Viral hepatitis E recruits an increasing interest in Europe. Both locally acquired and imported hepatitis E virus (HEV) infections have been found in the region, and responded to specific viral genotypes.1 Most patients displayed a mild, self-limited disease, but chronic infection progressing to liver cirrhosis was found among patients with impaired immunity. HEV persistence is at present a matter of concern in the organ transplant setting.2

The National Centre of Microbiology (NCM) performed testing for antibody to HEV (anti-HEV) from year 2000,3 and developed molecular assays for HEV RNA testing and genotyping a few years later.1 Results obtained from these studies were communicated recently.4 Request for HEV diagnosis from centres of the National Health System (NHS) grew, however, significantly after that communication, as well as the number of positive cases found and the data available from the patients involved. The aim of the present report was to update this information.

Samples sent for study were from patients displaying symptoms or signs of acute hepatitis testing negative for hepatitis A, B and C virus markers of acute infection at origin. All samples were collected in years 2004–2011. Both samples sent for primary diagnosis of acute hepatitis E and for confirmation of results obtained at origin were studied. Anti-HEV IgG and IgM, and HEV RNA, were tested in all samples by methods described elsewhere.1,4 Such methods included testing for anti-HEV IgG and IgM by recombinant immunoblot on all samples. Follow-up samples from some patients were occasionally received and studied. Diagnostic criteria for acute HEV infection were as follows: (1) anti-HEV negative, HEV RNA positive (window period); (2) anti-HEV IgM positive, HEV RNA positive (early seroconversion stage); (3) anti-HEV IgM positive, HEV RNA negative (post-seroconversion stage); and (4) seroconversion to anti-HEV IgG on follow-up.

Any reactivity to anti-HEV IgG in absence of anti-HEV IgM and HEV RNA was interpreted as reflecting an HEV infection in the past, but not in relation to the acute disease studied. The finding of anti-HEV IgG in samples from up to 3.6% of adults from the general population of the Community of Madrid5 supports such interpretation. Presence of specific IgM antibody to human cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was excluded in all samples satisfying the third diagnostic criteria, in order to exclude anti-HEV IgM reactivity unrelated to HEV infection.6 Follow-up samples from patients negative for anti-HEV IgM and HEV RNA were just exceptionally sent for study.

HEV genotype was investigated in samples testing positive for HEV RNA as described elsewhere.1

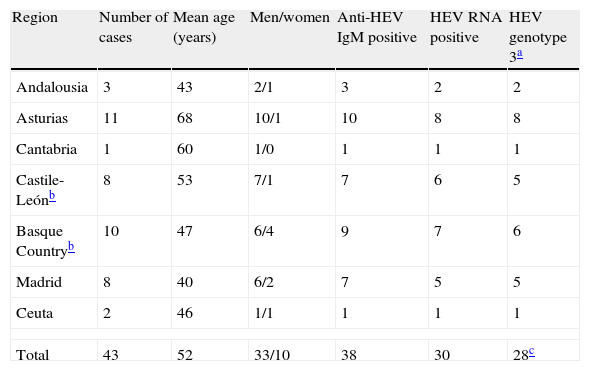

Tables 1 and 2 summarise the main characteristics of the 67 cases of acute hepatitis E collected. Autochthonous cases (43 cases, Table 1) were found mainly among men (77%) aged about 50 years (mean: 52 years; range: 21-86), and most were sent from regions from the Northern half of Spain (70%). Seven of the eight cases from the region of Castile-León were from the province of León, in the North of the region. Together with cases from Asturias, the Basque Country and Cantabria, they accounted for 67% (30/43) of the cases collected. Genotype 3 HEV strains were found in all cases positive for HEV RNA that could be typed (28/30).

Cases of acute hepatitis E diagnosed among patients who did not travel abroad recently before the onset.

| Region | Number of cases | Mean age (years) | Men/women | Anti-HEV IgM positive | HEV RNA positive | HEV genotype 3a |

| Andalousia | 3 | 43 | 2/1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Asturias | 11 | 68 | 10/1 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| Cantabria | 1 | 60 | 1/0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Castile-Leónb | 8 | 53 | 7/1 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| Basque Countryb | 10 | 47 | 6/4 | 9 | 7 | 6 |

| Madrid | 8 | 40 | 6/2 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| Ceuta | 2 | 46 | 1/1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 43 | 52 | 33/10 | 38 | 30 | 28c |

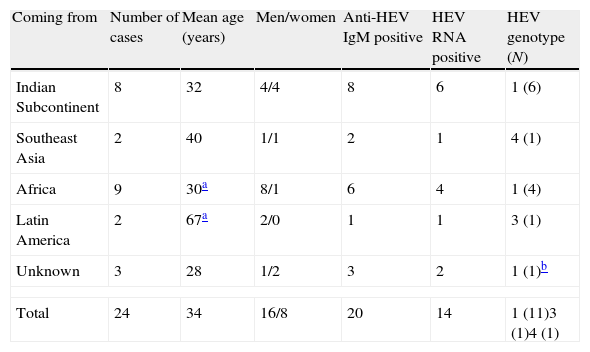

Cases of acute hepatitis E diagnosed among travellers and immigrants coming into Spain after or shortly before the onset.

| Coming from | Number of cases | Mean age (years) | Men/women | Anti-HEV IgM positive | HEV RNA positive | HEV genotype (N) |

| Indian Subcontinent | 8 | 32 | 4/4 | 8 | 6 | 1 (6) |

| Southeast Asia | 2 | 40 | 1/1 | 2 | 1 | 4 (1) |

| Africa | 9 | 30a | 8/1 | 6 | 4 | 1 (4) |

| Latin America | 2 | 67a | 2/0 | 1 | 1 | 3 (1) |

| Unknown | 3 | 28 | 1/2 | 3 | 2 | 1 (1)b |

| Total | 24 | 34 | 16/8 | 20 | 14 | 1 (11)3 (1)4 (1) |

Imported cases (24 cases, Table 2) were found mainly among young men (mean age: 30–37 years; 67% men) coming not only from the South of Asia (10/24, 42%), but also from Africa. With the single exception of one HEV strain from genotype 4 imported from Vietnam by a Spanish tourist, viral strains involved in infections imported from these continents were from genotype 1 (11 strains). Genotype 3 HEV RNA was detected in one of two travellers coming back from Latin America.

According to the criteria described above, most samples (37/67, 55%) were taken at the early seroconversion stage of the acute HEV infection. Sampling at the post-seroconversion stage was less frequent (22/67, 33%). Noteworthy, sampling at the window period was found in six cases (9%). Samples from two patients tested negative for anti-HEV IgM and HEV RNA, but seroconversion to anti-HEV IgG on follow-up provided a basis for the diagnosis. Just one case testing positive for anti-HEV IgM and negative for HEV RNA was excluded from the collection because of presence of IgM antibody to EBV (data not shown).

HEV testing accounts among the services offered by the NCM to the Spanish National Health System, and samples are studied on demand. The meaning of the data obtained from these studies is, therefore, subjected to several limitations, but they are valuable until prospective studies are undertaken in Spain, and may be of help for the design of these studies. Nevertheless, the collection of acute HEV infections from the present report was obtained from the study of samples sent by 60 hospitals emplaced in 14 of the 17 Autonomous Communities of the Spanish State, with no major bias in regard to any particular geographical area of the country (data not shown).

A particular geographical area of the North of Spain, accounting for about 8.5% of the population of the country, harboured 67% of cases of locally acquired, acute hepatitis E collated. The regions involved share many aspects in common in regard to natural environment and to human agricultural activity. Raising of bovine livestock is an important activity, and swine livestock is much less frequent than in other regions of Spain. Anti-HEV has been found in 11% of serum samples from cattle in Catalonia,7 and HEV genotype 4 has been found in stool from bovine livestock from the Chinese region of Xinjiang.8

Most cases of imported disease were found among travellers and immigrants coming from Asia or Africa. Besides Latin Americans account for the highest percent of the immigrants coming to Spain every year, just two cases of acute hepatitis E likely acquired in this region were found. Both corresponded to Spanish travellers coming back from Mexico and the Dominican Republic, respectively. Genotype 3 HEV RNA was found in the second one. Circulation of HEV in the Caribbean has been reported from Cuba, and just genotype 1 strains were identified.9 The real origin of this infection remains, therefore, uncertain.

A significant proportion (9%) of cases of the present collation were sampled at the window period. Centres selecting cases for study after anti-HEV IgM testing could not detect infections at that early stage, and additional cases of acute hepatitis E would have been missed by them if follow-up samples from patients testing negative for specific IgM antibody were not studied routinely. No explanation for the negative results for anti-HEV IgM and HEV RNA could be found for two cases diagnosed just by seroconversion to anti-HEV IgG on follow-up.

In conclusion, this update confirms, on a significantly wider basis, the data reported before in regard to hepatitis E in Spain.4 Locally acquired HEV infections might be significantly more frequent in particular regions of the North of Spain, are always due to HEV genotype 3 strains, and would mainly involve men aged about 50 years. These findings do not fit what should be expected if HEV transmission was mainly related to close contact with swine livestock, or to consumption of raw pork meat. The involvement of bovine livestock as a reservoir for transmission of HEV infection to humans3 would, therefore, be supported by the new data as a reasonable research hypothesis. Active surveillance of acute hepatitis E as an imported disease introducing regularly exotic, potentially epidemic HEV genotypes into Spain seems, in addition, necessary, and should be considered by the public health authority.

The authors thank the colleagues from centres of the SNHS who sent samples and information from cases included in the present report. Marta Fogeda enjoyed a contract supported by grant 1429/05-17 from the Direction General of Public Health, Ministry of Health and Social Policy, during some of the period of time of the study.