Mental healthcare needs among individuals in recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection is relevant for healthcare planning because mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment are common after acute COVID-191 and can be responsible of a large proportion of the burden of disability attributed to persisting COVID-19 (“long covid”) symptoms.2 Estimating the mental healthcare requirements during the year following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection is critical to guide mental healthcare planning and resource allocation, especially in pandemic hotspots.

We used electronic health records to retrieve data on all patients aged 16 or more who were admitted due to COVID-19 to a large teaching hospital in Madrid for ≥24h between March 16th and April 15th, 2020. Of note, the March 16th 7-day cumulative incidence rate of COVID-19 in Madrid (Spain) was 253 per 100,000 citizens (almost three times that of New York City) and critical care bed requirements had increased by five-fold.3 Following discharge, COVID-19 patients were routinely screened for mental health problems and referred to a COVID-19 mental health unit if mental health complications during admission or after discharge were present. We retrieved: (i) sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, (ii) hospitalization-related variables, and (iii) mental health requirement variables after hospital discharge. A total 430 COVID-19 inpatients died during admission and 1455 were discharged (study sample) (see Table 1). A full description of the study setting, design, participants, and statistical analysis is provided in the supplementary material.

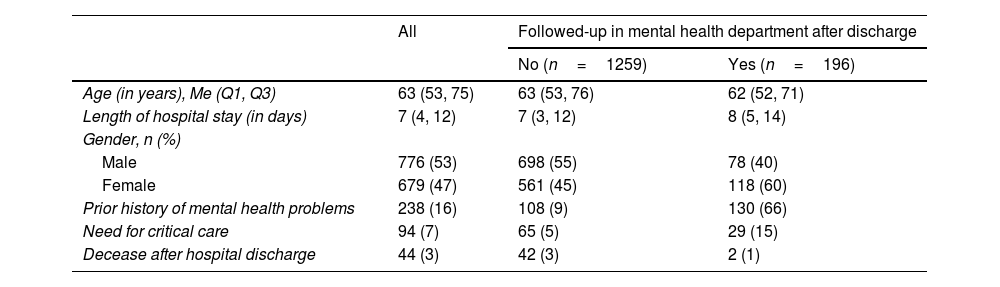

Characteristics of the participants (n=1455).

| All | Followed-up in mental health department after discharge | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=1259) | Yes (n=196) | ||

| Age (in years), Me (Q1, Q3) | 63 (53, 75) | 63 (53, 76) | 62 (52, 71) |

| Length of hospital stay (in days) | 7 (4, 12) | 7 (3, 12) | 8 (5, 14) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 776 (53) | 698 (55) | 78 (40) |

| Female | 679 (47) | 561 (45) | 118 (60) |

| Prior history of mental health problems | 238 (16) | 108 (9) | 130 (66) |

| Need for critical care | 94 (7) | 65 (5) | 29 (15) |

| Decease after hospital discharge | 44 (3) | 42 (3) | 2 (1) |

Note: Me: median; Q1: first quartile (percentile 25); Q3: third quartile (percentile 75).

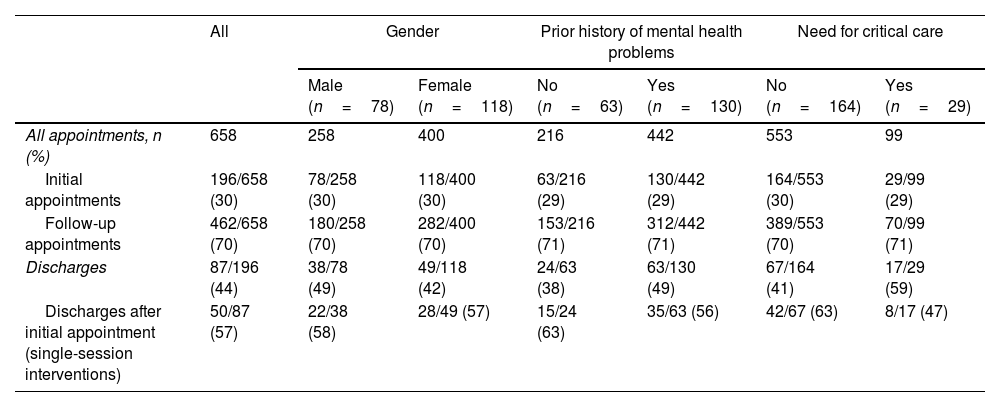

Over the 1-year follow-up period, 196 (14%) presented to the mental health services after being discharged, mostly with anxiety, depression, and/or acute stress symptoms (n=145, 75%). This result is markedly higher than the 1-year estimate of the use of mental health services in 2002 across two representative samples in Spain (3.6%)4 and in Europe (6.4%),5 and consistent with the finding that one in four hospitalized COVID-19 patients had anxiety and/or depressive symptoms over a 1-year follow-up period.1 Importantly, we may have underestimated the actual number of mental health appointments, as informal consultations (e.g., between healthcare workers6) and consultations outside the public National Health System (e.g., private clinics) were not registered. We also found that roughly half of the patients followed by the mental health outpatient service (87/196, 44%) were discharged over the follow-up period (26% after a single-session intervention) (see Table 2). The average direct medical cost for mental health care was EUR 48 per patient; average costs were EUR 195 and EUR 19 per patient with and without prior mental health history, respectively, and EUR 110 vs. EUR 43 per patient who required or did not require critical care during admission, respectively. Kaplan–Meier estimates of the probability of consulting with the mental health department after being discharged from COVID-19 hospitalization showed that women, patients with prior history of mental health problems, and patients who required critical care during hospitalization were more likely to receive mental health care, and that the probability of having an outpatient mental health visit increased over the follow-up period. Although these are crude estimators from bivariate comparisons, they are consistent with pre-pandemic findings.4,5,7

Frequency of mental health requirements after hospital discharge (n=196).

| All | Gender | Prior history of mental health problems | Need for critical care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=78) | Female (n=118) | No (n=63) | Yes (n=130) | No (n=164) | Yes (n=29) | ||

| All appointments, n (%) | 658 | 258 | 400 | 216 | 442 | 553 | 99 |

| Initial appointments | 196/658 (30) | 78/258 (30) | 118/400 (30) | 63/216 (29) | 130/442 (29) | 164/553 (30) | 29/99 (29) |

| Follow-up appointments | 462/658 (70) | 180/258 (70) | 282/400 (70) | 153/216 (71) | 312/442 (71) | 389/553 (70) | 70/99 (71) |

| Discharges | 87/196 (44) | 38/78 (49) | 49/118 (42) | 24/63 (38) | 63/130 (49) | 67/164 (41) | 17/29 (59) |

| Discharges after initial appointment (single-session interventions) | 50/87 (57) | 22/38 (58) | 28/49 (57) | 15/24 (63) | 35/63 (56) | 42/67 (63) | 8/17 (47) |

Note: Denominators used to calculate proportion vary across variables and strata: the proportion of initial and follow-up appointments is based on the total number of appointments, the proportion of discharges is based on the number of initial appointments (i.e., number of patients seen by the mental health services), and the proportion of discharges after the initial appointment is based on the total number of discharges.

Our results can help design mental health screening and referral protocols tailored for vulnerable groups that reduce the burden of mental health problems among severe COVID-19 patients and may inform short- and mid-term service planning for current and future pandemics. For instance, people with prior history of mental health problems were more likely to consult with mental health professionals after discharge.8 Early referrals to mental health services for screening or prompt follow-up appointments with their usual care providers may help prevent mid- and long-term mental health problems. People with critical care requirements also had greater odds of seeing a mental health professional after discharge, and they may beneficiate from routine screenings in primary care to detect the mental health consequences of the post-intensive care syndrome and of the COVID-19 itself.9,10 Last, our findings are in line with long-standing observations showing that women are both more vulnerable to reporting mental health problems and more likely to attend mental health services – reasons for these gender differences in this setting remain elusive despite implications for mental health service planning.

FundingThis work was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme Societal Challenges (grant number: 101016127) and by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (grant numbers: COV20/00988, PI17/00768, and PI19/00941) and co-funded by the European Union.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

The authors thank the medical students who worked on the dataset and all COVID@HULP collaborators.