Invasive candidiasis is a leading cause of mortality. Candidaemia is the most common clinical presentation of invasive candidiasis but more that 30% of these infections do not yield positive blood cultures. Candida albicans remains the predominant aetiology, accounting for 50% of all cases. However, there has been an epidemiological shift in the last decades. Some species of Candida different to C. albicans have emerged as an important cause of severe candidaemia as they can exhibit resistance to fluconazole and other antifungal agents. Moreover, there is a different distribution of non C. albicans Candida species in relationship to patients’ and hospital characteristics. Thus, Candida parapsilosis has been associated to candidaemia in neonates and young adults. This species usually has an exogenously origin and contaminates medical devices, causing central venous catheter-associated candidaemias. Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei are isolated in blood cultures from older patients (>65 years) with important risk factors, such as major abdominal surgery, solid tumours and haematologic malignancies, transplants, and/or prolonged treatment with corticoids. Moreover, important geographical differences in the distribution of the Candida species different to C. albicans causing invasive candidiasis have been reported: C. parapsilosis predominates in Australia, Latin America and Mediterranean countries of Africa, Asia and Europe. In contrast, C. glabrata has an important aetiological role in USA and Central and Northern Europe. Finally, an important and worrying issue is that mortality due to invasive candidiasis remains unacceptably high.

This manuscript is part of the series of works presented at the “V International Workshop: Molecular genetic approaches to the study of human pathogenic fungi” (Oaxaca, Mexico, 2012).

La candidiasis invasiva es una causa destacada de mortalidad. Su presentación más habitual es la candidemia peroen más de un 30% de las candidiasis invasivas, los hemocultivos son negativos. Candida albicans continúa siendo el patógeno etiológico más frecuente de las candidiasis invasivas y alrededor del 50% de todos los aislamientos de hemocultivos corresponden a esta especie. Sin embargo, en las últimas décadas, se está observando un cambio epidemiológico, con un incremento notable de especies de Candida diferentes de C. albicans. Además, las candidemias causadas por esta última especie pueden ser más graves porque muchas de ellas son resistentes a fluconazol y otros fármacos antimicóticos. La distribución de las candidemias causadas por especies de Candida diferentes de C. albicans difiere según la población de pacientes estudiados y las características del hospital. Así, Candida parapsilosis causa candidemias en recién nacidos y adultos jóvenes. Esta especie suele tener un origen exógeno y contamina instrumental y diferentes dispositivos médicos, por lo que induce candidemia asociada a catéteres. Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis y Candida krusei se aíslan de hemocultivos de pacientes de mayor edad (>65 años) con importantes factores de riesgo subyacentes, como cirugía abdominal, tumores sólidos y neoplasias hematológicas, trasplantes o tratamientos prolongados con corticoesteroides. También se han descrito diferencias geográficas importantes en la distribución de las especies de Candida diferentes de C. albicans causantes de candidiasis invasiva: C. parapsilosis predomina en Australia, América Latina y los países de la cuenca mediterránea de África, Asia y Europa. Por el contrario, C. glabrata desempeña un sustancial papel etiológico en los Estados Unidos y en los países nórdicos y de Europa central. Por último, un aspecto muy importante y preocupante es que la mortalidad atribuida a la candidiasis invasiva sigue siendo inaceptablemente alta.

Este manuscrito forma parte de la serie de artículos presentados en el «V International Workshop: Molecular genetic approaches to the study of human pathogenic fungi» (Oaxaca, México, 2012).

Invasive candidiasis is a severe infection that causes high morbidity and mortality. Candidaemia is the commonest presentation of invasive candidiasis, but it represents less than 75% of all invasive candidiasis. These invasive mycoses are mainly hospital-acquired infections and approximately two-thirds of them have their origin in different hospital wards. In recent years, community invasive candidiasis is raising in association to an increase of at home healthcare.21,66 Hajjeh et al.29 observed in a population-based study that 36% of candidaemia occurred in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and a third of them were of community onset. Wenzel and Edmond65 estimated that 5% of the patients admitted to tertiary hospitals will be affected by a nosocomial infection; a 10% of them will suffer from bloodstream infections (BSI), being 8–10% of these BSI caused by Candida. Since the 1980s, Candida is the fourth most common cause of BSI in USA and Europe, accounting for >85% of all fungaemias.56,61

Most studies have reported a steady increase in the rate of invasive candidiasis until 1990 that was remarkably consistent until 2003 (from 8 to 10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants). The current incidence of invasive candidiasis has remained similar in the last years or even has decreased slightly in Australia, Canada, Europe and USA. However, incidence is continuously growing in Latin America and the rest of the world (Tables 1 and 2). The incidence of candidaemia in Australia, Canada, Europe, and Latin America is significantly lower than in the USA. Incidences of 6–10 per 100,000 inhabitants have been reported in most population-based studies in the USA.21,22,30 In contrast, most European surveys show incidences of 1.4–5.7 per 100,000 inhabitants.3,7,8,46,63 However, there are two notable exceptions: Denmark and, most recently, Spain, where the incidence of invasive candidiasis is higher than in other European countries.1,4–6 Most Nordic countries have reported candidaemia in the range of 1.4–5.7 per 100,000 inhabitants, with more than 70% of them caused by Candida albicans.7,8,53,54,59 Candidaemia rates in Australia (1.8 invasive candidiasis per 100,000) and Canada (2.9 per 100,000) are similar to European ones.13,33

Selected population-based epidemiological studies on candidaemia and invasive candidiasis.

| Location | Year | Incidence (no. of cases/100,000 inhabitants/year) | References | ||

| Total | Children <1 year old | Patients ≥65 years old | |||

| America | |||||

| Canada | 1999–2004 | 2.9 | 20 | 21.3 | 33 |

| USA | 1992–1993 | 8 | 70 (Black: 165 vs. white 41) | 26 (Black: 40 vs. white 10) | 30 |

| USA | 1998–2001 | 6 | 22 | ||

| USA | 1998–2000 | 10 (7–24) | Black: 157 vs. white: 33 | Black (92) vs. white (30) | 29 |

| Europe | |||||

| Denmark | 2004–2006 | 10.4 | 16.3 | 36.9 | 6 |

| Denmark | 2004–2009 | 8.6 | 11.3 | 27.7 | 4 |

| Finland | 1995–1999 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 5.2 | 54 |

| Finland | 2004–2007 | 2.86 | 6.9 | 12.2 | 53 |

| Iceland | 1980–1989 | 1.4 | 12.7 | 7 | |

| Iceland | 1990–1999 | 4.9 | 11.3 | 19.3 | 7 |

| Iceland | 2000–2011 | 5.7 | 20.7 | 18.1 | 8 |

| Norway | 1991–2003 | 2.4 | 10.3 | 7 | 59 |

| Spain | 2002–2003 | 4.3 | 38.8 | 12 | 3 |

| Spain | 2010–2011 | 8.14 | 96.4 | 25 | 1 |

| Scotland (UK) | 2005–2006 | 4.8 | 55.9 | 46 | |

| Oceania | |||||

| Australia | 2001–2004 | 1.8 | 24.8 | 13.7 | 13 |

Selected epidemiological studies on candidaemia and invasive candidiasis.

| Location | Year | Incidence (no. of cases/1000 admissions/year) | References |

| America | |||

| Argentina | 2005–2008 | 1.15 (0.35–2.65) | 38 |

| Brazil | 1997–2007 | 0.74 (0.41–1.21) | 58 |

| Brazil | 2006–2010 | 0.54 (0.41–0.71) | 16 |

| International | 2010 | 1.18 (0.33–1.96) | 44 |

| USA | 1998–2000 | 0.15 | 29 |

| Asia | |||

| China | 1998–2007 | 0.026 | 67 |

| Taiwan | 2000–2010 | 0.351 | 32 |

| Europe | |||

| Austria | 2001–2006 | 0.27–0.77 | 55 |

| Denmark | 2004–2006 | 0.51 | 6 |

| Denmark | 2004–2009 | 0.41 | 4 |

| England (UK) | 2005–2008 | 0.11 | 20 |

| Germany | 1998–2008 | 0.47 | 64 |

| Iceland | 1980–1989 | 0.15 | 7 |

| Iceland | 1990–1999 | 0.55 | 7 |

| International | 1997–1999 | 0.20–0.38 | 62 |

| Scotland (UK) | 2005–2008 | 0.59 | 46 |

| Spain | 2002–2003 | 0.53 | 3 |

| Spain | 2008–2009 | 1.09 | 14 |

| Spain | 2010 | 0.92 | 47 |

| Spain | 2010–2011 | 0.90 | 1 |

| Oceania | |||

| Australia | 2001–2004 | 0.21 | 13 |

| Australia | 1999–2008 | 0.45 | 52 |

Although the epidemiology of candidaemia in Latin America has not been studied so deeply, a recent prospective laboratory-based survey in 22 hospitals from 8 Latin American countries showed an incidence of 0.98 episodes per 1000 hospital admissions. In spite of being broad variations among countries (0.33 in Chile versus 1.96 episodes per 1000 hospital admissions in Argentina and Colombia), the mean incidence was higher than those reported in USA (0.28–0.96 episodes per 1000 hospital admissions) or Europe (0.2–0.38 episodes per 1000 hospital admissions).44,45 There is not a clear reason of these higher rates of invasive candidiasis in Latin America, USA, Denmark or Spain, but the different rates of sampling, distribution of risk factors in the populations studied, the age distribution, or in the study methodologies, can contribute.1,6,33

Of interest, the highest incidences of invasive candidiasis occur in males (60%), at age extremes (infants <1 year and adults >65 years’ old: circa 16 episodes and circa 36 episodes per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively), in cancer (71 episodes per 100,000), and diabetic patients (28 episodes per 100,000).1–3,29,30 Cancer is a very frequent underlying disease in patients suffering from candidaemia but there are differences among cancer patients. In those patients with haematological malignancies, chemotherapy and the consequent neutropaenia, digestive tract mucositis and treatment with corticoids are added risk factors for invasive candidiasis. By comparison, in patients with solid tumours, candidaemia is associated to complications of surgery, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, hyperalimentation and presence of central venous catheters.10 These rates are particularly high in surgical, trauma and burn units, and neonatal ICUs. A recent SENTRY study reported a total of 1752 Candida isolates distributed nearly equal from invasive ICU and non-ICU settings. The frequency of ICU-associated candidaemia was also higher in Latin America (56.5%) compared with Europe (44.4%) and USA (39.6%).50,56,66

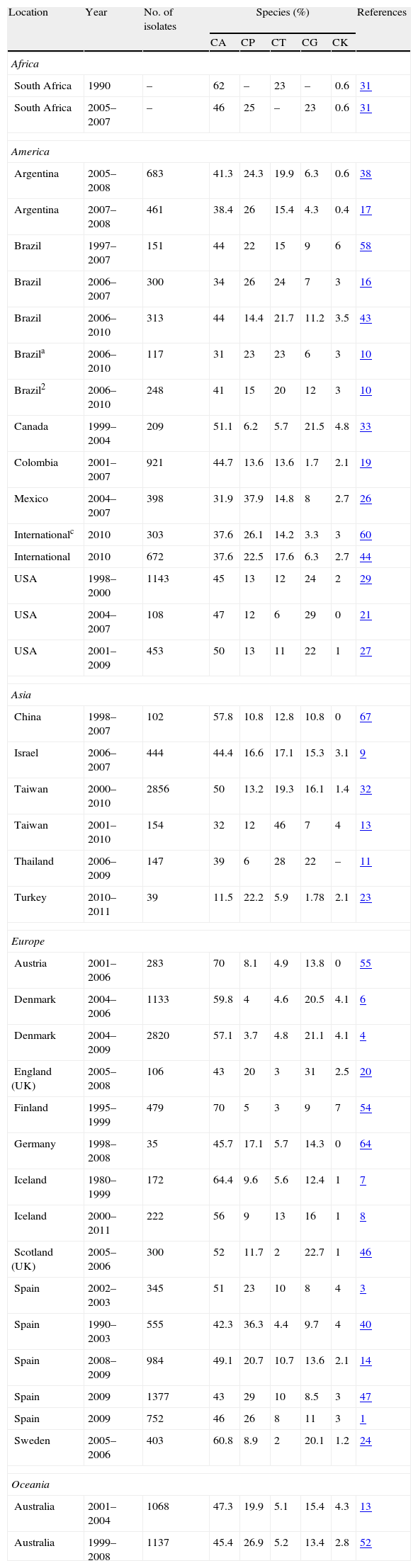

Role of different species of Candida in the aetiology of candidaemiaDuring the past decades, most hospitals have reported an important and progressive shift in the aetiology of invasive candidiasis in different groups of patients and distinct hospital settings. Nevertheless, C. albicans remains the predominant species in most studies, with incidences ranging from 11.5% in Turkey or 32% in Mexico and Taiwan to more than 60% in Austria and Sweden (Table 3). The reasons of this shift are not completely understood but several factors have been associated with candidaemia depending on the implicated species. In the 2008–2009 SENTRY study including Candida isolates from 79 medical centres, approximately 90–95% of isolates belonged to five species: C. albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei.50 However, the distribution of C. albicans and non-C. albicans Candida species causing candidaemia vary enormously between hospitals and patients with a significant increase in those invasive candidiasis caused by Candida different to C. albicans.15,16,28,36,37,63 An interesting feature of the latter is a patient-specificity and a particular geographical distribution (Fig. 1 and Table 3). Moreover, other important feature of some Candida different to C. albicans, such as C. glabrata and C. krusei, is their lower susceptibility to fluconazole and other antifungal agents.3,4,36,41,42,49–52 These characteristics can complicate the therapeutic approach of candidaemia caused by these Candida species. The attributable mortality rate of candidaemia is estimated to be >30%, with a crude mortality rate of >50%. This mortality exceeds widely the one reported for most bacterial infections. Since 1989, a 50% reduction in mortality rates for invasive candidiasis has been reported, following a steady increase in mortality in the previous decades reaching 0.62 deaths per 100,000 persons. A similar decline in rates of death from invasive candidiasis associated with HIV infection occurred (0.04 per 100,000). The explanation for decreased mortality in both HIV infected and non-infected patients could be related to the increased awareness, earlier diagnosis, and the enhanced therapy of candidaemias. Furthermore, candidaemia not only increases patient mortality, but also extends the length of stay and increases the total cost of medical care. Patient outcomes appear to be worst for candidaemia due to Candida different to C. albicans, mainly caused by C. glabrata and C. tropicalis, and to a lesser extent C. krusei. However, infections due to C. parapsilosis tend to be associated with reduced lethality (23%).1,41,42

Distribution of the five most frequent species of Candida on selected epidemiological studies on candidaemia and invasive candidiasis.

| Location | Year | No. of isolates | Species (%) | References | ||||

| CA | CP | CT | CG | CK | ||||

| Africa | ||||||||

| South Africa | 1990 | – | 62 | – | 23 | – | 0.6 | 31 |

| South Africa | 2005–2007 | – | 46 | 25 | – | 23 | 0.6 | 31 |

| America | ||||||||

| Argentina | 2005–2008 | 683 | 41.3 | 24.3 | 19.9 | 6.3 | 0.6 | 38 |

| Argentina | 2007–2008 | 461 | 38.4 | 26 | 15.4 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 17 |

| Brazil | 1997–2007 | 151 | 44 | 22 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 58 |

| Brazil | 2006–2007 | 300 | 34 | 26 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 16 |

| Brazil | 2006–2010 | 313 | 44 | 14.4 | 21.7 | 11.2 | 3.5 | 43 |

| Brazila | 2006–2010 | 117 | 31 | 23 | 23 | 6 | 3 | 10 |

| Brazil2 | 2006–2010 | 248 | 41 | 15 | 20 | 12 | 3 | 10 |

| Canada | 1999–2004 | 209 | 51.1 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 21.5 | 4.8 | 33 |

| Colombia | 2001–2007 | 921 | 44.7 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 19 |

| Mexico | 2004–2007 | 398 | 31.9 | 37.9 | 14.8 | 8 | 2.7 | 26 |

| Internationalc | 2010 | 303 | 37.6 | 26.1 | 14.2 | 3.3 | 3 | 60 |

| International | 2010 | 672 | 37.6 | 22.5 | 17.6 | 6.3 | 2.7 | 44 |

| USA | 1998–2000 | 1143 | 45 | 13 | 12 | 24 | 2 | 29 |

| USA | 2004–2007 | 108 | 47 | 12 | 6 | 29 | 0 | 21 |

| USA | 2001–2009 | 453 | 50 | 13 | 11 | 22 | 1 | 27 |

| Asia | ||||||||

| China | 1998–2007 | 102 | 57.8 | 10.8 | 12.8 | 10.8 | 0 | 67 |

| Israel | 2006–2007 | 444 | 44.4 | 16.6 | 17.1 | 15.3 | 3.1 | 9 |

| Taiwan | 2000–2010 | 2856 | 50 | 13.2 | 19.3 | 16.1 | 1.4 | 32 |

| Taiwan | 2001–2010 | 154 | 32 | 12 | 46 | 7 | 4 | 13 |

| Thailand | 2006–2009 | 147 | 39 | 6 | 28 | 22 | – | 11 |

| Turkey | 2010–2011 | 39 | 11.5 | 22.2 | 5.9 | 1.78 | 2.1 | 23 |

| Europe | ||||||||

| Austria | 2001–2006 | 283 | 70 | 8.1 | 4.9 | 13.8 | 0 | 55 |

| Denmark | 2004–2006 | 1133 | 59.8 | 4 | 4.6 | 20.5 | 4.1 | 6 |

| Denmark | 2004–2009 | 2820 | 57.1 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 21.1 | 4.1 | 4 |

| England (UK) | 2005–2008 | 106 | 43 | 20 | 3 | 31 | 2.5 | 20 |

| Finland | 1995–1999 | 479 | 70 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 54 |

| Germany | 1998–2008 | 35 | 45.7 | 17.1 | 5.7 | 14.3 | 0 | 64 |

| Iceland | 1980–1999 | 172 | 64.4 | 9.6 | 5.6 | 12.4 | 1 | 7 |

| Iceland | 2000–2011 | 222 | 56 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 1 | 8 |

| Scotland (UK) | 2005–2006 | 300 | 52 | 11.7 | 2 | 22.7 | 1 | 46 |

| Spain | 2002–2003 | 345 | 51 | 23 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Spain | 1990–2003 | 555 | 42.3 | 36.3 | 4.4 | 9.7 | 4 | 40 |

| Spain | 2008–2009 | 984 | 49.1 | 20.7 | 10.7 | 13.6 | 2.1 | 14 |

| Spain | 2009 | 1377 | 43 | 29 | 10 | 8.5 | 3 | 47 |

| Spain | 2009 | 752 | 46 | 26 | 8 | 11 | 3 | 1 |

| Sweden | 2005–2006 | 403 | 60.8 | 8.9 | 2 | 20.1 | 1.2 | 24 |

| Oceania | ||||||||

| Australia | 2001–2004 | 1068 | 47.3 | 19.9 | 5.1 | 15.4 | 4.3 | 13 |

| Australia | 1999–2008 | 1137 | 45.4 | 26.9 | 5.2 | 13.4 | 2.8 | 52 |

Candidaemia in patients with haematological malignancies1 or solid tumours2. 3Candidaemia in children from 8 Latin American countries. CA=Candida albicans, CP=Candida parapsilosis, CT=Candida tropicalis, CG=Candida glabrata, and CK=Candida krusei.

C. parapsilosis is acquired from an exogenous source and is primarily isolated from cancer patients, and young adults and neonates in ICUs, usually in association to colonisation of central venous catheters and parenteral nutrition. This species predominates in candidaemias reported from Australia, Latin America and the Mediterranean countries of Africa, Asia and Europe. C. parapsilosis is usually susceptible to most antifungal agents, but there are reports of clinical isolates with decreased susceptibility to azoles and echinocandins.1–3,10–16,23–26,38,40,43–48,52,60

C. glabrata and C. krusei are associated with recent major abdominal surgery, solid tumours, old patients (>65 years), neutropaenic neonates, transplant recipients, and patients treated with corticoids.1,10,45,48,60C. glabrata predominates as second cause of candidaemia in USA and the countries of the North and Centre of Europe.4–8,20,55 The proportion of C. glabrata has remained constant worldwide at 9–12% but C. glabrata is more common in USA (21.1%) than in the rest of the world (7.6–12.6%).15,47–49 Some authors have linked institutional or individual fluconazole use to the selection of C. glabrata, especially in cancer centres.28,35,51,56,57 In a recent SENTRY study, including 79 medical centres and a total of 1752 Candida isolates, C. glabrata was the only species in which resistance to azoles and echinocandins was reported.50 Of interest, candidaemia due to C. glabrata and C. krusei is relatively low in Latin America, and the fluconazole resistance rates of clinical isolates of C. glabrata are lower (10–13%) than in USA (18–20%).44,45 However, in Brazil a significant increase of C. glabrata blood isolates from the 1995–2003 period to the 2005–2007 period was observed, mainly in hospitals with higher use of fluconazole in the treatment of invasive candidiasis.15 In Northern European countries, C. dubliniensis, a species close-related to C. albicans, can exceed 2–3% of blood isolates.4,8,46 Finally, C. tropicalis has been isolated from patients with solid tumours or haematologic diseases and it has been reported as the second etiological agent of invasive candidiasis in Asia and some parts of Latin America (Colombia and Brazil). The overrepresentation of C. tropicalis candidaemia in patients aged >70 years can be related to the increased frequency of solid tumours and haematologic malignancies in the elderly population.32,34,43,67 Multi-fungal infections do not exceed 5% of candidaemias, being C. albicans the species most frequently isolated in combination with other yeasts, with C. glabrata and C. tropicalis accounting for the majority of episodes.6

Two of these emerging species, C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata are in fact complexes of species with special clinical and demographic characteristics.12,18,40C. parapsilosis includes 3 different species: Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto, Candida metapsilosis and Candida orthopsilosis, but the real importance of C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis as human pathogens remains unknown. In a recent Spanish nationwide study, the incidence of episodes of candidaemia due to C. parapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis were 0.22 and 0.02 per 1000 admissions, respectively. C. orthopsilosis was the fifth most frequently isolated species, preceding C. krusei (0.018 episodes per 1000 admissions).47,48 The prevalence of C. orthopsilosis is apparently higher in warmer Mediterranean countries than in the cooler countries of the Atlantic, Central and North Europe. A higher prevalence of C. orthopsilosis has also been reported in countries with hot and humid climates, such as Taiwan (8.5%), Brazil (9.1%) and Malaysia (24.4%). However, other factors could be responsible for local specificities, such as differences in hospital services (presence or absence of ICU or surgical wards) and the patient population (transplant recipients and other immunodeficient patients).40C. glabrata complex includes C. glabrata sensu stricto and two newly described species, Candida bracarensis and Candida nivariensis.18,39 Lockhart et al.37, in their analysis of 1598 C. glabrata isolates from 29 countries, observed that C. bracarensis and C. nivariensis isolates constituted a very small percentage (0.2%) of the C. glabrata clinical isolates. However, these cryptic species could be more prevalent in specific regions. Most reports have underlined the lower susceptibility of C. bracarensis and C. nivariensis to the most commonly used azoles.

ConclusionsInvasive candidiasis is a leading cause of mortality worldwide. C. albicans remains the predominant cause of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis, accounting for 50% of all cases. However, an evident shift has been reported in the epidemiology, as some Candida species different to C. albicans have emerged as cause of candidaemia and can exhibit resistance to fluconazole and other triazoles, echinocandins and/or amphotericin B. C. parapsilosis is associated to infections in neonates and young adults, usually related to the presence of central venous catheter and hyperalimentation. C. glabrata, C. tropicalis and C. krusei cause infections in older patients in association to recent major abdominal surgery, solid tumours, transplants, and/or prolonged treatment with corticoids. Moreover, there are some important geographical differences in the distribution of those Candida species different to C. albicans causing invasive candidiasis. C. parapsilosis is the first or second aetiology of candidaemia in Australia, Latin America and Mediterranean countries of Africa, Asia and Europe. Conversely, C. glabrata has an important aetiological role in USA and Central and Northern Europe. Finally, an important and worrying issue is that mortality due to invasive candidiasis remains unacceptably high.

Conflict of interestIn the past 5 years, GQA has received grant support from Astellas Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, Schering Plough and Merck Sharp and Dohme. He has been an advisor/consultant to Merck Sharp and Dohme, and has been paid for talks on behalf of Astellas Pharma, Esteve Hospital, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, and Schering Plough.

GQA has received grant support from Consejería de Educación, Universidades e Investigación (GIC12 210-IT-696-13) and Departamento de Industria, Comercio y Turismo (S-PR12UN002, S-PR11UN003) of Gobierno Vasco-Eusko Jaurlaritza, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS PI11/00203), and Universidad del País Vasco-Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UFI 11/25, UPV/EHU).