The world is currently undergoing an extremely stressful scenario due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This unexpected and dramatic situation could increase the incidence of mental health problems, among them, psychotic disorders. The aim of this paper was to describe a case series of brief reactive psychosis due to the psychological distress from the current coronavirus pandemic.

Materials and methodsWe report on a case series including all the patients with reactive psychoses in the context of the COVID-19 crisis who were admitted to the Virgen del Rocío and Virgen Macarena University Hospitals (Seville, Spain) during the first two weeks of compulsory nationwide quarantine.

ResultsIn that short period, four patients met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for a brief reactive psychotic disorder. All of the episodes were directly triggered by stress derived from the COVID-19 pandemic and half of the patients presented severe suicidal behavior at admission.

ConclusionsWe may now be witnessing an increasing number of brief reactive psychotic disorders as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This type of psychosis has a high risk of suicidal behavior and, although short-lived, has a high rate of psychotic recurrence and low diagnostic stability over time. Therefore, we advocate close monitoring in both the acute phase and long-term follow-up of these patients.

El mundo está experimentando un escenario extremadamente estresante a causa de la pandemia del COVID-19. Esta situación inesperada y dramática podría incrementar la incidencia de los problemas de salud mental y, entre estos, los trastornos psicóticos. El objetivo de este documento es describir una serie de casos de psicosis reactiva breve, debidos al distrés psicológico debido a la pandemia actual de coronavirus.

Materiales y métodosReportamos una serie de casos que incluye a todos los pacientes con psicosis reactiva en el contexto de la crisis del COVID-19, ingresados en los Hospitales Universitarios Virgen del Rocío y Virgen Macarena (Sevilla, España) durante las 2 primeras semanas de la cuarentena obligatoria a nivel nacional.

ResultadosEn este breve espacio de tiempo, 4 pacientes cumplieron los criterios de trastorno psicótico breve del manual diagnóstico y estadístico de trastornos mentales (DSM-5). Todos los episodios fueron desencadenados por el estrés derivado de la pandemia del COVID-19, y la mitad de los pacientes presentaron un comportamiento suicida grave a su ingreso.

ConclusionesActualmente podemos estar asistiendo a un incremento del número de trastornos psicóticos reactivos breves, como resultado de la pandemia del COVID-19. Este tipo de psicosis tiene un elevado riesgo de comportamiento suicida y, aunque es transitorio, tiene una elevada tasa de recurrencia psicótica y baja estabilidad diagnóstica a lo largo del tiempo. Por tanto, somos partidarios de una supervisión estrecha tanto en la fase aguda como en el seguimiento a largo plazo de estos pacientes.

The classical concept of reactive psychosis, also called psychogenic psychosis, encompasses a set of acute onset and short-lived psychotic conditions triggered by psychological trauma.1 This nosological entity as well as other traditional descriptions, such as bouffée délirante, cycloid psychosis or atypical psychosis, have limited validity and do not constitute independent diagnostic categories in modern psychiatric classifications.1 However, reactive psychoses are subsumed in the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) under the category, “acute and transient psychotic disorders” (ATPD) with the specifier ‘with associated acute stress’ (F23.x1),2 and in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), under the category “brief psychotic disorder” (BPD; 298.8) with the specifier “with marked stressor(s)”.3

The world is presently experiencing an exceptional situation, without any doubt extremely stressful, because of COVID-19. This ongoing public health crisis is the most serious since the 1918 influenza pandemic, which was the deadliest pandemic of the 20th century and had a devastating psychological impact across the globe.4 Spain is one of the countries most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore, the government has declared a national state of emergency, ordering limited movement of its citizens within the country and home confinement of the population in the framework of a national quarantine without precedent.5 These dramatic circumstances could lead to an increase in mental disorders in our population, among them episodes of brief reactive psychosis. However, a review of the literature showed that research on the role of pandemics in the onset of reactive psychosis in the general population is scarce.6 The aim of this report was to describe a case series of reactive BPD under the state of emergency in our country due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methodsWe report a case series including all consecutive patients aged 18–65 with brief reactive psychoses in the context of the COVID-19 crisis who were admitted to the Virgen del Rocío and Virgen Macarena University Hospitals (Seville, Spain) during the first two weeks of compulsory nationwide quarantine (from 14th to 28th March 2020). Both hospitals collectively cover a catchment area of approximately 1.5 million people from different sociodemographic backgrounds who are representative of the population served by public health services in Andalusia (Southern Spain). Organic, affective and substance-induced psychoses were ruled out. Other exclusion criteria were being COVID-19 positive or having symptoms of respiratory infection. Diagnosis of brief reactive psychosis was made according DSM-5 criteria for BPD.3 The case series was reported following the recommendations outlined in the CAse REport (CARE) guidelines7 and was approved by the Andalusian Biomedical Research Ethics Committee. All patients gave their informed consent to publish this report.

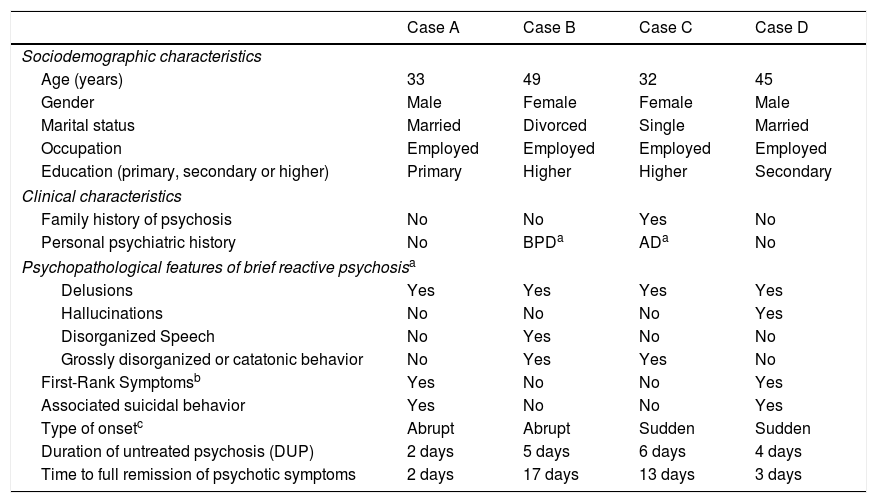

ResultsDuring the abovementioned period, the following four patients were admitted for acute reactive psychosis caused by stress from the coronavirus pandemic. Their psychotic symptoms occurred in response to the fear of contagion (to themselves or their loved ones), the compulsory home-confinement or concerns about the economic consequences of the lockdown (such as job loss). All met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for BPD with marked stressors at hospital discharge.3Table 1 shows patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| Case A | Case B | Case C | Case D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 33 | 49 | 32 | 45 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Female | Male |

| Marital status | Married | Divorced | Single | Married |

| Occupation | Employed | Employed | Employed | Employed |

| Education (primary, secondary or higher) | Primary | Higher | Higher | Secondary |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Family history of psychosis | No | No | Yes | No |

| Personal psychiatric history | No | BPDa | ADa | No |

| Psychopathological features of brief reactive psychosisa | ||||

| Delusions | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hallucinations | No | No | No | Yes |

| Disorganized Speech | No | Yes | No | No |

| Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| First-Rank Symptomsb | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Associated suicidal behavior | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Type of onsetc | Abrupt | Abrupt | Sudden | Sudden |

| Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) | 2 days | 5 days | 6 days | 4 days |

| Time to full remission of psychotic symptoms | 2 days | 17 days | 13 days | 3 days |

Abbreviations: AD, adjustment disorder; BPD, brief psychotic disorder.

Schneiderian first-rank symptoms include: (i) thought withdrawal, insertion and interruption; (ii) thought broadcasting; (iii) hallucinatory voices giving a running commentary on the patient's behavior, or discussing the patient among themselves; (iv) somatic hallucinations; (v) feelings or actions experienced as made or influenced by external agents; and (vi) delusional perception

Mr. A is a 33-years-old married man with no personal or family history of mental health problems who was hospitalized due to an abrupt psychotic episode with suicidal behavior. In the context of home-confinement and concerns about losing his job because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the patient developed a paranoid psychosis in which he believed that his loved ones were being controlled by machines and that the end of the world was coming. The suicide attempt was in response to such psychotic experiences. He was treated with 10mg/day olanzapine and in 48h, psychotic and suicidal symptoms had completely disappeared.

Case BMrs. B is a 43-year-old divorcee with a previous history of two BPD episodes (both reactive to stressful life events) who was hospitalized due to a new psychotic relapse, this time related to distress caused by the COVID-19 crisis. Her symptoms, disorganized speech and behavior, emotional turmoil, marked irritability and delusions about her family being infected by coronavirus, had an abrupt onset and were triggered as a result of the enforced home-confinement. The patient was given 30mg/day aripiprazole and 4mg/day clonazepam, and her psychotic symptomatology progressively improved until full remission three weeks later.

Case CMiss C is a 32-year-old single woman with a past history of adjustment disorder who was transferred to our hospital because of an acute episode of psychosis related to the pandemic. Since the beginning of the state of emergency, the patient had started to be extremely worried about the possibility of being a contagious asymptomatic carrier of coronavirus. On the night of admission, she had gone to another hospital with the delusional conviction that a friend of hers had died from COVID-19, and once there, experienced an episode of severe agitation. During the first interview, perplexity, overwhelming anxiety, suspiciousness, and marked self-referentiality were noted. She was treated with 20mg/day aripiprazole and 3mg/day lorazepam, and psychotic symptoms progressively disappeared until full remission over the course of two weeks.

Case DMr. D is a 45-year-old married man with no personal or family history of psychiatric disorders, who was admitted after attempting suicide in the context of acute psychosis. One week prior to admission, he had begun to feel distressed about the pandemic and started obsessively checking the worldwide COVID-19 death toll. In the following few days, the patient developed the delusional conviction that the Illuminati were behind the pandemic and schizophrenia-like symptomatology in which he could hear his neighbors’ voices making running commentaries on his own thoughts. He attempted suicide because he believed he was going to be tortured. After receiving 1.5mg/day risperidone and 2mg/day lorazepam, psychotic symptoms rapidly remitted in 72h.

DiscussionThis paper reports on a case series of BPD triggered by psychological distress derived from the current COVID-19 pandemic. Other authors have reported cases similar to ours, and it is likely that this could be a generalized phenomenon in countries severely affected by the coronavirus pandemic.6 Thus, these exceptional circumstances being experienced around the world could lead to a significant increase in the incidence of psychotic disorders. In fact, there is already preliminary evidence in this respect in China, the country where the pandemic originated, and where an increase in the number of cases of first-episode schizophrenia has been observed in the months since the outbreak of COVID-19.8

The current pandemic, as other public health crises recently experienced, such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or Ebola, is leading to negative psychological effects in the population, not just because of fear of infection, but usually also because of the Government implementation of isolation and quarantine measures to avoid the spread of the disease.9 Such imposed home confinement restricts the freedom, routines and rhythm of conventional life and involves forced separation from family and friends that causes an increase in uncertainty about the unknown, as well as an overall feeling of loss of control.9 The fear of stigmatization and financial loss may substantially enhance this emotional distress in the population.9 Moreover, in today's age of digital information and social networks, the proliferation of fake news and conspiracy theories would contribute even further to increasing worry and social alarm.6

This acutely stressful scenario could play a relevant role in the genesis of new-onset psychoses and might also be an important risk factor for clinical decompensation in individuals with previous psychotic disorders.10 The relationship between adult life events and subsequent onset of psychosis has received little attention by researchers, although meta-analytical evidence suggests around a threefold increase in risk of psychosis in those experiencing stressful events.11 The presence of these adverse psychosocial factors is also associated with higher frequency in the development of brief psychotic disorders than with schizophrenia or affective psychosis.1 Along this line, emotional reactivity to stress constitutes the substrate underlying the concept of brief reactive psychosis.1 Thus, in keeping with stress-diathesis models,12 the emergence of psychotic symptoms in these individuals with reactive psychosis might be associated not only with the acute stress related to the COVID-19 crisis (which would act as a stressor or state-dependent characteristic) but also with preexisting psychological or biological abnormalities (that would act as susceptibility or trait-like diathesis).

With regard to the description above, it should be noted that the increased emotional reactivity observed in individuals with brief reactive psychosis could also render them more vulnerable to impulsive behavior and lead to suicidal ideation when they must deal with highly stressful events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In this vein, acute stress has been significantly associated with an increase in risk of suicide in persons with short-lived psychotic disorders,13 and suicidal behavior has also been reported under forced quarantine similar to what we are now experiencing.9 Therefore, it is paramount to assess suicidal symptoms in this population with brief reactive psychosis, especially in emergency settings where this task can often be passed over because of the rapidly changing psychopathology in such clinical cases.12

Other important points to keep in mind are the risk of recurrence and the diagnostic instability of such short-lived psychotic disorders.14 Although brief reactive psychoses have traditionally been considered clinical conditions with good prognosis, in almost half of such cases, their evolution over time is toward severe mental disorders, mostly schizophrenia or, to a lesser extent, bipolar disorder.1,14 The presence of hallucinations and schizophreniform symptomatology at the onset of psychosis, as well as later relapse, are factors associated with an increased risk of developing chronic psychotic disorders during follow-up.15,16 Moreover, long hospitalizations and the prescription of high dosages of antipsychotic medication seem to be predictors of poor prognosis in these short-lived psychotic disorders.17,18 It would therefore be necessary to prepare preventive approaches and close follow-up of this population with reactive psychosis when the COVID-19 crisis has ended, due to the abovementioned risk of recurrences and transition to long-lasting psychotic disorders of these individuals.

Summarizing, we conclude that the current COVID-19 pandemic and the mandatory nationwide quarantine enforced by authorities to control spread of the virus constitute a risk factor for the development of reactive psychoses. Such psychotic conditions are associated with a high risk of suicide, high rate of relapse and low diagnostic stability, making close clinical monitoring necessary in both the acute phase and in long-term follow-up.

Role of the funding sourceThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone.

We would like to thank the patients for allowing us to publish details of their cases.