People with schizophrenia have neurocognitive as well as social cognition deficits. Numerous studies have shown impairment in these domains in patients with chronic schizophrenia. However, these disturbances during the early phase of the disease have been less studied.

ObjectiveThe aim of the study is to explore the theory of mind (ToM) and emotional processing in first-episode patients, compared to healthy subjects.

MethodForty patients with a first psychotic episode of less than 5 years’ duration, and 40 healthy control subjects matched by age and years of schooling were assessed. The measures of social cognition included four stories of false belief, the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET) and the Pictures Of Facial Affect (POFA) series.

ResultsThe patients with a first psychotic episode performed significantly worse in all tasks of social cognition, compared to the healthy controls. The second-order ToM was impaired whereas the first-order ToM was preserved in the patients. Happiness was the emotion most easily identified by both patients and controls. Fear was most difficult for the patients, while for the controls it was disgust.

ConclusionsDeficits in ToM and emotional processing are present in patients with a first psychotic episode.

The term social cognition refers to the set of mental operations that underlie social interactions and that include perceiving, interpreting and generating responses to the intentions, dispositions and behaviours of others.1

Numerous studies have found that social cognition is impaired in schizophrenia.2 In this regard, in 2012 Green et al.1 verified the presence of alterations in social cognition throughout the illness. Along the same lines, in 2014 Vohs et al.,3 describe alterations in social cognition in schizophrenia, in comparison with other psychiatric illnesses.

Some authors point out that alterations in social cognition could explain the origin of some clinical symptoms.4,5 On the other hand, social cognition acts as a mediating variable between neurocognition and real-world functioning, being associated with the patient's functional response,6 and highly predictive of it.7,8 In schizophrenia, the presence of impairments in social cognition is associated with impaired functioning in activities of daily living and performance at work or school, as well as in social functioning.9–11

Theory of mind (ToM) is a key function of social cognition.12 It refers to the ability to infer mental states such as desires, intentions, dispositions and beliefs about oneself and others in order to explain and predict behaviour.13–15 It is a multidimensional construct that includes the understanding of false beliefs, advice, intentions, deceptions, metaphors and ironies,16 and depending on the level of difficulty we can speak of first- or second-order ToM. A difference is also made between affective and cognitive ToM. While cognitive ToM is identified with knowledge of beliefs, affective ToM refers to knowledge about emotions. Both seem to be affected in schizophrenia.17

Deficits in mentalisation have been repeatedly observed in people with schizophrenia.4,18–20 Furthermore, most studies support the idea that this impairment can be considered as a deficit-trait, supporting the existence of a potential endophenotype for schizophrenia.16,21,22 Some recent studies suggest that these deficits are also present in the early stages of schizophrenia,23–27 even after controlling for the effect of intellectual level.3,28

Finally, emotional processing refers to the perception and use of emotions.29 This includes the identification of emotions expressed through facial expression, as well as tone of voice, in addition to emotional management, regulation or facilitation.30

Edwards et al.,31 in 2001, and Hellewell and Whittaker,32 in 1998 observed that individuals with schizophrenia show deficits in emotional perception. In the case of facial emotional processing, individuals with schizophrenia, in general, show impairment in facial affect recognition,31,33 both in the identification and discrimination of emotions.34,35 Other authors point out that deficits are greater in the identification of negative emotions, compared to positive emotions, with happiness being the easiest emotion and fear the most difficult to identify, both in patients and in healthy individuals.36,37

Impairment in emotional perception also appears in the early stages of the disease.27,38 Edwards et al.31 report that groups of subjects with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, compared to controls, perform more poorly in facial affect recognition. In addition, groups of subjects with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders have lower mean scores in the categories of fear and sadness in facial affect identification compared to healthy people.

The relationship between IQ in patients with first-episode schizophrenia and scores on tests of social cognition remains unclear. While some authors such as Bertrand et al.39 claimed that differences in ToM were not modified when IQ was taken into account, other authors, such as Bliksted et al.28 pointed out that tasks requiring complex cognitive commands do seem to be related to IQ.

Given all these results, we can state that numerous studies have comprehensively analysed social cognition in the chronic phase of schizophrenia; however, fewer studies have been carried out in the early stages of the illness.40 Given the importance of social cognition for functional recovery in schizophrenia, we consider it necessary to examine social cognition soon after a first psychotic episode. Therefore, the aim of the present work is to analyse social cognition in people with a first psychotic episode. Specifically, two domains of social cognition will be studied: cognitive and affective cognition and emotional processing. It is hypothesised that compared to the control group, the first psychotic episode group will present deficits in social cognition showing a greater deterioration in the domains under study.

MethodParticipantsThe sample consisted of 80 participants. Forty patients (20 males and 20 females) between the ages of 18 and 45 with a first psychotic episode and an evolution of the illness of less than 5 years were recruited at the Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí in Sabadell (Catalonia, Spain) to participate in the study. The patients met the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.41,42 The diagnosis was obtained from each patient's medical records and confirmed by administration of the Clinical Version of the DSM-IV Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I Disorders (SCID-I-VC).43 Inclusion criteria were: (1) being an outpatient patient for at least 4 weeks prior to the study (clinical stability); (2) no change in antipsychotic medication during the month prior to the study; (3) a score below 4 on items P1, P2 and P3 of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)44; (4) a score of less than 4 on the Calgary Depression Scale (CDSS)45; (5) no history of substance abuse (except for nicotine or caffeine) in the past year; (6) an IQ greater than 70; and (7) no history of brain damage or severe sensory impairment. Patients with any type of psychiatric comorbidity were not included in the study.

Forty healthy controls (20 males and 20 females) were selected and matched to the sample of subjects with a first psychotic episode, age, sex and years of schooling. The inclusion criteria were the same as for the patients, except for criteria 1, 2 and 3.

All participants were previously informed of the characteristics and procedure of the study and of the voluntary nature of their participation and signed an informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Parc Tauli.

ToolsClinical and psychopathological measurementsA clinical assessment was performed on all patients using the Spanish version of the PANSS46 and the CDSS.47

In the control group, to exclude the presence of psychiatric disorders, the Spanish version of the International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0.0 (MINI)48 was administered.

Neuropsychological measuresThe intellectual capacity of the patients was estimated using the abbreviated form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III (WAIS-III).49 In the control group, IQ was estimated from the vocabulary subtest of the WAIS-III.50

Measures of social cognitionCognitive ToM was assessed by means of false belief tasks. This consisted of the telling of four short verbal stories. The Sally &Anne51,52 and Thecigarettes53 stories assess first-order false belief comprehension, while The ice-creamvan52 and Theburglar53 stories assess second-order false belief comprehension. In all stories, for each question the subject scores 0 (incorrect) or 1 (correct). Both the first- and second-order stories have, respectively, good levels of internal consistency (α=.51 to .62 and α=.84), and an adequate Pearson test–retest correlation (.77 and .66).54

Affective ToM was measured with the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET).55,56 In this test, the subject has to know and understand terms related to complex mental states (arrogant, assertive, hostile, …) and try to relate them to the expression transmitted through the gaze. The test consists of 36 black and white photographs of human faces, male and female, in which only the eye region is shown. Along with each photograph, four words referring to thoughts and feelings are written. The internal consistency of the test is α=.810.57

For the assessment of emotional processing, the Pictures Of Facial Affect (POFA)58 was administered. Specifically, the Ekman 60faces59 was used. This instrument consists of the presentation of 60 POFA photographs showing randomly faces of people with different facial expressions: sadness, anger, joy, disgust, surprise and fear. The subject must match each photograph with one of four possible basic emotions. For the internal consistency value (α=.704) – see Young et al.59

ProcedureA psychiatrist reviewed each new patient for compliance with the inclusion criteria, reported the study and collected informed consent. Patients were included in the study consecutively. Social and demographic data were collected for each participant and the SCID-I-VC, the PANSS and the CDSS were administered. A psychologist administered the short form of the WAIS-III Intelligence Scale, the MINI and the vocabulary subtest of the WAIS-III, and subsequently administered the theory of mind (false belief stories and RMET) and emotional processing (POFA) tasks.

Statistical analysisComparison of groups (patients and controls) on socio-demographic and clinical variables was performed using Chi-square and Student's t-tests. For measures of social cognition the Chi-square test was used in addition to the non-parametric Mann–Withney U test. Normality of the data was explored using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Significance was established at p value <.05. All analyses were performed with the statistical package SPSS v.19.

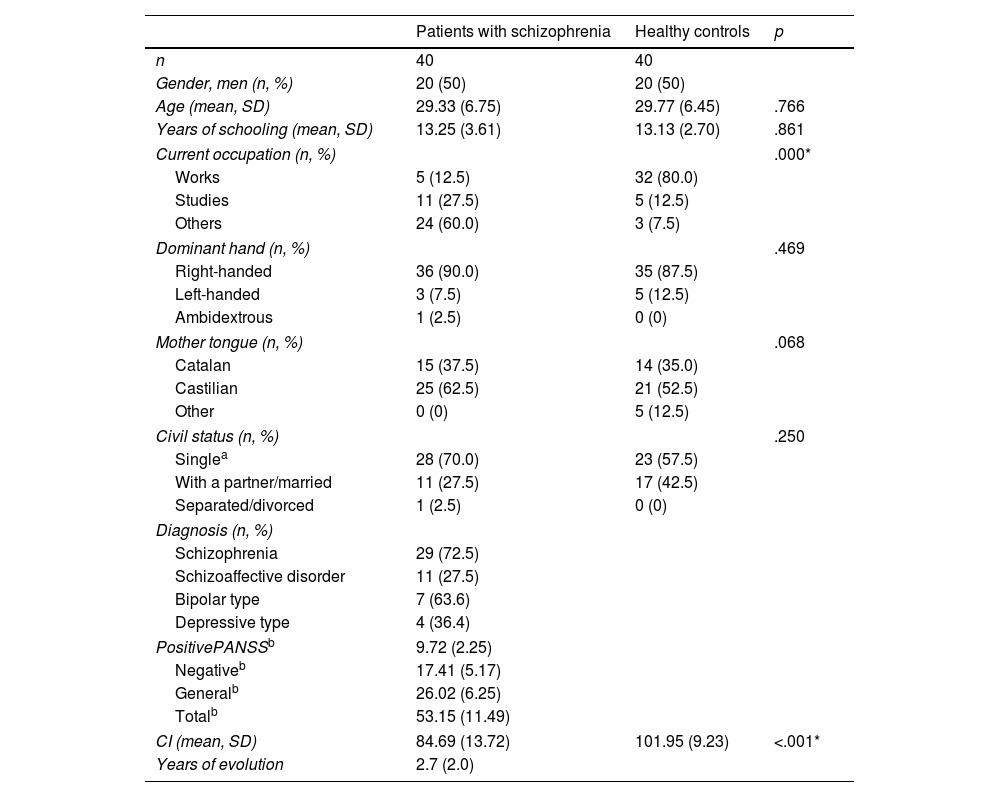

ResultsThe description of the study sample and the clinical and neuropsychological measures are contained in Table 1.

Socio-demographic data and clinical and neuropsychological measurements.

| Patients with schizophrenia | Healthy controls | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 40 | 40 | |

| Gender, men (n, %) | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 29.33 (6.75) | 29.77 (6.45) | .766 |

| Years of schooling (mean, SD) | 13.25 (3.61) | 13.13 (2.70) | .861 |

| Current occupation (n, %) | .000* | ||

| Works | 5 (12.5) | 32 (80.0) | |

| Studies | 11 (27.5) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Others | 24 (60.0) | 3 (7.5) | |

| Dominant hand (n, %) | .469 | ||

| Right-handed | 36 (90.0) | 35 (87.5) | |

| Left-handed | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Ambidextrous | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Mother tongue (n, %) | .068 | ||

| Catalan | 15 (37.5) | 14 (35.0) | |

| Castilian | 25 (62.5) | 21 (52.5) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Civil status (n, %) | .250 | ||

| Singlea | 28 (70.0) | 23 (57.5) | |

| With a partner/married | 11 (27.5) | 17 (42.5) | |

| Separated/divorced | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | |||

| Schizophrenia | 29 (72.5) | ||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 11 (27.5) | ||

| Bipolar type | 7 (63.6) | ||

| Depressive type | 4 (36.4) | ||

| PositivePANSSb | 9.72 (2.25) | ||

| Negativeb | 17.41 (5.17) | ||

| Generalb | 26.02 (6.25) | ||

| Totalb | 53.15 (11.49) | ||

| CI (mean, SD) | 84.69 (13.72) | 101.95 (9.23) | <.001* |

| Years of evolution | 2.7 (2.0) | ||

IQ: Intelligence Quotient; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SD: standard deviation.

Significant differences were only observed in relation to current occupation, as the group of people with schizophrenia had a significantly lower rate of occupationally active subjects compared to the control group.

IQ was found to differ significantly between the two groups – t(68)=−6.600, p<.001 – with the patients having a significantly lower IQ compared to the control group.

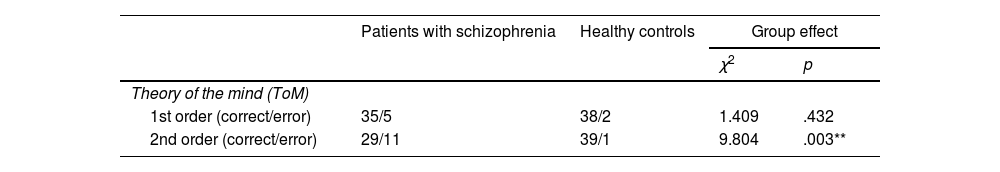

Table 2 shows the results of the social cognition tests obtained by each group.

Comparison of performance in social cognition.

| Patients with schizophrenia | Healthy controls | Group effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | |||

| Theory of the mind (ToM) | ||||

| 1st order (correct/error) | 35/5 | 38/2 | 1.409 | .432 |

| 2nd order (correct/error) | 29/11 | 39/1 | 9.804 | .003** |

| U | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective ToMRMET (mean, SD) | 22.35 (4.18) | 28.95 (3.22) | 164.50 | <.001*** |

| Emotional processing (mean, SD) | ||||

| Total POFA | 44.45 (6.43) | 52.45 (3.62) | 207.00 | 0.000*** |

| Sadness | 7.30 (1.94) | 8.50 (1.15) | 468.00 | .001*** |

| Disgust | 6.97 (1.69) | 7.72 (1.57) | 595.50 | .046* |

| Anger | 6.57 (1.93) | 9.05 (.99) | 212.00 | <.001*** |

| Surprise | 8.32 (1.47) | 9.28 (.88) | 484.00 | .001*** |

| Fear | 5.77 (2.22) | 7.93 (1.72) | 364.50 | <.001*** |

| Joy | 9.50 (1.01) | 9.98 (.16) | 617.00 | .003** |

POFA: Pictures Of Facial Affect; RMET: Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; SD: standard deviation; ToM: theory of the mind.

aChi-square test.

bMann–Withney U test.

No significant differences were observed in the first-order ToM histories between the patient group and the control group. However, significant differences were found in the second-order ToM histories between the patient group and the group of healthy subjects.

Significant differences between the study groups were also observed in the RMET test (p<.001).

In terms of emotional processing, both the overall POFA performance (p<.001) and the performance on each of the emotions assessed (happiness p=.003; sadness p=.001; disgust p=.046; anger p<.001; surprise p=.001 and fear p<.001) differed significantly between patients and controls, with the patient group performing worse.

DiscussionThis study examined social cognition in a group of patients with a first psychotic episode in comparison with a group of healthy subjects.

The results confirmed our hypotheses by showing significant differences between patients and healthy subjects on measurements of social cognition. Patients with a first psychotic episode show impairment in ToM and emotional processing tasks. Several studies have shown similar results in patients in early stages of the illness.2,3,23,26–28 Patients with a first psychotic episode have difficulty in recognising and inferring the beliefs of others. Even in the earliest phases of the illness, they show a specific impairment in second-order mentalisation, similar to that observed in chronic patients. Similar to the results obtained by Achim et al.23 and Inoue et al.,24 our first-episode patients show difficulty in inferring people's thoughts in social interaction situations, as well as in differentiating them from their own mental state. However, along the same lines, but contrary to data from some previously published studies,20,60 we did not observe an alteration in first-order mentalisation. These results with respect to cognitive ToM can be understood if we take into account that second-order mentalisation is a form of ToM that requires a higher cognitive demand. The cognitive capacities involved in second-order ToM are more sophisticated than those involved in first-orderToM.61 Thus, in early stages of the disease, there may be poor performance in those aspects of mentalisation that require high cognitive effort, and yet first-order ToM may be preserved, since the cognitive functions it requires are still preserved. And it is with the progression of schizophrenia that a general deterioration of cognitive abilities occurs, which will result in the impairment of both first- and second-order cognitive ToM in chronic patients.

In our patients we observed a deficit in affective ToM. Along the same lines as Vohs et al.,3 the group of patients has greater difficulty than the group of healthy subjects in detecting emotions and/or feelings (arrogant, assertive, hostile, …) through gaze.3 The deterioration of the affective ToM in first-episode patients could be a consequence of the alteration of other cognitive functions and processes, such as emotional processing, which are simpler but essential.

Our first-episode patients not only showed difficulties in attributing the mental states of others, but also in other domains of social cognition such as emotional processing. Difficulty in recognising emotions through facial expression was observed, with a significant deficit in the identification of basic emotions. This difficulty is consistent with the results obtained previously by studies suggesting the presence of a deficit in facial recognition of emotions in first psychotic episodes, in comparison with healthy subjects.3,31,34,62 Moreover, these deficits found in subjects in the early stages of the illness are similar to those reported by other authors in patients in the chronic phase.31–33,63

Patients with a first psychotic episode have significantly worse facial identification of all basic emotions (joy, sadness, disgust, anger, surprise and fear), with worse performance in detecting sadness, anger, surprise and fear. In line with Marwick and Hall36 and Healey et al.,37 we found that in patients the emotion of joy is the easiest emotion to identify, while fear is the most difficult emotion to identify. In the case of young people, also in the same direction as Marwick and Hall,36 joy remains the easiest emotion to identify. However, in our study, it is not fear that is the most difficult emotion, but rather disgust. Our results are also out of sync with those of Sachs et al.,62 since the elderly find it more difficult to identify sadness than their male counterparts.

These differences between the results of different studies may indicate that the deficits in facial identification of emotions may not be specific to emotional valence. However, the explanation for this difference in valence should take into account the use of different tests for the assessment of emotional processing in each study.

Since the processing of emotions is based on a chain of mental operations related to a complex set of cognitive skills, we can assume that deficits in facial emotional processing could be related to the impairment of certain cognitive functions. Indeed, functions such as attention, memory, or the capacity for abstraction, which are impaired in schizophrenia, may explain the poor performance of these subjects.1,61,62

Likewise, this misinterpretation of facial affect in patients with a first psychotic episode could lead to social isolation, followed by repeated dysfunctional social interactions provoked by the same deficit.10,25,29

We can therefore affirm that deficits in social cognition in patients with a first psychotic episode extend beyond the specific impairment of ToM, which can be considered as the key domain of social cognition, with emotional processing also being affected. All this is evidence of the presence of general deficits in the field of social cognition and, consequently, of the complexity of this construct in schizophrenia.

This paper has used tests of social cognition whose ecological validity may be debatable. On the other hand, some tests have now been developed that have a more naturalistic character, such as the Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition instrument (MASC), designed by Dziobek et al.64 and Versailles-Situational Intention Reading (V-SIR) by Bazin et al.65. However, some studies have shown a strong correlation between measurements made with these instruments and those used in this paper. Thus, Lahera et al.66 demonstrated a strong correlation between the MASC-SP and the OPFA and the RMET. On the other hand, Catalan et al.67 found similar deficits to those obtained in our study, using the MASC.

To sum up, our results suggest that deficits in social cognition, specifically in the ability to infer mental state and to perceive and interpret the emotions expressed by others, begin early in the course of the disease. This fact, together with the data reported by earlier studies that refer to these same deficits at later stages of the illness, supports the view of deficits in ToM and emotional processing as features of schizophrenia. However, longitudinal studies and more data are needed to corroborate this idea.

Deficits in social cognition have an impact on functional response making social interaction in schizophrenia difficult. Their early identification is therefore necessary for the subsequent design and implementation of specific intervention programmes. These programmes should be aimed at training and improving social cognition skills in the early stages of the illness, thus reducing its impact on the subject's life and promoting a greater functional response.

This study has some limitations that need to be considered. Firstly, the group sizes are relatively small, reducing the ability to extrapolate the results to the target population.

Although we controlled for the fact that there were no changes in medication during the month prior to the assessment, we cannot know what possible effect antipsychotic medication had on performance on social cognition tasks in the patient group, considering that the use of antipsychotic medication is related to social functioning in schizophrenia.68

Furthermore, the IQ variable was not considered as a variable in the statistical analysis when studying the differences in social cognition between the first-episode group and the control group. This could have had an effect on the performance of both groups.

Finally, in this study social cognition was not assessed in its entirety, since only two domains were considered, and it should also be taken into account that no Spanish or Catalan scores were available for some of the tests used.

ConclusionCompared to healthy control subjects matched for age, sex and years of schooling, patients with a first psychotic episode and less than 5 years of evolution show significant deficits in several aspects of social cognition, including ToM and emotional processing. Thus, already in the early stages of the illness, difficulties are observed in the ability to attribute mental states of others and to recognise emotions through facial expression, resulting in difficulties in social interaction.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

This study (091331) was funded by “La Marató” from TV3.