This study assessed the treatment preferences among Latin American psychiatrists for their bipolar disorder patients and if these preferences reflect the current guidelines.

MethodsWe designed a survey comprised of 14 questions. All the questions were aimed at the treatment of bipolar I patients only. We distributed the survey by hand or e-mail to psychiatrists in eight different countries: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, México, Perú and Venezuela. Between May 2008 and June 2009, we were able to gather 1143 surveys.

ResultsAs the initial choice of treatment for a bipolar patient who debuts with mania, 61.3% choose a combination of an atypical antipsychotic and a mood stabilizer. Lithium carbonate (50%) was the first choice for a mood stabilizer in a manic episode. Olanzapine (55.4%) was the initial antipsychotic of choice for the treatment of acute mania. For the treatment of acute bipolar depression, 27% choose Lamotrigineas their first choice. Most of the psychiatrists (74.8%) prescribe antidepressants for the treatment of bipolar depression. For maintenance treatment of bipolar depression most psychiatrists’ first choice would be Lamotrigine (50.3%). Most of the psychiatrists (89.1%) prescribed two or more psychotropic drugs for the maintenance treatment of their bipolar patients.

ConclusionsThere were some similarities with the studies previously done in the US. It seems that for the most part the Latin American psychiatrists do not strictly follow the literature guidelines that are published, but rather adapt the treatment to the specific case. More longitudinal studies of prescribing patterns in bipolar disorder are needed to corroborate these findings.

Este estudio evaluó la preferencia farmacológica de los psiquiatras latinoamericanos para tratar a sus pacientes con trastorno bipolar y si estas preferencias se adecuan a las guías actuales de tratamiento publicadas.

MétodosSe diseñó una encuesta que comprendía catorce preguntas. Todas las preguntas estaban dirigidas al tratamiento de pacientes con trastorno bipolar tipo I solamente. Distribuimos la encuesta a psiquiatras de ocho diferentes países: Argentina, Brasil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, México, Perú y Venezuela. Entre mayo del 2008 y junio del 2009 recolectamos 1.143 encuestas.

ResultadosComo la elección inicial de tratamiento para un paciente que debuta con manía, un 61,3% escogieron una combinación de un antipsicótico atípico y un eutimizante. Carbonato de litio (50%) fue la primera elección para un eutimizante en un episodio de manía aguda. Olanzapina (55,4%) fue la primera elección para un antipsicótico en el tratamiento de manía aguda. Para el tratamiento de depresión bipolar aguda, un 27% escogieron lamotrigina como primera opción. La mayoría de los psiquiatras (74,8%) utiliza antidepresivos para el tratamiento de depresión bipolar. Para la prevención de futuros episodios de depresión bipolar, la primera elección fue lamotrigina (50,3%). La mayoría de los psiquiatras (89,1%) prescriben dos o más psicofármacos para el tratamiento de mantenimiento de sus pacientes bipolares.

ConclusionesSe encontraron similitudes con estudios previos realizados en Estados Unidos. Parece que los psiquiatras latinoamericanos no siguen estrictamente las guías de tratamiento, sino que adaptan el tratamiento al caso individual. Se necesitan más estudios longitudinales en pacientes bipolares en Latinoamérica para corroborar estos resultados.

Bipolar disorder can be a devastating illness for those who suffer it and their families. An early and adequate treatment can provide not only a complete control of the symptoms but also a better prognosis.1,2 In recent years there has been a growing increase in available treatment options and the medication regimens have become more complex and challenging. There are also published a number of available guidelines that can help physicians in making treatment decisions. Despite this, the evidence suggests that these guidelines are often not followed by many psychiatrists in clinical practice.3,4One example of this is the fact that antidepressants are frequently used to treat bipolar depression, even so they are not approved by the FDA to treat bipolar disorder.5,6 The use of antidepressants, especially as monotherapy, carries the risk of possible serious complications in the immediate future. There is the possibility of switch to the opposite pole, the induction of rapid cycling, or altering the course and frequency of futures episodes.7,8 One of the predictors for the risk for switching is the presence of subsyndromal manic/hipomanic symptoms during a depressive episode.9 There is still a great deal of controversy on whether antidepressants are effective for the treatment of bipolar depression.10–12

With more than 20 countries and over 600 million people, Latin America represents a unique opportunity for research given the remarkable similarity in culture and illness presentation.

In Latin America most of the available literature for the treatment of this illness comes from the northern hemisphere. With some notable exceptions, there is very little research done in Latin America to better understand this illness and which psychotropic drugs are choose to treat these patients.

There are some studies done in the U.S. who examined the patterns of psychotropic drug prescription in bipolar disorder patients.5,13–20 Most of these studies suggested that Lithium and Valproate are the most common prescribed medications, with over 50% of the bipolar patients receiving one of them. They also showed that at least half of the patients were prescribed antidepressants, sometimes without a mood stabilizer. In these studies monotherapy was the exception rather than the rule, with over 80% of patients receiving more than one psychotropic. There is even a study in elderly adults with bipolar disorder that showed similar results to that of the younger population.21

To our knowledge there are no published studies which examined the same topic in Latin American patients. There is one Latin American study that looked at treatment outcomes with different medications for bipolar disorder patients and mentioned which medications were the patients taking at study entry. In this case the pattern of prescription was more similar to that of the European countries than to the US.22

Our objective was to answer the following questions: given different questions, what are the treatment preferences among Latin American psychiatrists for their bipolar disorder patients? Do these preferences reflect the current literature and guidelines? We believe that this information is very important to help us understand how our bipolar disorders patients in Latin America are treated and what are the possible similarities and differences with the treatments in other parts of the world. Furthermore, this is the first step in also understanding the reasons for choosing a specific treatment. We can learn from it, in order to improve as much as we can the treatment for this serious illness.

MethodsIn order to accomplish our objective we designed a survey comprised of 14 questions. We carefully choose the questions that will give us the most information on treatment preferences. All the questions were aimed at the treatment of bipolar I patients only. The last four questions of the survey were demographical, so we could be sure that the sample adequately represents the total universe.

The survey was completely anonymous and there was no funding involved from any government or pharmaceutical company. All the questions were multiple choices. We distributed the survey by hand or e-mail to the highest possible number of psychiatrists in eight different countries: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, México, Perú and Venezuela. The response rate was much higher when distributed by hand that when distributed by e-mail (80% vs 20% in average). Between May 2008 and June 2009, we were able to gather 1143 surveys from these eight countries. This number represents approximately the 12% of all the psychiatrists in the above mentioned countries. Each country was represented for at least the 10% of all their psychiatrists. All the surveys were examined and tabulated.

ResultsOf the total sample of 1143 psychiatrists who answered the survey, 57.4% were male and 42.6% were female. In terms of experience, 64% of the psychiatrists have been treating psychiatric patients for at least 10 years. But also a significant 18.5% had less than five years of practice in the field. Most of the psychiatrists (47.2%) work in both the private and public sectors, while the 33.9% work only in private practice.

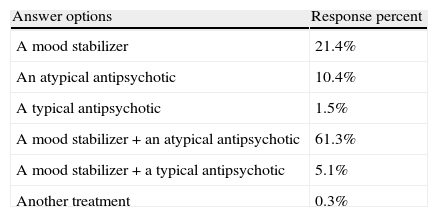

When asked what would be your initial choice of treatment for a bipolar patient who debuts with mania, 61.3% choose a combination of an atypical antipsychotic and a mood stabilizer, while 21.4% choose only a mood stabilizer as monotherapy (Table 1). Lithium carbonate (50%) and Valproic acid (41.6%) were by far the choices when asked what would be your first mood stabilizer of choice for a bipolar patient with a manic episode. The remaining options were carbamazepin (3.6%) and ozcarbamazepin (1.7%).

Which would be your first choice of treatment in a patient who debuts with a manic episode and you suspect bipolar disorder?

| Answer options | Response percent |

| A mood stabilizer | 21.4% |

| An atypical antipsychotic | 10.4% |

| A typical antipsychotic | 1.5% |

| A mood stabilizer+an atypical antipsychotic | 61.3% |

| A mood stabilizer+a typical antipsychotic | 5.1% |

| Another treatment | 0.3% |

When asked what would be your first choice of an atypical antipsychotic for a manic episode in a bipolar patient, 55.4% choose Olanzapine, 22.1% Quetiapine, and 17.2% Risperidone. Aripiprazole (2.4%) and Ziprasidone (0.9%) were barely choose. Again, Lithium carbonate (36.6%) and Valproic acid (33.5%) were the most common choices when asked what is the most frequent psychotropic drug that you prescribed for maintenance treatment in a bipolar patient. Lamotrigine and an atypical antipsychotic were somewhat behind with 13.2% and 11.6%, respectively.

Most of the psychiatrists (78.5%) do not prescribe depot antipsychotic medication for their bipolar patients.

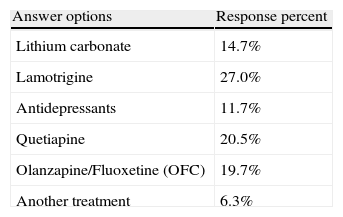

When asked what would be your first choice of treatment for a patient with acute bipolar depression, 27% choose Lamotrigine, 20.5% Quetiapine, 19.7% the combination Olanzapine/Fluoxetine, 14.7% Lithium carbonate and 11.7% an antidepressant (Table 2).

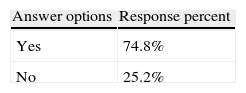

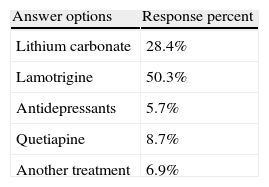

Most of the psychiatrists (74.8%) prescribe antidepressants at some point for the treatment of their patients with bipolar depression (Table 3). If they have to prescribe an antidepressant most will use SSRIs (58%) and then Bupropion (25.4%). In terms of maintenance treatment for bipolar depression most psychiatrists first choice would be Lamotrigine (50.3%) followed by Lithium carbonate (28.4%) (Table 4). Finally, most of the psychiatrists (89.1%) prescribed, in average, two or more psychotropic drugs for the maintenance treatment of their bipolar patients.

The sample faithfully represents the total universe of psychiatrists, at least in the eight countries involved, in terms of gender, type of practice and years of experience in the field.

We believe it was important to make a difference in terms of public vs private practice because the health system in Latin American countries is very different from the northern hemisphere.

Practically all of the private insurances will not cover mental health care or psychotropic medications. Most of the public institutions do not have the appropriate resources in terms of manpower and medications. A significant number of patients have to pay out of pocket for their treatment. This might explain why there is still a place for the typical antipsychotic drugs and why Lithium carbonate is a common choice.

We were not surprised to find that Lithium was a common choice because it is a very effective treatment for many patients. In addition Lithium is the only medication that has shown a protective effect in preventing suicide attempts in bipolar patients.23–25 In Latin America it has been widely used as a first choice for the past 35 years.

The first interesting result was to find out whether two thirds of the psychiatrists will start their acute manic patient with a combination of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic, rather than use monotherapy. Not only that, but we also found that almost 90% of the bipolar patients are receiving, in average, two or more psychotropic drugs for maintenance treatment.

In accordance with the recent literature, our findings raise the question of whether medication monotherapy might not be the best treatment for the majority of bipolar patients, regardless of the phase they are in.13,15–22,26 The second interesting finding was that the newest atypical antipsychotic drugs, Aripiprazole and Ziprasidone, have not found any reception as treatment options in Latin America. The reasons for this are unclear. It does not seem to be a matter of cost, but rather that the experience with these medications has not been satisfactory enough to be seen as a valid option in terms of efficacy.

The third interesting finding was that there is no clear choice for the acute treatment of bipolar depression. Different treatments were chosen as first option, ranging from a mood stabilizer to an atypical antipsychotic to an antidepressant. Acute bipolar depression is probably the most challenging and difficult phase to treat, and the one that bipolar patients spend the most time in.1,27

In comparison, Lamotrigine was the first option for maintenance treatment in order to prevent a relapse of bipolar depression. The use of this medication has been on rise in the last few years, mostly in maintenance treatment in order to prevent depressive episodes in bipolar patients.28

Another finding was that almost 75% of Latin American psychiatrists will consider the use of antidepressants as part of the treatment for bipolar depression, although not usually as their first choice. The use of antidepressants in bipolar depression has also been found to be the case in the US studies as well.5,13,14,16,17,19–21 As in the previous studies the first choice of antidepressant was the SSRIs followed by Bupropion. Although they were chosen frequently, it was uncommon to be used as monotherapy.

We believe that the notion among many psychiatrists that bipolar and unipolar depressions are pretty similar and the often lack of results in treating bipolar depression with other psychotropics are the reasons behind this wide use of antidepressants. There are a few studies that suggested some benefit in the use of antidepressants in acute as well as long-term treatment of bipolar depression.29,30 However, more recent, randomized studies have been more consistent in showing that antidepressants lack efficacy in the treatment of acute bipolar depression and in preventing further depressive episodes in maintenance treatment.31–33 Nonetheless while there are a lot of therapeutics options concerning a manic state, there is a paucity of appropriate treatments for bipolar depression, and maybe one of the reasons to keep using antidepressants between our colleagues is related to that short therapeutic arsenal. There is also a lot of concern about the label ‘bipolar’, and the stigma associated, and using antidepressants seems more suitable than any other medication specially if for the patient or family there is no clear diagnosis yet. Given the current controversy regarding the efficacy of antidepressants in bipolar depression, we believe that this is a finding that should be explored further in future studies. Finally, a significant number of psychiatrists (21.5%) prescribe depot antipsychotic medication for their bipolar patients. Probably, the vast majority are typical antipsychotics, although that may change in the future with more atypical options. After analyzing the results we came to the conclusion that there are some similarities and some differences with the studies previously done in the US. The main differences are the use of polypharmacy as the initial treatment for mania and the frequent use of antidepressants for the treatment of bipolar depression.

As bipolar illness has a complex clinical presentation and some of its treatments are currently under intense debate, clinical guidelines have emerged as an important tool to bring research findings and experts opinions back to clinical practice, standardizing pharmacological treatments and recommending to avoid those psychotropic without any evidence of efficacy or even potentially harmful. However, despite supposedly being the ultimate resource for a balanced clinical practice, the different guidelines and algorithms for the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorders vary significantly across societies and expert consensus which usually constitutes the major sources for guidelines development. Although many guidelines recommend the use of monotherapy as first choice for acute bipolar mania and maintenance,34 this prescription survey demonstrated a preference for combined therapy among psychiatrists in our region. Moreover, some guidelines,35 but not all,36,37 discourage the use of AD as first line choice for bipolar depression. Besides, there is only one expert guideline for the treatment of bipolar patients in Latin America published until now,38 so the lack of a specific document prepared and adapted to the local needs, resources and characteristics could be a discouraging factor for our colleagues on their clinical practices It seems that for the most part the Latin American psychiatrists do not strictly follow the literature guidelines that are published, but rather adapt the treatment to the specific case. Although not following the published guidelines may lead to a possible ineffective or even harmful treatment, it is also true that as time passes by and new evidence is published, sometimes the guidelines become somewhat obsolete. Basing the choice of treatment in one own experience can be deceiving, so if one decides not to follow the current guidelines, you have to be up to date with the recent literature. Providing education to the Latin American psychiatrists through courses and lectures would probably be a good way of having them followed more closely the published guidelines recommendations for the treatment of bipolar disorder.

The main limitation of this study is that although eight countries were included that does not assure us that they will significantly represent all of the countries in Latin America. Also, it is very possible that the psychiatrists who answer the survey were the most informed and interested in bipolar disorders.

Some other important topics in the treatment of this illness may have not been included in the survey for reasons of space and length. The findings of this study only apply to patients with bipolar I disorder.

The reasons behind the answers and choices are of course open to interpretation and should be one of the reasons for replicating this study in Latin America as well as in other parts of the world.

ConclusionsIn general mood stabilizers were the first choice of treatment for bipolar disorder patients. Antidepressants were frequently prescribed, even in the absence of strong evidence supporting its efficacy. Polypharmacy was the rule in the majority of patients for all the phases of the disorder.

There were some similarities and a few differences with the studies previously done in the US. It seems that for the most part the Latin American psychiatrists do not strictly follow the literature guidelines that are published, but rather adapt the treatment to the specific case. More longitudinal studies of prescribing patterns in bipolar disorder are needed to corroborate these findings.

Conflicts of interestOscar Heeren, speaker's honorarium for Eli Lilly, Glaxo-SmithKline and Merck Sharp Domme laboratories.

Manuel Sánchez de Carmona, speaker's honorarium for Astra Zeneca, Glaxo-SmithKline, Pfizer, Merck Sharp Domme, Bristol Myers & Squibb and Armstrong laboratories. Advisory honorarium for Astra Zeneca, Glaxo-SmithKline, Bristol Myers & Squibb and Merck Sharp Domme laboratories.

Gustavo Vasquez, speaker's honorarium for Astra Zeneca, Glaxo-SmithKline and Eli Lilly laboratories.

Rodrigo Córdoba, speaker's honorarium for Pfizer, Merck Sharp Domme, Astra Zeneca, Janssen Cilag and Glaxo-SmithKline laboratories. Advisory honorarium for Pfizer and Merck Sharp Domme.

Jorge Forero, speaker's honorarium for Glaxo-SmithKline and Roche laboratories. Advisory honorarium for Glaxo-SmithKline and Roche laboratories.

Luis Madrid, speaker's honorarium for Eli Lilly, Abbott, Glaxo-SmithKline, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp Domme, Bristol Myers & Squibb and Lundbeck laboratories. Advisory honorarium for Eli Lilly, Abbott and Glaxo-SmithKline laboratories.

Diogo Lara, speaker's honorarium for Astra Zeneca, Abbott, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Glaxo-SmithKline laboratories. Advisory honorarium for Astra Zeneca and Abbott laboratories.

Rafael Medina, speaker's honorarium for Astra Zeneca and Janssen Cilag laboratories.

Luisa Meza has no interest to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Heeren O, et al. Tratamiento psicofarmacológico del trastorno bipolar en América Latina. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2011;4:205–11.