The aim of this study is to investigate the entrepreneurial process of new venture creation through a psychoanalytic approach. Building upon existing psychoanalytic literature, the manuscript proposes a framework for explaining the entrepreneurial process that results in individuals forming ideas for new venture creation. The framework is composed of a set of interrelated processes explaining entrepreneurial behaviour through the identification of three stages: dream, business idea, and new venture creation. Though it acknowledges previous managerial and organizational literature, this paper focuses more on “the dark side” of the entrepreneurial process by stressing the unconscious mechanisms that encourage new business ventures. The proposed framework provides a more detailed understanding of entrepreneurs’ actions and offers new insights into the evolution of the entrepreneurial process.

This study is an attempt at providing a psychoanalytic interpretation of the entrepreneurial process for new venture creation. It focuses on the persona of the entrepreneur in order to understand the foundations of convictions and beliefs in the process of business idea generation. Entrepreneurship is a key topic in the existing literature on management, which includes new venture creation, revitalizing mature organizations, and exploiting market opportunities through technical and/or organizational innovations (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Similarly, Zahra and Dess (2001) argue that entrepreneurship also exists within organizations in the form of corporate venturing, strategic renewal, and ideas generated within organizations. Other scholars have focused on a more comprehensive definition of entrepreneurship that also includes accidental or end-user entrepreneurs (Cuomo, Tortora, Festa, Giordano, & Metallo, 2017). It should be noted that the concept of entrepreneurship has a broad meaning, so much so that various frameworks have been developed to explain the concept over time (Shane, 2012). Consistent with prior contributions on entrepreneurship as an individual phenomenon (e.g., Kuratko, Morris, & Schindehutte, 2015; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), the research aims to explain the entrepreneurial process of new venture creation by stressing the unconscious mechanisms that govern entrepreneurs’ behaviours.

An entrepreneur is an innovative and creative person who explores environment for new opportunities and takes advantage of them after proper evaluation. These opportunities also concern the creation of new ventures, which is a central topic in entrepreneurial debates. New venture creation is the creation of new organizations through planning, organizing, and establishing them (Gartner, 1985).

The importance of understanding entrepreneurs and their mental processes has been widely recognized (Shaver & Scott, 1991), especially as the new venture creation process does not always seem to follow rational patterns of behaviour (e.g., Baron, 2007; Cardon, Wincent, Singh, & Drnovsek, 2009; Foo, Uy, & Baron, 2009). The psychological approach to new venture creation stresses the process through which the external world becomes represented in the mind (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Shaver & Scott, 1991). Such an approach does not consider organizational members to be rational beings, but rather individuals are driven by unconscious desires, emotions, and fantasies (Gabriel & Carr, 2002). According to Akey, Dai, Torku, and Adu (2017), these unconscious ideas and desires can significantly contribute to emotional obstacles that are seen in organizations, such as envy, ambition, failure, fear, and rejection. Therefore, a psychoanalytic approach can provide insight into the nature of “irrational” behaviour at all levels of an organization (Akey et al., 2017). Kets de Vries (2004) argued that unconscious stimuli are a regular feature of daily organizational behaviours. “We all have a dark side—a side that we don’t know (and don’t want to know)” (Kets de Vries, 2004, p. 187).

Some scholarship has shown the explanatory power of the psychoanalytic view in studying organizational and managerial issues (e.g., Arnaud, 2012; Arnaud & Vanheule, 2013; Arnaud & Vidaillet, 2018; Driver, 2017a; 2017b; Fotaki, Long, & Schwartz, 2012; Vidaillet, 2007). According to the psychoanalytic view, running a business is not necessarily a rational process. In many cases, such process appears to be a retrospective “rationalizing” of decisions already made unconsciously by the entrepreneur (Kets de Vries, 1996). Thus, business ideas and new venture creation can be considered the outputs of a process that emphasizes the “dark side” of entrepreneurial behaviour, combining the unconscious, desires, dreams, and fantasies.

The application of concepts that are derived from psychoanalysis to the entrepreneurial process allows us to better understand the functioning mechanisms of individuals within an organization.

Previous studies have described organizations as the result of conscious and unconscious entrepreneurial dreams (e.g., Ulrich, 2007). “These dreams often deal with the implicit challenges we face and give our mind a way to ponder those challenges and concoct ways to deal with them through our dreams” (Ulrich, 2007, p. 1). A business can be considered the translation of a dream into reality, where the entrepreneur’s dream plays a critical role in the business’ success (Francois, 2011).

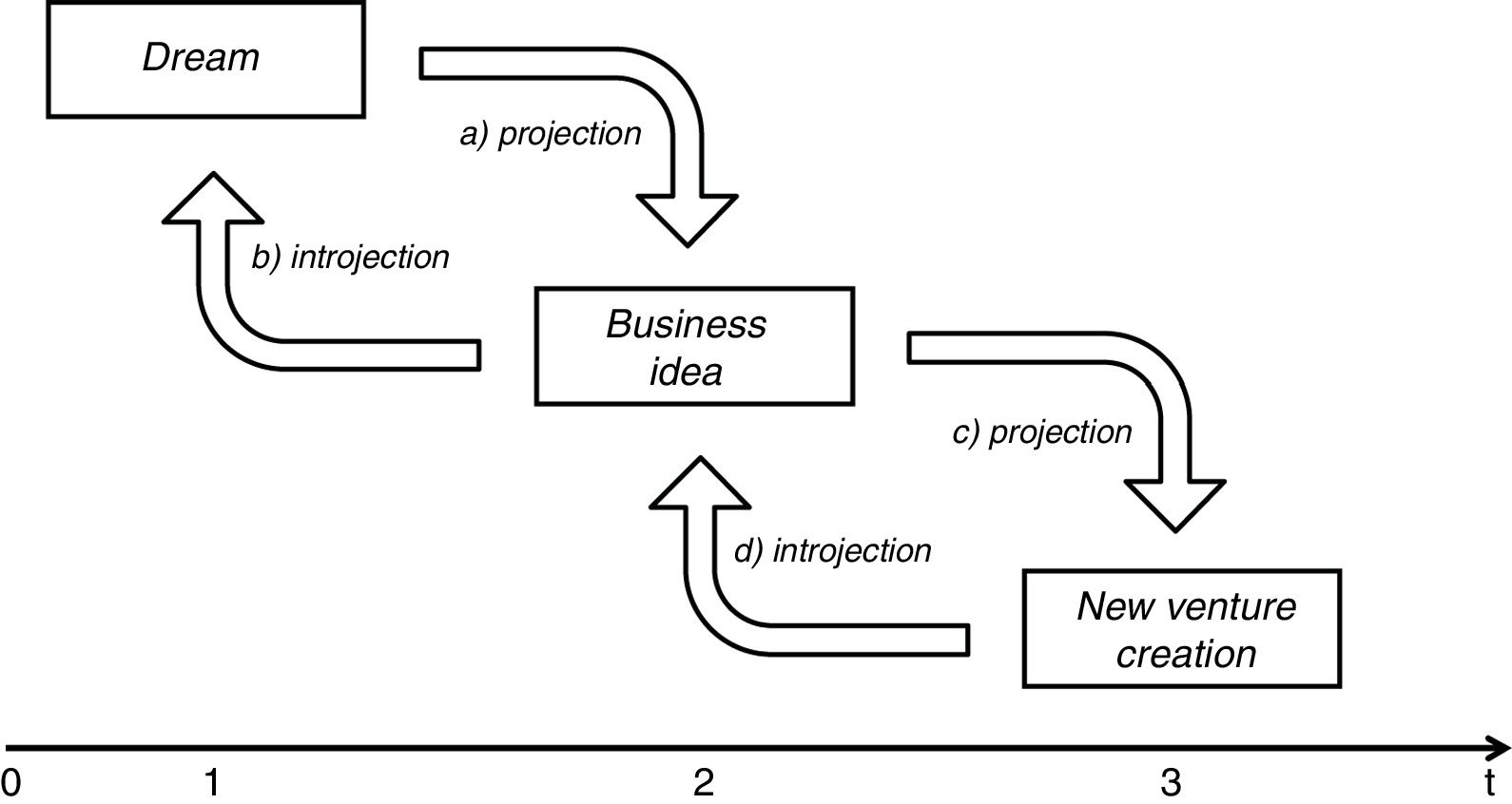

In this study, through the concept of dreams and psychoanalytic mechanisms of projection and introjection, a conceptual framework is developed that emphasizes a set of interrelated processes, which can help explain the entrepreneurial process. In this way, the entrepreneurial process can be considered the projection of the conscious and unconscious dreams of the entrepreneur, through which they formulate and realize business ideas through new venture creation. At the same time, beliefs, values, and symbols absorbed through the environment or the collective unconscious (introjection) play a role in guiding this process.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it reviews the managerial literature on business ideas to highlight the main factors that lead people toward realization. Next, it explores the psychoanalytic concepts of dreams, projection, and introjection. Then, it presents a conceptual framework for understanding the entrepreneurial process before reaching a conclusion.

The entrepreneurial processIn recent decades, entrepreneurship has emerged as one of the most promising fields of scholarly inquiry. Although the academic literature recognizes the importance of entrepreneurship, it is difficult to find a commonly agreed theoretical framework to explain the phenomenon. As Shane (2012) noted, the very definition of “entrepreneurship” remains widely contested. Consistent with prior research on entrepreneurship as an individual-level phenomenon, the research focuses on the topic of new venture creation, which is widely recognized as an integral part of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship deals with various facets of new venture creation, such as new venture ideas, evaluation, and exploitation for value creation (Kuratko et al., 2015; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000).

Many of the most important issues in entrepreneurship and business venturing stem from a seemingly simple question: “How does an entrepreneur create a venture?” The literature is not in agreement on the factors that lead people to establish new entrepreneurial initiatives, and different approaches to explaining the phenomenon have been proposed (Kuratko et al., 2015; Salamzadeh, 2015; Shook, Priem, & McGee, 2003; Simpeh, 2011).

More generally, the theory that attempts to explain new venture creation is based on several academic disciplines. Simpeh (2011) proposed a more comprehensive summary review of entrepreneurship by identifying six theories that attempt to explain the phenomenon over time. These are: economic entrepreneurship theory; opportunity-based entrepreneurship theory; resource-based entrepreneurship theory; sociological entrepreneurship theory; anthropological entrepreneurship theory; and psychological entrepreneurship theory.

Economic theories of entrepreneurship consider the creation of a new venture to be an entrepreneur’s main contribution (Schumpeter, 1934). Economic entrepreneurship theory attempts to explain entrepreneurial behaviour by using an outcome-based approach, which is focused on the economic benefits that cause human action. In contrast to classical and neoclassical theories, the Austrian School of Economics’ thinking is closest to the entrepreneur’s contribution to the formation of new ventures. In such regard, entrepreneurship seems to be viewed as the result of the motivations and actions of individuals (Low & MacMillan, 1988; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005).

Building upon classical and neoclassical economic theories and the Austrian School of Economics’ thinking, opportunity-based entrepreneurship theory and resource-based entrepreneurship theory have provided a wide-ranging conceptual framework for entrepreneurship research (Drucker, 1985; Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990). The first approach views an entrepreneur as a person who does not cause change but rather exploits the opportunities that change creates (Drucker, 1985). The latter sees a firm’s resources (financial, social, and human) as critical factors in new venture formation (Aldrich, 1999).

Sociological theories of entrepreneurship posit social context as the driving force of entrepreneurship (Landstrom, 1998; Reynolds, 1991; Ulhøi, 2005). This approach sees external stimuli, such as social relationships and the wider environment as critical push factors in determining an entrepreneur’s behaviours and chosen initiatives.

Anthropological theories of entrepreneurship instead focusing on the cultural forces impacting an individual’s attitudes and behaviours. This approach places entrepreneurship within the context of culture and examines how it reflects ethnic, social, economic, ecological, and political complexities (Mitchell, Smith, Morse, Seawright, Peredo, & McKenzie, 2002). Thus, differing cultural environments produce differences in entrepreneurs’ attitudes and behaviours (Shane & Eckhardt, 2003).

Furthermore, psychological theories of entrepreneurship focus on personal characteristics that define entrepreneurs’ behaviours. These studies attempt to link behaviourist approaches and new venture formation research in order to enhance the academic understanding of an entrepreneur’s behaviour. Although early psychological research into entrepreneurship has focused on personality traits, the need for achievement and the locus of control, which were recognized in explaining individual behaviour with reference to new venture formation (Simpeh, 2011), more recent research has taken a different approach, known as cognitive psychology or entrepreneurial cognition, which focuses on the entrepreneur’s cognitive style (Allison, Chell, & Hayes, 2000; Baron, 1998, 2007; Chaston & Sadler-Smith, 2012; Mitchell et al., 2002). Cognitive style is defined as a person’s preferred way of gathering, processing, and evaluating information (Allison et al., 2000). In this respect, cognitive style research in the field of management tries to offer an increased understanding of the link between an entrepreneur’s stimuli and responses using cognitive explanations offered by information processing. While the central research questions in entrepreneurial cognition research have historically been “how do entrepreneurs think?” and “why do they do some of the things they do?”, more recent research has focused on developing explanations that are interactive and contextualized, emphasizing socially situated cognition (Mitchell, Randolph-Seng, & Mitchell, 2011; Smith & Semin, 2004).

With respect to Simpeh’s (2011) classification, other research has also stressed the link between psychoanalytic perspective and managerial literature, with particular reference to organizational theory, organizational behaviour, and entrepreneurship issues (Akey et al., 2017; Baldacchino, Ucbasaran, Cabantous, & Lockett, 2015; Brown, Mcdonald, & Smith, 2013; Driver, 2008; Gabriel & Carr, 2002; Gabriel, 2012; Jones & Spicer, 2005; Kets de Vries, 1996). It should be noted that although some psychoanalytic concepts have filtered into wider discourses around organizations, these notable contributions are still localized (Gabriel, 2012).

Gabriel and Carr (2002) distinguished between two contrasting psychoanalytic perspectives on organizations, namely “studying organizations psychoanalytically”, which looks at organizations as dominant elements of society and culture and focuses on how they influence individuals, interpersonal relations, and people’s emotional lives and dreams, and “psychoanalyzing organizations”, which seeks to psychoanalyze organizations as though they are ailing patients. Other research, instead, has sought to combine the two approaches, using early theories of psychoanalysis to shift the normal and pathological traits of individuals to organizations and vice versa (Gabriel, 2012).

Consistent with the second and third perspectives, research on psychoanalytic thinking in the field of management has mainly focused on individual and social dimensions of unconscious life in entrepreneurial processes (Akey et al., 2017; Baldacchino et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2013; Driver, 2008; Jones & Spicer, 2005; Kets de Vries, 1996). Building upon early theories of psychoanalysis, some research has explored entrepreneurs’ behaviours in terms of work (Kets de Vries, 1996), intuition (Baldacchino et al., 2015), creativity (Driver, 2008), and leadership (Akey et al., 2017). Others have instead explored entrepreneurial processes in terms of organizational identity and cultural change (Brown et al., 2013), and analysed the sublime object of entrepreneurship (Jones & Spicer, 2005).

A psychoanalytic view of new venture creationThe potential of psychoanalytic contributions to the study of organizations and managerial issues has attracted the attention of various scholars (e.g., Akey et al., 2017; Arnaud, 2012; Baldacchino et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2013; Driver, 2008; Fotaki et al., 2012; Gabriel & Carr, 2002; Jones & Spicer, 2005; Kets de Vries, 1996), giving rise to a field of management study that emphasizes the “dark side” of entrepreneurs’, managers’ or workers’ behaviours (Kets de Vries, 1985).

The psychoanalytic view allows scholars to combine unconscious, interpersonal, and intrapsychic processes with corporate issues and organizational dynamics (Arnaud & Vanheule, 2013). This allows a deepening understanding of the underlying dynamics or “dark sides” of formal organizations (Willcocks & Rees, 1995). Thus, the unconscious forces that motivate members can be understood in the context of the organization and individuals’ social environment (Neumann & Hirschhorn, 1999).

Today, concepts such as the unconscious, desires, dreams, fantasies, and the mind are increasingly used to explore topics related to leadership, learning, motivation at work, power, change, entrepreneurial processes, and public management issues. For a review, see Arnaud (2012) and Fotaki et al. (2012).

Many studies focusing on psychoanalytic approaches to work and organizations date back six decades and gained prominence in the 1980s (Arnaud, 2012). For example, the psychoanalytic approach is used by Diamond (1986) in analysing organizational change. Schneider and Dunbar (1992) developed a psychoanalytic reading of hostile takeovers between organizations in an attempt to explore the deeper meanings of these events. Barabasz (2014) analysed the human capital of an organization from a psychoanalytic perspective, showing the main psychological mechanisms that influence the organization’s formation and development. Some scholars (Driver, 2008; Schiavone & Villasalero, 2013) have taken a psychoanalytic view of creativity in organizations. Other studies (Akey et al., 2017; Kets de Vries, 1996; Petriglieri & Stein, 2012; Zaleznik, 1989) have focused on leadership and work behaviours of entrepreneurs.

Several perspectives on psychoanalytic theory, such as the works of Freud, Klein or Lacan, have been used in investigating managerial issues and so contributed to management and organization studies (Arnaud & Vidaillet, 2018; Brown et al., 2013; Dashtipour & Vidaillet, 2017; Desmond, 2013; Driver, 2017a, 2017b; Komporozos-Athanasiou & Fotaki, 2015; Moxnes, 2013; Pratt & Crosina, 2016; Vidaillet & Gamot, 2015). Furthermore, such approaches have introduced a range of psychoanalytic concepts and techniques to studies of organizations, including the existence of metaphors or their “projection” into organizational reality (e.g., Morgan, 1980), countertransference and dream analysis (de Rond & Tunçalp, 2017), or the projection and introjection process (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Gabriel, 1998).

A seminal figure here is Sigmund Freud, who showed that human beings are a complex combination of conscious and rational aspects as well as of unconscious, irrational, and infantile aspects of the self. Freud considered the unconscious to be an aspect of the human psyche composed of thoughts and desires that have been repressed and forced out of consciousness. As the product of the human unconscious, dreams are a core concept in Freudian psychoanalysis, existing as forms of “wish fulfilment”. Freud (1990) saw dreams as allowing access to parts of the mind that are inaccessible through conscious thought. Therefore, the unconscious is the place or mental territory into which painful and dangerous ideas and desires are deposited through repression and other defensive mechanisms (Elliott, 2015). Moreover, Freud (1917[1915], p. 223) considered dreams “among other things [as] a projection, an externalization of an internal process”. The mechanism of projection allows dreamers to transfer their repressed desires onto other people. Thus, through projection, people tend to attribute to external objects or subjects the repressed desires that they do not give themselves permission to experience directly. This concept of projection is related to that of introjection. The introjection mechanism is a process through which people internalize beliefs or behavioural patterns of other people, assuming specific perceptions of subjects and objects in their immediate surroundings (Freud, 1915). According to Klein (1946), the earliest and most deeply unconscious fantasies and dreams only become conscious with maturation and the development of experience through introjection and projection processes.

Introduced by Ferenczi (1909), projection and introjection mechanisms are the basis of the “transference” process, through which people redirect their repressed feelings onto others. According to Ferenczi (1952), identification through projection (externalization) and through introjection (internalization) is of fundamental importance in deepening working relationships.

The most famous student of Freud, Carl Gustav Jung, shared Ferenczi’s interest in these two parallel mechanisms as well as the concept of dreams. Projection is the expulsion of subjective content onto an object; it is the opposite of introjection. Accordingly, it is a process of dissimilation, through which subjective content becomes alienated from the subject and is, so to speak, embodied in the object (Jung, 1971). Projection is not a conscious process. The general psychological explanation for projection is an activated unconscious that seeks expression (Jung, 1977).

Like Freud, Jung believed that dreams are a way of communicating with the unconscious or, specifically, a window to the unconscious. He described dreams as: “The most common and most normal expression of the unconscious psyche” (Jung, 1974, p. 73). The unconscious is viewed as the “matrix of dreams”, with an independent function or autonomy to the conscious mind; furthermore, Jung argued, dreams are affected not only by the unconscious psyche (as argued by Freud) but also by the collective unconscious.

The collective unconscious, also known as archetypes, does not derive from personal experience and does not individually develop, but rather is common to people sharing the same culture (Jung, 1959, p. 55). Jung’s archetypes are collective, universal categories affecting human behaviour. Archetypal ideas are the conscious translation, interpretation, and pictures of archetypes in the superficial psychological layer, such as dreams, visions, myths, and symbols (Jung, 1959). Furthermore, Jung stresses the role of the introjection mechanism in showing the process through which the human psyche absorbs several dogmatic beliefs induced by the environment or the collective unconscious (Jung, 1959).

The psychoanalytic perspective, with its attendant concepts of dreams, projection, and introjection, might contribute to a better understanding of the entrepreneurial process. Running a business is not necessarily a rational process; in many cases, the process appears to be a retrospective “rationalizing” of decisions already made unconsciously by the entrepreneur (Kets de Vries, 1996). Thus, mechanisms of projection and introjection allow a deeper understanding of an entrepreneur’s unconscious.

The conceptual framework“Organizations are processes of human behaviours that are experienced as experiential and perceptual systems governed by unconscious processes” (Diamond & Allcorn, 2003, p. 492). Gabriel (1995) and Rhodes & Brown (2005) used the concept of the “unmanaged organization” to describe organizational realities driven by desires, anxieties, and emotions. The former described this as “an organizational dreamworld in which desires, anxieties, and emotions find expressions in highly irrational constructions” (Gabriel, 1995, p. 479). Therefore, these unconscious ideas, desires, and emotions significantly impact emotional obstacles that are seen in organizations, such as envy, ambition, failure, fear, and rejection.

According to Lyons-Ruth (1999) and Fonagy (2018), within organizations the communication processes between members can result in specific relational perceptions based on projections and unconscious mechanisms. Hoffman (1992) found that each individual plays a dramaturgical role in organizations, unconsciously introducing inner dreams, emotions, feelings, past experiences, and expectations. Fantasies, emotions, and unconscious desires help to understand individual behaviour, including the dreams of consumers and employees, the ambition of leaders, and the emergence of entrepreneurs in organizations (Akey et al., 2017). Thus, organizational dynamics seem to be affected by the dreams and personal histories of its members.

Entrepreneurs’ dreams unconsciously guide individual and organizational psychological dynamics through a circular process in which dreams are transformed and concretely expressed. The entrepreneurial process can be considered the projection of the conscious and unconscious dreams of entrepreneurs, through which they formulate and realize their business ideas with new venture creation. At the same time, beliefs, values, and symbols absorbed by the environment or the collective unconscious (through introjection) play a role in guiding the implementation of business ideas.

The conceptual framework illustrated in Fig. 1 portrays a set of interrelated processes that can help to explain entrepreneurial behaviour through the identification of three stages: dream, business idea, and new venture creation.

From dream to business ideaDreams may seem to be a narcissistic phenomenon because they are linked to the most narcissistic of mental states: sleep. They may appear to be entirely intrapsychic, and of intrinsic interest only for analytic treatment, but there are communicative elements within the dream itself and about the behavioural effects of the dream that are of great importance not only for the therapeutic approach. If the dream is considered a tendency within the dreamer to establish contact with reality, in line with Freud’s (1990) theoretical formulation, it is fair to say that individuals unconsciously tend to transform their nocturnal dreams into reality during daily life. Individuals can, therefore, become aware of their most authentic and deepest desires through the psychoanalysis of their dreams (Kanzer, 1955). Freud acknowledged that dreams are of great importance in understanding the interaction between the conscious and the unconscious (Hochwarter, Witt, & Kacmar, 2000).

Listeners or observers can also appreciate the unconscious aspects of dreams by analysing their effects on dreamers’ actions and day-to-day results (Kanzer, 1955). Most of the behaviours of dreamers are guided by their unconscious mind and their dreams.

Steve Jobs,1the late CEO and co-founder of Apple and Pixar Animation Studios, believed in dreaming big. This successful businessman can truly be said to have inspired others to dream bigger and think greater in every aspect of life and business. “If you are working on something exciting that you really care about, you don’t have to be pushed. The vision pulls you,” Jobs said. Though he was told over and over again that he would never achieve his dreams, his response was always “why not?” Jobs triggered the imagination of his followers to show them a world in which they dreamt of living.

Freud showed that desires are initially repressed, which later leads to projection. There are two types of unconscious repression processes, initial and later (Grünbaum, 2001). The initial repression is in response to libidinal demands (a taboo, intense wish for sexual fulfilment). Later repressions involve anxiety avoidance as a result of an earlier situation of danger. These processes lead to projection. Thus, projection results in “inserting oneself” into an object so as to form an image of the self in interaction with the object. This perceptual process is necessarily a process of matching the object with one’s “unconscious phantasies” (Klein, 1946; Malancharuvil, 2004).

Therefore, as stated by Kets de Vries (1996, p. 28), the enterprise becomes an extension of the entrepreneur and of their dreams: “a space between inner and external reality, a place where he could re-enact his fantasies”. Through the analysis of a case study, Kets de Vries (1996) showed that strategic decisions, such as the choice of industry or the selection of portfolio products, could be related to playful fantasies of childhood.

For example, having an imaginary friend or transforming toys during play as a child could affect adult choices and entrepreneurial behaviour. The life of Walter Elias Disney,2the founder of Walt Disney Co., is a significant example of how the playful fantasies of childhood can be the basis for creating a successful business venture. Disney’s childhood cannot be considered happy as it was dominated by the presence of a strict father. Drawing became an escape for young Disney from his authoritarian parent. Thus, “he created his own little fantasy world where life was always beautiful; people were always happy”. Disney dreamed of creating an amusement park based on his characters and then, in the early 1950s, he was able to finance the construction of such a park. Opened in 1955, Disneyland is one of the world’s most popular tourist attractions, becoming the real-life version of Disney’s fantasies, which he had escaped to in his youth. Disney said: “If you can dream it, you can do it”.

Therefore, through the projection of feelings, wishes or dreams are expelled from the self and located in another person or object (Malancharuvil, 2004). Furthermore, interaction with the object generates a further process of introjection through the internalization or acceptance of the perception of the stimulus (the object). In fact, according to Freud, dreams are highly symbolized visual products of perception based on everyday experience. Introjection could lead to revising the original dream in order to adapt it to the environment.

Federico Marchetti had a youthful dream to work at Disney in the cartoons department,3but he did not succeed. His career took a different direction: Marchetti is the founder of the world’s largest online luxury fashion retailer, Yoox Net-a-Porter. However, he never forgot his youthful dream, and today he succeeded in realizing it. Marchetti secured an exclusive partnership between Disney and Yoox that meant merchandise such as stormtrooper dolls, moonboots, or Markus Lupfer’s Bambi sweatshirts will only be available through Yoox.

Jung (1959, p. 59) stated that “dreams often contain fantasies which ‘want’ to become conscious”. Therefore, regarding the relationships between entrepreneurs’ dreams and business ideas, we suggest the following proposition:Proposition 1 The projection of the entrepreneur’s dream affects the definition of the business idea, which, in turn, through an introjection process, changes the entrepreneur’s original dream, supporting its transformation in time.

According to Freud, deep psychological processes and irrational forces, in particular, affect behaviour and thus organizational actions. Therefore, the business idea definition and realization are not necessarily a rational process but rather a process of projection of the “dark” or unconscious side of entrepreneurs, through which they convert their dreams into new venture creation.

Techno-rationalist logics are weakened and outdated by latent psychosocial dynamics. Entrepreneurs’ goals of self-realization are affected by deep, strong, and personal dreams rather than economic scenarios and the workplace (Allcorn, 1996; Kets de Vries, 1994). Unconscious organizational dynamics shape what happens in the workplace more than visible components such as policies and procedures, services and products, hierarchies, tasks and offices (Jaques, 1995), debunking the conscious and rational organizational structures (Diamond & Allcorn, 2003).

The way in which these intrapsychic themes are translated into external reality can affect performance and determine the success or failure of the enterprise. Organizational performance may be improved by entrepreneurs through growing processes of awareness of their own psychological realities and subjectivities of the workplace. Through focusing on transference and countertransference dynamics among themselves, groups and organizational members as powerful sources of meaning and direction, entrepreneurs can redefine and find their right place within the organization (Antonacopoulou & Gabriel, 2001; Baum, 1994; Levinson, Molinari, & Spohn, 1972; Stein, 1994).

For example, the company designed by Adriano Olivetti was strongly influenced by his philosophical view of entrepreneurship, personal ethics,4and political perspective. He dreamed of a company that put people and communities at the centre of the business. In 1932, Olivetti succeeded in realizing his dream by projecting his values onto his father’s typewriter business. His vision for the company was focused on treating workers fairly and in investing in their wellbeing. Aside from the higher salaries, several social services were provided to employees while culture and art infused the workplace. In addition to focusing on workers’ conditions, Olivetti believed that the company should play a central role in the local community as well as in the social and political structure. Thus, his company maintained a strong link to the city of Ivrea, where it was founded. Olivetti said: “Often the term utopia is the easiest way to sell off what one doesn’t have the will, capacity or courage to do. A dream seems a dream until you begin to work on it. Then it can become something infinitely bigger”.

Thus, Olivetti’s enterprise became a “symbolic extension” of the entrepreneur and his dreams (Kets de Vries, 1996, p. 28) through a projection process. “Organizational symbolism” is an orientation within organization theory that interprets social life in organizations under the assumption that symbols and meanings are essential aspects of human affairs and that these form the basis for collective action and social order (Alvesson, 1991). Dandridge, Mitroff, and Joyce (1980, p. 77) defined organizational symbolism as “those aspects of an organization that its members use to reveal or make comprehendible the unconscious feelings, images, and values that are inherent in that organization”. It involves the construction of meaning in organizations, providing a basic perspective that views all organizational phenomena as being symbolic. Within organizations, symbolism is highlighted by ideology, character, and a value system. Stories, logos, jokes, celebrations, and particular verbal expressions are just some expressions of organizational symbolism that may become the targets of close phenomenological investigations over time (Dandridge et al., 1980; Pondy, Frost, Morgan, & Dandridge, 1983).

Brunello Cucinelli is a cashmere entrepreneur and CEO and founder of Brunello Cucinelli S.P.A.,5which operates in the luxury fashion sector. His company offers high-quality prêt-à-porter garments of excellent quality and typical “Made in Italy” craftsmanship. In 1978 Cucinelli established his company driven by the desire to create a different way of doing business in the 21st century: “My dream of a lifetime has always been to make human work more human, arguing that work enhances human dignity. During my lifetime, I have always nurtured a dream: useful work to achieve an important goal. I have always felt that business profit alone was not enough to fulfil my dream and a higher purpose was to be found”. His philosophy of a different way of conceiving of business and workers was defined as “humanistic capitalism”: “no profit comes before taking care of mankind”. The choice of the company’s site represents this philosophy: Solomeo in Umbria is a typical medieval village in the centre of Italy, traditionally focused on the production of olive oil and wine, and from 1978, the creation of cashmere. The Solomeo site symbolized Cucinelli’s ability to find a fit between corporate goals and human needs, the possibility of merging profit and values and business actions and human relations development, preservation of the past and innovation, and working in harmony with the local context in a global dimension.

Gabriel and Carr (2002) highlighted that working within an organization can encourage some individuals to introject collective categories, whereby they characterize their context and feel a strong identification with organizational ideals based on specific behaviours, values and symbols. Therefore, within firms, Jungian archetypes could be considered a form of symbolism highlighted by ideology, culture or a values system that unconsciously affects the behavioural actions of its members.

The environment or change market provides continuous input that generates responses from the entrepreneur, but these responses depend on the ways in which the entrepreneur perceives them. By internalizing these changes through an introjection process, the entrepreneur can decide to modify the business and organization of the new venture. Furthermore, such process can stimulate further different forms of external action through projection.

The Impossible Project is a photography and manufacturing company founded in 2008 by Dr Florian Kaps (a former manager of the Lomographic Society) and André Bosman (a former employee of the Polaroid company) after Polaroid announced that it would stop producing instant film for its cameras.6The main aim of the founders was to reinvent instant film materials for use in existing Polaroid cameras. In 2008, The Impossible Project bought Polaroid’s production machinery and leased its production plant in Enschede, the Netherlands. In 2010, the company started the mass production and sales of new instant film for some existing Polaroid cameras. Apart from the instant film, the Impossible Project teamed up with Polaroid to launch a range of collectable products, called The Polaroid Classic line, and it also introduced its own new range of Impossible cameras. Today, Impossible is no longer a project but a fast-growing company with more than 130 employees and many offices in major cities worldwide. Nine years after its founding, as noted on the Impossible Project website, it seemed that the company had “reinvent[ed] analogic instant photography in a digital world”. In May 2017, Polaroid’s brand and related intellectual property were acquired by the largest shareholder of the Impossible Project.

Consequently, the relationships between the formulation and realization of a business idea through new venture creation can be explained with the following proposition:Proposition 2 Entrepreneurs transform their business ideas into new ventures through a projection/introjection process.

The manuscript aims to contribute to the existing scholarship on the behaviour of entrepreneurs engaging in the process of creating new ventures. Building upon the literature on the entrepreneurial process of new venture creation and psychoanalytic theory, the research developed a conceptual framework to explain the entrepreneurial process of new venture creation. This consists of three different stages: dream, business idea, and new venture creation. The proposed framework provides a more profound understanding of the actions of the entrepreneur and offers new insights into the evolution of the entrepreneurial process.

By building upon the dream concept and psychoanalytic mechanisms of projection and introjection, the study states that the entrepreneurial process can be the projection of the conscious and unconscious dreams of entrepreneurs, through which they formulate and realize their business ideas with new venture creation. It further believes that running a business is not necessarily a rational process, but rather the output of a process influenced by the unconscious, desires, dreams, and fantasies. The psychoanalytic perspective provides a more profound understanding of the motives and actions of individuals and of organizational functioning by taking into account the effects of the unconscious. Fantasies and desires can help to explain individuals’ behaviour, including the dreams of consumers and employees, the ambition of leaders, and the emergence of entrepreneurs in the organization.

Furthermore, the research also suggests that the psychoanalysis of individuals’ unconscious representations, such as deeper fantasies, wishes and desires, allow us to understand behaviours including the dreams and ambitions of entrepreneurs in the organizations. Drawing attention to psychoanalysis, as a critical theory with relevant explanatory powers of the entrepreneurial process, could have the potential for thinking about organizational practice in new ways. It might illuminate individual entrepreneurial strengths and dysfunctions in terms of unconscious drivers and dreams and their alignment with the realized business. School and MBA courses encourage most entrepreneurs to match ideal standards of excellence, which may result in a dramatic gap between authentic unconscious traits and desires and apparent successful image as businessperson.

Source: Steve Jobs’ Commencement Address at Stanford University (June 12, 2005) http://news.stanford.edu/news/2005/june15/jobs-061505.html

Source: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/197528https://www.virgin.com/entrepreneur/the-philosophy-of-epic-entrepreneurs-walt-disney

Source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2017/02/11/will-become-ferrari-federico-marchetti-yoox-net-a-porter-ambitions/

Source: https://qz.com/455328/this-italian-company-pioneered-innovative-startup-company-in-the-1930s/