Mental health services are not systematically involved in the care of dementias in Spain. Nevertheless, many patients with dementia attend these services. The perspective of psychiatrist as regards this situation has not been evaluated at the national level to date, and it may be of interest to determine their actual involvement and the strategies to foster it.

Material and methodsA survey was conducted on 2000 psychiatrists on a range of mental health care services. Respondents provided socio-demographic data and information about clinical aspects, together with their opinions regarding the management of dementia. Responses were described by their raw frequencies and measures of association for cross-tabulations resulting from selected pairs of questions. Inferences were made by calculating their 95% confidence intervals.

ResultsPsychiatrist involvement in the management of dementias was limited, aside from those involved in psycho-geriatric units or nursing homes facilities. However, there were wide, regional differences. Nearly all respondents (81%) were ready to augment their knowledge and skills in the area of dementia. In particular, the insufficient medical education, together with other organisational factors, such as the difficulties in ordering diagnostic tests (i.e. neuroimaging), or prescribing anti-dementia drugs in some regions, were common barriers psychiatrists faced when approaching patients with dementia.

ConclusionsIncreasing psychiatrist involvement and boosting coordinated efforts with other specialists in a form of integrated care may advance the care of dementias in Spain to a more valuable level.

Aunque los recursos sanitarios empleados en la atención de las demencias en España no incluyen sistemáticamente a los servicios de salud mental, muchos de los pacientes atendidos en ellos sufren demencia. La perspectiva de los psiquiatras al respecto, no evaluada a nivel nacional hasta la fecha, es de interés para conocer su implicación real e identificar estrategias para aumentarla.

Material y métodosSe realizó una encuesta a una muestra de 2.000 psiquiatras con actividad en diferentes ámbitos asistenciales. Se recogieron datos sociodemográficos de los encuestados y sobre aspectos clínicos y opiniones relativos al abordaje de las demencias. Se calcularon las frecuencias de cada opción de respuesta y medidas de asociación para las frecuencias cruzadas entre pares de preguntas de interés, junto con sus intervalos de confianza del 95%.

ResultadosSalvo en unidades de psicogeriatría y centros de larga estancia, la participación de los psiquiatras en la atención de las demencias es limitada. No obstante, se observaron diferencias importantes entre comunidades autónomas. Casi todos los encuestados (81%) se mostraron dispuestos a ampliar sus conocimientos en el área de las demencias. Precisamente la falta de formación, junto con otros factores de tipo organizativo como el difícil acceso a pruebas complementarias (por ejemplo, técnicas de neuroimagen) o la prescripción de fármacos antidemencia fueron dificultades comúnmente citadas para el abordaje de los pacientes con demencia.

ConclusionesEl incremento de la implicación de los psiquiatras y su coordinación con otros especialistas para proporcionar cuidados integrados son aspectos mejorables de la atención sanitaria de las demencias en España.

Frequent psychiatric comorbidities are vastly responsible for the suffering of patients and caregivers caused by clinical dementia syndromes.1 Unlike the traditional view that integrated the psychopathological (psychological and behavioural) symptoms in the psychological reaction with the neurological symptoms from brain pathologies, the evidence currently indicates that the brain disease itself is the direct cause of such symptoms.2,3 The growing epidemiological significance of chronic brain diseases—including degenerative conditions and, notably, Alzheimer's disease; the onset of psychopathological manifestations in the course of the disease of almost every patient4–6 and their consequences on their health-related quality of life1; the frequency of institutionalisations7 and the burden for caregivers8 justify involving a psychiatrist in the health care of dementia.9–11 Moreover, Alzheimer's disease implies a constellation of social and health care issues, such as the assessment of caregiver overload and patient competencies, or the use of community resources, for the management of which a psychiatrist is especially qualified.12

Unlike the usual situation in other countries, clinical psychiatrists are little involved in the care of dementia in Spain. A priori, this may be understood as a lack of strategic health care planning, characterised by the separation of the network of mental health services from the orbit where dementia is usually seen.13 Nevertheless, there is no available information collected in a homogeneous manner at the national level about the clinical psychiatrists’ perspective in this regard.

This article reports the results of a survey conducted among practicing psychiatrists in Spain. The goals of the survey were: (a) to get to know the actual degree of involvement of psychiatrists in the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of dementia at present, and the difficulties perceived for their approach, and (b) to identify the educational needs of psychiatrists in this field. With this article, the authors also expect to foster the interest of psychiatrists in dementia and their involvement in the approach to dementia as well as to stimulate the joint work of psychiatrists with other specialists—particularly family doctors, neurologists and geriatricians—which would result in an improvement of health care quality.

Material and methodsSampleThe source population of this research is made up of the set of practicing psychiatrists in Spain, approximately 5000 psychiatrists. A non-probability quota sampling technique was used for psychiatrists actively working in different health care settings within the general psychiatry practice for adult patients and who were available for the visit. The number of psychiatrists invited to participate in each province (sampling quota) was proportional to the density of psychiatrists practicing in that province.

Data collection techniqueA self-administered, structured questionnaire with 25 questions was used. The questionnaire structure was as follows: the first six questions were related to sociodemographic data and the scope of the respondents’ clinical practice, two questions referred to the number of patients with dementia in their practice, two further questions dealt with the respondent's educational level and current knowledge about the diagnosis and treatment of dementia, four were related to the psychiatrist's opinion and role with respect to the approach to dementia, one question had to do with the use of clinical assessment tools, three questions were about the use of specific anti-dementia drugs and the remaining seven questions dealt with perceived needs of education in the field of dementia. Except for the respondent's age, all the remaining questions were provided with closed-ended options, even though in some cases there was an option to collect additional answers, together with an open-text field for further specifications. In seven questions, more than one option could be provided as an answer.

Statistical considerationsA decision was made to set a minimum sample size of 1000 respondents to have a precision of at least ±2.8% in order to estimate a 50% proportion in a finite population of 5000 individuals with a two-sided 95% confidence interval. A conservative degree of response (participation) was assumed, from 50% of respondents, so the recruitment goal was set at 2000 psychiatrists.

A descriptive analysis of the data was carried out in the form of absolute and relative frequencies. Multi-level contingency tables were conducted to calculate the crossed frequencies of answers between pairs of questions of interest. For ordered response options (for example, age ranges or educational level), the differences and the linear trends between the resulting stratified frequencies were analysed by means of two-sided tests based on statistical chi-square test for linear trend and by simple linear regression of the absolute frequencies to obtain a measurement of the association extent. For the relationship between two questions with non-ordered response options (for example, type of workplace or training format), crude odds ratios were calculated among the response categories. Additionally, the two-sided 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for relative frequencies and association measures of interest (regression coefficients [B] and odds ratios). All these analyses were conducted with the SPSS statistics package for Windows, version 18. Additionally, the answers in the category “Other” with an open-text field to provide further specifications were analysed with the IBM Text Analysis for Surveys (Spanish edition, version 3.5) application.

ResultsSurvey acceptance and sociodemographic data of respondentsThe survey was returned by 1248 respondents (62% of 2000); out of them, 1110 (55%) filled the questionnaire in its entirety. One hundred fifteen respondents left one question unanswered and the remaining 23 respondents left more than one question unanswered. The most frequently skipped data were the autonomous community and the age, followed by the availability to expand dementia-related education, the years of experience and the setting of professional practice. Relative frequencies have been calculated with respect to the total number of respondents who answered each question, including those that allowed multiple answers.

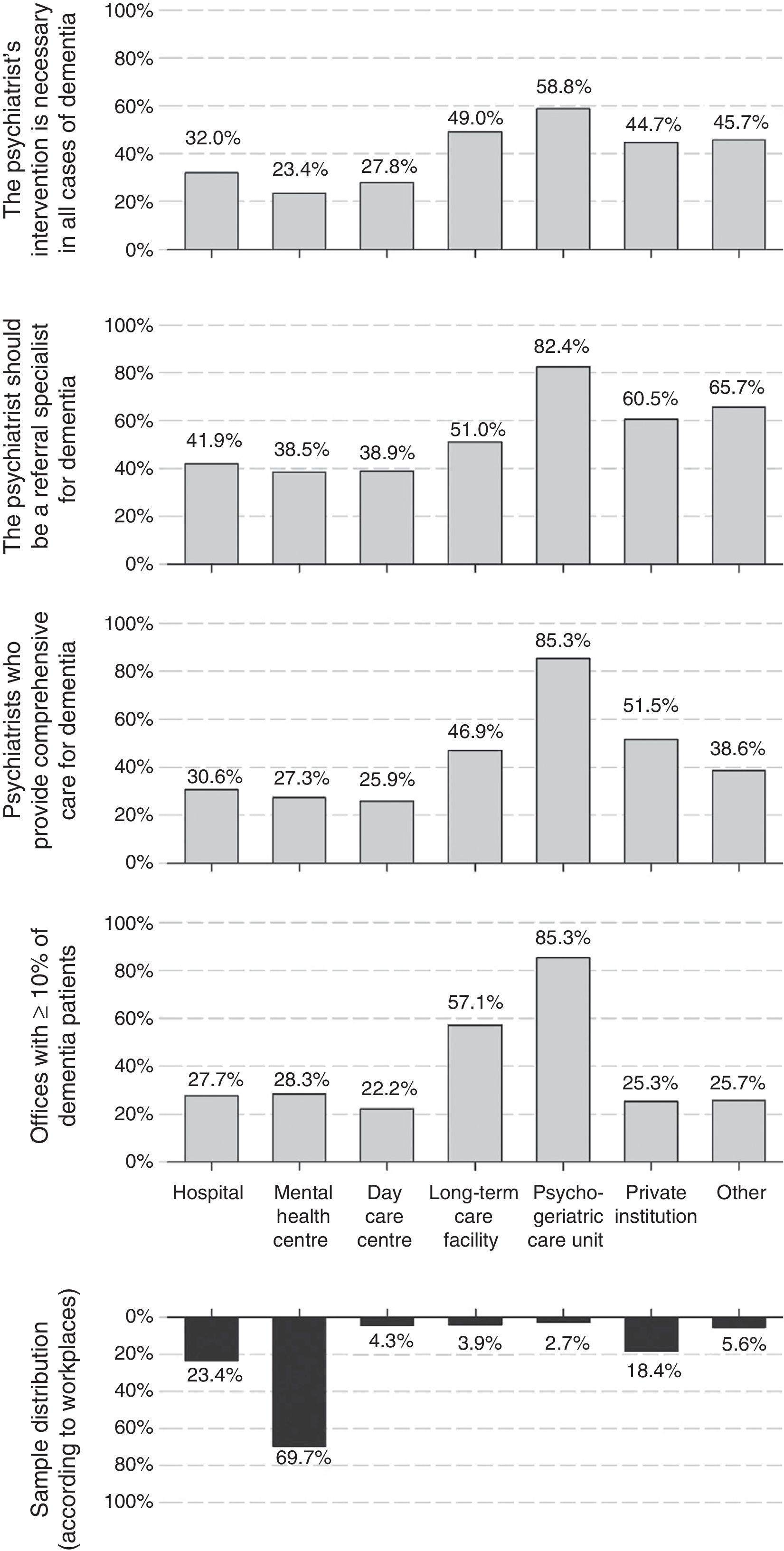

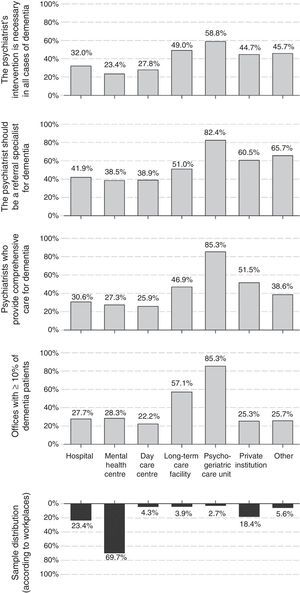

Fifty-three percent of psychiatrists were men; mean age (standard deviation [SD]) in the sample of respondents was 46.1 (9.5) years and the average experience was 18.7 (9.8) years of professional practice. Both age and years of professional practice were lower in female than male respondents. The most common workplaces were mental health centres, psychiatric hospitalisation units and private institutions (Fig. 1); 30% of respondents checked more than one workplace. Seventy-three percent of them worked exclusively in the public sector, and only 4% worked exclusively in the private sector; the remaining 23% worked in both spheres.

Proportion of dementia patients who receive careThe proportion of patients aged 65 years and older was significant at the respondents’ offices. While 41% considered that this percentage is lower than 20%, 42% of psychiatrists placed it between 20% and 40% and for 12% of respondents this category was even greater, between 40% and 60%. Up to 28% of the psychiatrists indicated that dementia patients account for, at least, 10% of the patients seen at their office. The workplaces with the highest proportion of dementia patients were the psychogeriatric care units and long-term care facilities, where only 3% and 4% of the respondents worked, respectively. The proportion of patients with dementia did not vary based on respondents’ age (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: −0.03 [−0.07; 0.01], linear chi-square p-value [pχ(tl)]: 0.119), but it was lower among male psychiatrists (B [95% CI] for men versus women: −0.09 [−0.17; −0.01], pχ(tl): 0.037). It was also substantially higher at the psychogeriatric care units and long-term care facilities (Fig. 1).

Current educational levelAround half of psychiatrists considered that their knowledge regarding the diagnosis (54%) and treatment (48%) of dementia was acceptable, even though less than a fourth considered such knowledge as good or very good (21% and 23%, respectively). The educational level for the diagnosis increased slightly but significantly with the respondents’ age (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: 0.06 [0.02; 0.10], pχ(tl): 0.008), and was slightly higher among male than female psychiatrists (B [95% CI] for men versus women: 0.22 [0.14; 0.31], pχ(tl): <0.001). The educational level for the treatment of dementia did not vary significantly among the respondents’ age groups (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: 0.04 [−0.01; 0.09], pχ(tl): 0.085), but it was also higher among men than among women (B [95% CI] for men versus women: 0.22 [0.13–0.31], pχ(tl): <0.001). As expected, differences were also registered at the educational level reported according to the workplaces—these levels were higher for psychiatrists working at a long-term care facility (OR [95% CI] versus those who worked at mental health centres: 3.89 [2.16; 7.02] for diagnosis; 4.92 [2.74; 8.84] for treatment) or at a psychogeriatric care unit (OR [95% CI] versus mental health centres: 22.31 [9.08; 54.82] for diagnosis; 14.14 [6.29; 31.81] for treatment). The psychiatrists who worked at mental health centres (70% of the sample) were the ones who reported having good or very good knowledge less often (OR [95% CI] versus the total of all the other workplaces: 0.48 [0.38; 0.61] for diagnosis and 0.11 [0.09; 0.14] for treatment).

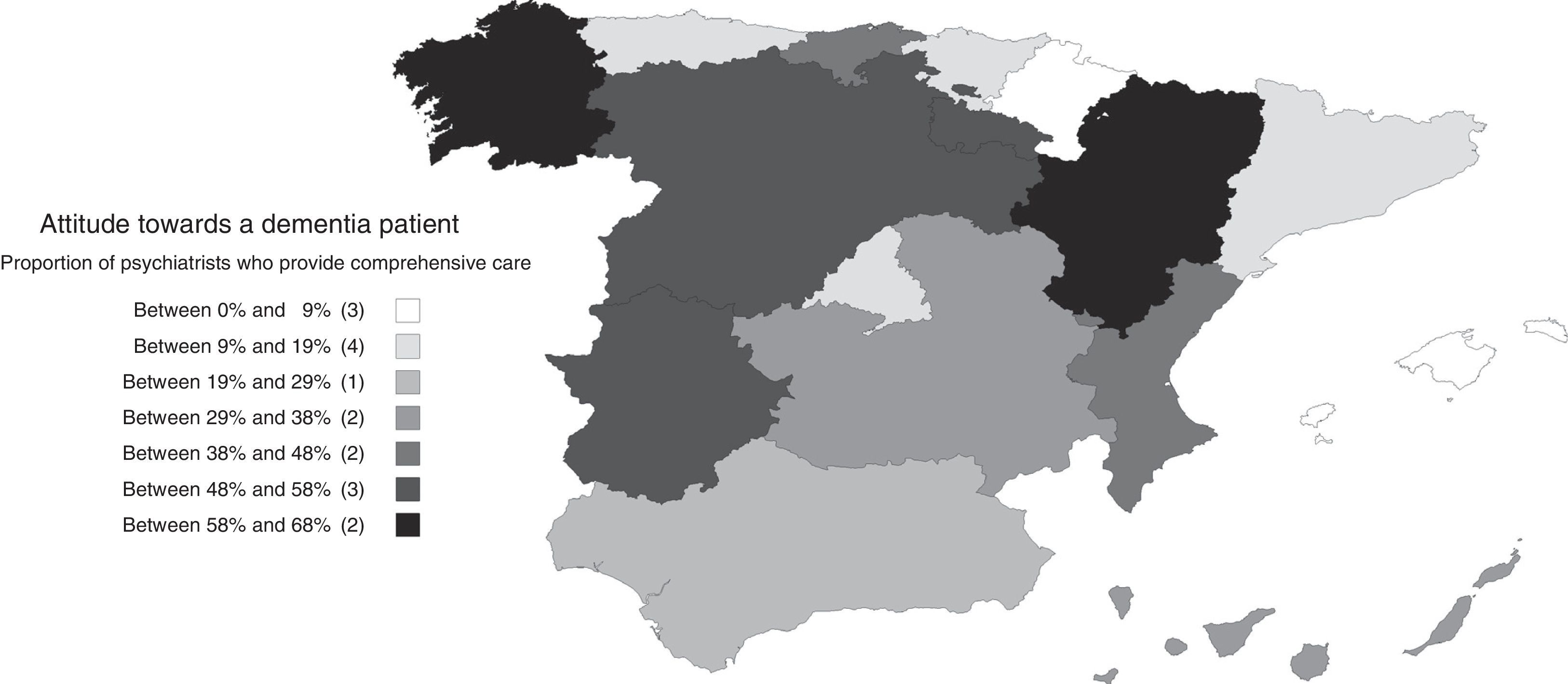

Psychiatrists’ attitudes and opinions regarding dementiaThirty percent of psychiatrists stated that they were in charge of the diagnosis, follow-up and treatment of dementia (comprehensive care), and 34% indicated that they were only in charge of treatment and follow-up of neuropsychiatric symptoms, leaving the diagnosis and treatment of cognitive symptoms in the hands of another specialist. Thirty percent of the psychiatrists report that they refer dementia patients to other specialists. Comprehensive care was more common at the psychogeriatric care units, private institutions and long-term care facilities than in mental health centres (Fig. 1). This attitude did not show a significant association with the respondents’ age (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: −0.04 [−0.10; 0.10], pχ(tl): 0.116), although male psychiatrists had a comprehensive care-oriented attitude more frequently than female psychiatrists (B [95% CI] for men versus women: 0.14 [0.04; 0.24], pχ(tl): 0.007). Differences in these attitudes were also noted by autonomous communities (Fig. 2), with comprehensive care being very limited in some communities, such as the Balearic Islands (4%), Navarre (5%), Catalonia (9%), Asturias (10%) or Madrid (12%), but very common in others, such as Aragon (68%), Galicia (63%) or Castile and León (58%).

The low proportion of patients with dementia who receive care is not concordant with the psychiatrists’ opinion about what their role should be with those patients: 40% consider that it should be one of the referral specialists and 30% consider that they should cooperate with other specialists on a regular basis. The distribution of the answers with respect to the workplace, age and gender was similar to the distribution seen in the previous paragraph about attitudes. That is to say, the opinion favouring greater involvement was more common in psychogeriatric care units, private institutions and long-term care facilities than in mental health centres (Fig. 1); it was also higher among male than female psychiatrists (B [95% CI] for men versus women: 0.11 [0.01; 0.21], pχ(tl): 0.007).

Moreover, most psychiatrists consider that their intervention is necessary in dementia cases: 28% consider that it should be that way in all cases and 49% think that their intervention is necessary in many patients. As with previous issues, the proportion of psychiatrists working at psychogeriatric care units or long-term care facilities who considered that their intervention is necessary in all cases of dementia was higher than at mental health centres (Fig. 1). The opinion about the role of the psychiatrist did not vary based on the respondents’ age (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: 0.00 [−0.04; 0.04], pχ(tl): 0.956), but more male than female psychiatrists considered that their intervention was necessary (B [95% CI] for men versus women: 0.10 [0.02; 0.18], pχ(tl): 0.012).

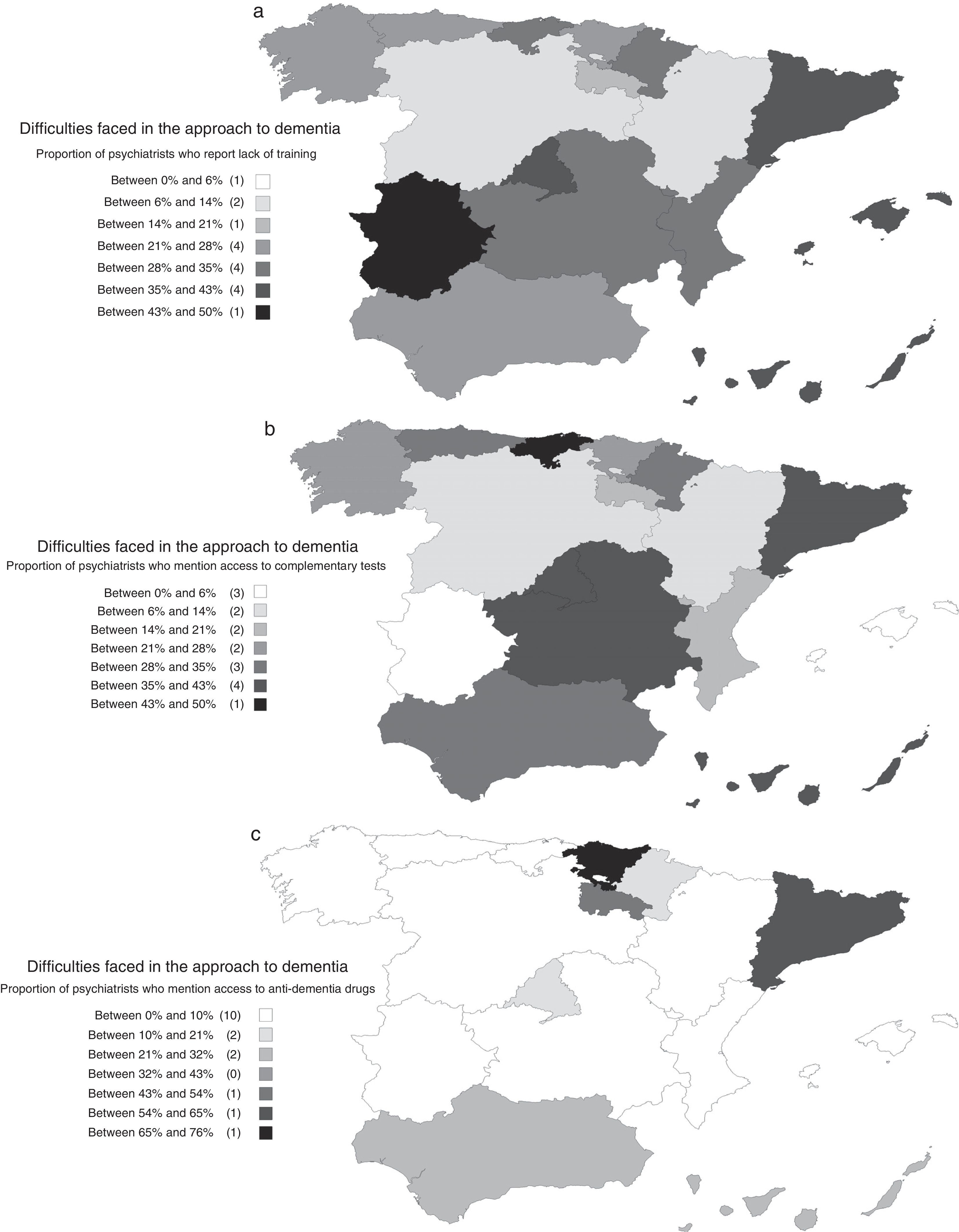

Difficulties in the approach to dementiaGiven that these opinions are not consistent with the low proportion of cases under the care of psychiatrists, the answers to questions dealing with the difficulties in the approach to dementia patients are of interest. Even though 38% of respondents replied that they do not encounter any difficulties, 31% admitted having difficulties with access to complementary tests and 30% indicated lack of experience or training. It is also relevant that 23% answered that they found difficulties prescribing anti-dementia drugs. More than one option was checked by 32% of respondents.

The detected difficulties varied depending on the workplace and the psychiatrists’ educational level. They were lower among psychiatrists practising at psychogeriatric care units; the OR (95% CI) of absence of difficulties in psychogeriatric care units versus the total of all the other workplaces was 2.11 (1.06; 4.20). Overall, the barriers perceived were lower among psychiatrists with higher educational levels. The OR (95% CI) of absence of difficulties among psychiatrists with good or very good knowledge versus psychiatrists with acceptable or lower-than-acceptable knowledge for the diagnosis of dementia was 2.26 (1.72; 2.98). This OR (95% CI) corresponding to the knowledge required for treatment was 2.74 (2.09; 3.60). The differences among the many autonomous communities are also interesting, with the presence of difficulties being lower precisely in those regions where the comprehensive care of dementia was more common (Fig. 3).

(a) Distribution, by autonomous communities, of the difficulties faced in the approach to dementia: proportion of psychiatrists who report lack of training. (b) Distribution, by autonomous community, of the difficulties faced in the approach to dementia: proportion of psychiatrists who report difficulties with access to complementary tests. (c) Distribution, by autonomous communities, of the difficulties faced in the approach to dementia: proportion of psychiatrists who report difficulties having access to anti-dementia drugs.

In line with the data explained above, and despite the relatively small number of cases under the care of psychiatrists, 39% of them answered that they sometimes use a clinical instrument for the assessment of dementia and 24% stated that they use them routinely. No differences in use were observed based on the respondents’ age (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: 0.02 [−0.03; 0.07], pχ(tl): 0.355), but their use was more common among male than female psychiatrists (B [95% CI] for men versus women: 0.17 [0.08; 0.27], pχ(tl): <0.001).

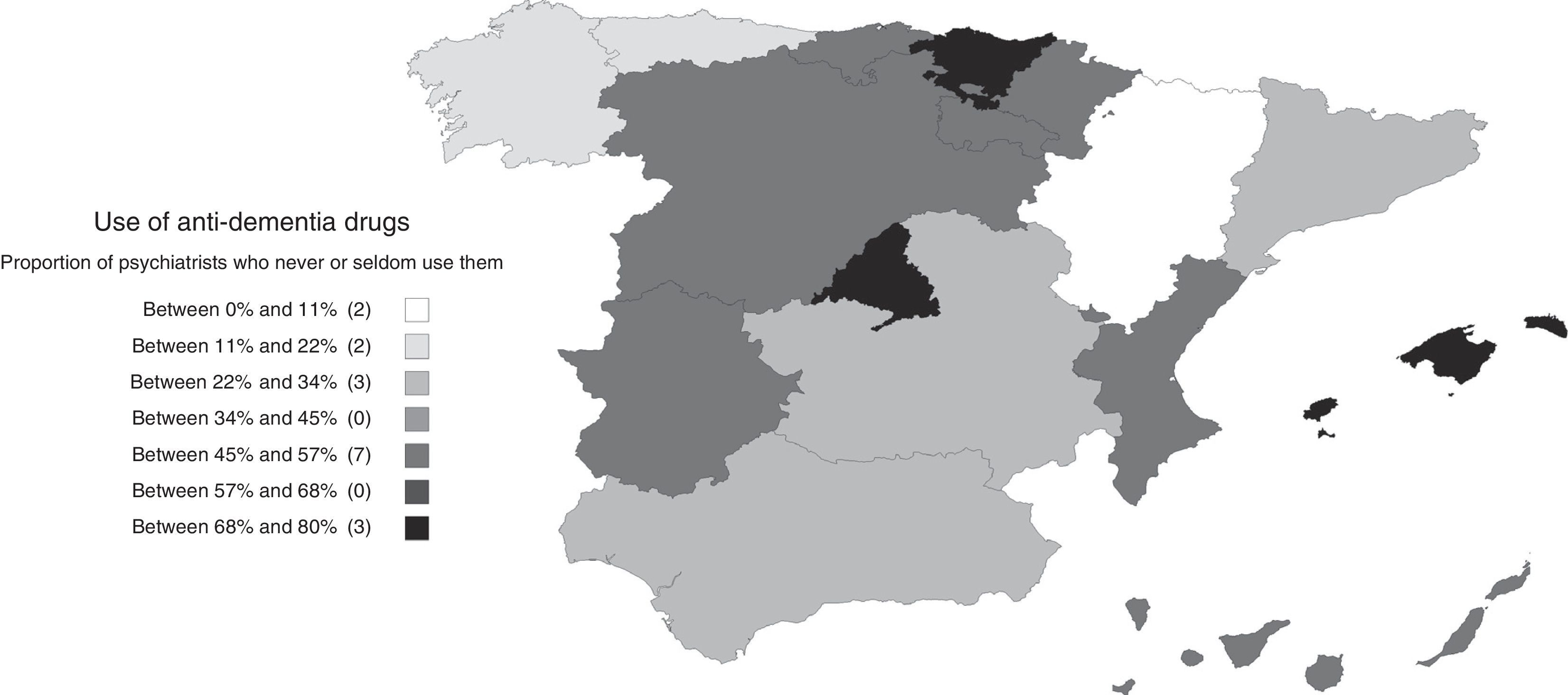

Use and opinions regarding anti-dementia drugsTwenty-five percent reported that they use anti-dementia drugs often, along with 28% who declared using them occasionally; the remaining 46% answered that they seldom or never used them. The proportion of psychiatrists who use anti-dementia drugs varied in the different autonomous communities, being less frequent in the Community of Madrid, the Basque Country and the Balearic Islands (Fig. 4). Among the ones who answered that they did not use them on a regular basis (sometimes, seldom or never), the most common reasons provided were lack of experience with their use (49%), the complexity of the bureaucratic procedures (28%) and the lack of access to the prescription (18%). Only 6% indicated lack of efficacy as the reason. Twenty percent of the respondents indicated more than one reason.

Most psychiatrists did not have an unfavourable opinion about the use of anti-dementia drugs: 51% considered that their usefulness is acceptable and 12% indicated that they are very useful. Twenty-five percent considered them somewhat useful, and the far from negligible figure of 10% reported not having a fully developed opinion. It is interesting that up to 40% of psychiatrists considered that in a mid-term future their involvement in the treatment of dementia patients will increase. Nevertheless, 40% considered that it will remain the same.

Education in the field of dementiaFifty-eight percent of the 1248 respondents indicated having received some type of education in the field of dementia over the last year. For many of them (73%, accounting for 45% of the entire sample) it was through talks, conferences or lectures. Up to 34% of the psychiatrists who received education (20% of the entire sample) did so by means of courses. It is very relevant that up to 81% expressed to be willing to further their education on dementia, a proportion that decreased significantly as the respondents’ age increased (B [95% CI] for increasing age ranges: −0.05 [−0.08, −0.03], pχ(tl): <0.001) but it did not differ by gender (B [95% CI] for men versus women: −0.02 [−0.06; 0.03], pχ(tl): 0.451). Of them, 44% declared that they would attend in-person training; 36% would rather get web-based learning. Most of them declared to be willing to receive different format types, such as courses (61%), discussion of clinical cases (58%) and workshops (53%). The monographic exhibition format received less support (31%). As a sign of interest in receiving education on this issue, up to 50% of respondents indicated that they would attend monthly meetings versus 26% who preferred having a single session. Only 7% stated that they would attend weekly sessions. Quarterly sessions (6% of psychiatrists willing to receive education) or biannual sessions (5%) were also proposed (aside from the others). Most respondents (58% of psychiatrists willing to receive education) preferred having short sessions, of up to 2h, versus a smaller proportion of respondents (35%) whose opinion was that sessions should last between 2 and 5h. The respondents showed interest in the many educational aspects proposed; the most frequently reported ones were: pharmacological therapy (82% of psychiatrists willing to receive education), differential diagnosis (78%), overall diagnostic methodology (60%) and psychopathology of dementia (58%). The remaining options were also checked by a substantial proportion of respondents: psychometric instruments (49%), non-pharmacological treatment and caregiver overload (47% each). On average, each psychiatrist selected more than four educational aspects of interest.

DiscussionThe survey acceptance was good and therefore the authors consider that it may be deemed representative of psychiatrists’ perspective regarding the health care of dementia in Spain (it has external validity). The results indicate that, except for the small number of psychiatrists working at psychogeriatric care units or long-term care facilities, the involvement of psychiatrists in the approach to dementia is low, although not negligible, in Spain. It is particularly so if we consider that the psychiatrist's intervention is addressed to the most complex cases, such as those with prominent psychological or behavioural symptoms, with psychiatric diagnoses or cases with a severely disturbed family dynamic. Consistently, in a recent study conducted with competitive recruitment in Spain about the management of incident cases by specialised physicians, most patients (64.7%) were recruited by neurologists (versus 21.9% by psychiatrists).14 Despite that fact, the majority of the surveyed psychiatrists answered that they had an acceptable educational level for the diagnosis and treatment of dementia and, as already indicated by other surveys,15 a good disposition to improve it. Moreover, they declared that they should have a more prominent role in the management of these pathologies, but pointed out challenges for attaining that.

The growing age of the population may be associated with an increase in the prevalence of dementia. It has been estimated that Alzheimer's disease alone is already causing greater disability than diabetes in Europe.16 This is, therefore, a major public health problem that should be approached effectively.17

Considering that psychopathological symptoms are associated with greater morbidity and functional impairment than cognitive symptoms,7,8 it is reasonable to argue that a greater involvement by psychiatrists could benefit the health care of dementia in Spain. For such purpose, it would be important to enhance their training in psychogeriatrics.18 In addition to playing a more central role, it has been pointed out that there should be good coordination between psychiatrists and other specialists—in particular, family doctors, neurologists and geriatricians—to provide patients with the best care possible.19 For example, whereas neurologists carry out an appropriate examination including diagnostic tests directed to identify a brain disease, psychiatrists pay more attention to the psychopathological symptoms and have better knowledge of the resources to contain the personal and social impact of dementia.20 The fact that a greater involvement of psychiatrists in addition to a good coordination with neurologists could improve the care of dementia in Spain is supported by the results of the study of incident cases mentioned above, which was focused on neurologists and made it evident that psychopathological symptoms generally receive less attention than cognitive symptoms14; this fact has also been reflected in a critical review of the Spanish health care system situation with respect to the management of dementia.13 The latter circumstance is in disagreement with the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) recommendations for the management of Alzheimer's disease, in which equal importance is given to both type of symptoms.16

The differences in several aspects found among the autonomous communities reveal a heterogeneous landscape where the influences of the setting have a significant impact on psychiatrists’ involvement in the approach to dementia. In particular, one of the most relevant aspects in the clinical practice—the use of anti-dementia drugs—proved to be interwoven with several differential circumstances among regions, which make health care complicated in this area. Thus, the significant differences seen in the prescription of anti-dementia drugs could be due to the difficulties caused by the lack of training rather than the access to prescriptions—although the Basque Country displays a unique situation because these drugs are not available to psychiatrists. For example, in Catalonia, most respondents indicated that one of the challenges to the approach to dementia is the difficulty of having access to the prescription of anti-dementia drugs; yet Catalonia is not listed among the communities where anti-dementia drugs are least prescribed. On the other hand, in the Community of Madrid, only a small proportion of psychiatrists indicated having difficulties of access to the prescription of anti-dementia drugs, despite it being one of the autonomous communities where they are less used. In addition to the difficulties of prescribing these drugs, other factors seem to have a great influence on psychiatrists’ involvement, such as the lack of training and the difficulties of access to complementary tests, as well as challenges related to organisational factors, as indicated by the low proportion of psychiatrists that provide comprehensive care for dementia in the Community of Madrid. These regional differences reflect the lack of a nationwide strategy for the detection, diagnosis and treatment of dementia that integrates mental health centres. This translates into a relative lack of care of psychopathological symptoms and the inappropriate use of the social services available.13,21

The good results obtained at the psychogeriatric care units, where the psychiatrists’ involvement was much higher and the difficulties of addressing dementia were fewer, may be indicative of the direction to take, as it has already been suggested in other countries,22 in an attempt to assimilate the integrated-care model used in those units into the psychiatry outpatient offices, the workplace for most of the surveyed psychiatrists.

The sampling technique used is a limitation of this paper. Only psychiatrists available for visits could be selected to participate, so the opinions of those not meeting this criterion are not represented. The sampling quotas were established based on the density of psychiatrists actively employed in each province and not based on the workplaces, so the representation of the different workplaces may not reflect their relative importance within the entire health care system. These sampling issues could explain some paradoxical results, such as the low proportion of psychiatrists who provide comprehensive care in Catalonia, despite the significant development of integrated services for the social and health care of dementia in that Community. The analyses performed on the data have an exploratory value only. In order to confirm some of the findings, it would be necessary to establish an a priori hypothesis and design a study with sufficient statistical power to prove it.

In conclusion, the involvement of psychiatrists in the health care of dementia in Spain is low and less than that existing in other countries of the region. Furthermore, major organisational differences have been verified among the autonomous communities affecting the participation of psychiatrists. The European guidelines for the approach to dementia recommend the collaboration of neurologists and psychiatrists to achieve suitable care for the constellation of manifestations and consequences of these conditions. At the same time, some previous works conducted in Spain have indicated that the level of treatment of psychopathological symptoms and the level of coordination of social resources are lower than the ones attained in other areas, such as the management of cognitive symptoms. Increasing psychiatrists’ involvement could be translated into improvements in the health care of dementia in Spain. The integrated-care model employed at the psychogeriatric care units could be used for that purpose.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments have been conducted in humans or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that this paper does not contain patient-related data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this article does not contain patient-related data.

FundingThis investigation has been funded by Esteve.

Conflicts of interestManuel Martín-Carrasco has been a lecturer in medical education activities for Pfizer, Janssen, Novartis, Lündbeck, Servier and Esteve, and has received unrestricted research grants from Novartis and Pfizer.

Javier Arranz is a full-time employee at Esteve.

The questionnaire for this study has received Scientific Support from the Sociedad Española de Psicogeriatría (SEPG) [Spanish Society of Psychogeriatrics]. The responsibility for the study performance and for the interpretation of the results corresponds to the study authors exclusively. The authors thank Jesús Villoria (medical writer, Medicxact, S.L.) for his work in the preparation of this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Carrasco M, Arranz FJ. Perspectiva de los psiquiatras españoles respecto a la atención de las demencias. La encuesta PsicoDem. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2015;8:17–25.