | 6.870 (4.410‒9035) | 7.250 (4.790‒10.670) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| Neutrophils/Lymphocytes (n = 143)b | 5.9 (3.82‒9.30) | 5.0 (2.93‒6.71) | 1.03 (1.01‒1.05) |

| < 4 | 24 (30) | 24(38.1) | Reference |

| ≥ 4 ≤ 6.8 | 23 (28.7) | 24(28.1) | 0.98 (0.65–1.47) |

| > 6.8 | 33 (41.2) | 15 (23.8) | 1.38 (0.98–1.93) |

| Platelets (n = 143)b mil/mm3 | 224 (187.5‒268) | 220 (155‒275) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| CRP (n = 138) mg/L b | 66.0 (32.0‒116.0) | 18.3 (7.1‒44.0) | 1.005 (1.003‒1.007) |

| < 21 mg/L | 12 (15) | 33 (50.8) | Reference |

| ≥ 21 ≤ 66.6 mg/L | 28 (35) | 18 (27.7) | 2.28 (1.33–3.91) |

| > 66.6 mg/L | 40 (50) | 14 (21.5) | 2.78 (1.67–4.62) |

| AST (n = 141) U/Lb | 25 (19‒38) | 19 (15‒27) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| ALT (n = 141) U/Lb | 18 (13‒26) | 15 (10‒22) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| LDH (n = 129) U/Lb | 260 (197‒326) | 200 (170‒251) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| CPK (n = 120) U/Lb | 51 (30‒97) | 57 (29‒87) | 1.00 (0.99‒1.00) |

| D Dimer (n = 132) ng/mL b | 1.199 (936‒1821) | 1.675 (990‒2.316) | 1.00 (1.00‒1.00) |

| Troponin (n = 120) ng/mL b | 0.005 (0.004‒0.007) | 0.005 (0.004‒0.007) | 1.16 (0.81‒1.65)ⱡ |

| Creatinine (n = 140) mg/dLb | 0.52 (0.44‒0.61) | 0.56 (0.48‒0.63) | 0.64 (0.33‒1.24) |

| Urea (n = 141) mg/dLb | 13 (11‒19) | 16 (13‒19) | 0.99 (0.97‒1.01) |

Data presented as number (%)

a mean (standard deviation) or

Risk estimates for oxygen use with combined laboratory parameters.

RR, Relative Risk; CI, Confidential Interval; CRP, C-Reactive Protein; Ly, Lymphocyte; Hb, Hemoglobin.

All types of O2 use were associated with the need for orotracheal intubation. The use of an O2 catheter had a RR of 2.89 (95% CI 1.37‒6.09); the use of a face mask had a RR of 6.44 (95% CI 3.09‒13.37) and the use of a high-flow nasal cannula, RR of 4.24 (95% CI 2.42‒7.45).

DiscussionPrincipal findingsThe need for O2 in pregnant and postpartum women with COVID-19 is associated with clinical factors (advanced age, obesity, hypertension, smoking), symptoms (dyspnea, cough, fever, asthenia, fatigue, and odynophagia), physical and laboratory examination and tests of images on admission (respiratory rate ≥ to 24 breaths per minute, O2 saturation < 95%, ground-glass CT, hemoglobin values < 11 mg/dL, lymphocytes < 1.50 mil/mm3 and C-Reactive Protein [CPR] levels > 21 mg/L). Furthermore, the combination of CRP ≥ 21 mg/L with hemoglobin < 11.0 g/dL and lymphopenia < 1500 mm3 increased the risk of supplemental O2 almost fivefold. The authors studied the two most frequent obstetric pathologies, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes, and the presence of neither pathologies was shown to be a risk factor for the use of O2, although pregnant women with COVID-19 hospitalized for obstetric complications are at greater risk of using oxygen than those admitted for delivery and abortion. The results also show that the risk of orotracheal intubation can also be estimated and increases as measures of oxygen supplementation progress.

Comparison with results of previous studiesSince the first case reports of COVID-19 in non-pregnant women, overweight has been appointed as an important risk factor for clinical deterioration. Studies in pregnant women have confirmed that, as demonstrated in the present study.9,15-18 It is observed that pre-existing chronic arterial hypertension was a risk factor for the use of oxygen, but few studies on pregnant women corroborate the present findings.17 This difference may be due to the high prevalence of chronic arterial hypertension in the studied population. Among those with pneumopathy, the authors had 19 patients in the entire sample, of which 8 (10%) needed O2 and 11 (16.9%) did not. Although numerically the patients with pneumopathy required less O2 supplementation, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups. This might have been because most of these 19 patients had only mild asthma as their underlying lung disease. Although most studies show lung disease as a risk factor for the clinical worsening of COVID-19.15,17,18 the present findings have already been seen by La Verde et al.,9 who did not find asthma as a risk factor. for aggravation of pregnant women.

The present results are in agreement with the findings of Hessami et al.,15 who point to older maternal age as a risk factor for clinical worsening in pregnant women. In general population studies, blood type O has already been appointed as a protective factor for the unfavorable evolution of COVID-19.13 However, such evidence was found neither in the sample nor in a study by Latz et al.19 The median gestational age at the onset of symptoms was 30,42 weeks in the group that required O2 and 33.57 weeks in the group that did not use O2, but with no statistically significant difference. Although there is consensus in the literature that uterine volume is a mechanical factor that interferes with ventilation, this was not what the authors observed in the present study.

An interesting finding of this study was that pregnant women with COVID-19 who are hospitalized for obstetric indications, even with mild symptoms, have a 3.44 times greater chance of O2 need than those admitted for delivery or abortion. This may suggest that the inflammatory state, present in some complications of pregnancy, may contribute to the worsening of COVID-19. It is important to note that among the patients hospitalized for delivery or abortion, none of these pregnancies was interrupted by the worsening of COVID-19.

The type of symptom that also determines the worsening of COVID-19 in pregnant women has been little studied. Savasi et al.16 observed that fever and dyspnea were associated with more severe clinical conditions. Furthermore, in the present study, it was also observed that cough, asthenia, and fatigue were associated with a higher risk of oxygen use. These symptoms point to a systemic involvement, while anosmia and coryza, which are symptoms more suggestive of upper airway involvement, were associated with a lower risk of oxygen use.

In the present study, increased respiratory rate and low O2 saturation at hospital admission were associated with a greater chance of requiring oxygen. Similar results were observed in an Italian cohort study,16 in which the authors also observed an increase in maternal heart rate as a risk factor, but this fact was not observed in the present series.

In agreement with studies, the following laboratory alterations were observed as a risk factors for oxygen use: decreased hemoglobin rate, lymphopenia, increased neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, and higher levels of C-reactive protein.20-23 Other predictors of clinical worsening in patients with COVID-19 in non-pregnant population cohorts, such as increased DHL, increased D-dimer, and increased creatinine, were not observed in the present study.20-25

As in non-pregnant women, the presence of ground glass findings on chest CT is a relevant predictor of the need to use O2, and the risk increases according to the percentage of involvement of the lung parenchyma.26

All pregnant women who required O2 supplementation had a higher risk of orotracheal intubation. The simple use of an O2 catheter implies an approximately three times greater risk of orotracheal intubation, demonstrating the need for greater surveillance of these patients.

Clinical implicationsIt is known that pregnant women are at higher risk for severe COVID-19 compared to the general population, especially with regard to admission to intensive unit care and the need for orotracheal intubation.1 However, it is difficult to identify pregnant and postpartum women who will develop a severe respiratory conditions and, consequently, will need O2. Brazil is currently facing an increase in maternal mortality from COVID-19, which may be associated with the increase in the number of cases, but also with the lack of access to the health system by pregnant and postpartum women. It is observed that of the pregnant and postpartum women who died because of COVID-19 in Brazil, one in five was not admitted to the intensive unit care and one in three did not have access to the orotracheal intubation.4 The risk factors for oxygen supplementation found in this study can be extremely important to identifying the group of pregnant and postpartum women with a higher risk of needing O2 and, consequently, a greater chance of being admitted to intensive unit care or mechanical ventilation. This can reduce maternal mortality, both in Brazil and in those who observed an increase in maternal mortality due to COVID-19.

Strengths and limitationsThe strength of this study is the access to clinical, laboratory, and history data of a relevant number of pregnant and postpartum women with COVID-19, admitted to a single hospital, followed by the same protocol, a fact not observed in other studies.9,10,15-18 As a limitation of the study, a considerable percentage of pregnant women were admitted while already receiving O2, making it impossible to obtain a predictive model of O2 requirement, though not invalidating the proposed analysis of risk factors.

Another limitation of the study was that sociodemographic characteristics such as income, education, and ethnicity, which are correlated with causes of higher risk of contamination and worse outcomes,4-6 were not collected at the time of patient inclusion.

ConclusionsIn pregnant women, a population at higher risk for developing critical forms of COVID-19, BMI ≥ 30, smoking, chronic hypertension, obstetric reasons for hospitalization, respiratory rate ≥ 24 cycles/min, O2 saturation < 95%, ground glass on CT and combination of altered laboratory parameters were identified as risk factors for oxygen need. These findings help to define the population with the greatest chance of clinical deterioration and who need access to more resources in health care systems.

Authors' contributionsConceptualization: F.S.B., M.L.B. and R.P.V.F; Data collect: F.S.B., C.F.P., U.T.G. and HC-FMUSP-Obstetric COVID-19 Study Group; Formal analysis: F.S.B., S.V.P. and R.P.V.F.; Methodology: F.S.B., M.L.B. and R.P.V.F; Supervision: R.P.V.F.; Writing ‒ original draft: F.S.B.; Writing ‒ review & editing: L.M.M., M.L.B. and R.P.V.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FundingCAPES (88881.504727/2020-01) and HCComvida (02.25). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Hospital das Clínicas (CAAE: 30270820.3.0000.0068).

Informed consentAll the patients signed informed consent.

HC-FMUSP-Obstetric COVID-19 Study Group: Aline Scalisse Bassi; Amanda Wictky Fabri; Ana Claudia Rodrigues Lopes Amaral de Souza; Ana Claudia Silva Farche; Ana Maria Kondo Igai; Ana Maria da Silva Sousa Oliveira; Adriana Lippi Waissman; Carlos Eduardo do Nascimento Martins; Danielle Rodrigues Domingues; Fernanda Cristina Ferreira Mikami; Jacqueline Kobayashi Cippiciani; Jéssica Gorrão Lopes Albertini; Joelma Queiroz de Andrade; Juliana Ikeda Niigaki; Marco Aurélio Knippel Galletta; Mariane de Fátina Y. Meda; Mariana Yumi Miyadahira, Mariana Vieira Barbosa; Monica Fairbanks de Barros; Nilton Hideto Takiuti; Sckarlet Ernandes Biancolin Garavazzo; Silvio Martinelli; Tiago Pedromonico Arrym; Veridiana Freire Franco.