Actinotignum (Actinobaculum) schaalii are considered commensal bacteria of the genital and urinary tract.1 They have been transferred to a new genus, Actinotignum, along with A. urinale and A. sanguinis.2

They are frequently overlooked because of their slow growth and their difficult identification by conventional methods, and their prevalence is very likely underestimated. Newer identification methods, such as MALDI-TOF MS, have made it an emerging pathogen involved in UTIs, but also in other locations such as osteomyelitis, bacteremia and skin infections.3 We describe three unusual clinical presentations of A. schaalii infections.

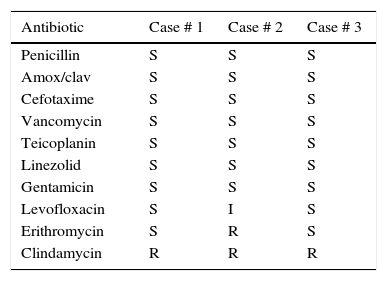

Case # 170-Years-old immunocompetent male, attending to the Emergency Room (ER) because of 48h febricula with shaking chills, malaise and scrotal and perineal pain. Two years before, he suffered a perianal abscess, which evolved to a Fournier's gangrene with several sepsis episodes. The exploration showed a scrotal abscess which was drained. After 48h incubation, grayish colonies growing on blood agar plates were identified as A. schaalii by MALDI-TOF MS (MicroFlex, Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany). Antibiotic susceptibility was tested by the disk diffusion method (Table 1). The patient received amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 2 weeks, remaining asymptomatic thereafter.

Case # 243-Years-old male attending to the ER because of 1-month dysuria. Empirical treatment with ciprofloxacin led to an initial improvement with relapse within a few days. Azithromycin was then started, with no improvement. When the patient returned to the ER, he was afebrile, but he referred a purulent urethral discharge, hemospermia, hematuria and painful erection. Blood count and serum biochemistry were normal. Hematuria and pyuria, but not bacteriuria, were observed. Empirical treatment with cefixime was started, but one month later the patient had not improved. He continued with leucocyturia, so urine and urethral discharge samples were sent for culture, and empirical treatment with ciprofloxacin was started. The patient improved, and cultures were negative. Four months later the patient got back to the Urology office with hematuria and urethral discharge, but no specific pain. Prostate ultrasounds study showed prostatic parenchyma calcifications, suggesting chronic prostatitis. Urethral discharge culture was again performed, and this time A. schaalii was isolated and identified (MicroFlex, Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany). Disk diffusion susceptibility appears in Table 1. After two weeks with amoxicillin-clavulanate, urethral discharge disappeared, control urine cultures were negative, and the patient was asymptomatic.

Case # 370-Year-old woman, who attended to her primary care doctor because she had detected a 2cm lump in her right breast areolar area. No skin or nipple retraction, galactorrhea, or axillary lymphadenopathies were observed. Mammography and breast ultrasound study detected an echogenic nodule in the right breast internal retroareolar area, with no invasion signs. A fine needle aspiration was performed. Gram positive rods were observed, and grayish colonies grew on blood agar, which were identified by MALDI-TOF MS (MicroFlex, Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany) as A. schaalii. Disk diffusion susceptibility appears in Table 1. The patient was treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for ten days. One month later the nodule had disappeared and the patient was asymptomatic.

Though A. schaalii is mainly a urinary tract pathogen4, it is being isolated from other locations with growing frequency. In a study on A. schaalii clinical isolates obtained between 1999 and 2009 in one hospital in Basel (Switzerland), only 30% were obtained from urine, most isolates being obtained from deep tissue infections and bacteremia. As other studies report,5 most of our patients were >60 years old. A. schaalii infections have been associated to urologic-related predisposing conditions,3 as with our patient # 2. Fournier gangrene and skin breast abscess by A. schaalii have also been described.6,7 Very likely, A. schaalii has been underdiagnosed for years. A. schaalii is present, at high bacterial counts, in 33% of urine samples from children with unspecific fever or UTI symptoms.8 Non-UTI infections by A. schaalii have been seldom reported in Spain.9,10 MALDI-TOF MS allow a reliable identification of this microorganism,6 as with our isolates.

To date, specific recommendations to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing do not exist for Actinotignum spp. As a consequence of this lack of specific rules, authors have used both the E-test method and disk diffusion methods.3 Here we have used the disk diffusion method on 5% blood Mueller Hinton agar, and the CLSI guidelines for streptococci. A. schaalii has been reported usually susceptible to β-lactams, excepting mecillinam, gentamicin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, tetracyclines, rifampicin, nitrofurantoin and linezolid. Is frequently resistant to macrolides (50%), clindamycin (25%) and ciprofloxacin, but usually remains susceptible to levofloxacin.3 The susceptibility of our three isolates correlates with this profile, though all our isolates were clindamycin-resistant.

In conclusion, A. schaalii is an emerging uropathogen that is being increasingly detected as responsible for invasive infections. Microbiology laboratories shall include appropriate culture protocols for detecting its presence in urine, but also in invasive infections. MALDI-TOF MS will be a valuable resource for its accurate identification.