Cryptococcosis is still a life-threatening mycosis that continues to be of serious concern in Latin American countries, especially among HIV+positive population. However, there is not any reliable information about the prevalence of this disease in this region.

AimsThe aim of this study is to report data of 2041 patients with cryptococcosis that were attended at the Infectious Diseases Hospital F. J. Muñiz over a 30 year-period.

MethodsInformation about demographic and clinical data, survival time and the applied treatment, was taken from the Mycology Unit database. Mycological exams from different clinical samples were performed. Cryptococcal capsular antigen in serum and cerebrospinal fluid was detected through the latex agglutination technique. Cryptococcus isolates were phenotypically identified and the genotype was determined in some of them. Susceptibility tests were carried out following M27-A3 document.

ResultsSeventy five percent of HIV+positive patients and 50% of the HIV-negative population were males. Mean ages were 34.1 in HIV+positive patients and 44.8 in the HIV-negative. Cryptococcosis was associated with AIDS in 98% of the cases. Meningeal compromise was seen in 90% of the patients. Although cerebrospinal fluid rendered more positive results, blood culture was the first diagnostic finding in some cases. Cryptococcal antigen showed positive results in 96.2% of the sera samples and in the 93.1% of the cerebrospinal fluid samples. Most of the isolates were Cryptococcus neoformans and belonged to genotype VNI. Minimal inhibitory concentration values were mostly below the epidemiological cutoff values.

ConclusionsWe observed that thanks to a high level of clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, combined therapy and intracranial pressure control by daily lumbar punctures, the global mortality rate has markedly decreased through the years in the analyzed period.

La criptococosis es una micosis grave y un motivo de preocupación en América Latina, en especial en los pacientes positivos para el VIH. Sin embargo, no existen aún datos regionales fiables acerca de la prevalencia de la enfermedad.

ObjetivosPresentar los datos de 2.041 pacientes con criptococosis atendidos en la Unidad de Micología del Hospital de Infecciosas F. J. Muñiz de Buenos Aires, recogidos en un período de 30 años.

MétodosSe presentan datos demográficos, diagnósticos, clínicos y el tiempo de supervivencia de los pacientes, obtenidos de la base de datos de la Unidad de Micología. Se realizaron exámenes micológicos de diversas muestras clínicas, además de antigenemia y antigenorraquia por aglutinación de látex para Cryptococcus en el momento del diagnóstico y durante el seguimiento. Se llevó a cabo la identificación fenotípica de los aislamientos y en numerosos casos también se efectuó la genotipificación. La determinación de los valores de concentración mínima inhibitoria frente a diversos antifúngicos se realizó según el documento M27-A3 (CLSI).

ResultadosEl 75% de los pacientes positivos para el VIH y el 50% de los no portadores eran varones; la media de edad fue 34,1 años para los positivos para el VIH y 44,8 para los no portadores. La criptococosis se asoció con el sida en el 98% de los casos y el 90% de ellos presentó compromiso meníngeo. Aunque la muestra clínica con mayor porcentaje de resultados positivos fue el LCR, en numerosas ocasiones el hemocultivo fue el primer elemento diagnóstico. La antigenemia fue positiva en el 96,2% de los casos y la antigenorraquia en el 93,1%. La mayor parte de las cepas era Cryptococcus neoformans y pertenecía al genotipo VNI, y la concentración mínima inhibitoria en las pruebas de sensibilidad a los antifúngicos de la mayoría de ellos mostró valores inferiores al punto de corte epidemiológico.

ConclusionesObservamos que un alto nivel de sospecha clínica, el diagnóstico temprano, el tratamiento combinado y el control de la presión intracraneal mediante punciones lumbares diarias han permitido disminuir la mortalidad global a lo largo de los años en el período analizado.

From the onset of the AIDS’ pandemic, cryptococcosis has been one of the opportunistic infections associated with this condition, being the third most frequent mycoses after oropharyngeal candidiasis and pulmonary pneumocystosis.54 Cryptococcosis annual incidence in industrialized countries reaches 2–3% and goes higher in developing countries such as Argentina, where it is about 8–10% in HIV-positive patients requiring hospitalization. Approximately one million new cases of cryptococcal meningitis are registered annually and 650,000 of them die as a result of this mycosis.60 Although these figures seem to have decreased slightly,63 in Latin American countries the amount of cases continues to be of serious concern. There is not available information about the global prevalence of this disease in the region, and there is only isolated data from the national surveillance in some countries like Colombia.30,31

The first case of cryptococcosis associated with AIDS at the Infectious Diseases Hospital F. J. Muñiz was diagnosed in 1983. In the nineties of the last century approximately 3 new cases per week were attended, and in the last 5 years 60 new patients on average have been diagnosed yearly in this institution. At the present time, it is still the most frequent systemic mycosis in HIV-infected patients in the former hospital followed by pneumocystosis and histoplasmosis.

As cryptococcosis notification is not mandatory in Argentina there is not available information about its incidence and prevalence. According to unpublished statistical data of Buenos Aires Mycology Net, near 50% of AIDS related cryptococcosis diagnosed and treated in Buenos Aires City belong to F. J. Muñiz Hospital. The aim of this study is to show the Mycology Unit experience in the diagnosis of cryptococcosis, and clinical features, therapeutics and progress of patients attended at the F. J. Muñiz Hospital in the last 30 years.

Materials and methodsPatientsMycology Unit database was used to obtain the information about cryptococcosis in patients diagnosed or attended at the F. J. Muñiz Hospital between January 1986 and December 2015. When available, a retrospective analysis of the demographic data, such as underlying conditions, lesion localization, clinical and images features, CD4+ counts, clinical samples used for diagnosis, cryptococcal polysaccharide capsular antigen titers (in serum and cerebrospinal fluid – CSF), molecular identification of the isolates and their antifungal susceptibility, treatment schemes and survival time, was carried out.

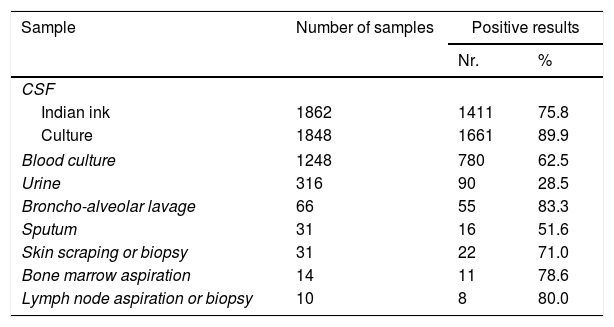

Diagnostic methodsDirect examination and cultures were made on the following clinical samples: CSF, blood, muco-cutaneous scrapings, urine, skin and other organ biopsies, lymph node and bone marrow aspirations, bronchoalveolar lavages, sputa or other bronchial secretions, peritoneal and pleural fluids, and other clinical samples (Table 3). All the samples were processed according to the standard methodology of the Mycology Unit.5,8–10,37 Alcian blue or mucicarmin stains were used in histopathological preparations.17,22

Phenotypical differentiation between Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii was carried out by seeding on glycine-canavanin-bromothimol blue agar (GCB) and glycine-cycloheximide-phenol red agar (Salkin medium).43,65 Molecular identification through PCR-RFLP of URA5 gen was carried out in some of the isolates. PCR products were subjected to a double enzymatic digestion with Sau96I and HhaI, and restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis in agarose gel and compared with the patterns obtained from the following reference strains: C. neoformans var. grubii: CBS 10085 VNI, CBS 10084 VNII; C. neoformans hybrid AD: CBS 10080 VNIII; C. neoformans var. neoformans: CBS 10079 VNIV; and C. gattii: CBS 10078 VGI, CBS 10082 VGII, CBS 10081 VGIII, and CBS 10101 VGIV.16,51,52

Presence and titer of capsular polysaccharide antigen (CrAg) in serum and CSF were determined by the latex agglutination technique (LA) (IMMY, Immunomycologics, Norman Kew Surrey, OK, USA) at diagnosis and during the follow up. Lateral flow chromatography (LFC) (IMMY, Immunomycologics) was just used in the last three years (209 samples) in patients with a clinical suspicion of the disease; whenever the test was positive, the titer was determined by LA, and CSF and other samples were taken to confirm the cryptococcosis. In order to determine the CrAg titer in HIV patients the following serum and CSF dilutions were used: 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000, 1:5000 and 1:10,000. In the case of HIV-negative patients the standard dilutions (1:2n) were tested.5

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) by means of the broth microdilution technique according to M27-A3 and M27S4 documents of the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute – USA, were assessed to study the antifungal susceptibility of Cryptococcus isolates to amphotericin B (AMB) (Sigma–Aldrich, USA), fluconazole (FCZ) and voriconazole (VCZ) (Pfizer, UK), itraconazole (ITZ) (Panalab, Argentina), posaconazole (PCZ) (Schering-Plough, USA), and albaconazole (ABZ) (Uriach, Spain).19,20 As clinical cutoff-values for Cryptococcus are not still determined, the epidemiological cutoffs (ECV) were used as reference.32

Statistical analysisData from continuous variables were expressed as average with its standard deviation or as median with its interquartile range as appropriate. MIC values were also presented as geometric means and ranges. The categorical variables were expressed as percentages. For continuous variables, analysis of variance or Student's t test were used to evaluate statistical differences; for the categorical data Z-test (for proportions) or χ2 test were employed. The difference was considered significant when the p-value was less than 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed with the Statistix® 8.0 software.

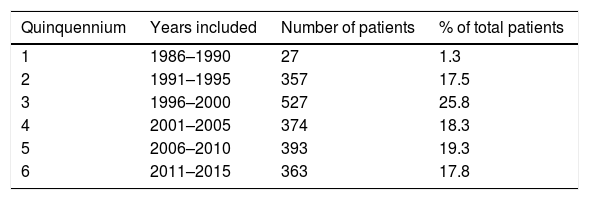

ResultsPatientsThe data of 2041 patients were included. Two thousand individuals were HIV+positive and only 41 were HIV-negative; 1923 were attended at the F. J. Muñiz Hospital from the onset of the mycosis (1800 cases) or were received at the already mentioned institution after being treated in other hospitals (123 cases). Clinical samples from the remaining 118 cases were just referred to the Mycology Unit for diagnosis, identification of the isolate, capsular antigen detection and antifungal susceptibility test determination. The number and percentage of the patients included are presented in Table 1.

- a.

Characteristics of HIV-positive patients (2000 cases)

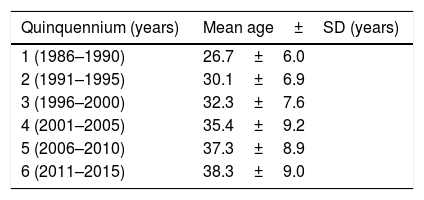

The mean age of this group of patients was 34.1±8.1 years (median age: 33; range: 12–68 years), and there was not statistical difference between both sexes (p=0.4413) with respect to the age. On the other hand a statistically significant increase in the patients’ age along the six five-year periods considered was observed (p=0.0006) (Table 2). One thousand fifty hundred and sixteen patients were males (75.8%) and 484 (24.2%) were females (rate 3:1 during the six periods). The median of the CD4+ lymphocyte subset count at diagnosis of 625 patients was 35 cells/μl and the interquartiles range 15–70 cells/μl.

Direct microscopy observation with Indian ink was performed on 1862 CSF sediments; mycological culture was performed in only 1848 CSF samples. Both tests were carried out in 1819 CSF samples with the following results: Indian ink and culture were positive in 1331 samples (73.2%), in 306 samples (16.8%) only the culture was positive, and in 47 samples (2.6%) Indian ink preparation was positive and the culture was negative; these samples were collected from patients previously treated in other institutions. In 135 (7.4%) both determinations were negative, especially in individuals without meningeal compromise. Considering the 6 quinquennia analyzed, the amount of CSF positive cultures only showed statistical differences between the second (94.3%) and the fifth period (84.9%) (p=0.0001). A total of 1248 blood cultures were processed at diagnosis, and criptococcemia was detected in 780/1248 (62.5%) cases. Variations among the 6 quinquennia ranged from 52.8% (5th period) to 66.3%, (2nd period) (p=0.015). C. neoformans was recovered from both CSF and blood cultures in 648/1166 (55.6%) cases in which the two samples were studied at diagnosis. Another 493 specimens from different lesions were also cultured. The performance in diagnosing cryptococcal infection of all the analyzed samples is shown in Table 3. C. neoformans was found in 4074/5451 (74.7%) clinical samples at the onset of the mycosis.

Clinical samples in HIV+positive patients.

| Sample | Number of samples | Positive results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nr. | % | ||

| CSF | |||

| Indian ink | 1862 | 1411 | 75.8 |

| Culture | 1848 | 1661 | 89.9 |

| Blood culture | 1248 | 780 | 62.5 |

| Urine | 316 | 90 | 28.5 |

| Broncho-alveolar lavage | 66 | 55 | 83.3 |

| Sputum | 31 | 16 | 51.6 |

| Skin scraping or biopsy | 31 | 22 | 71.0 |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 14 | 11 | 78.6 |

| Lymph node aspiration or biopsy | 10 | 8 | 80.0 |

Other positive samples: pleural effusion (7), ascitic fluid (4), panniculitis (1), palate lesion (1), knee lesion (1), and biopsies from brain (1), lung (4), and duodenum (1).

Isolates from 1916 patients were phenotypically identified, and the causal species were C. neoformans in 1914 and C. gattii in two. One hundred and thirty two C. neoformans isolates were genotyped and 121 (91.7%) belonged to VNI genotype, 4 (3%) to VNII, 5 (3.8%) to VNIII and 2 (1.5%) to VNIV. Both C. gattii isolates were identified only phenotypically.

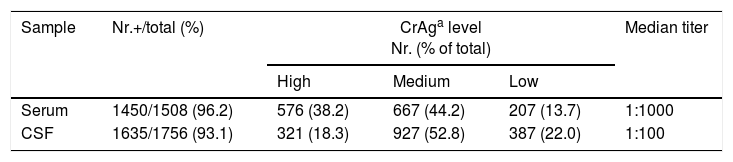

Capsular polysaccharide antigen (CrAg) detection in serum and CSF at diagnosisA total of 1508 serum samples allowed us to detect CrAg by LA in 1450 (96.2%) of the patients. CrAg screening in CSF was carried out in 1756 samples and the test was positive in 1635 (93.1%) (Table 4). LFA was performed at diagnosis in 26 sera and 14 CSF samples of patients with cryptococcosis. The results were coincident with those of LA except for one CSF sample with a positive result by LFA and a negative one by LA; in another case only LFA could be done due to the high CSF protein concentration, which hindered the performance of LA test. LFA was also carried out in 112 sera and 57 CSF samples of patients without cryptococcosis, with a negative result in all the cases.

Results of cryptococcal capsular antigen detection by latex agglutination test.

| Sample | Nr.+/total (%) | CrAga level Nr. (% of total) | Median titer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | |||

| Serum | 1450/1508 (96.2) | 576 (38.2) | 667 (44.2) | 207 (13.7) | 1:1000 |

| CSF | 1635/1756 (93.1) | 321 (18.3) | 927 (52.8) | 387 (22.0) | 1:100 |

| Relation between mycological exams from 1688 CSF samples with their CrAg level and 1043 blood cultures with the corresponding CrAg serum level at diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF | CrAg CSF level | ||||

| Culture | Indian ink | High | Medium | Low | Negative |

| Negative | Negative | 2 | 10 | 40 | 66 |

| Positive | 4 | 23 | 11 | 3 | |

| Positive | Negative | 13 | 97 | 143 | 31 |

| Positive | 296 | 775 | 169 | 5 | |

| Blood culture | CrAg serum level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 97 | 213 | 92 | 23 |

| Positive | 354 | 218 | 39 | 7 |

In order to compare the culture results and the data of CrAg titers by LA in CSF and serum, CrAg titers were divided in three categories: low (≤1:10), medium (1:100 to 1:1000) and high (≥1:5000). The relation between CrAg concentration in CSF and blood culture of 1688 CSF samples and 1043 blood samples are presented in Table 4. Samples with positive Indian ink and CSF culture assembled 94% (296/315) of high CrAg in CSF. On the other hand, 89.8% of negative CSF samples (Indian ink and culture) showed low level or negative CSF CrAg titers. Serum CrAg titers ≥1:5000 from 354/451 (78.5%) cases corresponded to patients with positive blood cultures, and 115/161 (71.4%) with low or negative CrAg serum level belonged to patients with negative blood cultures. CrAg test both in blood and CSF at diagnosis was determined in 1364 individuals. High CrAg levels were simultaneously found in serum and CSF in 166 (12.1%) patients, and 63.3% of them also had positive CSF and blood cultures (p<0.0001), 23 had negative blood culture and in 32 patients a blood culture was not performed. Medium CrAg titer in CSF and serum was found in 384 patients (28.2%), and low level or negative CrAg in both fluids in 167 patients (12.2%). CrAg high titers were found in 64.7% of the sera and 39.3% of CSF in patients who died within the first week after cryptococcosis was diagnosed. Conversely, those patients who survived showed high CrAg levels only in 31.6% of the sera and 15.6% of CSF samples (p<0.0001).

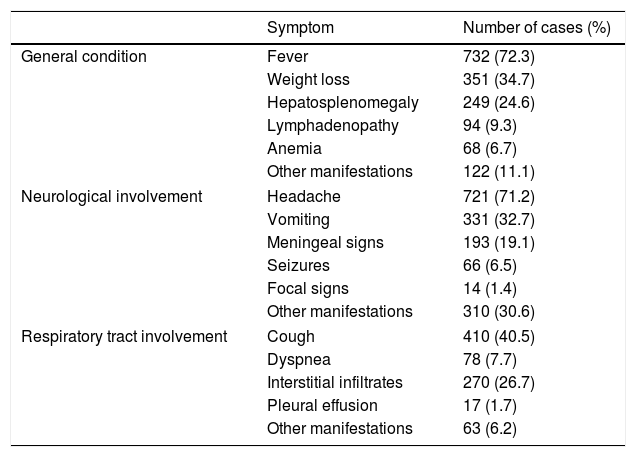

Clinical dataMeningeal cryptococcosis in AIDS patients was the most frequent clinical presentation (90%). Clinical information was recovered from the Mycology Unit clinical records in 1012 cases. Signs and symptoms of the patients are presented in Table 5. Fever (72.3%) and headaches (71.2%) were the most habitual symptoms. Patients suffering meningoencephalitis presented incomplete meningeal syndrome, vomiting, photophobia, visual alterations, blindness,25 diarrhea, anorexia and asthenia. Seizures and focal signs were much less frequent. Four hundred an ten patients (40.5%) had respiratory involvement, and hepatosplenomegaly was observed in 249 (24.6%). Hepatosplenomegaly was recognized in all these patients by ultrasonography. The etiology of this clinical finding was not established, and may be due not only to the cryptococcosis but to several other diseases that these patients suffer simultaneously, including the advanced HIV infection.

Main signs and symptoms in HIV patients.

| Symptom | Number of cases (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| General condition | Fever | 732 (72.3) |

| Weight loss | 351 (34.7) | |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 249 (24.6) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 94 (9.3) | |

| Anemia | 68 (6.7) | |

| Other manifestations | 122 (11.1) | |

| Neurological involvement | Headache | 721 (71.2) |

| Vomiting | 331 (32.7) | |

| Meningeal signs | 193 (19.1) | |

| Seizures | 66 (6.5) | |

| Focal signs | 14 (1.4) | |

| Other manifestations | 310 (30.6) | |

| Respiratory tract involvement | Cough | 410 (40.5) |

| Dyspnea | 78 (7.7) | |

| Interstitial infiltrates | 270 (26.7) | |

| Pleural effusion | 17 (1.7) | |

| Other manifestations | 63 (6.2) | |

The central nervous system images most frequently observed were cerebral atrophy, ventricular enlargement, space-occupying mass in brain, and cerebral edema. There were no evident lesions in the brain CT scan or even in magnetic resonance imaging in many cases. The opening pressure was informed in 185 cases and it was above the normal value in 78.9% of these patients.

Interstitial infiltrates were the most prevalent pulmonary images followed by micro nodular lesions and lung nodules; cavity images were rare. Associated diseases were registered in 490 cases, and several infections were concomitantly diagnosed. Among the mycoses, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia was diagnosed in 69 patients and histoplasmosis in 31. Oral and esophageal candidiasis, and even dermatophytes infections, were also recorded. The high incidence of histoplasmosis can be explained by the fact that this mycosis is endemic in Buenos Aires city and its disseminated form is often observed in patients with advanced HIV infection.23,56,60 Prior to or concurrently with cryptococcosis, tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections were diagnosed in 51.7% (193/373). Mycobacterial infections are often detected in HIV-infected patients with low CD4+ cell counts, especially tuberculosis which presents a high prevalence in Argentina. Other bacterial pathologies were observed in 95 cases. The most frequent viral infection was hepatitis (B and C in 116 cases). Cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, Molluscum contagiosum virus and JC virus infections were also diagnosed in 99 patients. Chagas disease and toxoplasmosis (47 cases) were diagnosed among other parasitic infections. Diabetes was registered in 26 cases and other non-infectious diseases in 41.

TreatmentAt the beginning of AIDS pandemic, 5-fluorocytosine (FC) was available in Argentina, and the standard treatment scheme during the first 2 quinquennia was the association of amphotericin B (AMB) with FC. As a result of FC discontinuity, treatment consisted of AMB alone for 2–3 weeks, followed by fluconazole (FCZ) by oral route. At the F. J. Muñiz Hospital, the combination of intravenous AMB (0.7mg/kg daily) and FCZ (800mg/day orally) at the beginning of the treatment, followed by FCZ alone for maintenance, has been the therapeutic scheme since 2010.49

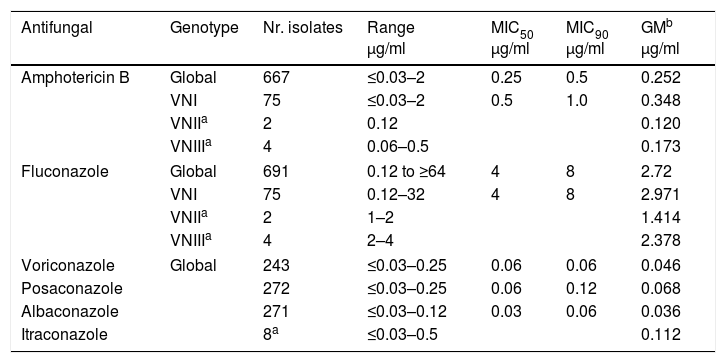

Antifungal susceptibility of the isolatesMICs to the following antifungal drugs were determined: FCZ, AMB, ITZ, PCZ, ABZ and VCZ. The number of C. neoformans isolates studied for each drug along with MICs values are presented in Table 6. AMB was tested on 667 C. neoformans, and nearly all showed a MIC value ≤1μg/ml, except for 4 isolates which had a value of 2μg/ml. Susceptibility to FCZ was determined in 691 isolates. Only in 22 MIC was 16μg/ml, in 5 cases the MIC value was 32μg/ml and in another 6 isolates it was ≥64μg/ml. Therefore only 1.6% of the isolates presented MICs above the ECV (95% ECV 16μg/ml; 99% ECV 32μg/ml).32

Susceptibility test results of C. neoformans isolates to different antifungal drugs.

| Antifungal | Genotype | Nr. isolates | Range μg/ml | MIC50 μg/ml | MIC90 μg/ml | GMb μg/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | Global | 667 | ≤0.03–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.252 |

| VNI | 75 | ≤0.03–2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.348 | |

| VNIIa | 2 | 0.12 | 0.120 | |||

| VNIIIa | 4 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.173 | |||

| Fluconazole | Global | 691 | 0.12 to ≥64 | 4 | 8 | 2.72 |

| VNI | 75 | 0.12–32 | 4 | 8 | 2.971 | |

| VNIIa | 2 | 1–2 | 1.414 | |||

| VNIIIa | 4 | 2–4 | 2.378 | |||

| Voriconazole | Global | 243 | ≤0.03–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.046 |

| Posaconazole | 272 | ≤0.03–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.068 | |

| Albaconazole | 271 | ≤0.03–0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.036 | |

| Itraconazole | 8a | ≤0.03–0.5 | 0.112 | |||

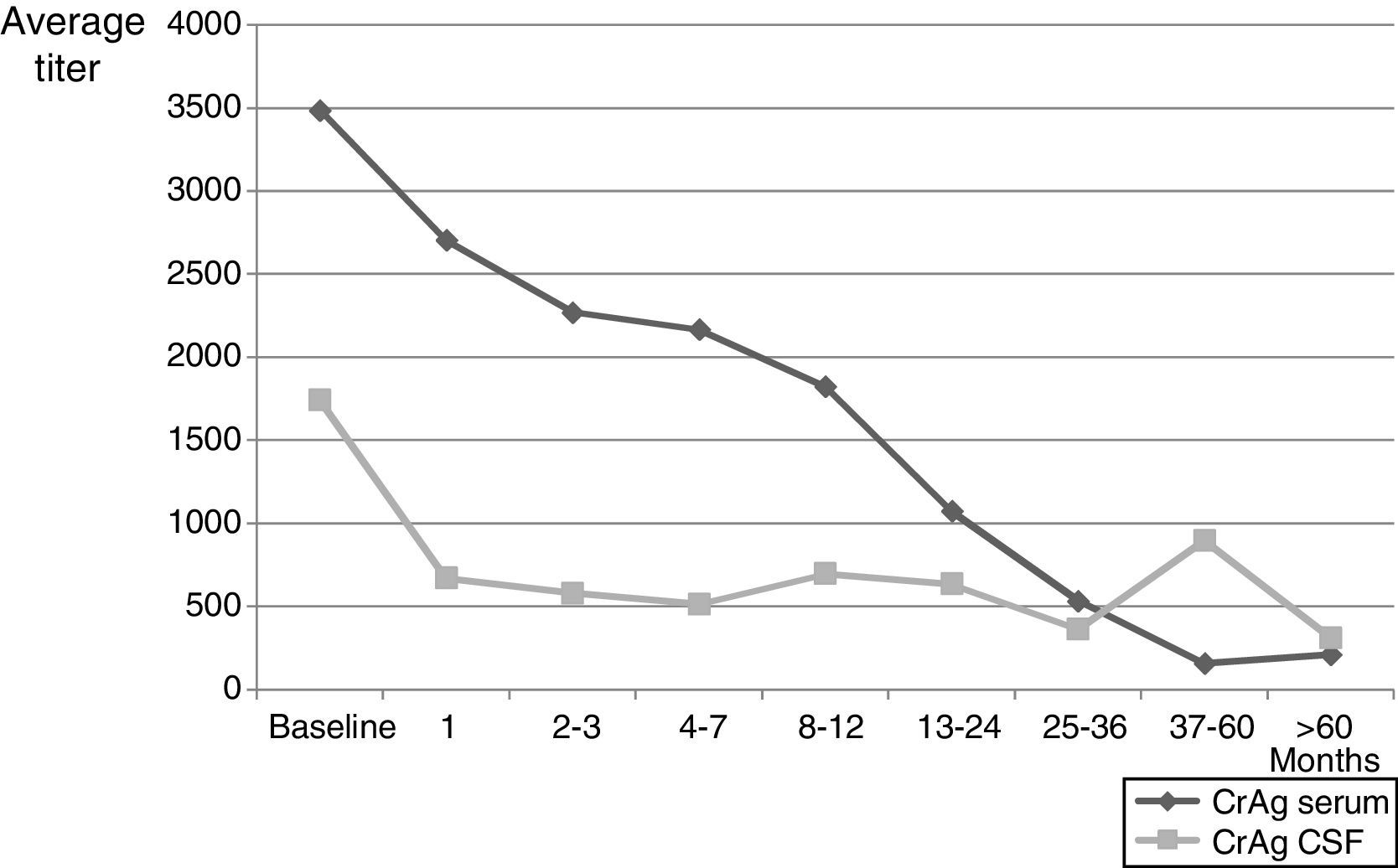

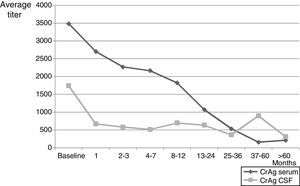

A total of 1798 patients were followed at the Mycology Unit for pretty variable periods that varied between a week and more than 17 years. One hundred and four individuals passed away in less than one week after the diagnosis and some of them the same day they were hospitalized; in another 202 cases no control was done after the diagnosis. The maximum survival time of those patients who died (792 cases) was 3410 days (more than 9 years) and for those who did not die during the control period (1006 cases) was about 17.2 years. During the follow up, between 1 and 20 mycological exams per patient were carried out on different samples, and C. neoformans grew in 292 blood cultures (from 240 patients), 1301 CSF (669 patients), 23/31 urine specimens, 6 sputa, 15 bronchoalveolar lavages, 3 lymph node punctures, 2 skin lesions, 2 hepatic biopsies, 2 pleural fluids and 4 bone marrow aspirations. Negative CSF cultures were obtained between the first and second month of treatment in many cases, even though few patients needed 4–5 months for their CSF cultures to turn negative. One of the parameters used in the follow up period was CrAg, both in serum and in CSF (when lumbar puncture was done). Mean data of CrAg through control period are shown in Fig. 1. The first antigen determination was carried out 3–4 weeks after the diagnosis and then it was repeated monthly or bimonthly during the first year and, after that, either every 3–4 months or when the patient was attended at the Mycology Unit for a clinical control. A total of 2464 serum samples and 2047 CSF samples were evaluated. CrAg serum titers were habitually equal or higher to the ones obtained in CSF. The values obtained with this last test decrease after 2–3 months, when most CSF cultures became negative (even when encapsulated yeasts were seen in Indian ink preparations).

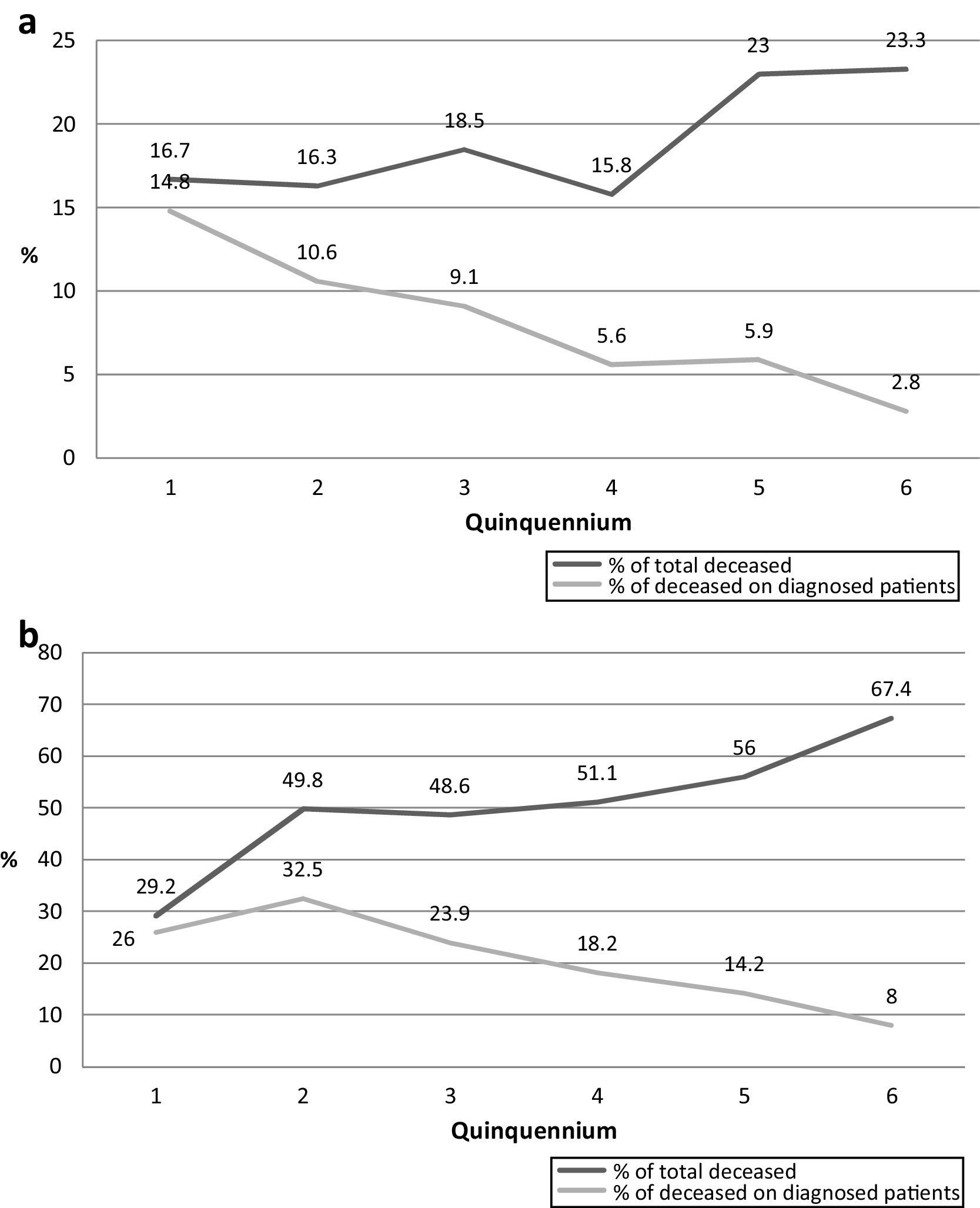

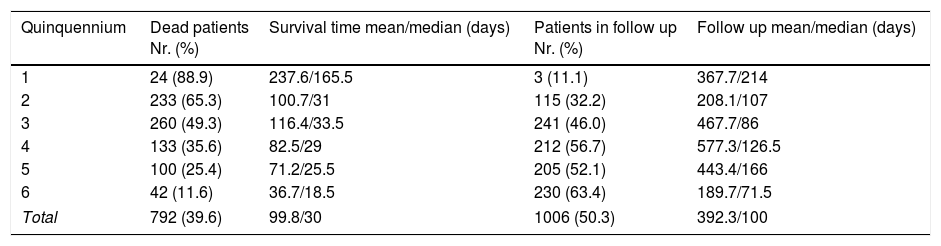

Survival time through the six analyzed quinquenniaThe mean survival time since the diagnosis of cryptococcosis in all the studied patients is presented in Table 7. The number of deceased patients in each quinquennium decreased from 88.9% in the first period to 11.6% in the last one. The survival time of those patients became shorter through the 6 periods as many deaths took place in the first weeks of the last quinquennia as shown in Fig. 2. All through the years the percentage of deaths during the first week diminished from 13.2% (2nd period) to 3.8% (6th period) (p=0.0001). However, this was not observed in the first quinquennium. This decrease was similar in the deaths of the first month (35% to 10.4%; p<0.0001). Nevertheless, when the number of deaths during the first week or month was compared with the total number of dead patients of each quinquennium, an increasing proportion was observed in the first weeks (from 12.5 to 24.4%; p=0.3417 in the first week and from 33.3 to 65.9% during first month; p=0.0195).

- b.

Characteristics of HIV-negative patients

Survival time, and number of deceased and alive patients until the last clinical control of 2000 HIV-positive individuals diagnosed along the 6 quinquennia (n=1798 patients).

| Quinquennium | Dead patients Nr. (%) | Survival time mean/median (days) | Patients in follow up Nr. (%) | Follow up mean/median (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 (88.9) | 237.6/165.5 | 3 (11.1) | 367.7/214 |

| 2 | 233 (65.3) | 100.7/31 | 115 (32.2) | 208.1/107 |

| 3 | 260 (49.3) | 116.4/33.5 | 241 (46.0) | 467.7/86 |

| 4 | 133 (35.6) | 82.5/29 | 212 (56.7) | 577.3/126.5 |

| 5 | 100 (25.4) | 71.2/25.5 | 205 (52.1) | 443.4/166 |

| 6 | 42 (11.6) | 36.7/18.5 | 230 (63.4) | 189.7/71.5 |

| Total | 792 (39.6) | 99.8/30 | 1006 (50.3) | 392.3/100 |

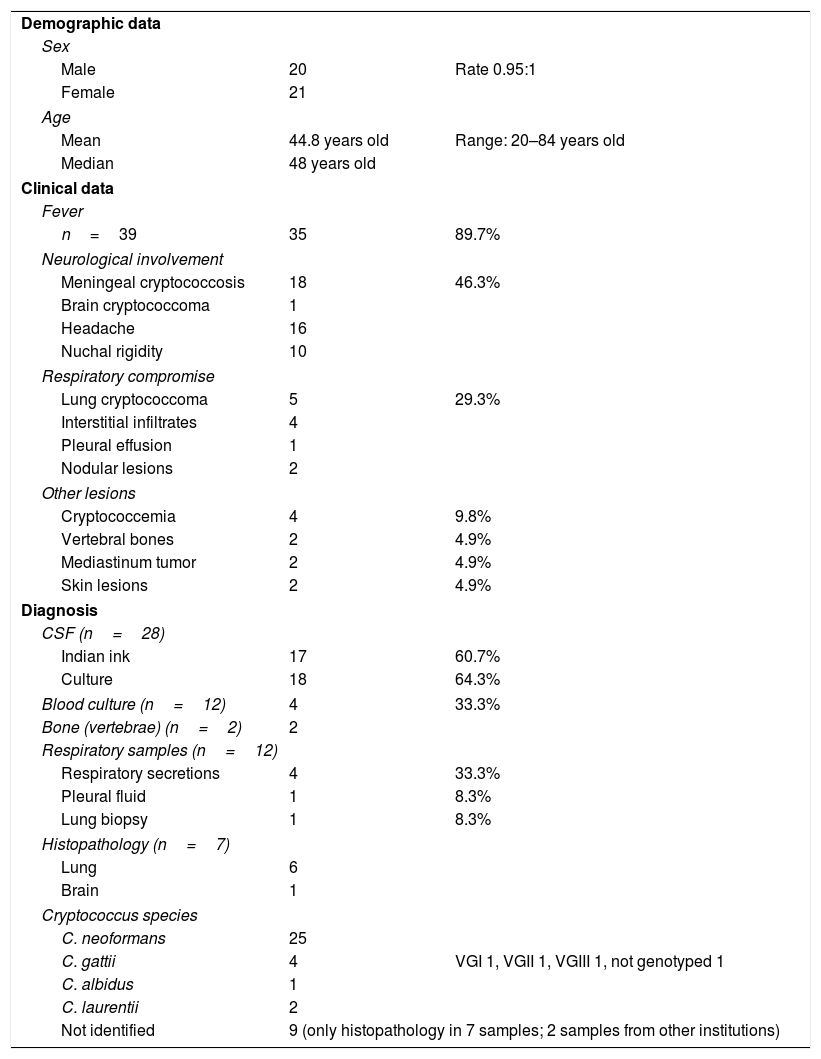

The principal characteristics of the 41 HIV-negative cases of cryptococcosis are presented in Table 8.

Characteristics of the 41 HIV-negative patients with cryptococcosis.

| Demographic data | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 20 | Rate 0.95:1 |

| Female | 21 | |

| Age | ||

| Mean | 44.8 years old | Range: 20–84 years old |

| Median | 48 years old | |

| Clinical data | ||

| Fever | ||

| n=39 | 35 | 89.7% |

| Neurological involvement | ||

| Meningeal cryptococcosis | 18 | 46.3% |

| Brain cryptococcoma | 1 | |

| Headache | 16 | |

| Nuchal rigidity | 10 | |

| Respiratory compromise | ||

| Lung cryptococcoma | 5 | 29.3% |

| Interstitial infiltrates | 4 | |

| Pleural effusion | 1 | |

| Nodular lesions | 2 | |

| Other lesions | ||

| Cryptococcemia | 4 | 9.8% |

| Vertebral bones | 2 | 4.9% |

| Mediastinum tumor | 2 | 4.9% |

| Skin lesions | 2 | 4.9% |

| Diagnosis | ||

| CSF (n=28) | ||

| Indian ink | 17 | 60.7% |

| Culture | 18 | 64.3% |

| Blood culture (n=12) | 4 | 33.3% |

| Bone (vertebrae) (n=2) | 2 | |

| Respiratory samples (n=12) | ||

| Respiratory secretions | 4 | 33.3% |

| Pleural fluid | 1 | 8.3% |

| Lung biopsy | 1 | 8.3% |

| Histopathology (n=7) | ||

| Lung | 6 | |

| Brain | 1 | |

| Cryptococcus species | ||

| C. neoformans | 25 | |

| C. gattii | 4 | VGI 1, VGII 1, VGIII 1, not genotyped 1 |

| C. albidus | 1 | |

| C. laurentii | 2 | |

| Not identified | 9 (only histopathology in 7 samples; 2 samples from other institutions) | |

| Sample | Nr.+/total | CrAg LAa titers at diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | 35/39 | ≤1:32=11 | 1:128 to 1:1024=14 | ≥1:4096=10 |

| CSF | 25/29 | ≤1:64=11 | 1:128 to 1:1024=12 | ≥1:4096=2 |

Among the risk factors the most frequent was the renal transplant (9 cases); two patients were under corticosteroids treatment, and there was one patient with each of the following conditions: a solitary kidney, idiopathic CD4+ lymphopenia with a previous disseminated histoplasmosis, a chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, diabetes, a lupus nephritis, concomitant paracoccidioidomycosis and strongyloidiasis (a badly nourished-patient infected with C. gattii), bullous pemphigoid, Herpes Virus infection, arterial hypertension, and contact with wood dust.

DiscussionCryptococcosis is a systemic mycosis that continues causing a high number of infections in AIDS patients, mainly in not industrialized countries. The disease produces a great concern not only because of the clinical manifestations but also because of the high mortality associated with it. In 2009, Park estimated a million new cases yearly, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa (more than 700,000) with a mortality of about 600,000.62,71 Cryptococcosis in Latin-American countries account for a great number of cases, but there are only estimations of the prevalence of this mycosis based on information from research groups and not from national statistical data. In a recent epidemiological surveillance in Colombia, which covered the 1997–2014 period, a total of 1837 cases from different regions were reported, 76.9% (1413) in HIV-positive-individuals.30 Cryptococcosis is not a notifiable disease in our country and no reliable data about the real incidence of this pathology in Argentina is available. An Argentine publication accounted for a total of 105 cases widespread in the country in 1981–1990.6 A recent research done by the “Laboratorio Central de Redes y Programas” of Corrientes province informed about 26 detected cases between 2008 and 2013 in four general hospitals and one pediatric hospital. On the outskirts of Buenos Aires, 106 HIV-positive-patients (128 episodes) were attended between 1996 and 2007 at the Paroissien Hospital.53

Cryptococcosis is the most prevalent systemic mycosis in HIV+positive patients in the F.J. Muñiz Hospital. In the last years an average of 60 new cases have been diagnosed yearly, similar to those corresponding to P. jirovecii pneumonia and almost two fold the disseminated histoplasmosis. Almost half of the cryptococcosis diagnosis in Buenos Aires city and 15% of those cases from the whole country are made in this Infectious Diseases Hospital. These data show that this casuistic is very high compared to those of other institutions in Argentina and Colombia. The main risk factor in this cohort was the HIV infection (98%); this percentage was lower (76.9%) among the patients of a Colombian study in an 18 year-period.30 The high percentage of HIV-positive-patients could be explained by the fact that the F.J. Muñiz Hospital is an institution devoted to infectious diseases that assists most of the aids individuals requiring hospitalization in Buenos Aires city; on the contrary, patients with other type of immunodeficiency are habitually attended in other institutions.

Male/female rate of the presented cases was 3:1, quite similar to the findings in Paroissien Hospital (70.1% men), lower than the rate obtained in Colombia on 526 cases (83.5% males), lower than in the surveillance carried out in 1997–2014 (where rates varied from 4.7:1 to 3.1:1), and higher than the cases diagnosed in Corrientes province (2.6:1) among HIV+positive patients.15,53 The average age of the cohort studied increased through the 6 analyzed quinquennia as it happened with the HIV+positive population attending the Hospital. The mean age in the whole period was 34.1 years, with 26.7 years in the first quinquennium and reaching 38.5 years of age in the last one. In the Colombian population, 74.9% of the cases were between 21 and 50 years, and in Corrientes the median age was 38.5, the same as ours in the last quinquennium. In the cohort of Paroissien Hospital the median age was 34 years old.15,30,31,53 No statistical difference in age was found between both sexes (p=0.45). Most of the patients were in the late stages of HIV infection with a CD4+ lymphocyte median count of 35 cells/μl (interquartile range 15–70 cells/μl), being a population at high risk of suffering cryptococcosis. As it was expected, CSF was the sample rendering positive results in first place, followed by blood cultures, in consistence with previous findings in other investigations.6,46,53 The increase in the proportion of positive blood cultures and decrease in CSF positive cultures seen during the 6th quinquenium is probably due to an earlier diagnosis. Direct culture of all the samples (except blood and bone marrow aspiration) onto sunflower agar favored and accelerated the identification of this microorganism (presence of melanin pigment) and allowed the differentiation from other yeasts unable to produce melanin in materials like respiratory secretions, urine, biopsies, etc. Moreover, the quick urease detection method on filter paper brought about fast information and contributed to the early diagnosis of this mycosis.8,48

The Mycology Unit does not have proteomic equipment (MALDI-TOF) for species identification, thus yeasts belonging to the species C. neoformans and C. gattii were phenotypically differentiated by conventional methods using GCB and Salkin medium.43,64 All the isolates from HIV+positive patients were C. neoformans except for two C. gattii (0.1%). The last species was the causing agent in four HIV-negative patients (9.7%). Recently, the molecular identification by PCR-RFLP of URA5 gene in isolates from several periods included in this study was carried out. In this cohort 91.7% of C. neoformans isolates belonged to VNI genotype as it was found in other investigations. In 2003, the research performed with Spanish and Latin American environmental and clinical isolates, showed that 29/33 (87.9%) samples from HIV-positive patients from the F.J. Muñiz Hospital were VNI, 2 VNII and the remaining 2 VNIII, Considering all the Argentinean isolates, 57 (82.5%) were VNI, 8.9% VNII, and 3.6% VNIII.51 Another investigation on C. neoformans isolates in Corrientes province found that 15/18 cases belonged to VNI genotype, 1 to VNII, and 2 to VNII-VNIV hybrid.15 In the Perrando Hospital (Chaco province) 15/16 isolates from HIV-positive patients were VNI and 1 C. gattii VGI.16 A global research carried out with clinical and environmental isolates in different world regions showed similar results: VNI genotype was the most prevalent all over the world and 60/87 isolates from Argentina were VNI, as 71% of Latin-American isolates.21,33. On the other hand, a recent publication from Seville, Spain, showed that 64% of 28 isolates from 12 HIV-positive patients were C. deneoformans or C. deneoformans × C. neoformans hybrids.35

Another useful tool in the diagnose of the disease and the progress of the patients was the detection of CrAg in serum and CSF. In this study LA method was always used with the same kit (IMMY), with diagnostic and evolution control purposes. In order to compare the results it is very important using the same equipment since it has been shown that there is a marked difference in sensitivity among different commercial kits, which makes the comparison of data impossible.29,39,67 Lateral flow chromatography (LFA) kit (IMMY) began to be commercialized in Argentina three to four years ago. There are many publications that demonstrate its great sensitivity (superior to LA) and specificity.4,41,42,45,66,73 Currently, LFA is used in the Mycology Unit as a diagnostic tool in HIV-positive patients at risk of suffering cryptococcosis. If this test brings a positive result, the titer is determined by LA and different samples (especially CSF and blood) are further studied to microbiologically confirm the mycosis. Twenty years ago a research was carried out in order to make an early diagnosis of cryptococcosis in patients at risk (CD4+ counts <300 cells/μl, fever, without meningeal symptoms). It was done using LA and EIA tests on 193 patients. Seroprevalence of CrAg was 6.7% (13/193 patients) and only in three of them the cryptococcosis was microbiologically confirmed.58 CrAg titer in serum and CSF is useful as an indirect measure of fungal load; during the follow up period the titer decrease is consistent with the patient improvement. In our study, this fact was more evident with CSF samples because low titers corresponded to negative cultures (67.4% of negative CSF showed titers ≤1:10 in the second month after diagnosis) even when Indian ink still showed encapsulated yeasts. Serum titers diminished more slowly and more time was required to obtain negative results.3,13,29,36 This long follow up of CrAg titer in serum and CSF allowed us to observe negative results of these tests in patients after 18 or more months of secondary prophylaxis and HAART.59

The clinical symptoms and the location of the lesions were similar to the data presented in other publications.34,47,54,55,64 Meningoencephalitis was the most frequent clinical form (90% of patients), and measuring opening pressure at diagnosis is a key parameter to assess the progress. Among the patients in whom this information was available, 78.9% had a high intracranial pressure, which is a sign of poor prognosis if not controlled adequately in the first days of hospitalization, as demonstrated in previous research.11,24,27 Cerebral CT scan without contrast rarely shows pathologic findings; nevertheless brain magnetic resonance without gadolinium seems to be more sensitive and will show CNS images compatible with meningeal cryptococcosis. In a reduce number of cases they are observed as images with high signal intensities (at T2 and FLAIR), and usually correspond to enlargement of Virchow-Robin spaces, which are occupied by mucoid-protein material, affecting basal ganglia, perivascular parenchyma and, occasionally, the protuberance. Just exceptionally solid occupying lesions can be observed.26

Lung lesions appeared in 40% of the patients, but a great number of them also suffered other respiratory diseases (tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, P. jirovecii pneumonia, bacterial pneumonitis). The high frequency of respiratory involvement is due to the severe immunological compromise of this group of patients (the majority of them presented CD4+ cell counts ≤50/μl).40Cryptococcus was isolated from 82/108 respiratory samples as not always those samples were referred to a mycological study. The sunflower medium for the primary isolation of Cryptococcus in this kind of samples is notably useful since it allows brown colonies to be seen even when other yeasts are present in the same sample.48,61

Like in most Latin-American countries, 5FC has not been available for more than 2 decades in Argentina so induction therapy consisted of AMB alone. From 2010 onwards, induction treatment has been the association of AMB (0.7mg/kg daily, I.V.) with oral FCZ (800mg/day), as recommended by IDSA guides. This antifungal combination was more effective than the use of AMB alone, and cultures became negative in 3–4 weeks, as it was found in a previous research. Consolidation therapy continued with FCZ (800mg/day) and the results were very promising.49 Another investigation associated AMB with a lower dose of FCZ (400mg) during 2 weeks; the patients were followed up for only two months, and the results were not successful enough.12,69 In a meta-analysis performed by Campbell et al. the authors pointed out that in 35 investigations no evidence of a decrease in the mortality rate was observed when AMB was administered together with 5FC; moreover, they did not find any additional benefit in the AMB+FCZ combination.14 On the other hand, studies considering time and culture negativization rate found that AMB+5FC is a more effective treatment.63 In an attempt to elucidate if glucocorticosteroids could reduce mortality as in other types of meningitis, dexamethasone was combined with AMB+FCZ. The results were discouraging as there were more side effects, higher mortality rates and slower CSF clearance when compared with the control group.7 The change from induction therapy to consolidation therapy was based on CSF culture results (conversion from positive to negative). Interestingly, the cryptococcal antigen concentration in CSF was coherent with the result in the CSF culture, and in many occasions Indian ink showed encapsulated yeasts despite the low titer CrAg in CSF, thus cultures resulted negative. In this study the count of colony forming units (CFU) of CSF cultures were not carried out as a parameter to monitor fungal load and early fungicidal activity like in other investigations.63

High intracranial pressure should be controlled, especially within the 5 first days. This parameter has been taken into account considering it was previously demonstrated that when pressure continues above normal values during the mentioned period, mortality risk increases (OR 7.23, 95% CI 2.53–20.14).26 Serial lumbar punctures, even more than one a day, were useful to normalize the opening pressure in many patients.28 In those cases in which this method was unable to control the opening pressure, a ventricle-peritoneal shunt was performed with good clinical results.24

In this study, the decrease in the mortality rate (especially evident in the last quinquennium) was probably due to the control over the intracranial pressure, the combined therapy and the early diagnosis. On the other hand, the number of resistant isolates (MIC above ECV) was scarce and the MIC values obtained were similar to those found in VNI strains from Brazil.68 Therapeutic response and outcome were independent from MIC values, as it was seen in Colombian patients1 but different from findings that showed a correlation between the treatment failure and MICs≥16μg/ml in Spain.2 Nevertheless, heteroresistance should be considered in those patients with delayed negative CSF cultures.18

In this cohort the frequency of cryptococcosis in HIV-negative patients was very low (2%). In countries at other latitudes, like China or Iran, this condition is more frequent in HIV-negative individuals, probably due to genetic factors related to immunity (Han population in China). C. neoformans VNI and C. gattii VGI genotypes are prevalent there, in the manner of Australian isolates.33 Most cases corresponded to renal transplanted patients, and according to some publications it is important to consider the possibility of cryptococcosis in of organ donor transmission. Transplant candidates with cirrhosis should also be considered at risk. Early diagnosis with LFC in this group is highly recommended.38 Another risk factor associated with female cryptococcosis is systemic lupus erythematous or other autoimmune diseases, as it was seen in 2 of our patients.75 Other risk factors to be considered are diabetes and corticosteroids, as it was observed in this group and also in 5/6 cases in an intensive care unit in Arkansas.44,70 This seems to be also a predisposing factor in HIV-positive individuals according to a previous study.50

Based on the data obtained through 30 years, it can be concluded that meningoencephalitis has been the predominant clinical form, frequently with few symptoms (headache and fever as the most important ones) in cryptococcosis. C. neoformans (genotype VNI) has been isolated in most of the cases. On numerous occasions the blood culture, as well as skin or respiratory cultures, made the diagnosis possible.10,46,57,58 The use of sunflower agar in primary cultures has been of great help in these cases. Those HIV-positive individuals with CD4+ counts <100 cells/μl are at risk for this mycosis, and CrAg detection using the FLC technique in serum can be of great help for an early diagnosis.72 In Argentina, as in many countries, 5FC is not available and in the Muñiz Hospital the initial treatment with the AMB+FCZ combination has proved to be efficient. Along with a correct management of high intracranial pressure, especially in the first days, mortality rate diminished and results are encouraging. The failure in the treatment is probably due to a combination of causes more than an increased resistance to the antifungal drugs.1,74

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.