Surgical delay for hip fractures (>48h) has been associated with greater adverse clinical events. However, the influence of the reasons for delay is unclear. The objective of this study was to analyse the causes of surgical delay and its influence on morbidity and mortality, in patients with hip fracture with indication for surgical treatment.

Material and methodA cohort of 376 hip fractures operated at our centre between January 2012 and December 2016 was retrospectively reviewed. Patients younger than 65 years and pathological fractures were excluded. Of these, 280 patients were operated with a surgical delay >48h. The causes of the delay were: antiaggregation (AG), anticoagulation (AC), medical reasons (MM), preoperative cardiac tests or administrative/organisational reasons. Surgical wound complications, general complications and mortality were compared.

ResultsThere was a greater proportion of surgical wound complications in the AC group (p=.063). Patients in the AG, AC, and MM groups had higher rates of general associated complications (p=.3). Seven point fifty-one percent of the patients included died one year after surgery. The mortality rate at one year was highest in the MM group (p=.005).

ConclusionThe mortality rate was statistically significantly higher in the MM group. When comparing results, patients in the AG, AC, and MM groups presented higher rates of general complications.

El tratamiento quirúrgico demorado en fracturas de cadera (>48h) se ha asociado con una mayor frecuencia de eventos clínicos adversos. Sin embargo, no está clara la influencia de los motivos de demora en estos resultados. El objetivo de este estudio es el análisis de las causas de demora quirúrgica y su influencia en la morbimortalidad en pacientes con fractura de cadera con indicación de tratamiento quirúrgico.

Material y métodoSe revisó retrospectivamente una cohorte de 376 fracturas de cadera intervenidas en nuestro centro entre enero de 2012 y diciembre de 2016. Se excluyó a pacientes menores de 65 años y fracturas patológicas. De ellos, 280 pacientes fueron intervenidos con una demora quirúrgica de >48h. Las causas de la demora fueron: antiagregación (AG), anticoagulación (AC), motivos médicos (MM), test cardíacos preoperatorios o motivos administrativos/organizativos. Se compararon las complicaciones de la herida quirúrgica, las complicaciones generales y la mortalidad.

ResultadosHubo una mayor proporción de complicaciones de la herida quirúrgica en los AC (p=0,063). Los pacientes de los grupos AG, AC y MM se asociaron a mayores tasas de complicaciones generales (p=0,3). El 7,51% de los pacientes incluidos falleció al año de la cirugía. La tasa de mortalidad al año fue mayor en el grupo MM (p=0,005).

ConclusiónLa tasa de mortalidad fue mayor de forma estadísticamente significativa en el grupo MM. Al comparar resultados, los pacientes de los grupos AG, AC y MM presentaron mayores tasas de complicaciones generales.

The rate of hip fractures in the elderly has continuously risen in the last few decades. These are usually patients subjected to frequent medical changes where these lesions have a great impact on their quality of life and functional recovery.1

Determining the best time to operate is of vital importance to improve the outcomes of this type of fracture. In 2011 the Spanish Orthopaedic and Traumatology Society (SECOT), through the Study and Research Group on Osteoporosis (GEIOS),2 indicated that the treatment of choice was surgery which was to be performed as quickly as possible. The National Health System in Spain establishes hip fracture surgery in the first 48h of hospital admission as the indicator of care quality. However, the percentage of patients with a hip fracture who underwent surgery during the first 48h in our environment is relatively low, between 24% and 44%, according to published series.3–5

Surgical delay may be due to several factors, including the “weekend” effect or delay associated with admission during the weekend or public holidays; taking anticoagulation or antiaggregant medication associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality a year after surgery; the need to carry out preoperative cardiac tests and/or the need to stabilise medical comorbidities or imbalances on admission.6

Some studies examine the previously mentioned factors and their influence on morbidity and mortality on an individual basis. For example in 2010, Sánchez-Crespo et al. in a series of 636 hip fractures, found a higher rate of mortality associated with the “admission day” factor as a reason for surgical delay.5 Furthermore, in 2017, Lawrence et al., analysed a series of 2036 hip fractures in anticoagulated patients, and observed lower survival rates in them, without bearing in mind the waiting time prior to surgery.7 However, the impact of these factors in morbidity and mortality of patients with hip fracture in delayed procedures has not yet been analysed.7,8

The aim of this study was to analyse the causes for surgical delay and its impact on hip fracture patient morbidity and mortality where indication was for surgical treatment.

Material and methodsAn analytical observational cohort study was conducted, for which patients over 65 years of age with proximal fracture of the femur were analysed between January 2012 and December 2016, recorded in our database. We recorded a total of 376 fractures operated on in our centre, after excluding those who had been operated on during the first 48h, pathological fractures and fractures in polytraumatised patients.

Two hundred and eighty fractures which had been operated on 48h after admission were included in the study. The surgical delay was considered to be the number of days passing from admission until the surgery. The patient cohorts were defined according to the reasons for delay: for administrative or organisational reasons [AA, admission on a public holiday, weekend or Thursday]; anticoagulation (AC); antiaggregation (AG) which required removal according to Anaesthesia Service criteria; medical destabilisation caused by associated comorbidities (MM; which required prior stabilisation by internal physicians or anaesthesiologists) and prior cardiac tests (CT) requested during pre-anaesthesia assessment. For example, an echocardiography in patients with known cardiopathy reviewed over 6 months previously.

On admission the following were recorded: age, sex, weight, height, day of the week of admission. From the analysis on admission the values of lactate, leukocytes, lymphocytes <1.5 were recorded, in addition to serum creatinine, and calculation of the creatinine clarification using the Cockcroft–Gault formula was made.9 Administration of anticoagulant medication or antiaggregant medication was also recorded. The associated comorbidities recorded were: diabetes mellitus, rheumatologic diseases, transplant, treatment with corticoids, hepatopathy, alcoholism. Cognitive state was determined by anamnesis and clinical examination, determining the presence or absence of dementia. The level of deambulation and Independence for daily life activities was assessed using the Barthel scale scores.8

On their admission to the emergency services the patient was initially assessed by the emergency service physician and later by the orthopaedic surgeon. After confirmation of diagnosis using radiological study, a complete preoperative study was made, consisting of a complete analysis: biochemical study, coagulation haemogram, posteroanterior chest X-ray, electrocardiogram. After medication adjustment the patient was taken to the ward and the consultation sheet was drawn up for presurgical screening by the anaesthesia service. The surgical technique used depended on the type of fracture: partial or total hip replacement in patients with displaced subcapital fracture; intramedullary nailing in petrochanteric and subtrochanteric fracture. The patients were anaesthetised using spinal or general anaesthesia, following the criteria of the anaesthetist participating in the operation. Antibiotic prophylaxis following the protocol proposed by the Commission of Infectious diseases and antithrombotic prophylaxis was adjusted according to renal clearance. A control analysis was requested 24h after surgery. In the cases where the patient was classified as ASA 4, a prolonged resuscitation bed was reserved. Seating of the patient was authorised 24h later and walking with the assistance of a walker or crutches thereafter. When the patient was fully stabilised they were discharged from hospital.

During hospital stay the following were recorded: the need for transfusion, surgical wound complications (seroma, haematoma or prolonged weeping and/or infection of the surgical wound) and general complications (agitation or confusional syndrome, chronic decompensated heart failure, urinary tract infection, acute renal failure, pneumonia, anaemia, digestive problems, bed ulcers, deep vein thrombosis, fever). Death rates were also recorded, during the first month after surgery and one year after surgery.

The differences between the groups were analysed with regard to the presence of variables, modifiers of effect or confusing modifiers, which could have an influence on the proportion of wound complications and general complications, and also mortality.

Essential variables analysed were: age, sex, the Barthel index, dementia on admission, lymphopenia, the presence of comorbidities and variables relating to the patient. Also, the type of fracture and type of surgery, ASA classification, prolonged resuscitation and the need for transfusion or variables relating to surgery.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS programme version 20.0. Comorbidities, the presence of dementia and lymphopenia were adjusted as dichotomist qualitative variables with the presence and absence of the same. Continuous, quantitative variables of age and Barthel index were transformed: age was dichotomised in patients over or under 83 years of age, depending on the median and the Barthel index was stratified into levels of dependence depending on score: mild if the score was between 91 and 99, moderate if it was between 61 and 90 and severe if it was under 60 points. The type of fracture variable was dichotomised into intracapsular and extracapsular. Contrast we carried out using the Chi squared test with Yates correction as required. The differences between the groups were analysed according to the proportion of the before-mentioned essential variables. After this, we proceeded to do a bivariate analysis, to analyse the dependent variables ratio: wound complications, general complications and death, with each of the cohorts compared with the delay group. Significance was considered to be a p value of ≤.05.

Results280 fractures were included in the study, all of which had been operated on 48h after admission. The mean age of patients was 82.7 years. There were 212 women (75.7%). The most common fracture type was extracapsular (189 patients; 67.5%).

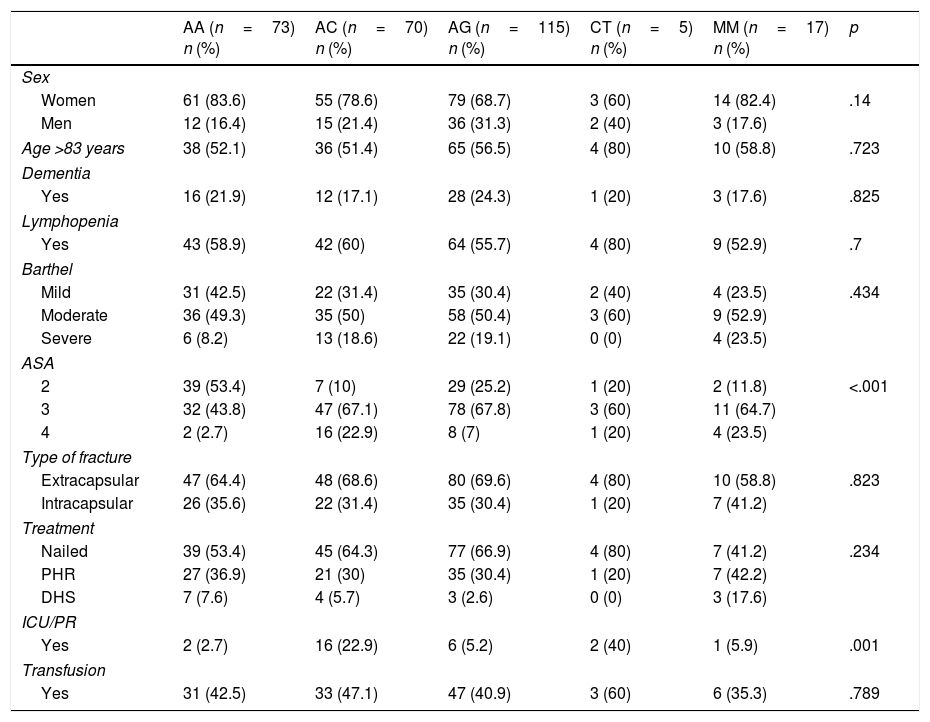

Mean surgical delay was 4.52 days (SD 2.19; range from 3 to 17). Of the patients who were admitted to hospital, 31% were operated on 3 days after admission; 38% after 4 days; 13% after 5 days; 8% after 6 days and 6% 7 days after admission. The patient cohorts were distributed depending on the cause of the delay to surgery which was: AA in 73 patients, AC in 70, AG in 115, MM in 17 and CT in 5 patients. The confusing variables analysed distributed by cause for delay are contained in Table 1.

Description of the characteristics of the 5 groups according to the cause of the delay to surgery.

| AA (n=73) n (%) | AC (n=70) n (%) | AG (n=115) n (%) | CT (n=5) n (%) | MM (n=17) n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 61 (83.6) | 55 (78.6) | 79 (68.7) | 3 (60) | 14 (82.4) | .14 |

| Men | 12 (16.4) | 15 (21.4) | 36 (31.3) | 2 (40) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Age >83 years | 38 (52.1) | 36 (51.4) | 65 (56.5) | 4 (80) | 10 (58.8) | .723 |

| Dementia | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (21.9) | 12 (17.1) | 28 (24.3) | 1 (20) | 3 (17.6) | .825 |

| Lymphopenia | ||||||

| Yes | 43 (58.9) | 42 (60) | 64 (55.7) | 4 (80) | 9 (52.9) | .7 |

| Barthel | ||||||

| Mild | 31 (42.5) | 22 (31.4) | 35 (30.4) | 2 (40) | 4 (23.5) | .434 |

| Moderate | 36 (49.3) | 35 (50) | 58 (50.4) | 3 (60) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Severe | 6 (8.2) | 13 (18.6) | 22 (19.1) | 0 (0) | 4 (23.5) | |

| ASA | ||||||

| 2 | 39 (53.4) | 7 (10) | 29 (25.2) | 1 (20) | 2 (11.8) | <.001 |

| 3 | 32 (43.8) | 47 (67.1) | 78 (67.8) | 3 (60) | 11 (64.7) | |

| 4 | 2 (2.7) | 16 (22.9) | 8 (7) | 1 (20) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Type of fracture | ||||||

| Extracapsular | 47 (64.4) | 48 (68.6) | 80 (69.6) | 4 (80) | 10 (58.8) | .823 |

| Intracapsular | 26 (35.6) | 22 (31.4) | 35 (30.4) | 1 (20) | 7 (41.2) | |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Nailed | 39 (53.4) | 45 (64.3) | 77 (66.9) | 4 (80) | 7 (41.2) | .234 |

| PHR | 27 (36.9) | 21 (30) | 35 (30.4) | 1 (20) | 7 (42.2) | |

| DHS | 7 (7.6) | 4 (5.7) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (17.6) | |

| ICU/PR | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (2.7) | 16 (22.9) | 6 (5.2) | 2 (40) | 1 (5.9) | .001 |

| Transfusion | ||||||

| Yes | 31 (42.5) | 33 (47.1) | 47 (40.9) | 3 (60) | 6 (35.3) | .789 |

AA: administrative reasons group; AC: anticoagulated group; AG: antiaggregated group; DHS: DHS®nailed plate; MM: group with medical imbalances on admission; PHR: partial hip replacement; RP: prolonged resuscitation; CT: pre-operative cardiac tests; ICU: intensive care unit.

There were no differences with regard to distribution by sex and proportion of patients over 83 between the groups. With regard to the presence of comorbidities, lymphopenia (indirect sign of malnutrition), diabetes, HBP and dementia were the most prevalent: lymphopenia in 162 patients (57.8%), HBP in 114 cases (34%), diabetes in 83 cases (30%) and dementia in 60 patients (21.4%). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups.

With regard to the Barthel scale scores, we recorded a higher proportion of patients with a mild degree in the group of patients delayed by AA, with 42.5%, whilst in the group of patients delayed by MM we recorded a higher proportion of patients with a severe degree, with 23.5% (p=.434).

Over half of the patient group delayed by AA were ASA 2 (53 4%) (p<.001). In the patient groups of AC, AG, MM and CT a greater proportion of ASA 3 were recorded, with scores of 67.1%, 67.8%, 64.7% and 60%, respectively. The AC and CT patients required a prolonged resuscitation time to a higher degree, 22.9% and 40%, respectively (p=.001).

Regarding fracture type, we observed that extracapsular are the most frequent in all groups, although the proportion of intracapsular fractures is higher in the cohort studies of medical morbidities (41.2%) (p=.823) (Table 1).

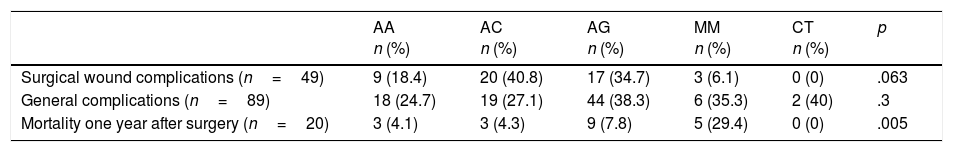

With regard to morbidity and mortality, on the understanding that morbidity is the presence of general complication and/or of surgical wound, these are present in Table 2 and specified in Tables 3 and 4.

Surgical wound complications, general complications and mortality asked with surgical delay.

| AA n (%) | AC n (%) | AG n (%) | MM n (%) | CT n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical wound complications (n=49) | 9 (18.4) | 20 (40.8) | 17 (34.7) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) | .063 |

| General complications (n=89) | 18 (24.7) | 19 (27.1) | 44 (38.3) | 6 (35.3) | 2 (40) | .3 |

| Mortality one year after surgery (n=20) | 3 (4.1) | 3 (4.3) | 9 (7.8) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0) | .005 |

AA: administrative reasons group; AC: anticoagulated group; AG: antiaggregated group; MM: group with medical imbalances on admission; CT: pre-operative cardiac tests.

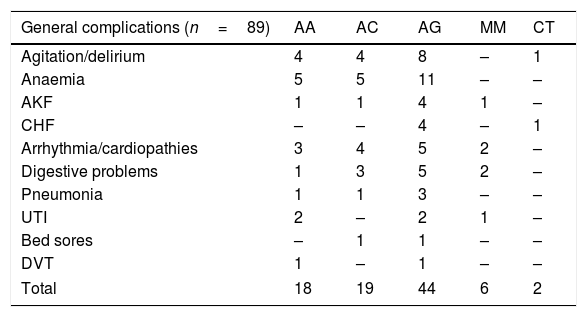

Description of general complications.

| General complications (n=89) | AA | AC | AG | MM | CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agitation/delirium | 4 | 4 | 8 | – | 1 |

| Anaemia | 5 | 5 | 11 | – | – |

| AKF | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | – |

| CHF | – | – | 4 | – | 1 |

| Arrhythmia/cardiopathies | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | – |

| Digestive problems | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | – |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 1 | 3 | – | – |

| UTI | 2 | – | 2 | 1 | – |

| Bed sores | – | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| DVT | 1 | – | 1 | – | – |

| Total | 18 | 19 | 44 | 6 | 2 |

AA: administrative reasons group; AC: anticoagulated group; AG: antiaggregated group; CHF: congestive heart failure; AKF: acute kidney failure; UTI: urinary tract infection; MM: group with medical imbalances on admission; CT: pre-operative cardiac tests; DVT: deep vein thrombosis.

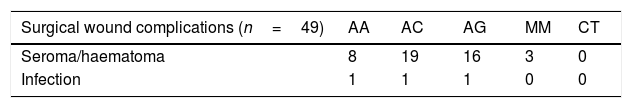

Description of the surgical wound complications.

| Surgical wound complications (n=49) | AA | AC | AG | MM | CT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seroma/haematoma | 8 | 19 | 16 | 3 | 0 |

| Infection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

AA: administrative reasons group; AC: anticoagulated group; AG: antiaggregated group; MM: group with medical imbalances on admission; CT: pre-operative cardiac tests.

Regarding morbidity, in the statistical analysis we observed a higher proportion of complications of the surgical wound in AC patients (40.8%) (p=.063). Higher proportions of general complications in patients of groups AG, AC, MM and CT were observed, with 38.3%, 27.1%, 32.5% and 40%, respectively (p=.3). With regard to overall mortality in our series, 7.51% of patients died one year after surgery (n=20). The proportion of death was higher in the MM group (p=.005), the group with the highest proportion of intracapsular fractures (41.2%), although this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Distribution of complications by groups depending on the reason for delay is contained in Tables 3 and 4. A total of 49 surgical wound complications were noted, 46 of which were seromas or bleeding of the surgical wound and 3 were infections on the wound. On observation of the distribution by groups according to the reason for delay, the majority of the complications focus on the cohort of AC patients, with a total of 19 cases of seroma and one of infection on the surgical wound. With regard to general complication, a total of 89 cases were recorded. Of these, 17 were signs of agitation or delirium, 21 of anaemia, 7 of acute kidney failure, 5 of chronic decompensated heart failure, 14 of abnormal heart rhythm events, 11 digestive problems, 5 pneumonia, 3 urinary tract infection, 2 bed sores and 2 deep vein thrombosis.

DiscussionPailleret et al., in their series between 2011 and 2016 of 39 patients treated with antiaggregation medication (clopidogrel), found no differences regarding the need for transfusion and postoperative complications, only an increase in hospital stay in the group operated on after 48h.10,11

In our series of delay patients (48h or more) we did not find a greater need for transfusion in antiaggregated or anticoagulated patients. The indication for antiaggregation in elderly patients is usually cardiological or neurological, which may predispose them to general complications in this area.

Authors like Cordero et al., with a total of 697 patients operated on between 2012 and 2014 in their hospital, where taking antiaggregant and/or anticoagulant medication was the main reason for the delay, detected that the delay in surgical treatment was associated statistically significantly with a higher rate of heart complications (2.2%) and a higher rate of infection on the surgical wound (3.9%).12 In our series, cardiac complications recorded in the subgroup of antiaggregated and anticoagulated patients (n=185) was 4.3%, concentrating the highest proportion of general complications in the development of anaemia (7.6%) or agitation (5.9%). We also found that in this subgroup of patients, there were a higher proportion of complications regarding the surgical wound with a total of 20 cases in AC and 17 in AG. However, only in one case in each group was infection associated with the surgical wound, treating the other haematomas or seromas without complications.

The presence of medical comorbidities in people with hip fracture is common, due to the fact that these are pluripathological and polymedicated patients. Belmont et al. published a series of 9286 hip fractures, reviewed in different databases in 2008, and analysed the influence of different risk factors on the mortality and development of general complications.13 On the one hand, the presence of previous heart problems, shock or dialysis were associated with higher mortality and on the other, the presence of dialysis, acute respiratory diseases, heart problem or shock was associated with a higher rate of general implication, with a rate of cardiac complications of 2.9% and a mortality rate of 9.1%. In our series, the group of surgically delayed patients due to medical reasons (n=17), i.e. exacerbation of conditions existing prior to hospital admission, recorded a lower rate of cardiac complications (1.2%). However, despite the fact the overall mortality rate recorded in delayed surgery patients one year after surgery was 7.51%, the highest proportion was concentrated in the patient group where surgery was delayed for medical reasons, with a proportion of 29.4% (p=.005). This could have been affected by the lower sample size and the higher mean age in the MM patient group who underwent surgery in our series (81.2 years),with respect to that published by Belmont et al. (72.7 years).

Hospital admission day from Thursday to Saturday is a reason for surgical delay in this and other healthcare systems.14,15 Sánchez-Crespo et al. published a series of 636 delayed hip fracture surgery (with absence of medical comorbidities or anticoagulant or antiaggregant treatment as the reason for surgical delay) and recorded a rate of general complications of 29% and mortality of 18.6%.5 In our series, no statistically significant differences were detected in the subgroup of patients where surgery was delayed for administrative reasons, regarding general complications, at 24.7%, nor did we find any differences with regard to mortality, at 4.1%. These data could have been affected by the presence of a higher proportion of patients with lower anaesthesia risk, with a proportion of ASA 2 of 53.4% in our series, compared with 44.3% in the patient series published by Sánchez-Crespo et al.

We detected limitations to our study which included the fact that the groups were not homogeneous regarding previous ASA and Barthel indexes, with lower scores on the Barthel and ASA scales for the patient group delayed by AA, so that this group of patients without comorbidities, antiaggregation or anticoagulation did not appear to have higher complications if surgery was delayed. We do not know whether this was due to the lower degree of dependence and the ASA classification.

In our series the rate of mortality during the first year after surgery was higher in patients where surgery was delayed for medical comorbidities and delay in treatment due to previous antiaggregation and anticoagulation led to higher general complications and surgical wound complications, after surgery. We would therefore recommend that surgery is performed on all hip fractures, patient status permitting, during the first 48h.

ConclusionThe mortality rate was statistically significantly higher in the group with medical morbidities. When comparing the results of cohorts of antiaggregated, anticoagulated patients and those with medical morbidities, higher rates of general complications were recorded. Higher surgical wound complications were recorded in anticoagulated patients. From our series we can extract the recommendation to perform hip fracture surgery on all hip fracture patients, patient status permitting, during the first 48h, to avoid the presentation of possible complications.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Correoso Castellanos S, Lajara Marco F, Díez Galán MM, Blay Dominguez E, Bernáldez Silvetti PF, Palazón Banegas MA, et al. Análisis de las causas de demora quirúrgica y su influencia en la morbimortalidad de los pacientes con fractura de cadera. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:246–251.