Candida auris is an emerging multidrug-resistant yeast that can cause invasive infections and is associated with high mortality. It is typically resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole and, some cases, also to echinocandins and amphotericin B. This species, phylogenetically related to Candida haemulonii, is frequently misidentified by commercial identification techniques in clinical laboratories; therefore, the real prevalence of C. auris infections may be underestimated.

AimsTo describe the clinical and microbiological features of the first four cases of C. auris fungemia episodes observed in the European continent.

MethodsThe four patients were hospitalized in the adult surgical intensive care unit. A total of 8 isolates (two per patient) from blood and catheter tip were analyzed.

ResultsAll isolates were misidentified as Saccharomyces cerevisiae by AuxaColor 2, and as Candida sake by API ID20C. VITEK MS technology misidentified one isolate as Candida lusitaniae, another as C. haemulonii and could not identify the other six. C. auris identification was confirmed by ITS rDNA sequencing. All isolates were fluconazole (MIC >256mg/l) and voriconazole (MIC 2mg/l) resistant and susceptible to posaconazole, itraconazole, echinocandins and amphotericin B.

ConclusionsC. auris should be regarded as an emerging pathogen, which requires molecular methods for definitive identification. Our isolates were highly resistant to fluconazole and resistant to voriconazole, but susceptible to the other antifungals tested, which emphasizes the importance of accurately identifying this species to avoid therapeutic failures.

Candida auris es una levadura multirresistente de reciente aparición que puede causar infecciones invasivas asociadas con una elevada mortalidad. Habitualmente, C. auris es resistente al fluconazol y el voriconazol, y en algunos casos, también a las equinocandinas y la anfotericina B. Esta especie, relacionada filogenéticamente con Candida haemulonii, no se identifica por las técnicas comerciales habitualmente disponibles en los laboratorios clínicos, por lo que la prevalencia real de las infecciones causadas por C. auris puede estar subestimada.

ObjetivosDescribir las características clínicas y microbiológicas de los cuatro primeros casos de fungemia por C. auris observados en el continente europeo.

MétodosLos cuatro pacientes eran adultos y estaban en la unidad de cuidados intensivos quirúrgicos. Se analizaron un total de 8 aislamientos (dos por paciente), obtenidos a partir de un hemocultivo y de punta de catéter.

ResultadosTodos los aislamientos se identificaron erróneamente como Saccharomyces cerevisiae por AuxaColor 2 y como Candida sake por API ID20C. El sistema VITEK MS identificó erróneamente un aislamiento como Candida lusitaniae, otro como C. haemulonii y no pudo identificar los seis aislamientos restantes. La identificación de C. auris se confirmó mediante secuenciación de la región ITS del ADNr. Todos los aislamientos fueron resistentes al fluconazol (CMI>256mg/l) y el voriconazol (CMI 2mg/l) y sensibles al posaconazol, el itraconazol, las equinocandinas y la anfotericina B.

ConclusionesC. auris es un agente patógeno de reciente aparición que actualmente solo puede ser identificado mediante secuenciación molecular. Nuestros aislamientos fueron muy resistentes al fluconazol y resistentes al voriconazol, pero sensibles a los otros antifúngicos ensayados, lo cual destaca la importancia de identificar correctamente esta especie en la práctica asistencial para evitar fracasos terapéuticos.

Candida auris is an emerging multidrug-resistant yeast that can cause invasive infections and is associated with high mortality. Since the first description by Satoh in 2009 from the ear discharge in a Japanese patient,18 several cases of nosocomial fungemia have been reported in critically ill patients from India, South Korea, South Africa, Kuwait, Venezuela and United Kingdom.3,7,8,10,11,16,17 However, the real burden of C. auris infections could be underestimated due to the fact that this species is still frequently misidentified as Candida famata, Candida haemulonii, Candida sake, Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Rhodotorula glutinis by commercial identification techniques in clinical laboratories (Vitek 2, API, AuxaColor, and MALDI-TOF).9 Additionally, C. auris is typically resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole and, in some cases, also to echinocandins and amphotericin B,5 which could explain the therapeutic failures observed in deep-seated infections caused by this species.14,16

We report four cases of C. auris fungemia identified at Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe in Valencia (Spain), all of them diagnosed in the adult surgical intensive care unit (SICU) between April and June 2016. To the best of our knowledge, we describe here the clinical and microbiological features of the first C. auris bloodstream episodes observed in continental Europe.

Case reportsCase 1A 66-year-old man who underwent liver resection due to hepatocellular carcinoma was admitted to the SICU after surgery. He developed surgical wound complications, including surgical site infection, liver abscess and evisceration. Abdominal wires were put, a negative-pressure wound therapy system was applied and antibiotics were given. Despite the treatment, the patient's condition continued worsening with fever and pleural effusion. On day 32nd of SICU stay, empirical antifungal therapy with fluconazole (400mg/day) was started. However, on day 42, C. auris was isolated from blood culture. Antifungal therapy was immediately switched to anidulafungin (200mg on day 1 followed by 100mg/day) and after 48h liposomal amphotericin B (3mg/kg/day) was added. The central venous catheter (CVC) was removed on day 43 and C. auris was recovered from the catheter tip. C. auris was also isolated from peritoneal fluid culture and from pharyngeal, rectal, and urine surveillance cultures during the first week after fungemia. Blood cultures became negative on day 57; liposomal amphotericin B was stopped on day 64 and anidulafungin 1 week after. The patient recovered completely and was discharged on day 84.

Case 2A 39-year-old woman, with severe ventricular dysfunction after prosthetic mitral valve replacement, was admitted to SICU for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. During SICU stay, she developed cardiac tamponade and a multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. The patient was treated with antibiotics, mechanical ventilation, cardiotomy and fluconazole (400mg/day) as empirical therapy. On day 59 in the SICU C. auris was isolated from blood culture and antifungal therapy was switched to micafungin (100mg/day). The CVC was removed on day 62 and C. auris was recovered from the catheter tip. C. auris was also isolated from pharyngeal, rectal, and urine surveillance cultures during the SICU stay but no abnormalities were found in the fundoscopic exam. Blood cultures became negative on day 75; however, the patient died on day 91due to multiple-organ failure caused by ventricular dysfunction.

Case 3A 48-year-old man with polytrauma after a road traffic accident was admitted to SICU due to cerebral injuries and severe thoracic trauma. Cerebral damage required emergent decompressive craniectomy and the patient was intubated, sedated, and mechanically ventilated. On day 16, he recovered and was transferred to the trauma surgery ward to continue the treatment and start rehabilitation therapy. On day 18th after hospital admission C. auris was isolated from the blood cultures, and antifungal therapy with micafungin (100mg/day) was immediately started. The CVC was removed on day 21 and C. auris was recovered from the catheter tip. C. auris was also isolated from pharyngeal, rectal, and urine surveillance cultures during the first week after fungemia. Blood cultures became negative on day 24 and micafungin treatment was maintained two weeks more. The patient responded satisfactorily to therapy and was discharged on day 44.

Case 4A 26-year-old man with polytrauma and severe cranial injury resulting from a road traffic accident was admitted to the SICU after decompressive craniectomy and maxillo-facial emergency surgery due to extensive intraparenchymal hemorrhage and cerebral edema. On day 35 of SICU stay, C. auris was isolated from blood cultures and antifungal therapy with anidulafungin (200mg on day 1 followed by 100mg/day) was started. The CVC was removed on day 40, and C. auris was recovered from the catheter tip. C. auris was also isolated from pharyngeal, rectal, and urine surveillance cultures during the post-fungemia SICU stay. Despite treatment, the patient's condition continued worsening with renal and liver failure, which required renal replacement therapies. On day 56 the patient died due to septic shock, multiple-organ failure and neurological dysfunction.

Materials and methodsPatients’ medical records were reviewed, and demographic, epidemiological, and clinical data were collected including age, gender, underlying conditions, previous exposition to antimicrobial drugs, invasive medical procedures, presence of CVC, dates of CVC removal and culturing, dates and dosages of antifungals administered, and outcome of fungemia. Mycological surveillance cultures from pharyngeal and rectal swabs, and urine were also performed weekly in all patients. Microbiological samples were processed according to the good clinical laboratory practice, including Maki and sonication techniques for catheter tip culture.

Blood cultures were collected under aseptic conditions and processed by conventional automated system (BacT/ALERT® VIRTUO™, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). All Candida isolates from blood cultures and catheter tips were identified by phenotypic and biochemical characteristics, proteomic profile and DNA sequencing technology. Phenotypic colony features were evaluated after 48h of incubation in Sabouraud dextrose agar (Becton Dickinson, Baltimore, USA), CHROMagar Candida® (Difco™, Becton Dickinson) and BBL Mycosel agar (Becton Dickinson). Biochemical characteristics were analyzed using commercial tests including API ID20C (bioMérieux) and AuxaColor™ 2 (BioRad-Laboratories, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Proteomic profiles were obtained and evaluated by VITEK MS (bioMérieux) according to manufacturer's instructions. Definitive identification was performed by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) using the primers ITS3-ITS4 and ITS2-ITS5 previously described1; sequencing reaction was performed using GenomeLab™ GeXP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) equipment and the sequences obtained were compared with those in Microbial Genomes BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/guide/sequence-analysis/). A similarity of ≥97% was used as the criterion for species identification. ITS sequences (GenBank accession no. KJ126759, KC692045) of our isolates shared a 95–99% similarity with the ITS sequences of several C. auris strains. The similarity with the isolate from Japan (Satoh, K. 2009 GenBank accession no. AB375772)18 was 94–96%.

In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing against amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, flucytosine, caspofungin, anidulafungin, and micafungin was performed by the colorimetric microdilution panel Sensititre Yeast One®Y010 (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

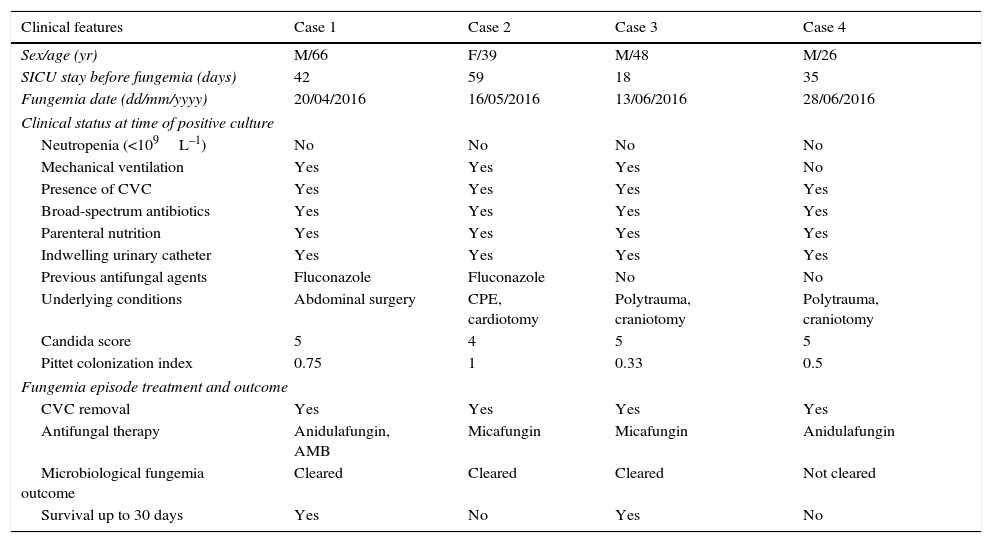

Results and discussionThe main clinical characteristics of the patients, the antifungal treatment administered and fungemia outcome are described in Table 1. All cases were observed between April and June 2016 in adult patients (26–66 years old) admitted to SICU, with an average length of stay before fungemia of 36 days (range, 18–59 days). All patients had been previously exposed to broad-spectrum antibiotics, parenteral nutrition and multiple invasive medical procedures including CVC, indwelling urinary catheter, and surgery, but none had neutropenia. Two patients received fluconazole before fungemia was diagnosed. Candida score was ≥4 in all patients at the onset of fungemia. Clinical management included catheter removal and prompt echinocandin therapy in all cases; in one case (Case 1) liposomal amphotericin B was administered concomitantly.

Main clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the patients.

| Clinical features | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex/age (yr) | M/66 | F/39 | M/48 | M/26 |

| SICU stay before fungemia (days) | 42 | 59 | 18 | 35 |

| Fungemia date (dd/mm/yyyy) | 20/04/2016 | 16/05/2016 | 13/06/2016 | 28/06/2016 |

| Clinical status at time of positive culture | ||||

| Neutropenia (<109L–1) | No | No | No | No |

| Mechanical ventilation | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Presence of CVC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parenteral nutrition | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Indwelling urinary catheter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Previous antifungal agents | Fluconazole | Fluconazole | No | No |

| Underlying conditions | Abdominal surgery | CPE, cardiotomy | Polytrauma, craniotomy | Polytrauma, craniotomy |

| Candida score | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Pittet colonization index | 0.75 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.5 |

| Fungemia episode treatment and outcome | ||||

| CVC removal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Antifungal therapy | Anidulafungin, AMB | Micafungin | Micafungin | Anidulafungin |

| Microbiological fungemia outcome | Cleared | Cleared | Cleared | Not cleared |

| Survival up to 30 days | Yes | No | Yes | No |

CPE, cardiogenic pulmonary edema; AMB, liposomal amphotericin B.

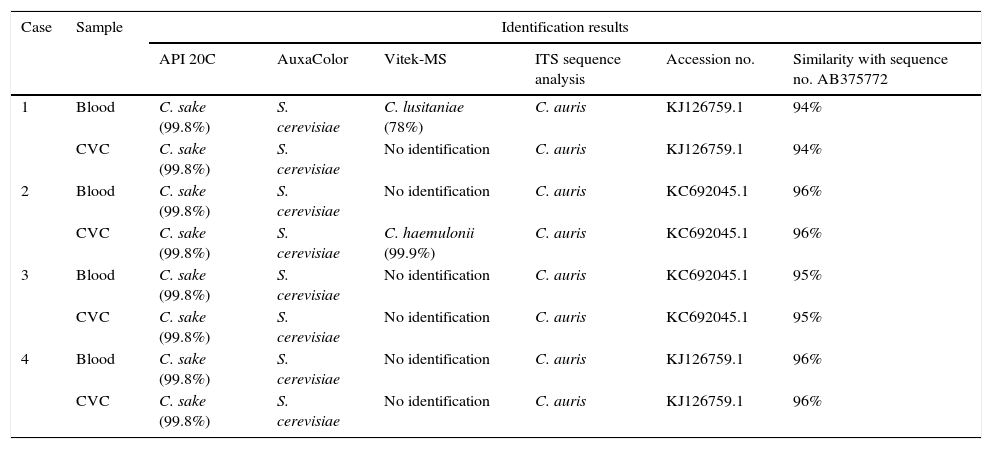

In all fungemia episodes yeast growth was detected in blood culture bottles after 7–32h incubation. In the quantitative CVC tips culture of the 4 patients a significant yeast growth was also obtained (>15CFU by the Maki technique and >100CFU by sonication). Subcultures on Sabouraud dextrose agar revealed smooth white to cream-colored colonies. All isolates grew well at 37°C, but not at 45°C or on Mycosel agar. In Chromagar Candida all isolates formed smooth pinkish, creamy colonies after 48h incubation. The identification of the isolates obtained by the different techniques are shown in Table 2. All isolates were initially identified as S. cerevisiae by AuxaColor 2 technique and as C. sake with the API ID20C yeast identification system. By means of VITEK MS technology, the blood isolate from patient 1 was identified as Candida lusitaniae and the CVC tip isolate from patient 2 as C. haemulonii; the other six isolates could not be identified by this technique. DNA identification, based on the ITS region sequences, classified all isolates as C. auris.

Results of identification testing for 8 isolates from 4 patients with C. auris fungemia.

| Case | Sample | Identification results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| API 20C | AuxaColor | Vitek-MS | ITS sequence analysis | Accession no. | Similarity with sequence no. AB375772 | ||

| 1 | Blood | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | C. lusitaniae (78%) | C. auris | KJ126759.1 | 94% |

| CVC | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | No identification | C. auris | KJ126759.1 | 94% | |

| 2 | Blood | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | No identification | C. auris | KC692045.1 | 96% |

| CVC | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | C. haemulonii (99.9%) | C. auris | KC692045.1 | 96% | |

| 3 | Blood | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | No identification | C. auris | KC692045.1 | 95% |

| CVC | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | No identification | C. auris | KC692045.1 | 95% | |

| 4 | Blood | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | No identification | C. auris | KJ126759.1 | 96% |

| CVC | C. sake (99.8%) | S. cerevisiae | No identification | C. auris | KJ126759.1 | 96% | |

CVC, central venous catheter.

The real burden of C. auris infections could be underestimated since this species is currently misidentified in the clinical laboratories by commercially available identification tests based on biochemical characteristics. Consequently, it is necessary to confirm the identification by DNA sequencing of all high fluconazole-resistant isolates of species usually susceptible to this antifungal agent.

Nowadays, two MALDI-TOF systems are commercially available for routine bacterial and fungal identification in the clinical microbiology laboratories: Vitek MS (bioMérieux) and MALDI Biotyper CA System (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). Vitek MS combines two software platforms: Vitek MS IVD for routine diagnosis (that not includes C. auris in its database), and Vitek MS Research Use Only (RUO) whose database has recently been implemented (May 2016) with the C. auris spectra only for research purposes.12 MALDI Biotyper CA System has a database library that contains spectra of 3 strains of C. auris, two from Korea and one from Japan.13 Usually, genomics studies include C. auris within the C. haemulonii complex due to striking similarities in biochemical characteristics; this may be the reason why C. auris is misidentified by Vitek MS.4,11 Furthermore, Chatterjee et al. have recently reported the first draft genome of C. auris to explore its genomic basis of virulence.6 The authors found that C. auris has a highly divergent genome and shares genes with C. albicans and C. lusitaniae, pointing out a common ancestry. These findings could explain the frequent misidentification of C. auris as C. lusitaniae using the MALDI-TOF databases.

The eight C. auris isolates showed the same antifungal MIC, independently of the sample or the patient. Fluconazole and voriconazole MICs were ≥256mg/l and 2mg/l, respectively, and those of the other antifungal agents ranged from ≤0.06mg/l of flucytosine to 0.5mg/l of amphotericin B. Although there are no defined breakpoints for this species, based on those established for other Candida species, our isolates were highly resistant to fluconazole and resistant to voriconazole, but susceptible to the other antifungals tested. Comparing these results with those reported by other authors, it seems that C. auris is a species which is globally resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole and susceptible to other antifungals, although resistance to echinocandins and amphotericin B has also been described.2,3,7,13,16 In our cases, it seems that there is no relationship between previous fluconazole treatment and C. auris fungemia, as only two patients received fluconazole before candidemia onset.

C. auris is an emerging cause of invasive candidiasis included within the C. haemulonii complex (Group II) based on physiological characteristics and isoenzimatic profile.4C. auris fungemia is associated with a high mortality rate, therapeutic failure, and widespread resistance to different antifungal agents.7,8,13,15–18 Outbreaks of nosocomial bloodstream infections by C. auris have been reported by other authors.3,7,8,16,17 In our series, the coexistence of four cases of fungemia by C. auris in a short period of time, in the same hospitalization unit, and with identical susceptibility pattern suggests a common source for all cases; to confirm this fact, we are currently conducting phylogenetic studies with all C. auris strains isolated in the SICU since the first fungemia episode caused by this species.

In conclusion, C. auris is an emerging pathogen that is underreported because it is misidentified in routine diagnostic laboratories. Furthermore, its resistance to fluconazole and other antifungal agents could make the management of deep-seated infections caused by this species difficult.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.