Although it is widely known that prolactin levels increase in schizophrenia patients treated with antipsychotic drugs,1 the exact role of this hormone during the course of the disease is not fully understood. Recent studies in this field are consistent with an increase in prolactin levels and even a higher prevalence of hyperprolactinemia among drug-naïve subjects with a first episode psychosis (FEP).2,3 Although some studies suggest that prolactin levels might predict the risk of developing a psychotic disorder in UHR individuals,4 other studies have not found such association.5 Some studies have shown a negative correlation between prolactin levels and disease severity6,7 as well as with cognitive deficits.8 Our group has previously shown a negative correlation between prolactin levels and positive symptoms’ severity in women with FEP.3 This, together with evidence in animal models of stress,9 suggests that prolactin might have a neuroprotective role during FEP. We, therefore, hypothesize that an increase in prolactin in patients with FEP may have a neuroprotective role. A prospective study of the response to treatment in a cohort of FEP patients has been undertaken.

Data for this study were obtained from a large clinical intervention program of FEP (Programa Asistencial Fases Iniciales de Psicosis [PAFIP]), conducted at the University Hospital Marques de Valdecilla (Santander, Spain), whose detailed methodology is described elsewhere.10 All subjects provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee. This study was conducted as part of a clinical trial “Longitudinal Long-term Study (10 years) of the Sample of First Episode of Non-affective Psychosis: PAFIP (10PAFIP)” (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02200588). Selected cases included those with available data regarding basal and prolactin at 10 year and clinical data at 10 years. This allowed for calculating the remission, the response, the duration of active psychotic symptoms after commencing treatment (DAT), the duration of active psychotic symptoms (DAP), and the chlorpromazine accumulated equivalent dose (CAED) at 10 years. Remission was defined as a score in the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and in the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)≤2 and the absence of relapses in the preceding 6 months to the evaluation.11 Response was considered when the Brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS) was reduced at least 40% from baseline and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) was ≤4. The DAT was calculated as the time of active psychosis after antipsychotic treatment onset and during subsequent relapses, if present, whereas the DAP was calculated adding the Duration of Untreated Psychosis (DUP) to the DAT. The CAED was estimated according to Gardner et al. (2010).12 Given that patients included in PAFIP program could have been treated with antipsychotic for less than six weeks, only those patients that had not received any antipsychotic treatment prior to the day of prolactin assessment were selected. Patients with levels of prolactin above 100ng/mL were excluded, as such a high prolactin levels might be related to other somatic disorders or to unreported antipsychotic exposure.

Fort the comparison of prolactin levels before treatment with the levels at 10 years, the Wilcoxon test was used. In order to determine whether there was any association between prolactin basal levels and the DAT or DAP the Spearman correlation test was used. And in order to assess whether the levels of prolactin before the onset of treatment were predictors of the remission or the response, logistic regression models were used with the later as the dependent variables and basal prolactin as the independent variable. The CAED, sex and age were used as co-variables.

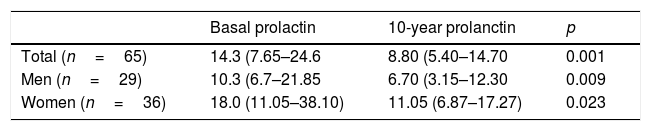

Sixty-five patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Prolactin levels significantly decreased at the end of the follow-up period, with a median and interquartile range at the beginning of 14.3 (7.6–24.6) ng/mL and at the end of 8.8 (5.4–14.7) ng/mL (p=0.001) (Table 1). There were no significant correlation between basal prolactin levels and the DAT (p=0.715) or the DAP (p=0.332). The logistic regression model showed a significant association between basal prolactin and remission (p=0.047) when the CAED was introduced as a co-variable (being this also significant [p=0.003]), which did not survive when introducing age and sex as well (p=0.244). There were not significant associations with response (p=0.257) at 10 years follow-up.

According to our results there is no evidence to support any association between the levels of prolactin before the onset of treatment in patients with FEP and their clinical evolution or the response to treatment at 10 years follow-up. The small final sample size, inherent in such a long study, may have influenced the lack of statistical significance when introducing potential confounding co-variables. Nevertheless, we consider it might be worth continuing to explore this hypothesis in larger samples or evaluating other outcome variables, such as neuroimaging.

Funding sourcesThis study received no specific funding.

Conflict of interestAuthors do not have any conflict of interest.