Dissociative symptoms are a type of phenomenon which is present in a wide variety of psychopathological disorders. It is therefore necessary to develop scales that measure this type of experience for therapy and research. Starting out from the bipartite model of dissociation, this study intended to adapt and validate the Detachment and Compartmentalization Inventory (DCI) in Spanish.

Material and methodsFor this, 308 participants (268 from the community population and 40 with psychiatric pathology) completed the DCI, the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-II), the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ20) and the Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS).

ResultsThe results showed that the Spanish version has a two-factor structure similar to the original version and was invariant across participants. The reliability of DCI scores was adequate and acquired evidence of validity related to other instruments.

ConclusionsIt is concluded that the DCI is a valid scale for detecting detachment and compartmentalization dissociative experiences, both in the clinic and research.

Dissociation is considered a breakdown or lack of continuity between psychological processes that are normally integrated, such as consciousness, memory, identity, perception and motor control.1 Other authors, such as Putnam,2 have also defined dissociation as a process which produces an alteration in an individual's thoughts, feelings or actions such that during a period of time, certain information is not associated or integrated with other information, causing a series of phenomena such as alteration of memory or identity.

Dissociative disorders are included in the major diagnostic classifications (DSM-5 and ICD-11), providing better agreement with each other in their organization than in previous editions. For example, the ICD-113 includes Depersonalization-derealization disorder in this chapter of dissociative disorders. Dissociative fugue is also framed as a specification of Dissociative amnesia. These changes were not in the previous version of the ICD. However, some differences between the two classifications should also be highlighted. The ICD-11 includes conversion disorder in this chapter (as Dissociative neurological symptom disorder) and not within the Somatic symptoms and related disorders, as does the DSM-5.4 Other differences refer to the classification Trance disorder, Possession trance disorder, and Partial dissociative identity disorder, which in the DSM-5 are framed in a residual category (Other specified dissociative disorders). All of these differences show the lack of consensus in definition and classification of this type of phenomenon.

Maaranen et al.5 found that the prevalence of pathological dissociation in the community population was 3.4%. In a recent review by Brand et al.,6 the rate of dissociative disorders in hospitalized psychiatric patients varied from 1% to 20.7% and from 12% to 29% in the outpatient context. Ross et al.7 found a lifelong prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric patients of 44.5%.

There are presently two main models which attempt to explain its etiology. The first postulates that dissociation is a product derived from traumatic experiences (traumatogenic model, e.g., Bailey and Brand8). It is based on studies which have found that this type of adverse childhood experience, such as sexual or physical abuse, is associated with the appearance of dissociative symptoms in adulthood. The second model (sociocognitive or fantasy model) proposes that dissociative disorders are the consequence of social learning and of expectations, more specifically, hypothesizing that factors, such as inadvertent signals or cuing from the therapist, influence of communication media and sociocultural expectations would explain the symptomatology associated with dissociative identity disorder (DID9). However, recent reviews in which the predictive validity of these two models is compared have found that there is less scientific evidence for the sociocultural model,8 although this debate is not closed.10

Dissociation has traditionally been conceptualized as a phenomenon on a continuum.11 Thus, there would be a structural dimension from occasional and normal experiences, for example, states of absorption and daydreaming, to severe psychiatric disorders such as DID. However, this continuum hypothesis has been questioned by some authors. Cardeña12 identified three dissociation categories, and later, authors such as Brown13 and Holmes et al.14 proposed a bipartite model of dissociative disorders. This theoretical framework proposes two main categories for classifying dissociation, detachment and compartmentalization. Detachment refers to an altered state of consciousness in which there is a sensation of separation of the self or from surroundings. This category includes absorption, some types of depersonalization, derealization, affective flattening and out-of-body experiences. On the other hand, compartmentalization is related more to a deficit in control of processes or actions that normally are under one's control, including the inability to recall information that would normally be remembered. Dissociative amnesia, conversion and somatoform symptoms and DID would be placed here.14

To date, a wide variety of scales and instruments have been developed to measure dissociative experiences. All of them focus on evaluating psychological or somatic aspects of this construct, such as, e.g., the Dissociative Experience Scale (DES15), the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire-2016 and Fisher's Dissociative Ability Scale17 or specific symptoms, such as the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale (CDS18). However, until recently, no instrument has been developed that evaluates dissociation from the viewpoint of the bipartite model. Mazzoti et al.,19 based on a confirmatory factor analysis, found a three-factor structure of the DES-II,20 two of which would correspond to the two types of dissociative symptoms proposed by the bipartite model. Recently, Butler et al.21 developed the DCI (Detachment and Compartmentalization Inventory), which is a specific scale for measuring dissociation based on the bipartite model. The English version of this scale shows good psychometric properties, that is, it has good internal consistency, and evidence of convergent, discriminant and concurrent validity. Furthermore, the exploratory factor analysis showed a two-factor solution, which clearly corresponded to the detachment and compartmentalization subscales.

The distinction between the two types of dissociative phenomena is very important to research, knowledge of the etiology of the dissociative phenomena and its treatment. It is therefore necessary to develop psychometric instruments that capture both types of dissociation. This is why this article presents the Spanish adaptation of the DCI scale and the study of its psychometric properties. The specific objectives of the study were:

- •

Validate the DCI in a clinical and nonclinical Spanish population.

- •

Confirm the internal structure of the two factors in the original version by Butler et al.21

- •

Analyze measurement invariance across participants (clinical and nonclinical population).

- •

Estimate the reliability of the DCI scores and find evidence of a validity-based relationship with other variables.

- •

Find a cutoff point for the DCI subscales that discriminates between a population with and without psychiatric pathology, and the scale's sensitivity and specificity.

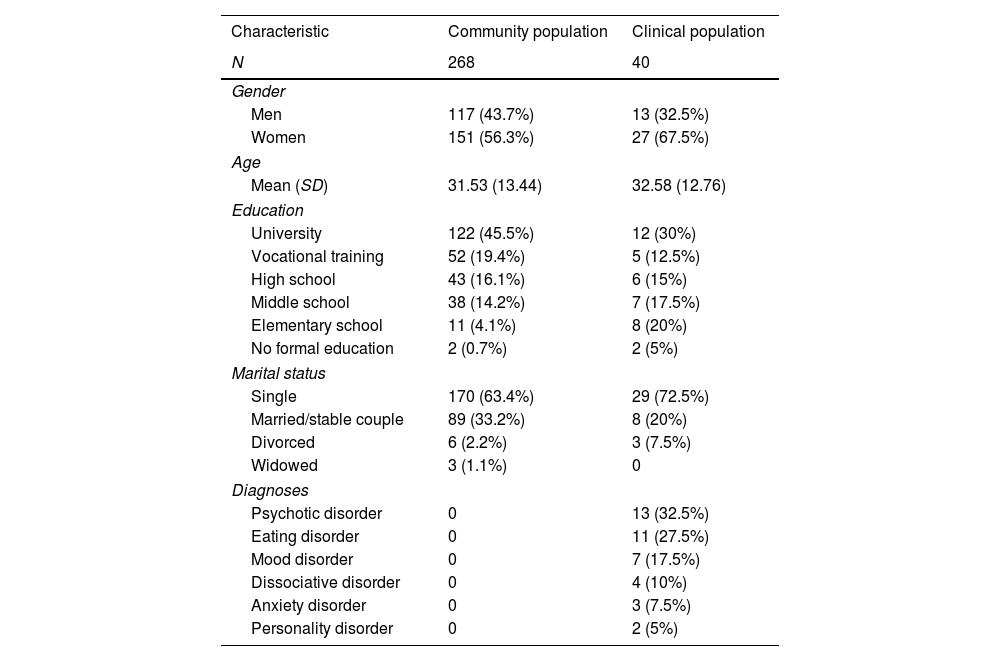

The study sample was made up of 394 participants of whom 337 were from the community population and 57 were from a clinical population. The community population was comprised of university students and non-university participants recruited by snowball sampling. The clinical group was made up of patients under treatment by the mental health services of the Virgen del Rocio Hospital in Seville (Spain) by clinical referral. The diagnoses were made following ICD-10 criteria.22 In both groups, the inclusion criterion was that they must be over 18 years of age, and in the clinical group, they had to be under treatment in the public mental health services for a psychiatric disorder. Any participant who did not meet the DCI scale validity criteria, that is have a score of 0 on Items 8 and 15 (86 participants, 69 (20.4%) from the general population and 17 (29.8%) from the clinical population) was excluded. The final sample consisted of 308 participants: 268 were from the community population, with a mean age of 31.53 (SD=13.44), of whom 117 were men (43.7%) and 151 were women (56.3%), and the 40 participants in the clinical group had a mean age of 32.58 (SD=12.76), of whom 13 were men (32.5%) and 27 were women (67.5%). No differences in age (t(306)=.46, p=.65) or sex (χ2(1)=1.78, p=.18) were found between the general and clinical population groups.

Participants excluded from the general population differed significantly from those who were not in age (t(335)=4.12, p<.05), but not sex (χ2(1)=3.14, p>.05). In particular, the participants in the group excluded were significantly older than those who were not excluded from the study (39.19 and 31.53 years old, respectively). No significant age (t(54)=1.68, p>0.05) or sex (χ2(1)=2.28, p>0.05) differences were found in the clinical group between those excluded and those who were not. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the study sample.

Participant demographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | Community population | Clinical population |

|---|---|---|

| N | 268 | 40 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 117 (43.7%) | 13 (32.5%) |

| Women | 151 (56.3%) | 27 (67.5%) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 31.53 (13.44) | 32.58 (12.76) |

| Education | ||

| University | 122 (45.5%) | 12 (30%) |

| Vocational training | 52 (19.4%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| High school | 43 (16.1%) | 6 (15%) |

| Middle school | 38 (14.2%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| Elementary school | 11 (4.1%) | 8 (20%) |

| No formal education | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (5%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 170 (63.4%) | 29 (72.5%) |

| Married/stable couple | 89 (33.2%) | 8 (20%) |

| Divorced | 6 (2.2%) | 3 (7.5%) |

| Widowed | 3 (1.1%) | 0 |

| Diagnoses | ||

| Psychotic disorder | 0 | 13 (32.5%) |

| Eating disorder | 0 | 11 (27.5%) |

| Mood disorder | 0 | 7 (17.5%) |

| Dissociative disorder | 0 | 4 (10%) |

| Anxiety disorder | 0 | 3 (7.5%) |

| Personality disorder | 0 | 2 (5%) |

This is a self-report inventory with 22 items, designed to specifically measure dissociative detachment experiences (10 items, for example, “What I see looks ‘flat’ or ‘lifeless’, as if I am looking at a picture”) and compartmentalization (10 items, for example, “I do not feel in control of what my body does as if there is someone or something inside me directing my actions”) when not under the effects of alcohol or drugs. Furthermore, it also has two items for measuring the validity of the responses (for example, “I cross the street where there is no pedestrian crossing or crosswalk, i.e., jaywalk”). Each of the items is answered on an eight-point Likert-type scale which measures the frequency of these experiences (0: never, 7: daily). In the original study by Butler et al.,21 the Cronbach's alpha for the total scale score was .97, for the detachment subscale .93, and for the compartmentalization subscale it was .96.

Dissociative Experience Scale-II (DES-II)20This self-report scale is made up of 28 items designed to measure dissociative experiences in clinical and nonclinical populations when the subject is not under the effects of alcohol or drugs. This study used the Spanish version by Icarán et al.23 The items are answered on a percentage scale which measures the frequency the item described occurs in the subject's daily life (for example, “Some people have the experience of feeling that other people, objects, and the world around them are not real”), where 0% is never and 100% is always. For our purposes, the total scale score and the sum of the items that make up the DES-Taxon (3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 22, 27) were used to measure pathological dissociation.24 The Cronbach's alpha in this study was .94 for the total scale score and .84 for the DES-Taxon.

Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20)16This scale is a self-report inventory designed to measure somatoform dissociation in 20 items (for example, “I cannot see for a while, as if I am blind”) rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1: this applies to me not at all; 5: this applies to me extremely). In this study, the Spanish version by González-Vázquez et al.,25 which has good psychometric properties, was used. The Cronbach's alpha in this study was .86.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)26It is a self-report scale based on a single factor of full awareness, which evaluates the dispositional capacity for awareness or attention to experience at the moment in daily life. The Spanish version by Soler et al.27 was used. It is a 15-item self-report scale scored on a Likert scale of 1–6 (1: almost always, 6: almost never), for example, “I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until sometime later.” The Cronbach's alpha in this study was.88.

ProcedurePermission was requested from the authors for adaptation and translation of the scale. The items in the original version of the DCI were translated into Spanish following the recommendations of Muñiz et al.,28 using back-translation, with two translators, one familiar with the Spanish culture and the other familiar with the Anglo-Saxon culture. The first translated the questionnaire into Spanish and this version was then translated back into English by the second translator. These two versions were compared with the original English version for greater accuracy.

The scales were applied to a sample of participants from the community population and a sample of participants with psychiatric pathology who were users of the public mental health services in Seville (Spain). The community population sample was sent an email with a link created with Google forms in which they were explained the objectives of the study, an informed consent sheet, and a sheet on which they were asked for their sociodemographic and basic clinical information, and finally, the scales, in this order: DCI, SDQ 20, DES-II and MAAS. Each participant was assigned an alphanumeric code which was known only to the study researchers and no personal information was requested (name and last name) to safeguard anonymity. Fifteen days after the answers to the questionnaires had been received, they were sent a second email with another link with the DCI scale for the retest. The participants in the clinical sample were selected by their clinical referrals (clinical psychologist and psychiatrist) and were given the tests individually under adequate lighting and noise conditions. Before the scales were applied, all the participants in the clinical sample were also explained the objectives of the study and filled in the informed consent sheet. The tests were applied by two resident clinical psychologists trained in application of the scales. The order in which the tests were implemented and the time to retest were similar to the community population group.

Data analysisData analyses were performed with the SPSS v26 and LISREL v8.7 programs. A descriptive analysis was made of the sociodemographic variables as well as an analysis of skewness and Kurtosis of the items on the scale. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to calculate construct validity with robust maximum likelihood estimation (RML) to test the suitability of the internal test structure. The Satorra Bentler Scaled Chi-Square, non-normalized fit index (NNFI) and comparative fit index (CFI), which had to be>.90,29 were employed to check the overall fit of the models. In addition to these indices, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its confidence interval (CI) at 90%, which for good fit must be<.06, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which had to be<.0830 were also calculated.

The measurement invariance across groups (clinical and general populations) was tested using multi-group CFA. First, the fit indices of the DCI model were tested in each group separately (clinical population vs general population). Measurement invariance was evaluated on three levels: configural, metric and scalar.31 The fit of nested models was evaluated by comparing the CFI (ΔCFI) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA), using the recommended cut-off value of .01 for ΔCFI and .015 for ΔRMSEA.32

Evidence Based on Relations to Other Variables were studied with the Pearson correlation coefficient. Reliability DCI scores was analyzed with the ordinal alpha to calculate internal consistency and test–retest reliability at 15 days applying the test with the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Finally, the ROC curve was calculated to measure the sensitivity and specificity of the two DCI subscales and the total score.

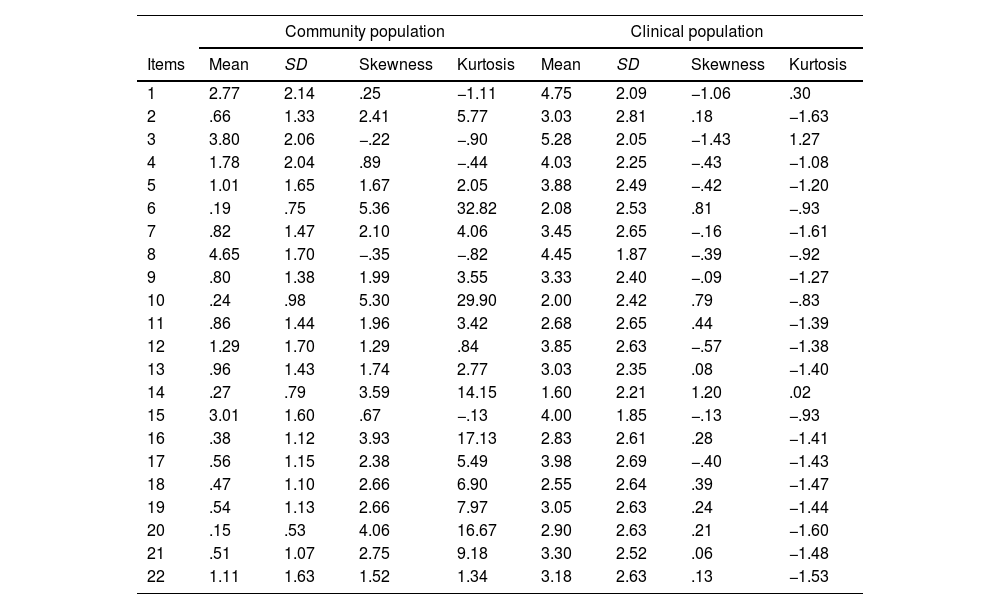

ResultsPreliminary analysisTable 2 shows the means, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis of each of the items on the DCI scale. The mean score found in detachment and compartmentalization in the clinical group was 3.76 (SD=1.57) and 3.03 (SD=1.69) respectively, and this difference was significant (t(39)=3.84, p<.001), and in the community population it was 1.57 (SD=1.07) and .53 (SD=.70) respectively, and this difference was also significant (t(267)=20.63, p<.001).

Descriptive statistics of the items on the DCI scale.

| Community population | Clinical population | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| 1 | 2.77 | 2.14 | .25 | −1.11 | 4.75 | 2.09 | −1.06 | .30 |

| 2 | .66 | 1.33 | 2.41 | 5.77 | 3.03 | 2.81 | .18 | −1.63 |

| 3 | 3.80 | 2.06 | −.22 | −.90 | 5.28 | 2.05 | −1.43 | 1.27 |

| 4 | 1.78 | 2.04 | .89 | −.44 | 4.03 | 2.25 | −.43 | −1.08 |

| 5 | 1.01 | 1.65 | 1.67 | 2.05 | 3.88 | 2.49 | −.42 | −1.20 |

| 6 | .19 | .75 | 5.36 | 32.82 | 2.08 | 2.53 | .81 | −.93 |

| 7 | .82 | 1.47 | 2.10 | 4.06 | 3.45 | 2.65 | −.16 | −1.61 |

| 8 | 4.65 | 1.70 | −.35 | −.82 | 4.45 | 1.87 | −.39 | −.92 |

| 9 | .80 | 1.38 | 1.99 | 3.55 | 3.33 | 2.40 | −.09 | −1.27 |

| 10 | .24 | .98 | 5.30 | 29.90 | 2.00 | 2.42 | .79 | −.83 |

| 11 | .86 | 1.44 | 1.96 | 3.42 | 2.68 | 2.65 | .44 | −1.39 |

| 12 | 1.29 | 1.70 | 1.29 | .84 | 3.85 | 2.63 | −.57 | −1.38 |

| 13 | .96 | 1.43 | 1.74 | 2.77 | 3.03 | 2.35 | .08 | −1.40 |

| 14 | .27 | .79 | 3.59 | 14.15 | 1.60 | 2.21 | 1.20 | .02 |

| 15 | 3.01 | 1.60 | .67 | −.13 | 4.00 | 1.85 | −.13 | −.93 |

| 16 | .38 | 1.12 | 3.93 | 17.13 | 2.83 | 2.61 | .28 | −1.41 |

| 17 | .56 | 1.15 | 2.38 | 5.49 | 3.98 | 2.69 | −.40 | −1.43 |

| 18 | .47 | 1.10 | 2.66 | 6.90 | 2.55 | 2.64 | .39 | −1.47 |

| 19 | .54 | 1.13 | 2.66 | 7.97 | 3.05 | 2.63 | .24 | −1.44 |

| 20 | .15 | .53 | 4.06 | 16.67 | 2.90 | 2.63 | .21 | −1.60 |

| 21 | .51 | 1.07 | 2.75 | 9.18 | 3.30 | 2.52 | .06 | −1.48 |

| 22 | 1.11 | 1.63 | 1.52 | 1.34 | 3.18 | 2.63 | .13 | −1.53 |

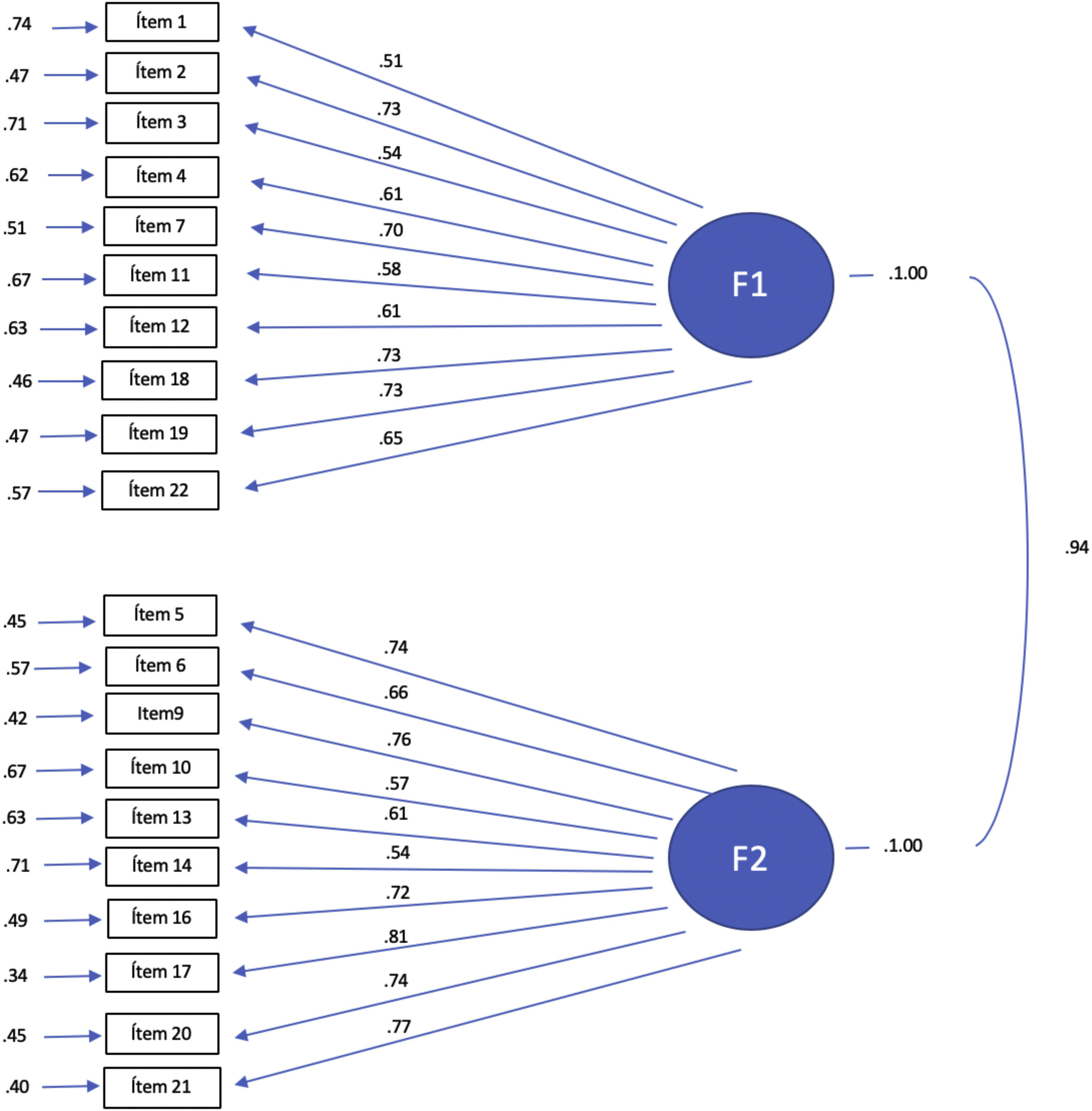

The CFA showed satisfactory fit to the two-factor model proposed by the original version of the DCI, with the following goodness-of-fit indicators: Satorra Bentler Scaled χ2(169)=318.04, p<.001; NNFI=.98, CFI=.99, RMSEA=.054 (90% IC=.044, .063), SRMR=.058. The results for the final model were 20 items of which 10 items (1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 11, 12, 18, 19 and 22) saturated on the Detachment factor and 10 items (5, 6, 9, 10, 13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21) on the Compartmentalization factor. The two validation items (8 and 15) were excluded from the CFA. Fig. 1 shows the CFA with the standardized factor weights.

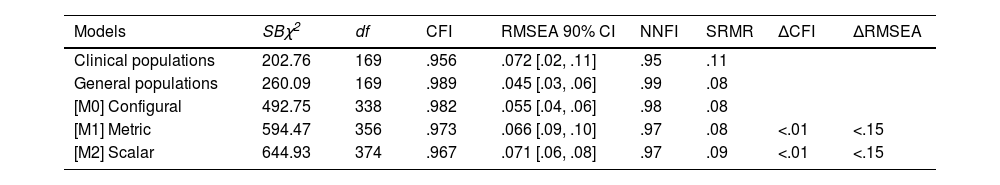

Measurement invariance of DCI across groups (patients and general populations)First, individual CFAs were carried out in each group to find the baseline model, and the goodness-of-fit indicators were found to be adequate (see Table 3). Multi-group CFA (MGCFA) was then performed on the DCI scale across groups. The configural invariance results (M0) revealed model good fit (CFI>.95 and RMSEA<.08), which shows that the factor structure is equivalent across patients and nonpatients. In continuation, an MGCFA was performed to test the metric invariance across groups (M1). The increase in CFI and RMSEA in the comparison between the M1 and M0 models did not exceed the recommended values, confirming the metric invariance. This shows that both patients and participants from the general population perceived and interpreted the items on the DCI in a similar manner. Finally, scalar invariance was tested (M2). When M2 was compared with M1, no significant increase was observed in the CFI or RMSEA indices, indicating that the dimensionality of the constructs was maintained across groups. These results show that the DCI structure, the relationship between the indicators of each variable and their respective latent factor, and the relationships among the latent variables were equivalent across groups.

Model fit indices for measurement invariance across groups.

| Models | SBχ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA 90% CI | NNFI | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical populations | 202.76 | 169 | .956 | .072 [.02, .11] | .95 | .11 | ||

| General populations | 260.09 | 169 | .989 | .045 [.03, .06] | .99 | .08 | ||

| [M0] Configural | 492.75 | 338 | .982 | .055 [.04, .06] | .98 | .08 | ||

| [M1] Metric | 594.47 | 356 | .973 | .066 [.09, .10] | .97 | .08 | <.01 | <.15 |

| [M2] Scalar | 644.93 | 374 | .967 | .071 [.06, .08] | .97 | .09 | <.01 | <.15 |

Note: SBχ2: Satorra–Bentler chi square; df: degrees of freedom; CFI: Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; NNFI: Non-Normed Fit Index; SRMR: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

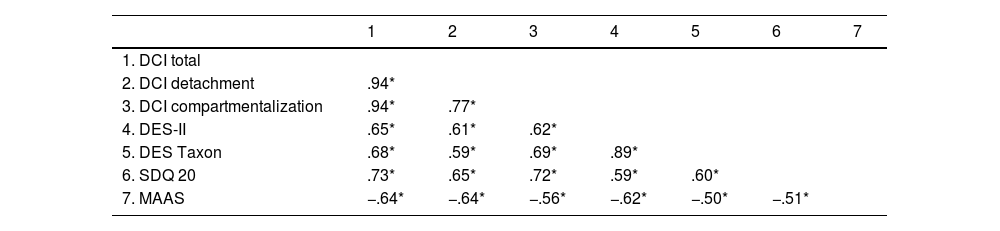

The evidence of validity based on relationships with other variables was calculated from the Pearson correlation coefficients. As observed in Table 4 concerning evidence of convergent validity, a positive correlation was found between the total DCI score and its two subscales with the DES-II, DES Taxon and SDQ 20, which measure all these different aspects of the dissociation construct (psychoform or somatoform).

Correlation matrix between DCI subscales and DES-II, DES-Taxon, SDQ and MAAS.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DCI total | |||||||

| 2. DCI detachment | .94* | ||||||

| 3. DCI compartmentalization | .94* | .77* | |||||

| 4. DES-II | .65* | .61* | .62* | ||||

| 5. DES Taxon | .68* | .59* | .69* | .89* | |||

| 6. SDQ 20 | .73* | .65* | .72* | .59* | .60* | ||

| 7. MAAS | −.64* | −.64* | −.56* | −.62* | −.50* | −.51* |

Note. N=308; DCI=Detachment and Compartmentalization Inventory; DES=Dissociative Experiences Scale; SDQ=Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire.

With respect to divergent validity evidence, a negative correlation was found between the two DCI subscales and the MAAS mindfulness scale. As may be seen in this table, the effect size of these correlations may be considered high as all of the coefficients are in the range of −.56 to −.73.

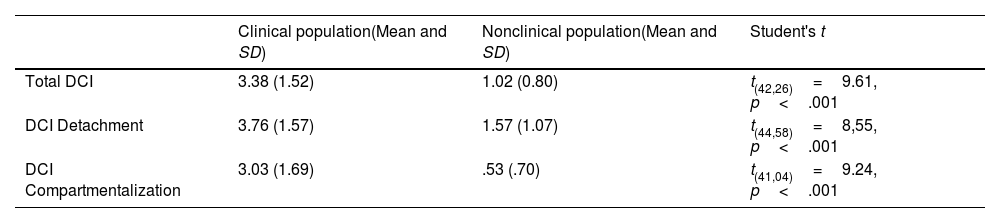

The Spanish version of the DCI discriminated between the participants in the general and clinical populations. As shown in Table 5, the mean scores for the total scale and the Detachment and Compartmentalization subscales were significantly higher in the clinical group.

Difference in mean scores on the DCI scale between the clinical and nonclinical populations.

| Clinical population(Mean and SD) | Nonclinical population(Mean and SD) | Student's t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total DCI | 3.38 (1.52) | 1.02 (0.80) | t(42,26)=9.61, p<.001 |

| DCI Detachment | 3.76 (1.57) | 1.57 (1.07) | t(44,58)=8,55, p<.001 |

| DCI Compartmentalization | 3.03 (1.69) | .53 (.70) | t(41,04)=9.24, p<.001 |

Note. N=308; DCI=Detachment and Compartmentalization Inventory.

Cohen's q test33 was applied to find out whether there were significant differences between the correlations of the DCI Detachment and Compartmentalization subscales and the other scales for measuring dissociation used in this study (DES-II, DES Taxon & SDQ-20, see Table 3). No significant effect size (q=.01) was found for the difference between the correlations in Detachment and Compartmentalization with respect to the DES-II, but there was small, but significant effect size with respect to the DES-Taxon and the SDQ-20, in which the effect size was greater for the Compartmentalization subscale (q=.17 and q=.13, respectively), showing that Compartmentalization was associated more strongly than Detachment with the DES Taxon, which measures pathological dissociation, and with the SDQ-20, which measures somatoform dissociation.

Estimation of DCI score reliabilityInternal consistency of the items on the DCI was studied using the ordinal alpha and its temporal stability with test-retest reliability. The ordinal alpha coefficient for the total score on the Spanish version of the DCI was .94. For the Detachment subscale it was .87 and for Compartmentalization it was .90. The test–retest was performed with 79% (243 participants) of the sample using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The test–retest between pre and posttest total scores was .81 (p<.001), for the Detachment subscale it was .75 (p<.001) and for Compartmentalization it was .81 (p<.001).

Calculation of the ROC curveThe receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was computed to analyze the sensitivity and specificity of the DCI subscales and its total score. The area under the ROC curve was statistically significant for the Detachment subscale (area=.87, p<.001, 95% CI [.82, .93]) showing a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 75% for a cutoff point of 17.50 points. On the Compartmentalization subscale, a significant area under curve was also found (area=.93, p<.001, 95% CI [.89, .97]) for a cutoff point of 9.50 with a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 81%. Finally, the area under the ROC curve for the total DCI score was also significant (area=.93, p<.001, 95% CI [.89, .97]) with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 84% for a cutoff point of 31.5 points.

DiscussionThe purpose of this study was to adapt and validate the DCI scale21 in a Spanish population. A CFA was performed to study the structural validity of the scale. The results confirmed the factor structure found in the original version corresponding to the “Detachment” and “Compartmentalization” factors described by other authors, such as Holmes et al.34 and Brown.13 The results of the final model were comprised of the same number of items as in the original study. The final model consisted of 10 items for each of the factors, plus two items in the validation scale. The analysis of invariance showed that patients and participants from the general population had an equivalent interpretation of the items on the DCI scale.

In the Spanish version of the DCI, we kept Item 8 and 15 from validation of the original test in English. The criterion of application consisted in eliminating those participants who scored 0 on those items. The result was that a large number of subjects (86) had to be excluded from the study since their answers were not considered to be sincere, and therefore, could have affected the overall response of the inventory. This study did not provide clear enough information to determine whether these validation items enabled discrimination between valid and invalid answers to the test, and it would therefore be of interest in future to study the adequacy of these items.

The results on evidence of convergent validity were also similar to those for the original version. The two subscales of the Spanish version of the DCI showed high positive correlations with other scales that measure both psychoform (DES-II and DES-Taxon) and somatoform (SDQ-20) dissociation. This means that a high score on this scale is associated with a high score on the scales that measure dissociative symptoms in which psychological processes are altered as well as dissociative symptoms affecting the body.16 It also shows that the DCI scale has ample coverage and includes a wide diversity of dissociative experiences.

With regard to evidence of divergent validity, negative correlations were found between the scores on the DCI subscales and the MAAS mindfulness scale, which measure opposite constructs. This result is coherent with other studies done both in general and psychiatric populations (more specifically with other studies in psychosis) in which a negative correlation was found between mindfulness and dissociation in general,35 mindfulness and depersonalization36 and mindfulness and depersonalization and absorption.37

Similarly, for evidence of construct validity, on one hand, we found no differences in the strength of the association between the two DCI subscales and the total score on the DES-II, but on the other, there were differences in the association with the DES-Taxon and the SDQ-20. That is, the effect size of the correlation between Compartmentalization, pathological and somatoform dissociation is greater than the effect size found between these scales and the subscale measuring detachment. This result is coherent with the idea that compartmentalization measures a more severe type of dissociative experience qualitatively different from detachment-type dissociation. Furthermore, it is also coherent with the hypothesis of some authors which affirms that somatoform symptoms are more associated with compartmentalization.16

The results also showed that the scores on the Spanish version of the DCI discriminated between the participants in the clinical group and those without a psychiatric diagnosis. Similar to the original study, the scores found with this scale enable discrimination between the two populations, but in addition, the Spanish version showed adequate sensitivity and specificity, with cutoff points that make it possible to estimate whether the degree of dissociation is pathological or not. Finally, the DCI scale scores also show adequate internal consistency (with values from .87 to .90) and test-retest reliability scores, so it may be inferred that it is a reliable scale, and that it also enables temporal follow-up with repeated measures over time.

The DCI scale can be very useful in both the clinic and research. Differentiation between detachment and compartmentalization constructs can facilitate more exhaustive evaluation of clinical cases, and therefore, make therapeutic formulations better adjusted to the pathology and patient needs. It is also an instrument which can contribute to studying the efficacy of current treatments designed for dissociation, since it can enable evaluation better adjusted to the type of dissociative experience. It can further be used in studying the role of different types of dissociative experiences in psychopathological processes, such as anxiety, depression and obsessive disorders,38 or hallucinations in patients with psychosis37 in which detachment-type dissociation seems to have a relevant role.

Nevertheless, although the results point to confirmation of the DCI as a valid and reliable scale for studying dissociative phenomenology, some limitations should be borne in mind. There are several limitations having to do with the sample and participant selection: they were not found by random, and so there could be a bias in their recruitment. The sample was not very large, and a considerable number of subjects were excluded from both groups because they scored zero on the validity items. Furthermore, although the participants in the psychiatric pathology group were referred by their therapists (clinical psychologists or psychiatrists), their diagnoses could not be precisely confirmed. Moreover, as the scales used were the self-report type, the answers could have been biased by social desirability, distorted memories or even difficulty in understanding some of the items due to the uniqueness of this type of experience. In addition, antecedents of mental disorders in family members was not explored in the sample of the general population. Finally, and as the authors correctly mention in the original version of the DCI,21 its validity for distinguishing between and belonging to the detachment and compartmentalization constructs might be questioned, due to the current debate on the dissociation concept itself (e.g., Dell39). In any case, we believe that this scale can contribute positively to this debate by providing information than can be helpful in understanding dissociation and its underlying mechanisms.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank Dr. Martin Dorahy for his help and support in performing this study.

Virgen del Rocío Outpatient Mental Hospital, Andalusian Health-Care Service, Avda. Jerez, s/n, 41013 Seville, Spain.

Department of Psychology, University of Cádiz, Spain; Ave. República Árabe Saharaui S/N. 11510, Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain.

Personality, Evaluation and Psychological Treatment Department, University of Seville, Camilo José Cela, SN, 41018 Seville, Spain.

Virgen del Rocío University Hospital/ University of Seville/ IBiS/ CIBERSAM, Avda. Manuel Siurot, s/n, 41013 Seville, Spain.