Organisational learning has become increasingly important for strategic renewal. Ambidextrous organisations are especially successful in the current environment, where firms are required to be efficient and adapt to change. Using a structural approach, this study discusses arguments about the nature of ambidexterity and identifies the kinds of human capital that better support specific learning types and HRM practices suited to these components of human capital. Results highlight learning differences between marketing and production units, as well as different HRM practices and human capital orientations. This study points out that human capital mediates between HRM practices and learning.

Organisational learning has become increasingly important as a mechanism for strategic renewal (Kang and Snell, 2009). Currently, growing competitiveness and rapid changes require firms to learn new guidelines in order to compete.

Most research on organisational learning focuses on two alternative approaches: exploration and exploitation. Exploration involves learning outside a firm's current knowledge domains, whereas exploitation involves refining and extending a firm's existing knowledge stocks (March, 1991). Exploration and exploitation tap into different administrative routines and managerial behaviours (Lubatkin et al., 2006) and compete for firms’ scarce resources, so that the firm must manage trade-offs between the two, in what is called ambidextrous learning. Since an organisation that engages exclusively in exploration will ordinarily never gain the returns of its knowledge, and an organisation that engages exclusively in exploitation will ordinarily suffer from obsolescence, exploitation and exploration are complementary; the basic problem facing an organisation is to engage in sufficient exploitation to ensure its current viability and, at the same time, devote enough energy to exploration to ensure its future viability (Levinthal and March, 2003; Prieto et al., 2009). Ambidexterity is the organisation's ability to address two organisational incompatible objectives equally well (Birkinshaw and Gupta, 2013): ambidextrous organisations are aligned and efficient in their management of today's business demands while simultaneously adapting to changes in the environment (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996).

Organisational ambidexterity is a paradigm which need more studies to clarify its meaning and focus (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013; Birkinshaw and Gupta, 2013; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). One of the main concerns is how organisations engage in both exploration and exploitation, and how this may be crucial for the organisational ambidexterity–performance relationship (Junni et al., 2013; Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008; He and Wong, 2004; Katila and Ahuja, 2002). There are different approaches to consider ambidexterity. Structural ambidexterity proposes to create separate structures for different types of activities, because the two sets of activities, routines and mindsets are so dramatically different (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996). Contextual ambidexterity suggests individual employees can make choices between alignment-oriented and adaptation-oriented activities in the context of their day-to-day work (Kang and Snell, 2009; Birkinshaw and Gibson, 2004). Finally, a third approach consists on a sequential ambidexterity, where organisations shift temporally between periods of exploitation and exploration (Burgelman, 2002).

Although this paper explores ambidexterity from a structural angle, do not discard the presence of both explorative and exploitative learning in all the organisational units. The two approaches of learning are possible in every department, but we propose that its presence and importance will differ attending the characteristics of the organisational units. That is, different organisational areas or units may require mainly a different type of organisational learning depending on their activities. Therefore, this article contributes to the literature by identifying the differences between the two approaches of learning, and their importance considering distinct organisational units.

A second aspect that leads us to adopt the structural perspective is to consider that each organisational unit may require a different human capital composition, with different skills, characteristics and ways of managing. This approach is contrary to Kang and Snell (2009), who understand that all people can change their behaviour towards one or another type of learning. Hence, the purpose of this paper is also to identify the most appropriate HRM practices to manage these differing components of HC. It can be expected that a firm should have at least two different HRM systems and that they may foster different learning types. There is little theoretical and empirical evidence about the relationships between these variables, and our aim is to fill this gap. Previous researchers have considered training and development, performance appraisal and compensation practices (Lepak and Snell, 2002; Schuler and Jackson, 2005), and we take these practices into account because they may strongly influence HC and organisational learning.

Our findings make four contributions to the existing literature. First, we discuss the arguments about the nature of an ambidextrous organisation and compare approaches to learning in two departments in each organisation. Second, we identify the HC characteristics that best support different learning types, connecting specialist and generalist HC with exploration and exploitation respectively; and, third, we set out HRM practices that are consistent with the components of HC. Lastly, we show that HC mediates between HRM practices and organisational learning.

The paper is structured in five sections. Following the introduction, section two introduces the conceptual framework of ambidexterity, and section three explicates the role of HC and HRM in the different approaches to learning. We then describe our research methods and results, and state our conclusions.

Ambidextrous organisationsVarious scholars have argued that successful organisations are ambidextrous: they generate competitive advantages through revolutionary and evolutionary change (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996), or exploratory and exploitative innovation (Benner and Tushman, 2003; Jansen et al., 2009). Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) consider that ambidextrous firms can both compete in mature markets (where cost, efficiency, and incremental innovation are critical) and develop new products and services for emerging markets (where experimentation, speed, and flexibility are critical). They are therefore likely to achieve better performance than firms emphasising one at the expense of the other.

The concept of ambidexterity is also implicit in the more recent conceptualisation of dynamic capabilities put forward by Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), who suggest that these capabilities require a blend of the strategic logics of exploration and exploitation. Jansen and colleagues (2009) consider organisational ambidexterity to be a dynamic capability that goes beyond moving from one configuration of competences to another, but rather addresses multiple, inconsistent demands simultaneously. According to Katila and Ahuja (2002) and Hammady et al. (2013), exploitation of existing capabilities is often needed to explore new capabilities, and exploration of new capabilities also enhances a firm's existing knowledge base.

Focusing solely on exploration can lead to failure if firms never collect the profits of their investments (Levinthal and March, 2003). It can also lead firms to neglect improvement and the adaptation of existing routines (March, 1991). However, focusing completely on exploitation can have negative side-effects too. Organisations that engage solely in exploitation will suffer from obsolescence (Levinthal and March, 2003) and are likely to find themselves trapped in a suboptimal stable balance (March, 1991). These assumptions lead us to establish our first hypothesis:Hypothesis 1 Ambidextrous firms will perform better than non-ambidextrous firms.

Even though different organisational units may require different types of organisational learning and may operate independently. They are organisationally interdependent with regard to the achievement of ambidexterity thus, firms must coordinate exploitation and exploration to achieve simultaneity through a shared vision (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2013, 2007; Jansen et al., 2009), senior management team coordination (Smith and Tushman, 2005; Lubatkin et al., 2006) and systems for knowledge integration (Tiwana and Keil, 2007). Structural separation is necessary because the two sets of activities are so different that they cannot coexist effectively. Exploration and exploitation require adapted organisational structures and distinctive sets of routines and styles of management (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2007; Birkinshaw and Gupta, 2013). Exploitation enables organisations to engage in refinement, implementation, efficiency and production, while exploration implements adaptive mechanisms that require experimentation, variation, search and innovation. Exploitation is defined as the refinement and extension of existing competencies, technologies and paradigms exhibiting returns that are positive, proximate and predictable. In contrast, exploration refers to the tendency of a firm to invest resources to acquire entirely new knowledge, skills and processes, to attain flexibility and novelty in product innovation through increased variation and experimentation (Atuaene-Gima, 2005).

Danneels (2002), Benner and Tushman (2003) and He and Wong (2004) have pointed out that exploratory innovations are designed to meet the needs of emerging customers or markets, often using new distribution channels, whereas exploitative innovations meet the needs of existing customers or markets. Exploitative business units would focus on productivity, improving processes and concentrating on formal coordination mechanisms. Explorative business units would have a more open culture, encouraging creativity and giving freedom to explore new ideas thorough less formal integration mechanisms (Jansen et al., 2006). Therefore, the core business units should focus on alignment and exploitation, while units as R&D or business development should emphasis exploration (Prange and Schlegelmilch, 2009; Birkinshaw and Gibson, 2004). While some units will have the responsibility to develop the products and services the market is demanding, others are given the job of prospecting new markets, developing new technologies and keeping track of emerging industry tends (March, 1991). The production department would be in the first group, while the marketing department would be in the second one. These arguments generate the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 2 The ambidextrous nature of organisations results in spatially dispersed exploratory and exploitative units. Production units are likely to focus on exploitation learning, while marketing units are more likely to focus on exploration learning.

Integration between units has been cited as the main challenge of structural separation. Operating and innovation units have often been described as functioning completely separately from one another, and some authors suggest that coordination between units has thus been limited to a few top managers at the corporate level (Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008). In contrast, Tushman and colleagues (2013) have remarked on the importance of cross-unit interactions. While selected mechanisms like senior team integration or cross-unit interactions have been discussed, the more informal integration mechanisms should not be underestimated (Jansen et al., 2009). This study considers three types of mechanisms: top management as integrators, cross-unit interactions and finally more informal integration contacts.

Human capital, human resource management and organisational learningResearchers have pointed out the links between a firm's focus on organisational learning and its knowledge stocks, in which HC plays a vital role. HC is defined as the knowledge, skills and abilities residing with and utilised by individuals (Lepak and Snell, 2002). Kang and Snell (2009) distinguish between generalist and specialist HC and knowledge; it seems reasonable to posit that each type of HC may be related to organisational learning. Because generalists tend to be less entrenched in a particular perspective and have the potential adaptability to discover, comprehend, combine and apply new knowledge, they are more predisposed towards exploratory learning (Kang and Snell, 2009). In contrast, specialists tend to be more effective at assimilating additional in-depth knowledge to their deeper existing knowledge base, and are likely to focus on exploitation. In general, exploration is related to path breaking, improvisation, autonomy and chaos, and emerging markets and technologies. In contrast, exploitation is associated with path dependence, routinisation, control and bureaucracy, and stable markets and technologies (Brown and Eisenhardt, 1998). These considerations imply that organisational units differ in HC structure depending on the type of learning that they require.Hypothesis 3 Specialist HC should encourage exploitative learning (production units), while generalist HC should encourage explorative learning (marketing units).

The literature review suggests that HC may mediate the relationship between HRM practices and learning (López-Cabrales et al., 2011). If different HRM practices determine diverse dimensions of HC, the characteristics of these dimensions should in turn foster organisational learning:Hypothesis 4 HC will mediate the relationship between HRM practices and organisational learning.

Since HC is a key resource for organisational success, its creation, accumulation and re-creation should be a major concern for the firm. In these processes, HRM plays a key role (Lepak and Snell, 2002; Schuler and Jackson, 2005), providing many valuable tools that are necessary to manage, develop and transform human resources into HC. But which practices are most suited to managing HC? Schuler and Jackson (2005) point to training and development, performance appraisal and compensation. Firms can develop different types of HC depending on the training, the appraisal and the incentive system the organisations design, and theses HRM practices have been named as knowledge-based HRM practices by previous authors (Lopez-Cabrales et al., 2009; Lepak et al., 2006; Lepak and Snell, 2002). For instance, firms may develop generalists through extensive training to focus on future skill requirements while encouraging specialist knowledge through intensive training to improve current job-related skills, including also incentive systems to focus on individuals’ performance (Guthrie, 2001).

Therefore, our aim is to identify how these practices leverage HC. HRM is fundamentally concerned with managing HC; it focuses on conserving and enhancing the firm's basic knowledge assets, which are at risk of obsolescence and loss if not well managed.

Organisational units that focus on developing generalist HC tend to use extensive training to focus on future skills requirements beyond current job requirements and attend to employee potential and openness to learn new skills, while organisational units that develop specialist HC use intensive training to improve current job-related skills (Bae and Lawler, 2000; Lepak and Snell, 2002; Kang and Snell, 2009). Exploitation and specialist HC will look for deeper and more localised knowledge and/or repetitive combinative mechanisms in order to obtain well-defined solutions pertinent to firm's existing knowledge domains. Training and development for future skills will likely be connected to exploration and generalist HC, requiring a relatively broad and generalised search to expand the firm's knowledge domains into unfamiliar or novel areas to establish new combinatory mechanisms (Katila and Ahuja, 2002; Kang and Snell, 2009).

Developmental performance appraisal and skill-based pay systems encourage generalists to learn new knowledge and ideas, tolerating error as a natural by-product of learning beyond their current jobs. Developmental performance appraisal allows employees to make decisions, set their own performance goals, and change the ways they carry out their jobs to deal with exceptional circumstances requiring creativity and initiative (Bae and Lawler, 2000). Skill-based pay motivates employees to acquire additional knowledge and skills and is appropriate in new situations (Tremblay et al., 2003). Thus both developmental performance appraisal and skill-based pay should foster exploration learning.

In contrast, behavioural performance appraisal and job-based pay systems reinforce specialists’ performance and effort in their current jobs, by focusing on prescribed procedures or specified results or both (Lepak and Snell, 2002) and on efficiency (Bae and Lawler, 2000). The quick connection between the actions individuals take and the results they achieve is essential here, ensuring conformance to present standards, eliminating uncertainty, and increasing the predictability of individual behaviours at work (Kang and Snell, 2009). Firms use job-based pay when standards are available against which the performance of individuals can be measured. Both behavioural performance appraisal and job-based pay should enhance exploitation learning.

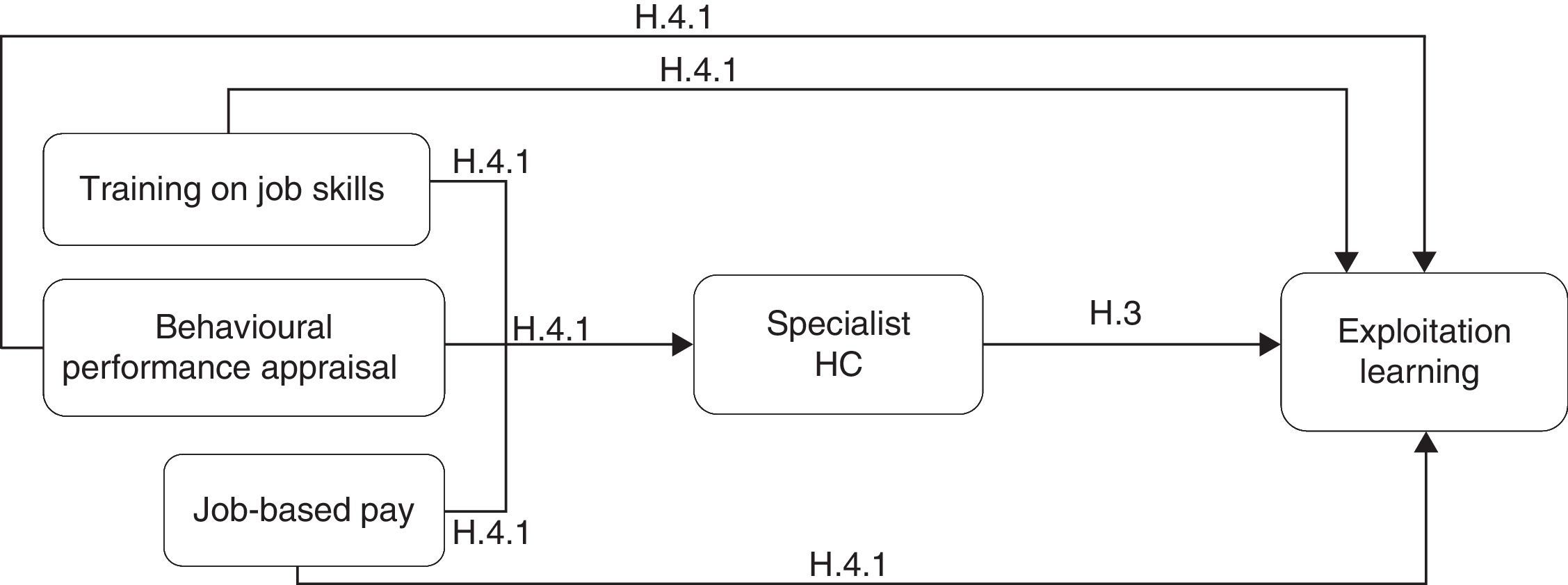

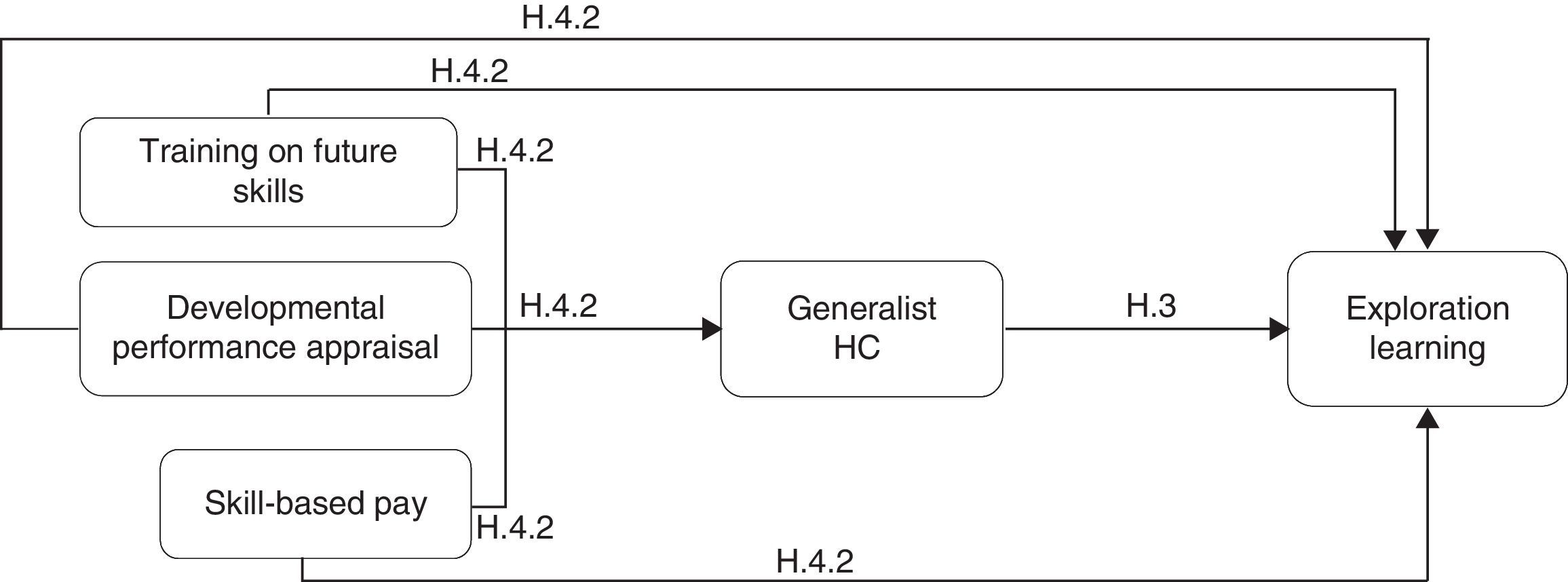

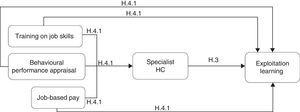

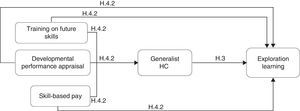

Accordingly,Hypothesis 4.1 Training and development for job-related skills, behavioural performance appraisal and job-based pay should encourage exploitative learning and specialist HC. Training and development for future skills, developmental performance appraisal and skill-based pay should encourage exploratory learning and generalist HC (Figs. 1 and 2). Theoretical model for production department (H2). Theoretical model for marketing department (H2).

Our data come from a sample of manufacturing firms with more than 50 employees listed in the Spanish SABI database. Specifically, we selected firms from the most innovative Spanish industries during recent years according to the Spanish Statistical Institute (INE 2005): manufacture of machinery; manufacture of motor vehicles; manufacture of radios, TVs and telecommunications equipment; and the chemical industry. Our valid population comprised 530 firms.

As structural ambidexterity means that organisational units engaged in exploration are physically separated from those emphasising exploitation (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996), for each firm, we selected two different organisational units: production and marketing departments. Each firm was sent three different questionnaires concerning its HRM practices, HC and learning. The HR manager was asked about both production and marketing departments, while the production and marketing managers answered questions about their own department. Initially, we contacted firms by telephone before sending the questionnaires and following up. The final sample consisted of 107 firms that returned the three questionnaires completed by the HR, production and marketing managers. Our response rate was 20.18%.

To determine whether the three responses from each firm were similar, we calculated the inter-rater agreement ratio (rwg) for each of the variables in accordance with the procedures described by James and colleagues (1995). In all cases we obtained favourable values: rwg=0.90 for compensation, rwg=92 for performance appraisal, rwg=0.95 for training, rwg=0.9 for HC and rwg=0.82 and rwg=0.73 for exploitation and exploration learning respectively.

MeasurementDependent variablesWe measured organisational learning on the scales proposed by Atuaene-Gima (2005) and Lubatkin and colleagues (2006). These scales identify two dimensions for organisational learning: exploitation and exploration learning.

Financial performance was measured using the means of the last three years of ROA, ROE and profit margin. These financial variables were obtained from SABI database.

Independent and mediating variablesWe measured HC for production and marketing departments on the scales proposed by Subramaniam and Youndt (2005) and Kang and Snell (2009). These authors identified two dimensions of HC: specialist HC and generic HC. Among HRM practices, we measured compensation on the scale proposed by Gomez-Mejia (1992), and performance appraisal and training on the scales proposed by Lepak and Snell (2002). All items are measured on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7 (1=totally disagree, 7=totally agree).

Next, we measure ambidexterity following the procedures used by Edwards, Lubatkin et al. (2006) and Jansen et al. (2009) and sought the most interpretable approach for combining our measures of exploitation and exploration learning. Ambidexterity and firm performance are close linked (Birkinshaw and Gibson, 2004; He and Wong, 2004). We ran four regression analyses with a three-years ROA as the dependent variable. The first unconstrained model treats exploitative and explorative learning as separate independent variables. Then, we ran three contrained regression equations in which exploitation and exploration learning were combined into a single index, first by subtracting exploitation from exploration, second by multiplying exploration and exploitation, and third by summing the two. The goodness of fit indices shows that only the unconstrained model and the multiplying model are statistically significant. Now, we must confirm which model show a better adjustment. For this reason, we apply a χ2 test, using the programme “sbdiff.exe” developed by Satorra and Bentler (2001). The results obtained (Satorra-Bentler scaled difference=4.8839, p=0.430212) lead us to state that the multiplying model displays a better adjustment than the unconstrained model.

Control variablesWe considered firm size and department size, and activity sector. Firm size and department size variables have a great dispersion, so, in order to avoid dispersion we used natural logarithm. Firm size was measured as the natural logarithm of the number of firm employees. Department size was measured as the natural logarithm of the number of department (production or marketing) employees. Activity sector was measured by NACE classification. We selected five different activity sectors -manufacture of machinery; manufacture of motor vehicles; manufacture of radios, TVs and telecommunications equipment; and the chemical industry-, labelled from Sector 1 to Sector 5 respectively. We chose sector 1 as the reference category, which is not included in the analysis. The other categories are introduced as dummy variables.

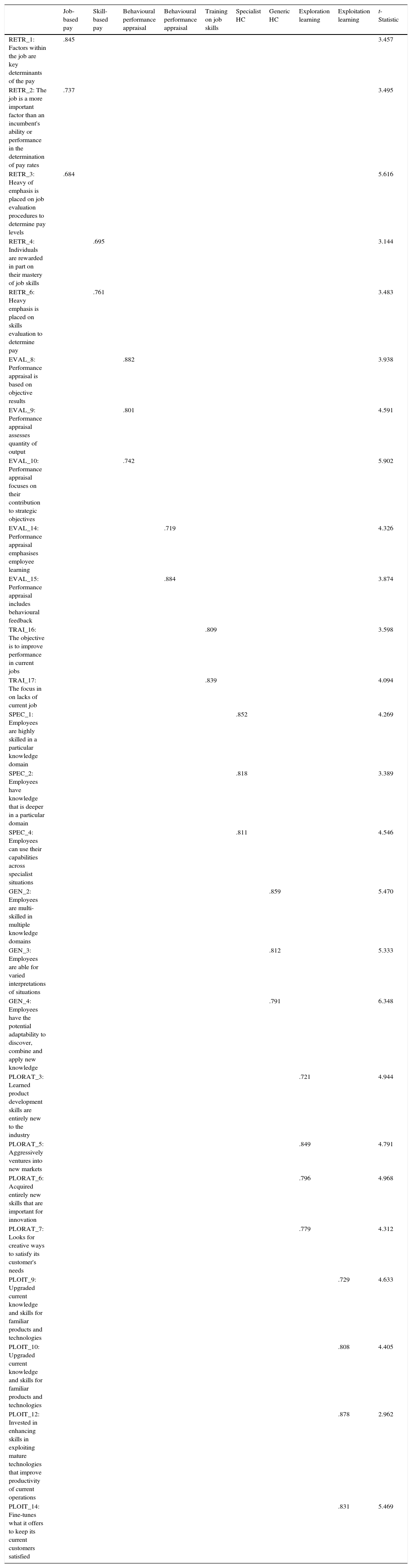

Tables 1 and 2 show the CFA standardised solution for the model, which includes HRM practices, HC and organisational learning for production departments and marketing departments respectively.

CFA (standardised solution). Production department.

| Job-based pay | Skill-based pay | Behavioural performance appraisal | Behavioural performance appraisal | Training on job skills | Specialist HC | Generic HC | Exploration learning | Exploitation learning | t-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RETR_1: Factors within the job are key determinants of the pay | .845 | 3.457 | ||||||||

| RETR_2: The job is a more important factor than an incumbent's ability or performance in the determination of pay rates | .737 | 3.495 | ||||||||

| RETR_3: Heavy of emphasis is placed on job evaluation procedures to determine pay levels | .684 | 5.616 | ||||||||

| RETR_4: Individuals are rewarded in part on their mastery of job skills | .695 | 3.144 | ||||||||

| RETR_6: Heavy emphasis is placed on skills evaluation to determine pay | .761 | 3.483 | ||||||||

| EVAL_8: Performance appraisal is based on objective results | .882 | 3.938 | ||||||||

| EVAL_9: Performance appraisal assesses quantity of output | .801 | 4.591 | ||||||||

| EVAL_10: Performance appraisal focuses on their contribution to strategic objectives | .742 | 5.902 | ||||||||

| EVAL_14: Performance appraisal emphasises employee learning | .719 | 4.326 | ||||||||

| EVAL_15: Performance appraisal includes behavioural feedback | .884 | 3.874 | ||||||||

| TRAI_16: The objective is to improve performance in current jobs | .809 | 3.598 | ||||||||

| TRAI_17: The focus in on lacks of current job | .839 | 4.094 | ||||||||

| SPEC_1: Employees are highly skilled in a particular knowledge domain | .852 | 4.269 | ||||||||

| SPEC_2: Employees have knowledge that is deeper in a particular domain | .818 | 3.389 | ||||||||

| SPEC_4: Employees can use their capabilities across specialist situations | .811 | 4.546 | ||||||||

| GEN_2: Employees are multi-skilled in multiple knowledge domains | .859 | 5.470 | ||||||||

| GEN_3: Employees are able for varied interpretations of situations | .812 | 5.333 | ||||||||

| GEN_4: Employees have the potential adaptability to discover, combine and apply new knowledge | .791 | 6.348 | ||||||||

| PLORAT_3: Learned product development skills are entirely new to the industry | .721 | 4.944 | ||||||||

| PLORAT_5: Aggressively ventures into new markets | .849 | 4.791 | ||||||||

| PLORAT_6: Acquired entirely new skills that are important for innovation | .796 | 4.968 | ||||||||

| PLORAT_7: Looks for creative ways to satisfy its customer's needs | .779 | 4.312 | ||||||||

| PLOIT_9: Upgraded current knowledge and skills for familiar products and technologies | .729 | 4.633 | ||||||||

| PLOIT_10: Upgraded current knowledge and skills for familiar products and technologies | .808 | 4.405 | ||||||||

| PLOIT_12: Invested in enhancing skills in exploiting mature technologies that improve productivity of current operations | .878 | 2.962 | ||||||||

| PLOIT_14: Fine-tunes what it offers to keep its current customers satisfied | .831 | 5.469 |

Satorra-Bentler χ2: 281.2431; p: 0.06624; BB-NFI: 0.845; BB-NNFI: 0.853; CFI: 0.889; RMSEA: 0.036.

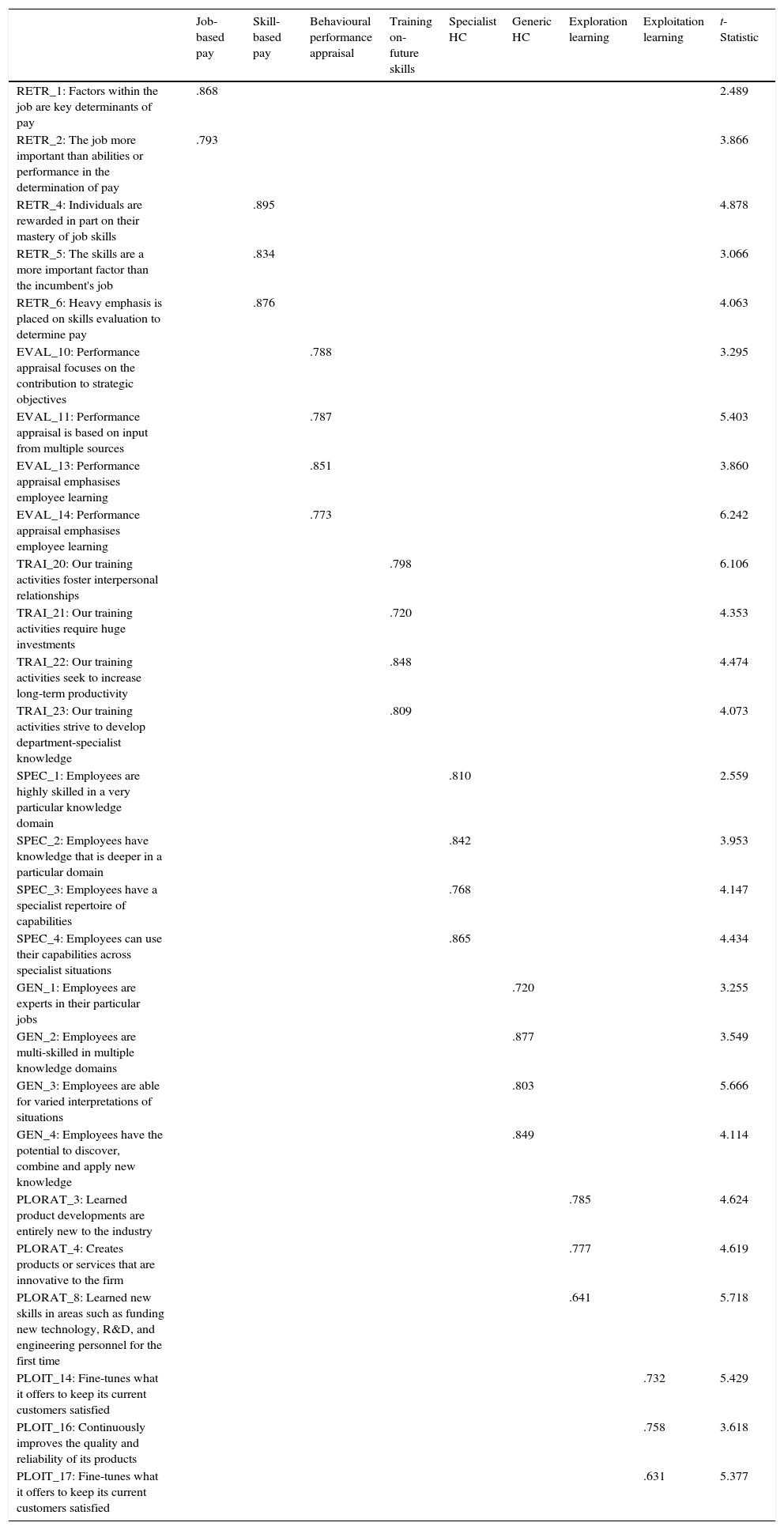

CFA (standardised solution). Marketing department.

| Job-based pay | Skill-based pay | Behavioural performance appraisal | Training on-future skills | Specialist HC | Generic HC | Exploration learning | Exploitation learning | t-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RETR_1: Factors within the job are key determinants of pay | .868 | 2.489 | |||||||

| RETR_2: The job more important than abilities or performance in the determination of pay | .793 | 3.866 | |||||||

| RETR_4: Individuals are rewarded in part on their mastery of job skills | .895 | 4.878 | |||||||

| RETR_5: The skills are a more important factor than the incumbent's job | .834 | 3.066 | |||||||

| RETR_6: Heavy emphasis is placed on skills evaluation to determine pay | .876 | 4.063 | |||||||

| EVAL_10: Performance appraisal focuses on the contribution to strategic objectives | .788 | 3.295 | |||||||

| EVAL_11: Performance appraisal is based on input from multiple sources | .787 | 5.403 | |||||||

| EVAL_13: Performance appraisal emphasises employee learning | .851 | 3.860 | |||||||

| EVAL_14: Performance appraisal emphasises employee learning | .773 | 6.242 | |||||||

| TRAI_20: Our training activities foster interpersonal relationships | .798 | 6.106 | |||||||

| TRAI_21: Our training activities require huge investments | .720 | 4.353 | |||||||

| TRAI_22: Our training activities seek to increase long-term productivity | .848 | 4.474 | |||||||

| TRAI_23: Our training activities strive to develop department-specialist knowledge | .809 | 4.073 | |||||||

| SPEC_1: Employees are highly skilled in a very particular knowledge domain | .810 | 2.559 | |||||||

| SPEC_2: Employees have knowledge that is deeper in a particular domain | .842 | 3.953 | |||||||

| SPEC_3: Employees have a specialist repertoire of capabilities | .768 | 4.147 | |||||||

| SPEC_4: Employees can use their capabilities across specialist situations | .865 | 4.434 | |||||||

| GEN_1: Employees are experts in their particular jobs | .720 | 3.255 | |||||||

| GEN_2: Employees are multi-skilled in multiple knowledge domains | .877 | 3.549 | |||||||

| GEN_3: Employees are able for varied interpretations of situations | .803 | 5.666 | |||||||

| GEN_4: Employees have the potential to discover, combine and apply new knowledge | .849 | 4.114 | |||||||

| PLORAT_3: Learned product developments are entirely new to the industry | .785 | 4.624 | |||||||

| PLORAT_4: Creates products or services that are innovative to the firm | .777 | 4.619 | |||||||

| PLORAT_8: Learned new skills in areas such as funding new technology, R&D, and engineering personnel for the first time | .641 | 5.718 | |||||||

| PLOIT_14: Fine-tunes what it offers to keep its current customers satisfied | .732 | 5.429 | |||||||

| PLOIT_16: Continuously improves the quality and reliability of its products | .758 | 3.618 | |||||||

| PLOIT_17: Fine-tunes what it offers to keep its current customers satisfied | .631 | 5.377 |

Satorra-Bentle χ2: 328.6533; p: 0.06879; BB-NFI: 0.751; BB-NNFI: 0.822; CFI: 0.852; RMSEA: 0.034.

As Table 1 shows, for production departments, five factors are obtained for HRM practices, namely job-based pay, skill-based pay, behavioural performance appraisal, developmental performance appraisal and training in job skills (t=3.716; t=2.703; t=2.693; t=2.182 and t=2.791, respectively). Two factors are related to employees’ HC: specialist HC (t=2.658) and generic HC (t=2.004). And the two dimensions of organisational learning proposed are found to be significant: exploration (t=3.244) and exploitation (t=4.122). Also, global fit indexes for CFA are included in Table 1 (Satorra-Bentler χ2: 281.2431; p: 0.06624; BB-NFI: 0.845; BB-NNFI: 0.853; CFI: 0.889; RMSEA: 0.036), in all cases those indexes show favourable values. As Table 2 shows, for marketing departments, four factors are obtained for HRM practices, namely job-based pay, skill-based pay, behavioural appraisal and training for future skills (t=3.795; t=4.947; t=3.005 and t=3.794 respectively). Two factors are related to employees’ HC: specialist HC (t=2.341) and generic HC (t=2.394). And there are two significant dimensions for organisational learning: exploration (t=4.387) and exploitation learning (t=3.870). Also, global fit indexes for CFA are included in Table 1 (Satorra-Bentle χ2: 328.6533; p: 0.06879; BB-NFI: 0.751; BB-NNFI: 0.822; CFI: 0.852; RMSEA: 0.034), in all cases those indexes show favourable values. For each factor, indicators are included only if the estimated parameters are significant with high factor loadings; thus some of the items of the original scales were eliminated.

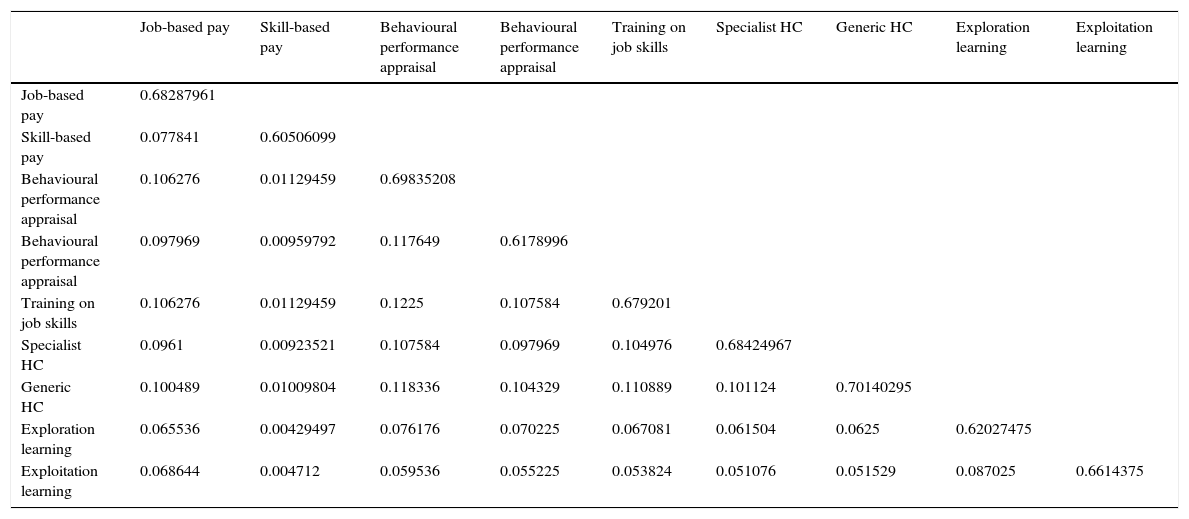

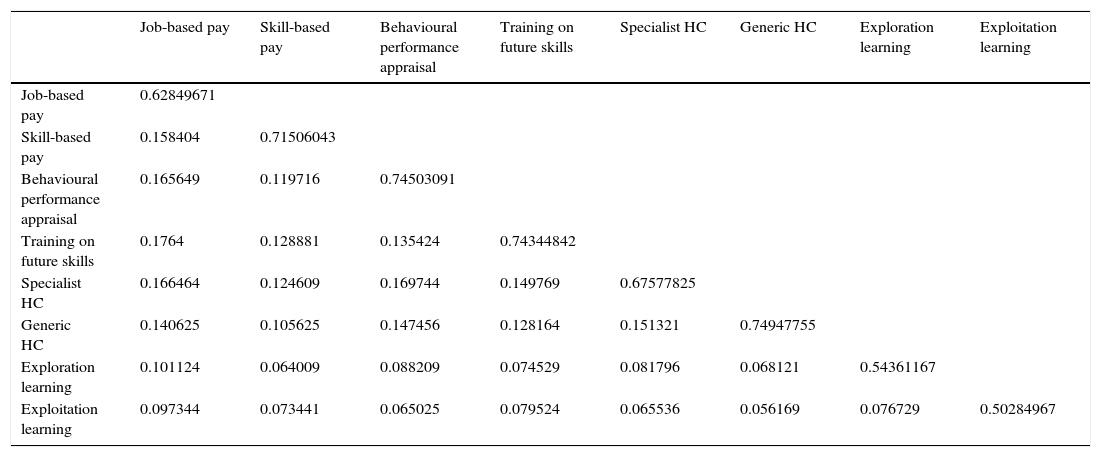

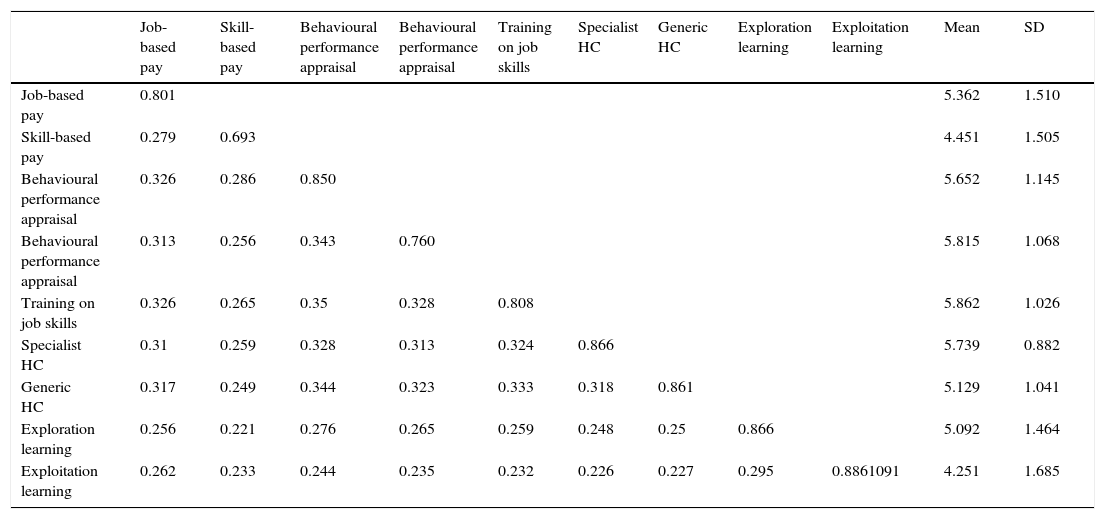

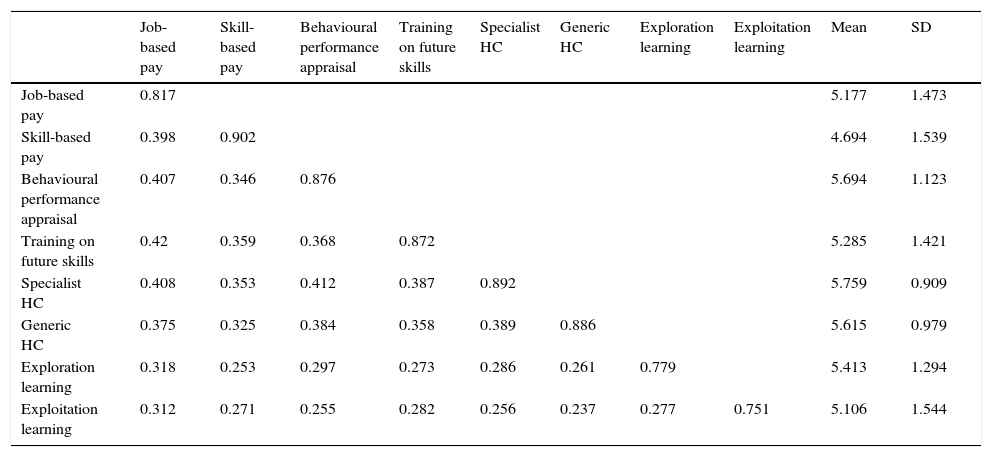

We concluded from Tables 3 and 4 that the scales are reliable and that convergent and discriminant validities exist in both groups of departments. The reliability of the scales is measured by the composite reliability value, which in all cases was greater than or equal to 0.7. Convergent validity is confirmed by the average variance extracted, which in all cases was greater than 0.5. Discriminant validity is also confirmed: the mean variance extracted (principal diagonal) is higher than the square of the correlations between factors.

Discriminant validity for production department.

| Job-based pay | Skill-based pay | Behavioural performance appraisal | Behavioural performance appraisal | Training on job skills | Specialist HC | Generic HC | Exploration learning | Exploitation learning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job-based pay | 0.68287961 | ||||||||

| Skill-based pay | 0.077841 | 0.60506099 | |||||||

| Behavioural performance appraisal | 0.106276 | 0.01129459 | 0.69835208 | ||||||

| Behavioural performance appraisal | 0.097969 | 0.00959792 | 0.117649 | 0.6178996 | |||||

| Training on job skills | 0.106276 | 0.01129459 | 0.1225 | 0.107584 | 0.679201 | ||||

| Specialist HC | 0.0961 | 0.00923521 | 0.107584 | 0.097969 | 0.104976 | 0.68424967 | |||

| Generic HC | 0.100489 | 0.01009804 | 0.118336 | 0.104329 | 0.110889 | 0.101124 | 0.70140295 | ||

| Exploration learning | 0.065536 | 0.00429497 | 0.076176 | 0.070225 | 0.067081 | 0.061504 | 0.0625 | 0.62027475 | |

| Exploitation learning | 0.068644 | 0.004712 | 0.059536 | 0.055225 | 0.053824 | 0.051076 | 0.051529 | 0.087025 | 0.6614375 |

Discriminant validity for marketing department.

| Job-based pay | Skill-based pay | Behavioural performance appraisal | Training on future skills | Specialist HC | Generic HC | Exploration learning | Exploitation learning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job-based pay | 0.62849671 | |||||||

| Skill-based pay | 0.158404 | 0.71506043 | ||||||

| Behavioural performance appraisal | 0.165649 | 0.119716 | 0.74503091 | |||||

| Training on future skills | 0.1764 | 0.128881 | 0.135424 | 0.74344842 | ||||

| Specialist HC | 0.166464 | 0.124609 | 0.169744 | 0.149769 | 0.67577825 | |||

| Generic HC | 0.140625 | 0.105625 | 0.147456 | 0.128164 | 0.151321 | 0.74947755 | ||

| Exploration learning | 0.101124 | 0.064009 | 0.088209 | 0.074529 | 0.081796 | 0.068121 | 0.54361167 | |

| Exploitation learning | 0.097344 | 0.073441 | 0.065025 | 0.079524 | 0.065536 | 0.056169 | 0.076729 | 0.50284967 |

We use structural equation modelling to test the hypotheses of this study. Tables 5 and 6 show that the scales are reliable and that structural equation modelling can be applied in production and marketing departments respectively.

Means, standard deviations, correlations and composite reliability (production department).

| Job-based pay | Skill-based pay | Behavioural performance appraisal | Behavioural performance appraisal | Training on job skills | Specialist HC | Generic HC | Exploration learning | Exploitation learning | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job-based pay | 0.801 | 5.362 | 1.510 | ||||||||

| Skill-based pay | 0.279 | 0.693 | 4.451 | 1.505 | |||||||

| Behavioural performance appraisal | 0.326 | 0.286 | 0.850 | 5.652 | 1.145 | ||||||

| Behavioural performance appraisal | 0.313 | 0.256 | 0.343 | 0.760 | 5.815 | 1.068 | |||||

| Training on job skills | 0.326 | 0.265 | 0.35 | 0.328 | 0.808 | 5.862 | 1.026 | ||||

| Specialist HC | 0.31 | 0.259 | 0.328 | 0.313 | 0.324 | 0.866 | 5.739 | 0.882 | |||

| Generic HC | 0.317 | 0.249 | 0.344 | 0.323 | 0.333 | 0.318 | 0.861 | 5.129 | 1.041 | ||

| Exploration learning | 0.256 | 0.221 | 0.276 | 0.265 | 0.259 | 0.248 | 0.25 | 0.866 | 5.092 | 1.464 | |

| Exploitation learning | 0.262 | 0.233 | 0.244 | 0.235 | 0.232 | 0.226 | 0.227 | 0.295 | 0.8861091 | 4.251 | 1.685 |

The values in the diagonal are the composite reliability of each factor.

Means, standard deviations, correlations and composite reliability (marketing department).

| Job-based pay | Skill-based pay | Behavioural performance appraisal | Training on future skills | Specialist HC | Generic HC | Exploration learning | Exploitation learning | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job-based pay | 0.817 | 5.177 | 1.473 | |||||||

| Skill-based pay | 0.398 | 0.902 | 4.694 | 1.539 | ||||||

| Behavioural performance appraisal | 0.407 | 0.346 | 0.876 | 5.694 | 1.123 | |||||

| Training on future skills | 0.42 | 0.359 | 0.368 | 0.872 | 5.285 | 1.421 | ||||

| Specialist HC | 0.408 | 0.353 | 0.412 | 0.387 | 0.892 | 5.759 | 0.909 | |||

| Generic HC | 0.375 | 0.325 | 0.384 | 0.358 | 0.389 | 0.886 | 5.615 | 0.979 | ||

| Exploration learning | 0.318 | 0.253 | 0.297 | 0.273 | 0.286 | 0.261 | 0.779 | 5.413 | 1.294 | |

| Exploitation learning | 0.312 | 0.271 | 0.255 | 0.282 | 0.256 | 0.237 | 0.277 | 0.751 | 5.106 | 1.544 |

The values in the diagonal are the composite reliability of each factor.

We performed a cluster analysis and an ANOVA in order to identify whether there are significant differences in firm performance between ambidextrous firms and those that pursue only exploration or only exploitation learning. Results show that the means of ROE, ROA and profit margin are, in all cases, higher for ambidextrous firms (ROE=5.3, ROA=2.16, profit margin: 2.95) than for non-ambidextrous firms (ROE=−5.5, ROA=1.83, profit margin: −2.20). So our Hypothesis 1 is supported.

In order to test Hypothesis 2, we performed a cluster analysis and an ANOVA to identify the proportions of production and marketing departments in our sample that carry out exploitation and exploration learning. Among production departments, we identified 91 (84.25%) pursuing exploitation learning and 17 (15.74%) pursuing exploration learning. Among marketing departments, 38 (35.18%) carry on exploitation learning and 70 (64.82%) pursue exploration learning. These findings show that production departments are mainly exploitative departments while marketing departments are mainly exploratory departments and thus support Hypothesis 2.

Structural ambidexterity captures coordination between departments. We measured coordination by three items: ‘the production and marketing departments are coordinated by their managers’, ‘there are coordination meetings with employees from production and marketing departments regularly’ and ‘production and marketing departments work regardless of each other but a certain degree of integration is needed’ (α=0.873). The results show that coordination rwg=0.862; mean=5.9 and SD=1.115. That is, the firms in our sample have some type of coordination between exploitative and exploratory departments.

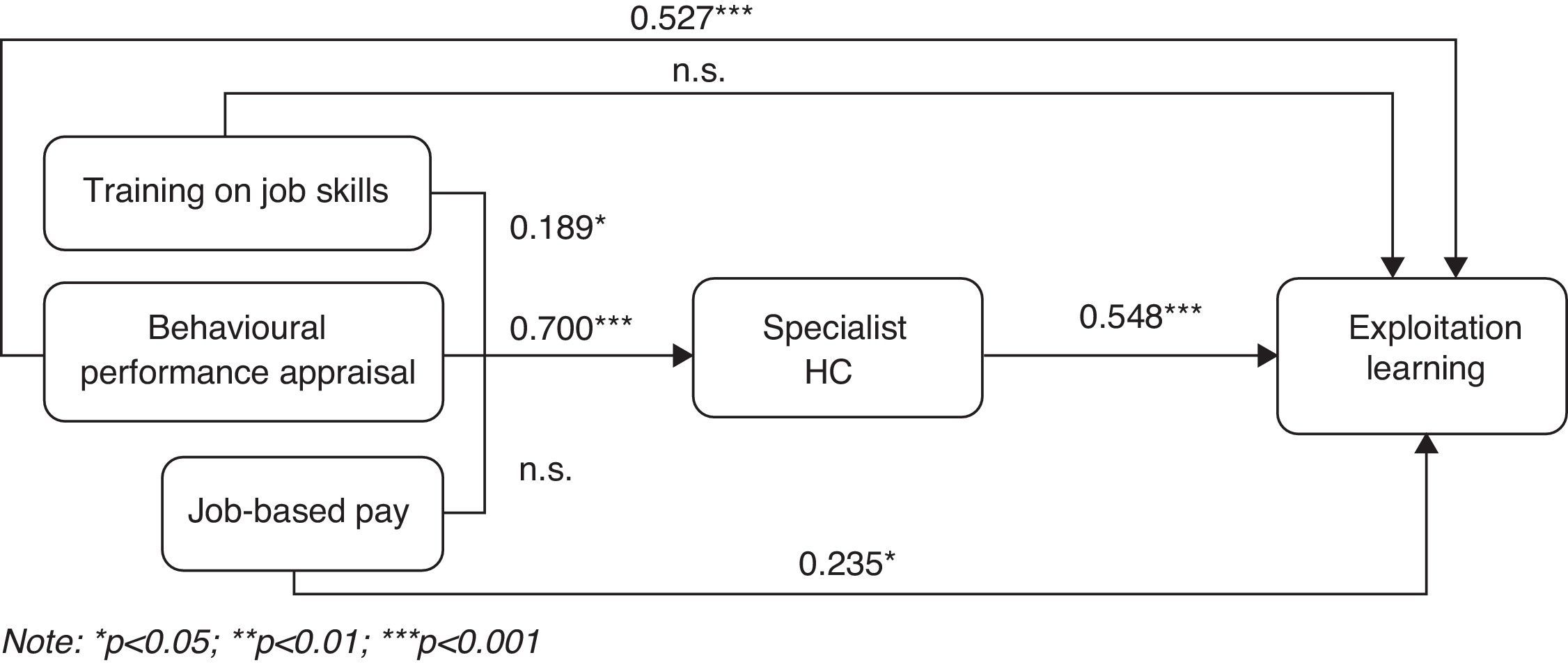

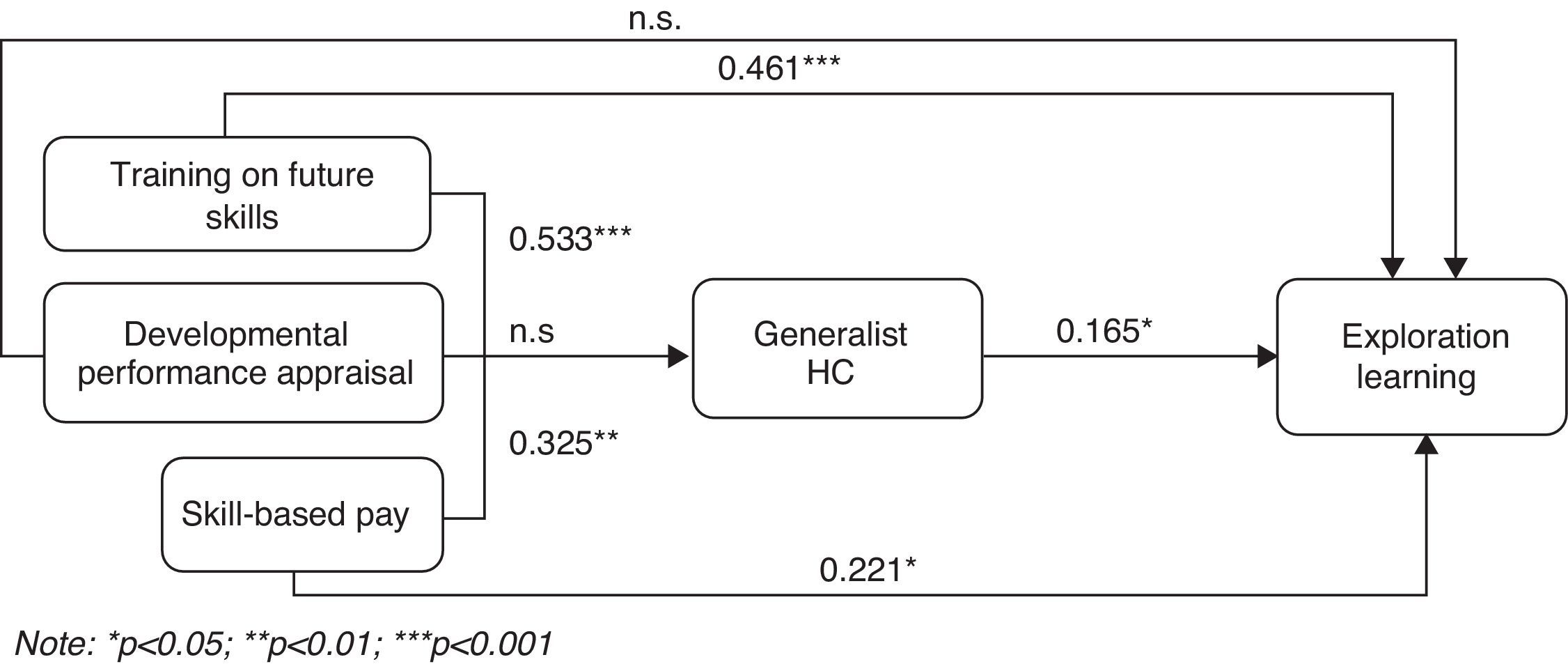

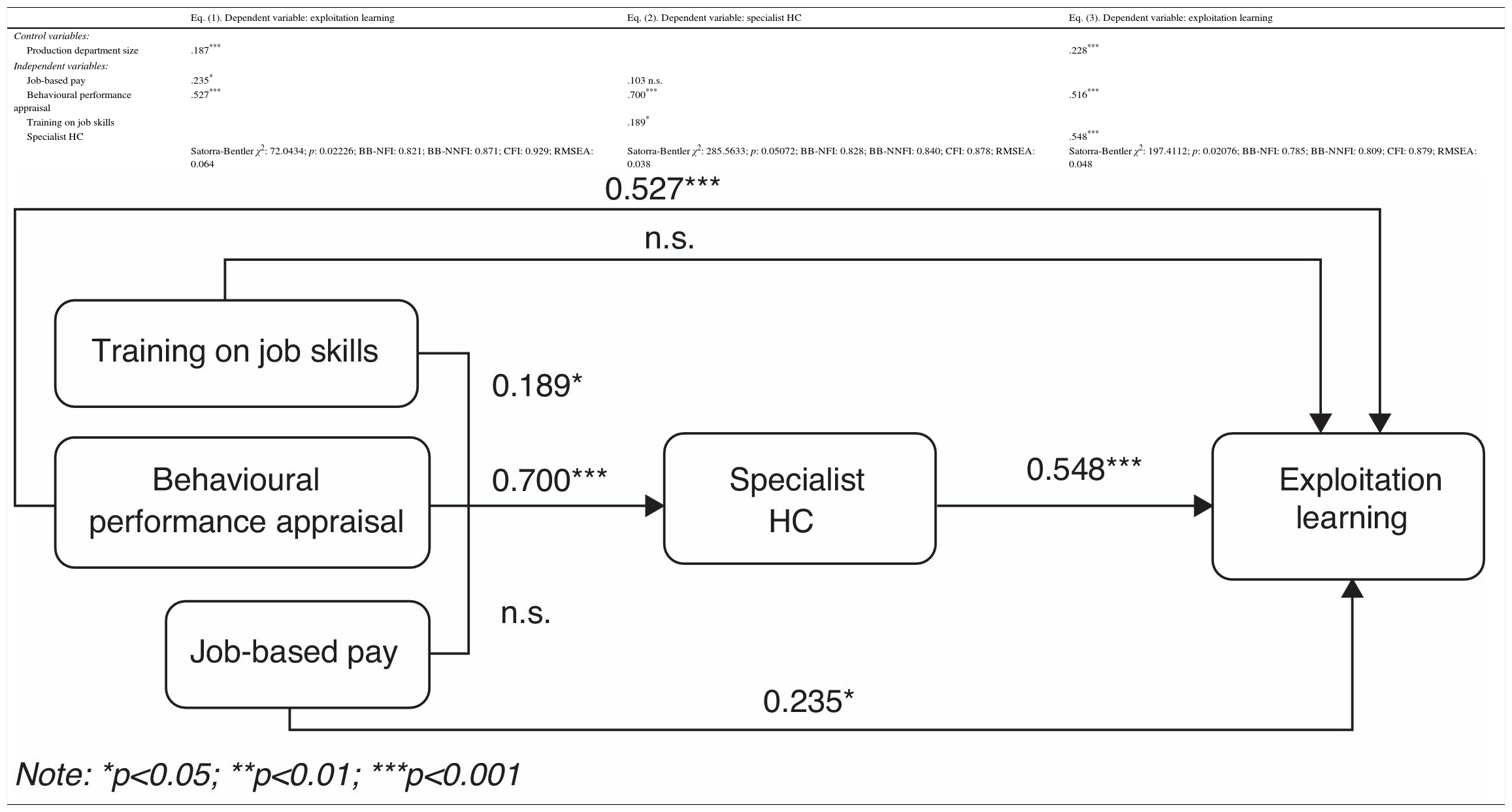

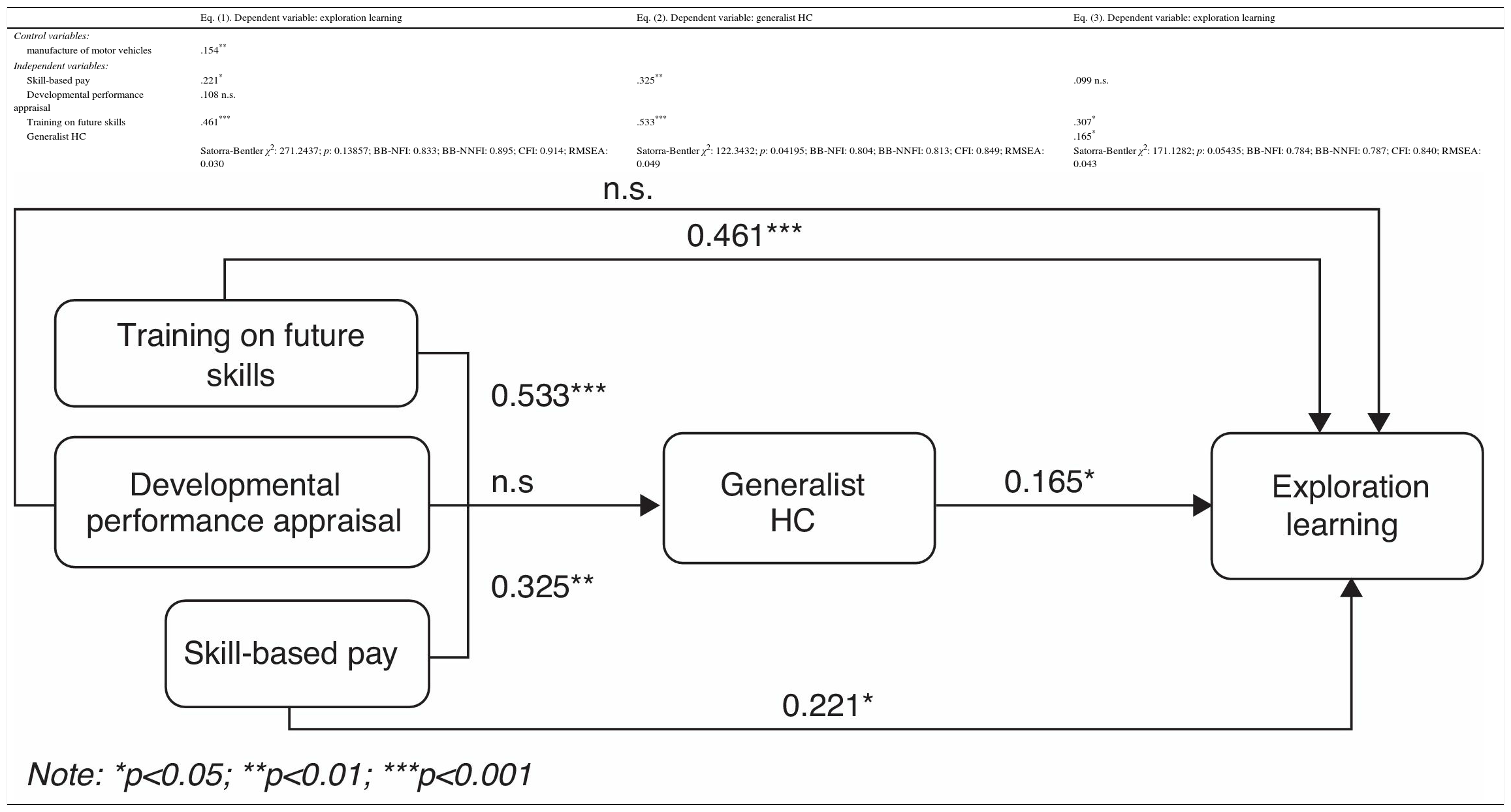

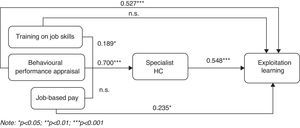

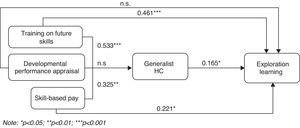

Our findings also show that specialist HC is directly associated with exploitation learning (Eq. (3) in Table 7) and generalist HC is positively related to exploration learning (Eq. (3) in Table 8). Thus Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Results for production department.

| Eq. (1). Dependent variable: exploitation learning | Eq. (2). Dependent variable: specialist HC | Eq. (3). Dependent variable: exploitation learning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables: | |||

| Production department size | .187*** | .228*** | |

| Independent variables: | |||

| Job-based pay | .235* | .103 n.s. | |

| Behavioural performance appraisal | .527*** | .700*** | .516*** |

| Training on job skills | .189* | ||

| Specialist HC | .548*** | ||

| Satorra-Bentler χ2: 72.0434; p: 0.02226; BB-NFI: 0.821; BB-NNFI: 0.871; CFI: 0.929; RMSEA: 0.064 | Satorra-Bentler χ2: 285.5633; p: 0.05072; BB-NFI: 0.828; BB-NNFI: 0.840; CFI: 0.878; RMSEA: 0.038 | Satorra-Bentler χ2: 197.4112; p: 0.02076; BB-NFI: 0.785; BB-NNFI: 0.809; CFI: 0.879; RMSEA: 0.048 | |

Results for marketing department.

| Eq. (1). Dependent variable: exploration learning | Eq. (2). Dependent variable: generalist HC | Eq. (3). Dependent variable: exploration learning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables: | |||

| manufacture of motor vehicles | .154** | ||

| Independent variables: | |||

| Skill-based pay | .221* | .325** | .099 n.s. |

| Developmental performance appraisal | .108 n.s. | ||

| Training on future skills | .461*** | .533*** | .307* |

| Generalist HC | .165* | ||

| Satorra-Bentler χ2: 271.2437; p: 0.13857; BB-NFI: 0.833; BB-NNFI: 0.895; CFI: 0.914; RMSEA: 0.030 | Satorra-Bentler χ2: 122.3432; p: 0.04195; BB-NFI: 0.804; BB-NNFI: 0.813; CFI: 0.849; RMSEA: 0.049 | Satorra-Bentler χ2: 171.1282; p: 0.05435; BB-NFI: 0.784; BB-NNFI: 0.787; CFI: 0.840; RMSEA: 0.043 | |

Next, to verify the existence of mediator effects of HC on the relationship between HRM practices and organisational learning, we used the method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), which consists of estimating three models:

Four conditions must obtain: in Eqs. (1) and (2), the independent variable must be significant; in Eq. (3), the mediator variable must be significant and the independent variable must be lower (in absolute terms) than in Eq. (1).

Tables 7 and 8 show the results for regressions that consider independent variables and mediators together for production and marketing departments respectively. The pattern of coefficients related to HRM practices, HC and learning fulfils all the conditions (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Therefore, the results initially indicate that HC mediates the relationships between HRM practices and learning. Specifically, in production departments (Table 7), the relationship between behavioural performance appraisal and exploitation learning is mediated by specialist HC. In this case, the control variable department size is also significant. In marketing departments (Table 8), generalist HC mediates the relationship between training for future skills and exploration learning. Thus Hypothesis 4 is partially supported.

Finally, our results partially support Hypotheses 4.1 and 4.2. In production departments, we found empirical support for the relationships between behavioural performance appraisal and job-based compensation and exploitative learning, but not between these two practices and training and development in job-related skills (Eq. 1 in Table 7). In marketing departments skill-based pay and training for future skills are directly and positively related to exploration learning but training and development for future skills is not linked to exploratory learning (Eq. (1) in Table 8). Some control variables affected these relationships—specifically, department size was important for production departments, and sector (manufacture of motor vehicles) was important for marketing departments.

With respect to the relationships between HC and HRM practices, the results show that in production departments (Eq. (2) in Table 7) specialist HC is fostered by training and development in job-related skills and job-based pay but not by behavioural performance appraisal. In marketing departments, skill-based pay and training for future skills are positively associated with generalist HC (Eq. (2) in Table 8) but not with developmental performance appraisal. Thus Hypotheses 4.1 and 4.2 are also partially supported.

ConclusionsOur results reveal the structural nature of ambidexterity in firms and the existence of coordination mechanisms. Specifically, we found that exploitation learning is related to production units and exploration learning is associated with marketing units. These differences in learning result from differences in activities. The ambidexterity of the organisation depends on the existence of these different units focusing on diverse learning, but also on promoting connection between them. In our sample, this coordination between organisational units is shown through interdepartmental relationships between department managers as well as periodic meetings between production and marketing units (the coordination factor mean is 5.9 out of 7), a pattern that is confirmed by the acceptable level of agreement about these coordination mechanisms among our three respondents (rwg=0.89).

Our results have confirmed that different departments and different types of learning require different types of HC. Specialist HC is present in production departments and is related to exploitation learning, and generalist HC is present in marketing departments and is related to exploration learning. Therefore, the type of learning an organisation can do depends on its HC composition.

Our results show that the HRM practices of training and development, performance appraisal and compensation are oriented towards different types of HC and learning. Behavioural performance appraisal and job-based pay are the most relevant practices for exploitative learning. Training in job skill seems to have no effect, but this may be because it works through the other two practices. In contrast, training for future skills and skill-based pay are significant for exploratory learning. HRM practices also differ in the influence that they exert on HC and on learning. In production departments performance appraisal is the most relevant HR practice; in marketing departments, where innovation and new learning are vital, training is most significant. Hence, we conclude that there is no single model for HRM best practice, but rather different HRM best practice models within an organisation.

We found that in different organisational units, different types of human capital mediate the relationship between different HRM practices and different types of learning. In production departments specialist HC mediates the relationship between performance appraisal and exploitation learning; in marketing departments, generalist HC mediates the relationship between training and exploration learning. This finding should be explored more deeply in future research. Among our control variables, size is significant in production departments and activity sector in marketing departments, probably because of their external orientation.

We can highlight some implications for practitioners. First, the need to consider that there must be an adjustment between the role played by each department and the kind of learning that must be driven into it. Diversity and differentiation between units leads to the need to combine different organisation types of learning. A second practical implication is that the learning required demands a particular type of HC, with a particular knowledge since it is this which enables learning. This should be taken into consideration in the design of training programmes, and even in the recruitment process. The third implication that emerges from the paper is that the management of HR should not be homogeneous as these organisations should encourage different behaviours depending on the characteristics of the employees and the kind of learning that the unit requires. Therefore, depending on the predominant approach to learning in a department, managers should design different HRM practices and promote diverse HC. Again, no single HRM practice or HC model should be considered for all organisational departments.

This paper has some limitations that point to new research lines. Our first limitation is related to the population selected: we have considered only innovative activity sectors, which could bias the results. Second, coordination mechanisms may require more attention and an in-depth analysis, as they may help to explain the role of other variables considered in this study. It should be interesting analysing its effect on ambidexterity and its relationship with outcomes such as a better performance. Third, it might be interesting to consider other HRM practices. Job characteristics are another variable that might explain the relationships analysed in this paper. Lastly, the possibility that the environment moderates some of our results could be addressed in our future research. The more dynamic and complex environmental conditions may explain different configurations of HC and learning. Highly innovative environments can differ in their demands, and companies may adapt their HC, learning and HR practices to comply with these requirements.

Financial support for this article was provided by the Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad, Plan Nacional de I+D+I (ECO2010-14939).