The healthcare worker involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event can become second victim. These workers suffer physically and psycho-socially and try to overcome the post-event emotional stress by obtaining emotional support in a variety of ways. The goal of this research was to study second victims among health care providers in Italy.

MethodsThis contribution contains the results of 33 interviews of nurses, physicians and other healthcare workers. After institutional approval, the semi-structured interview, composed of 25 questions, was translated from English into Italian. The audio-interviews were transcribed on paper verbatim by the interviewer. It was then verified if the interviewees experienced the six post-event stages of second victim recovery previously described within the literature.

ResultsThe interviewees described the post-event recovery stages described by literature but stages were not detailed in the exact succession order as the American study. All participants clearly remembered the adverse event and referred the physical and psycho-social symptoms. The psychological support obtained by second victims was described as poor and inefficient.

DiscussionThe post-event recovery pathway is predictable but not always clearly respected as defined within this Italian sample. Future study of the second-victim phenomenon and desired supportive interventions is necessary to understand the experience and interventions to mitigate harm of future clinicians. Every day healthcare workers become second victims and, considering that human resources are the most important heritage of healthcare infrastructures, after an adverse event it is very important to execute valid interventional programs to support and train these workers.

El trabajador sanitario implicado en un episodio adverso imprevisto de un paciente puede convertirse en la segunda víctima. Estos trabajadores sufren física y psicosocialmente, y tratan de superar de varias maneras el estrés emocional posterior al episodio mediante la obtención de apoyo emocional. El objetivo de esta investigación fue estudiar segundas víctimas entre el personal sanitario en Italia.

MétodosEsta contribución contiene los resultados de 33 entrevistas a enfermeras, médicos y otros profesionales sanitarios. Después de la aprobación institucional, la entrevista semiestructurada, compuesta por 25 preguntas, se tradujo del inglés al italiano. El entrevistador transcribió las entrevistas sonoras literalmente. A continuación se comprobó que los entrevistados hubieran experimentado las 6 etapas de recuperación posteriores al episodio de segunda víctima descritas en la bibliografía.

ResultadosLos entrevistados describieron las etapas de recuperación posteriores al episodio descritas en la bibliografía, pero las etapas no se presentaron en el orden de sucesión exacto en que aparecieron en el estudio norteamericano. Todos los participantes recordaban claramente el episodio adverso e hicieron referencia a los síntomas físicos y psicosociales. El apoyo psicológico obtenido por las segundas víctimas se describió como deficiente e ineficaz.

DiscusiónLa vía de recuperación posterior al episodio es previsible, pero no siempre se respeta con claridad, como se define en esta muestra italiana. Es necesario un futuro estudio sobre el fenómeno de la segunda víctima y las intervenciones de apoyo deseadas para entender la experiencia y las intervenciones para atenuar el perjuicio de los futuros médicos. Cada día, trabajadores sanitarios se convierten en segundas víctimas, y teniendo en cuenta que los recursos humanos son el patrimonio más importante de las infraestructuras sanitarias, después de un episodio adverso es muy importante ejecutar programas de intervención válidos para apoyar y formar a estos trabajadores.

Albert Wu used the term “second victim”, for the first time, on 2000.1 A second victim was defined as “a healthcare worker involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, in a medical error and/or a patient related-injury who become victimized in the sense that the worker is traumatized by the event. Frequently, second victims feel personally responsible for the patient outcomes. Many feel as though they have failed their patient and feel doubts about their clinical skills and knowledge base”.2,3 Recent studies show the prevalence of second victims3–6 and point out that most of second victims struggle in isolation, both personally and professionally. This also has a negative impact on their colleagues, supervisors, managers, patients, and organization.7,8

According to literature addressing the needs of health care's second victims need to become part of national and local patient safety and quality improvement initiatives.7 Senior organizational leaders should organize and support the organization support network. Second victims should be encouraged to be actively involved in the design and development of support structures.9

“Second victims” are an emerging problem also in Italy, underlined by the Ministry of Health Care in 2011 that published “Guidelines for manage and communicate Adverse Events in Health Care”. This document specifies the necessity to support the operators involved in an adverse event and assess the impact that this event has on the involved operators and staff in order to adopt appropriate strategies to ensure the event become a learning source and not a demotivational one.10

The goal of this research was to study second victims in Italy.

Specific objectives were:

- 1.

to describe the physical and psycho- social impact of an adverse event on second victim;

- 2.

to specify the recovery course after an adverse event;

- 3.

to describe the actual assistance provided to the second victims.

A research quality–quantity strategy has been used for this study. After approval from institutions (SN5518) to investigate about impact and support concept for second victims, nurses, doctors and other healthcare workers were identified to poll with semi-structured interviews.

The four-person team, consisting of two safety/risk management experts, one registered nurse, and one sociologist, determined an interview schedule. A 25-item semi-structured interview guide was used and included personal and professional demographics, participant recount of adverse event circumstances, physical/psychosocial symptoms experienced and recommendations for improving post-event support.2

The text translation validation followed this path: two scientific translation experts of Italian native language with a base medical education translated the text from English into Italian; both noted the difficulties to translate some words into Italian. Then they made a comparison of the two versions to draw up a shared translation. Then a scientific translation expert (English–Italian) of English native language translated this version again into English to verify the translation accuracy. Thus, the final guide translation was drawn up with addition of a question about the “symptom term” (question 23) considered relevant for the research (Annex 1).

Ethics statementThe study was exempt from review by the Ethics Committee of Novara as it exclusively used confidential data provided by not qualified as “weak or protect” (Protocol number SN5518).

Study designThe study was realized both on a territorial and on hospital level in the Local Health Authority District of Vercelli and in the University Hospital “Maggiore della Carità” of Novara.

The interviews occurred in a location selected by the participants (i.e. office, house, etc.).

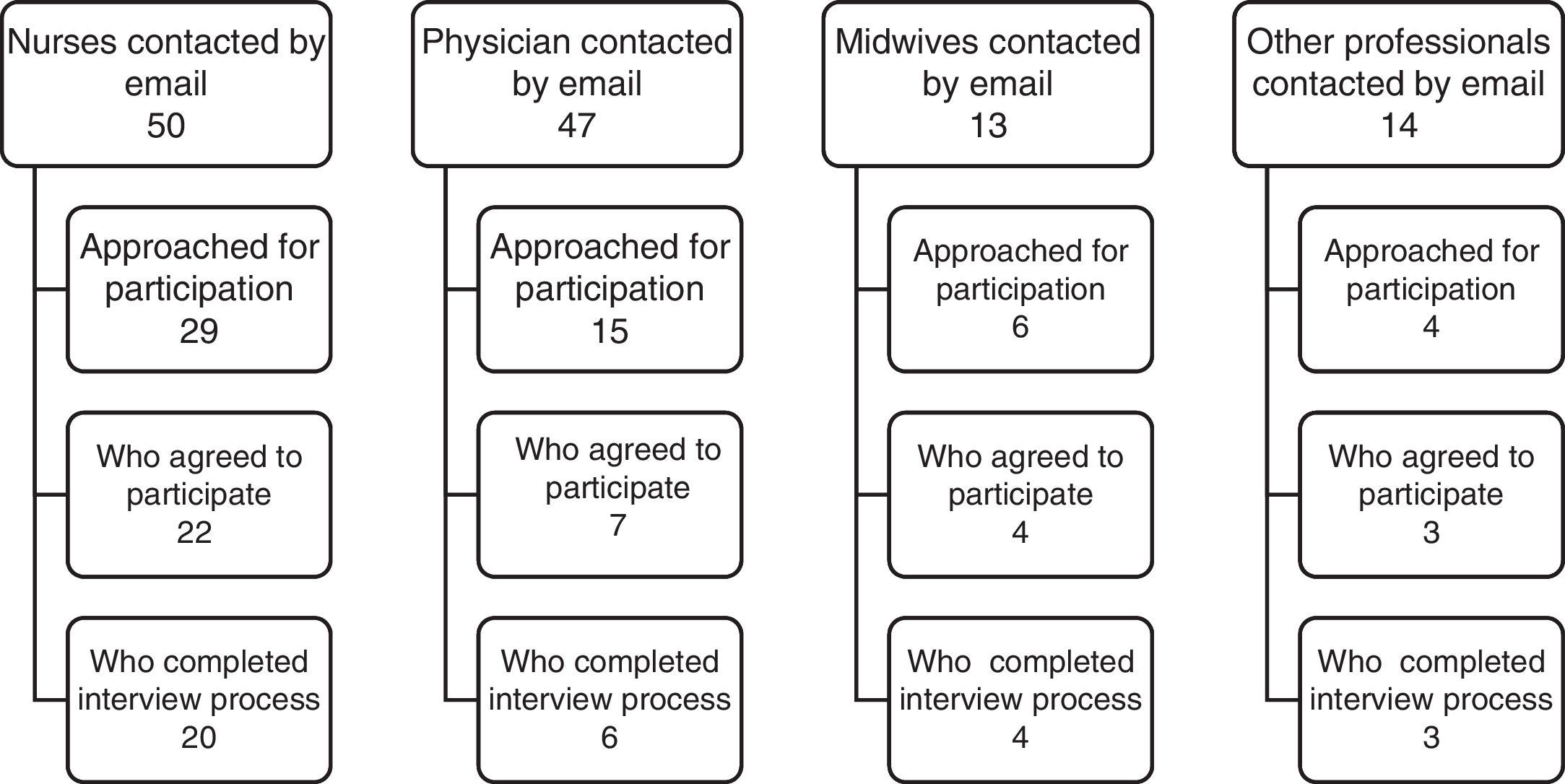

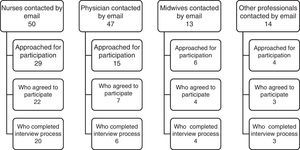

SampleAccording to Scott's study, the goal was to interview at least 30 healthcare workers. For this study, all the health care workers of two organizations were invited to participate and were informed of the project scope by their director and/or coordinator. Those who were interested were contacted by e-mail. Those who accepted to participate received additional information by the research team. All respondents had experienced at least one adverse event describing the most serious adverse event. For details on the participant selection, see Fig. 1.

Interview procedureWritten informed consent for participation in the study was obtained (according to Italian law).

The participants were assured anonymity and confidentiality and they signed the consent form to protect their own privacy in compliance with the law in force. The interview was conducted one-to-one in Italian language. The duration of an interview was about 60min. The interview was audiotaped and field-notes were taken to maintain contextual details and non-verbal expressions.11 Upon conclusion of each interview, recordings were assigned a subject number and identified by professional group. Tapes were transcribed by one person while another one was verifying de-identification and transcription accuracy.2 The interviews were conducted from July 2012 to January 2013.

Data analysisWhile reading the interview texts the recurrent terms and questions of the participants were identified. It was verified if the participant passed through the six post-event phases stated by literature.2 Two persons executed this part of the job separately: the interviewer and a psychologist experienced in healthcare worker support. Then, they compared their results to test their agreement (Cohen's kappa=0.82). Another psychologist was consulted in case of doubt. The data were analyzed according to the Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven (QUAGOL) guideline12 and classified using MAXQDA software.

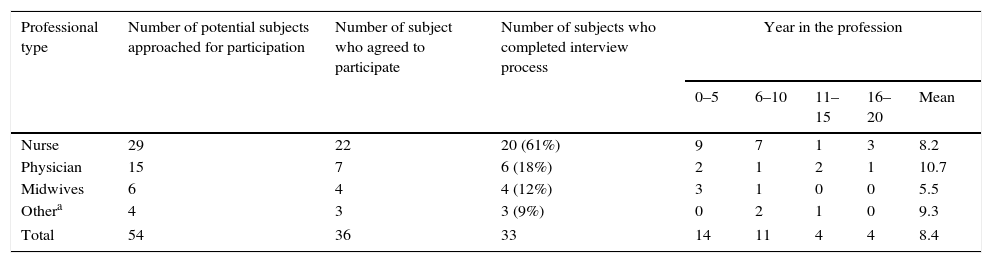

ResultsThirty-three health care professionals completed the interview. The sample was composed of nurses, physicians, midwives and other professionals. Table 1 demonstrates the specific professional group features. Subjects that accepted the enrolment expressed uneasiness and doubts about the possible medical-legal consequences of the occurred event, notwithstanding the warranty of privacy protection. Moreover, three persons did not conclude the enrolment; because they did not desire to revisit the event for the uneasiness of memory. 61% of participants were women (n=20). Years in the profession ranged from 3 to 20 years.

Interview participation by professional group.

| Professional type | Number of potential subjects approached for participation | Number of subject who agreed to participate | Number of subjects who completed interview process | Year in the profession | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | 6–10 | 11–15 | 16–20 | Mean | ||||

| Nurse | 29 | 22 | 20 (61%) | 9 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 8.2 |

| Physician | 15 | 7 | 6 (18%) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10.7 |

| Midwives | 6 | 4 | 4 (12%) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5.5 |

| Othera | 4 | 3 | 3 (9%) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 9.3 |

| Total | 54 | 36 | 33 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 4 | 8.4 |

Time since the adverse event occurred ranged from 5 months to 132 months (mean 56.5 months).

The research questions have been addressed has it follows.

- 1.

What are the physical and psychosocial symptoms of an adverse event on second victim?

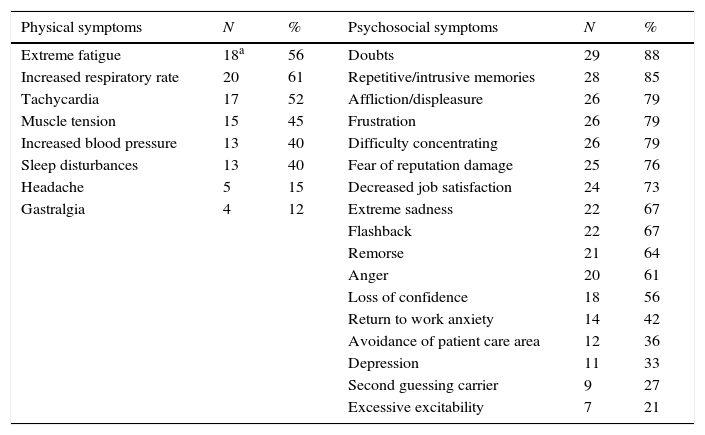

All the participants clearly remembered the unanticipated clinical event (Table 2). In addition to the symptoms most commonly reported in literature13–18 five subjects remembered experiencing a headache after the event and in the days after the event and four subjects referred gastralgia.

Table 2.Most commonly reported physical and psychosocial symptoms.

Physical symptoms N % Psychosocial symptoms N % Extreme fatigue 18a 56 Doubts 29 88 Increased respiratory rate 20 61 Repetitive/intrusive memories 28 85 Tachycardia 17 52 Affliction/displeasure 26 79 Muscle tension 15 45 Frustration 26 79 Increased blood pressure 13 40 Difficulty concentrating 26 79 Sleep disturbances 13 40 Fear of reputation damage 25 76 Headache 5 15 Decreased job satisfaction 24 73 Gastralgia 4 12 Extreme sadness 22 67 Flashback 22 67 Remorse 21 64 Anger 20 61 Loss of confidence 18 56 Return to work anxiety 14 42 Avoidance of patient care area 12 36 Depression 11 33 Second guessing carrier 9 27 Excessive excitability 7 21 Repetitive/intrusive memories are the most commonly referred psychosocial symptoms, thus respectively 88% and 85% of participants expressed the following thought: “I thought about the event and I continuously thought to have made the wrong choice. What could I have done differently? I had doubts even about things that I repeated every day” and “The day after I was resting at home, preparing dinner and remembering the incident phases. I did not want to remember that moment, but the memories came anyway and I almost detached a finger while cooking!”.

42% of interviewees referred of anxiety in returning to work: “I was so anxious, I was thinking about when I’d returned to work and I was really bad”.

27% thought to the possibility to change work: “After the event I kept thinking and thinking, I couldn’t give myself peace, I thought of going mad and at a point I seriously thought I could not do that job yet”.

Many interviewees referred to revisit the event still today, especially when they engage with a patient with a care pathway similar to the one of adverse event: “When I have to treat a patient who has the same disease, in the same bed or with the same complications, I start to think back to that day and I feel fear”.

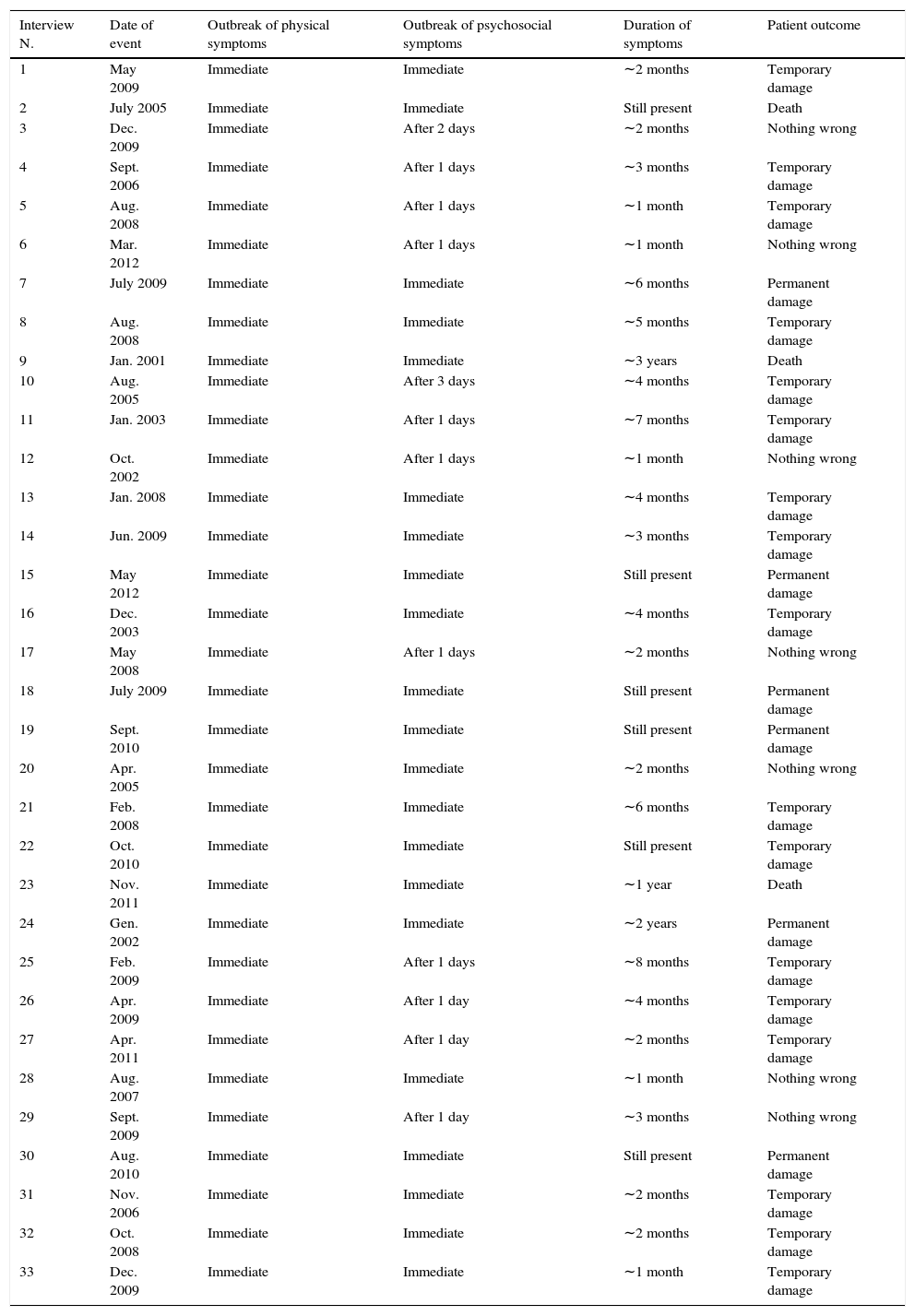

The reported physical symptoms appeared immediately after the event, while the psychosocial ones19,20 occurred during different time intervals. Even the duration was variable and seemed to be related to the event response of the patient,21–23 after serious damage there is longer duration of symptoms. 18% of the interviewees referred to continued suffering from some symptoms related to the event (Table 3).

Table 3.Elapsed time between the event and the outbreak of the first symptoms.

Interview N. Date of event Outbreak of physical symptoms Outbreak of psychosocial symptoms Duration of symptoms Patient outcome 1 May 2009 Immediate Immediate ∼2 months Temporary damage 2 July 2005 Immediate Immediate Still present Death 3 Dec. 2009 Immediate After 2 days ∼2 months Nothing wrong 4 Sept. 2006 Immediate After 1 days ∼3 months Temporary damage 5 Aug. 2008 Immediate After 1 days ∼1 month Temporary damage 6 Mar. 2012 Immediate After 1 days ∼1 month Nothing wrong 7 July 2009 Immediate Immediate ∼6 months Permanent damage 8 Aug. 2008 Immediate Immediate ∼5 months Temporary damage 9 Jan. 2001 Immediate Immediate ∼3 years Death 10 Aug. 2005 Immediate After 3 days ∼4 months Temporary damage 11 Jan. 2003 Immediate After 1 days ∼7 months Temporary damage 12 Oct. 2002 Immediate After 1 days ∼1 month Nothing wrong 13 Jan. 2008 Immediate Immediate ∼4 months Temporary damage 14 Jun. 2009 Immediate Immediate ∼3 months Temporary damage 15 May 2012 Immediate Immediate Still present Permanent damage 16 Dec. 2003 Immediate Immediate ∼4 months Temporary damage 17 May 2008 Immediate After 1 days ∼2 months Nothing wrong 18 July 2009 Immediate Immediate Still present Permanent damage 19 Sept. 2010 Immediate Immediate Still present Permanent damage 20 Apr. 2005 Immediate Immediate ∼2 months Nothing wrong 21 Feb. 2008 Immediate Immediate ∼6 months Temporary damage 22 Oct. 2010 Immediate Immediate Still present Temporary damage 23 Nov. 2011 Immediate Immediate ∼1 year Death 24 Gen. 2002 Immediate Immediate ∼2 years Permanent damage 25 Feb. 2009 Immediate After 1 days ∼8 months Temporary damage 26 Apr. 2009 Immediate After 1 day ∼4 months Temporary damage 27 Apr. 2011 Immediate After 1 day ∼2 months Temporary damage 28 Aug. 2007 Immediate Immediate ∼1 month Nothing wrong 29 Sept. 2009 Immediate After 1 day ∼3 months Nothing wrong 30 Aug. 2010 Immediate Immediate Still present Permanent damage 31 Nov. 2006 Immediate Immediate ∼2 months Temporary damage 32 Oct. 2008 Immediate Immediate ∼2 months Temporary damage 33 Dec. 2009 Immediate Immediate ∼1 month Temporary damage - 2.

What is the recovery course after an adverse event?

This study confirmed that the clinician second victims passed through six distinct post-event recovery stages. However, sequencing of some of the stages varied for some of the clinicians. The interviewees referred to continued suffering from some symptoms related to the event. All participants experienced with different timings, but in the same order, the first two stages. The next four stages were lived by all participants but not in the same order. According to literature, stage-1 was characterized by a rapid awareness and identification of the unanticipated clinical event: all research participants identified their clinical error and requested clinical assistance to stabilize their patients. Sometimes the healthcare provider is not able to continue to provide support to patient and is confused. In this stage the most frequent questions were: what did that happen? Why did that happen?

This was the first stage for all participants. An example of this phase: “I immediately realized the mistake, I asked for help to my colleague near me to intervene on the patient, I was having trouble concentrating and I was afraid to wrong, I was not able to do what I did so many times. I did not understand how it happened. I was in so much shock”.

Stage-2 presented intrusive reflections, periods of self-isolation, feeling of internal inadequacy and repeatedly re-evaluation of the event. The second victim continued to think what would have happened if they would have done it differently. The frequently asked questions were: could this have been prevented? What did I miss? An example of this stage: “…I was tormented; I thought maybe if I’d have done it this way, I lost my confidence for some time. I’d stay alone in thinking to what happened. More and more I thought I was bad. It was terrible”.

Stage-3 was described as seeking support from persons, generally colleagues or supervisors, as they are afraid to lose their confidence. In this stage, the “hospital's gossip” and the department's teamwork culture are important for the situation to progress. The second victim was afraid to lose trust of colleagues; this occurred when the event was followed by non-supportive departmental support. 30 participants lived this stage as third while three lived it as fourth.

The most frequently asked questions were: What will others think? Will I ever be trusted again? How can I face the problem? Could the patient and their relative understand? How come I cannot concentrate?

30 participants lived this phase as third while three lived it as fourth.

An example of this stage: “I was sorry for the patient but egoistically I thought to what the colleague said, they gossip me every day. I could not go on, I asked for another week of holiday and I hadn’t the courage to return to work, they thought I was an idiot and they were never going to trust me again… it was really depressing” and “…I thought and thought, I was having trouble concentrating in my private life, I was absent and I felt more stupid for this. I thought I was going mad, I went out for not staying at home and I asked myself how could I go on and I was not sure to overcome it”.

In the stage-4, the second victim started to wonder about repercussions affecting job security, licensure and future litigation. Second victim tended to seek emotional support in colleagues and supervisors, asked themselves what and how to tell the event to their and patient relatives. The second victims thought about the severity event level. 30 participants lived this stage as fourth while three lived it as third.

The most frequently asked questions were: what happens next? Is this the profession I should be in? Where can I turn for help? Why did I response in this manner?

An example of this stage: “I worked there for one year and I had an open-end contract; I was afraid to talk to my supervisor, surely I should receive a written warning, but I thought to the contract extension and then … what could I tell? I was new, in a shark place even who were older than me would act in the same way … but prove it was something else” and “I told the event to my colleagues, but I could not tell everyone what happened. Also at home, I would like to tell to my partner but I would not tell exactly what happened… it never knows. In addition to the troubles that I should have, I could be punished for privacy violation …. Nowadays you need to be really careful” and “I wanted to talk to little G parents, but sincerely I didn’t know how to face them, how to explain I thought I did my best for their child and that the response was unexpected. They would not believe me… in fact they already reported the event and I started to think if I filled out the clinical documents in a right way”.

In stage-5 the second victims tended to seek emotional support, but they did not know how and to whom to ask for help, they did not know if there was the possibility to contact an expert; however, the support supplied was ineffective. 28 participants (85%) declared to be unsatisfied with the support supplied. This was the fifth stage for all participants.

The more frequent questions of this stage were: Where can I turn for help? What I really need? What is wrong with me or is it normal to I react in this way? How could I have prevented this from happening?

An example of this stage: “I talk to my shaft-colleagues and then also with other two to whom I felt bound, but they told me to not worry, they belittled what happened, but I knew that the all thing was not trivial, I wished that someone say that I was wrong and that it was human to make mistake and that I should talk to a psychologist. I felt disappointed and denigrated. The physician gave me a pat on the back and then I felt more stupid. A pat on the back, what did it mean? Did they feel sorry for me or everything I made was right? What did that mean? I wonder it even now…” and “The first days, they seemed worried for me, they also called me at home, then… nothing, even when I returned to work, nobody asked, it seemed they forgot it, but I knew that it was not so and particularly I did not forget” and “I wanted to talk to someone that could really help me, but I did not know with who. Everybody said it was better to silence everything and it would be better to go to a private psychologist and not where I was working” and “I wished there had been someone explaining me why I felt so bad, I tried to give myself explanations, but I was unsatisfied and I restarted to visit the event and to ask myself how should I have done”.

In stage-6 Scott described three possible ‘career outcome’ paths experienced by the clinician secondary to the unanticipated clinical event:

- -

1st-path: consider leaving position, changing job or workplace;

- -

2nd-path: survive, going on and coping without forgetting;

- -

3rd-path: thrive by closely reviewing event details and actively participating in enhancing care delivery for future patients.

None of the second victim research participants changed or left their clinical role or position (1st path). The most frequently asked questions that second victim made in the 2nd-path of surviving were: Why do I still feel so badly? Can I still overcome the event or will I be affected forever? Could I have prevented it? The most frequently asked question of the 3rd-path were: What can I do to improve patient safety? What can I learn from this? What can I do to make care better? The majority of participants (90%) declared not to have overcome the event, even after many years. Moreover, following the event, they changed their professional attitude, they were more scrupulous and sometimes they realized to be too thoughtful to perform procedures, taking longer time than normal to realize diagnostic but probably un-useful procedures because they were afraid to make a mistake.

An example of this stage: “After so many years I could not forget, the memory reappears in similar situations especially if a patient has the same disease. I am much sure of myself now that I understand that everybody can make mistakes as me, but I think I had really not forgiven yet” and “I always remember what happened, I don’t feel so bad now, but surely it affected me for life; my way to work has changed from that day: I am more careful, probably too much” and “I changed my way to work, sometimes I require examinations that were not necessary only for the fear of performing wrong diagnosis.”

The remaining 10% declared that had learned from their mistake, had surpassed the feeling of guilt from the event and had become stronger clinicians as a result of the event. An example of this stage: “I risked going mad, I thought and thought; then I talked to a psychologist that really helped me, I understood that my suffering could help somebody else to not repeat my mistake … after 3 months, I obtained that in the department there was a double-check procedure for the chest drain removal…”.

- -

- 3.

What is the actual assistance provided to the second victims?

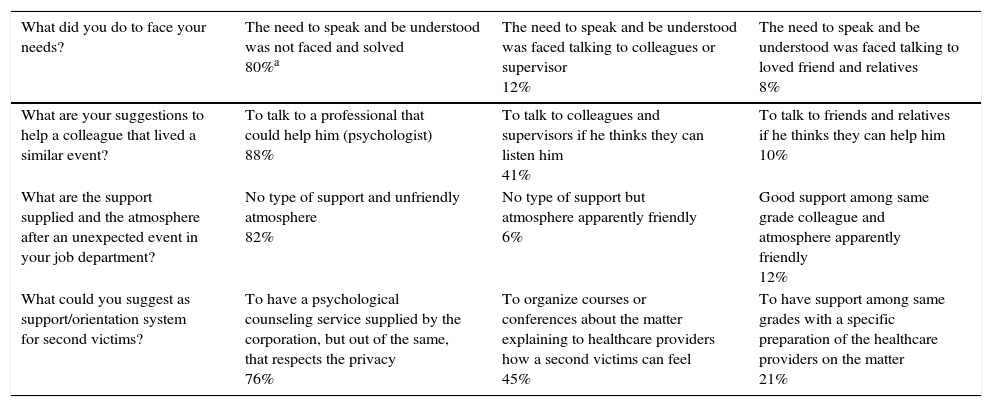

The interviews revealed that none of the second victims received proper emotional support from the respective health care organization. 21 participants (65%) declared that they would have liked to receive support, but they did not know where to ask for it nor if it was possible as an option. 13 participants (40%) sought assistance from a psychologist. Table 4 demonstrates second victim desired versus actual support received.

Table 4.Support for second victims.

What did you do to face your needs? The need to speak and be understood was not faced and solved

80%aThe need to speak and be understood was faced talking to colleagues or supervisor

12%The need to speak and be understood was faced talking to loved friend and relatives

8%What are your suggestions to help a colleague that lived a similar event? To talk to a professional that could help him (psychologist)

88%To talk to colleagues and supervisors if he thinks they can listen him

41%To talk to friends and relatives if he thinks they can help him

10%What are the support supplied and the atmosphere after an unexpected event in your job department? No type of support and unfriendly atmosphere

82%No type of support but atmosphere apparently friendly

6%Good support among same grade colleague and atmosphere apparently friendly

12%What could you suggest as support/orientation system for second victims? To have a psychological counseling service supplied by the corporation, but out of the same, that respects the privacy

76%To organize courses or conferences about the matter explaining to healthcare providers how a second victims can feel

45%To have support among same grades with a specific preparation of the healthcare providers on the matter

21%Some examples: “I would like to talk to a psychologist but I was ashamed, I never listened anybody of my local health corporation that talk to a psychologist for such event” and “When I realized that I really needed help, after about a month, I asked for help to a good psychologist, she helped me a lot, I thought I had serious problems without her help, but it was really expensive”.

This study found similar results as Scott,2 but some important differences emerged from this Italian sample of second victims. In particular, new physical and psychosocial symptoms were identified from this cohort. The differences to point out are that Scott analyzed hospital-based health care providers. In this and in other studies18,24 healthcare providers worked on territory and within different structures. Different drop out emerged: the 67% of the people wanted to participate to the study and 61% has finished the interview while, as regards Scott's study, the participation was 88% and 72% of people finished the interview. These latest data could be related to the subjectivity, to the different culture, or to the management present in the Italian healthcare field. Finally, our study showed that the six post-event recovery stages, described as consequential,2 had been lived by all participants but not within the same sequencing.

The results of the study showed how none of the participants received a proper support from his/her own structure, however other studies report that second victims received support from their own department/unit,24 anyway the support provided seems to be inadequate,8,25,26 in addition the health professionals who participated in another study perceived significant barriers to pursuing counseling after errors.27 As regards the more common questions posed by participant in each one of the 6 post-event stages, we can note that the interviewees reported new frequent questions, and in particular, in stage-3 “Could the patient and the relative understand?”; stage-5 “What I really need”; in stage-6 “Can I still overcome the event or I will be affected forever?” “How could I have prevented this from happening?”. The results of the study showed how none of the participants received a proper support from his/her own structure.

Limits of the studyThis study has some identified limitations. In addition to the common limitations described for qualitative studies12 our findings could be affected by the sample size. The size of “at least 30” does not ensure concept saturation. Furthermore, the selection bias risk has to be considered: actually participants who responded to the email might be deeply affected by this bias and want to share the experience or are stable enough to stand an interview. The feeling of losing the uniqueness of each of the individual interviews is another problem in the analysis of qualitative data.28

Therefore, our results could not be exhaustive. However, they can be of help in better understanding a phenomenon that is under-estimated in Italy and in health care services worldwide. The authors believe that future research is necessary to investigate second victim experiences in a variety of clinical environments because of the possible negative impact on individual clinicians, health care costs and organizations of care.25,26 To ensure safe of care and safety for health professionals, managers, nurse managers, nurses, clinicians and the academic world need to launch and evaluate supportive strategies for second victims. Also, it would be very important to implement the nursing research on second victims phenomenon, in order to strengthen nursing leadership. In conclusion we also concur with previous second victim studies that provision of comprehensive second victim-emotional support is a moral obligation for every health care system.

Trial registrationThe article does not report the results of a controlled health-care intervention

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statementThe study was exempt from review by the Ethics Committee of Novara as it exclusively used confidential data provided by not qualified as “weak or protect” (Protocol number SN5518).

Authors’ contributionsCR participated in the design of the study, performed interviews, performed the semiotic analysis and drafted the manuscript.

FL participated in the design of the study and helped to draft the manuscript.

KV participated in study design.

CD performed some interviews and overhauled the semiotics analysis.

MP conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript.

Conflict of interestNone declared.

We thank Dr. Luigi Azzarone for technical help and writing assistance. We thank Dr. Susan D. Scott for the linguistic revision of the manuscript.