Few controlled trials have assessed the impact of Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) on symptoms and functioning in bipolar disorder (BD). This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of MBCT adjunctive group treatment.

Material and methodsRandomized, prospective, multicenter, single-blinded trial that included BP-outpatients with subthreshold depressive symptoms. Participants were randomly assigned to three arms: treatment as usual (TAU); TAU plus psychoeducation; and TAU plus MBCT. Primary outcome was change in Hamilton-D score; secondary endpoints were change in anxiety, hypo/mania symptoms and functional improvement. Patients were assessed at baseline (V1), 8 weeks (V2) and 6 months (V3). Main hypothesis was that adjunctive MBCT would improve depressive symptoms more than psychoeducation.

ResultsEighty-four participants were recruited (MBCT=40, Psychoeducation=34, TAU=10). Depressive symptoms improved in the three arms between V1 and V2 (p<0.0001), and between V1 and V3 (p<0.0001), and did not change between V2 and V3. At V3 no significant differences between groups were found. There were no significant differences in other measures either.

ConclusionsIn our BD population we did not find superiority of adjunctive MBCT over adjunctive Psychoeducation or TAU on subsyndromal depressive symptoms; neither on anxiety, hypo/mania, relapses, or functioning.

Pocos ensayos controlados han evaluado el impacto de la terapia cognitiva basada en mindfulness (MBCT) en síntomas y funcionamiento del trastorno bipolar (TB). Este estudio pretende evaluar la eficacia del tratamiento grupal de la MBCT.

Material y métodosEnsayo aleatorizado, prospectivo, multicéntrico, con ciego simple, en pacientes ambulatorios con TB con síntomas depresivos subumbrales. Los participantes fueron aleatorizados en 3 ramas: tratamiento habitual (TAU), TAU más psicoeducación y TAU más MBCT. El resultado principal fue el cambio en la puntuación de Hamilton-D. Las medidas secundarias fueron los cambios en ansiedad, hipo/manía y funcionamiento. Los pacientes fueron evaluados al inicio (V1), 8 semanas (V2) y 6 meses (V3) después. La hipótesis principal fue que el tratamiento con MBCT adyuvante mejoraría los síntomas depresivos más que la psicoeducación.

ResultadosOchenta y cuatro participantes fueron reclutados (MBCT=40, psicoeducación=34 y TAU=10). Los síntomas depresivos mejoraron en las 3 ramas entre V1 y V2 (p<0,0001), y entre V1 y V3 (p<0,0001), sin cambios entre V2 y V3. En V3 no se encontraron diferencias significativas entre grupos. Tampoco hubo diferencias significativas en las otras medidas.

ConclusionesEn nuestra población con TB no encontramos superioridad de la MBCT sobre psicoeducación o TAU en síntomas depresivos subsindrómicos, ansiedad, hipo/manía, recaídas o funcionamiento.

Bipolar disorders (BD) are chronic disorders characterized by cyclic depressive and hypo/manic episodes. Lifetime prevalence is 2.4% worldwide, and they are considered one of the main causes of disability.1 Adequate pharmacological treatment is crucial.2 However, even in patients with adequate pharmacological adherence, BD patients present frequent recurrent episodes and subsyndromal depressive symptoms between episodes.3,4 These subthreshold symptoms have been related to an increased risk of affective relapses,5 worsening of psychosocial functioning,6 poorer quality of life,7 difficulties in emotional regulation8 and cognitive and social cognitive deficit.9 Adjunctive psychosocial interventions to pharmacological therapy can improve outcome, well-being and functioning of BD patients.10 Although no specific intervention has shown clear evidence of efficacy on subsyndromal depressive symptoms, they are recommended in clinical Guidelines (NICE).

Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)11 has shown efficacy in the management of major unipolar depression, not only in relapse prevention12–14 but also in improving acute depressive symptoms15 and subthreshold depressive symptoms.16

In bipolar disorder, MBCT could be beneficial in regulating emotions, diminishing rumination, worry, and non-acceptance and increasing reappraisal capacity.17,18 Although it seems to have a positive effect on anxiety, residual depression and mood regulation,18 statistically significant effects appear only in within-group analyses, and they are not maintained in comparison with the control groups.17 According to systematic reviews,17–19 13 articles (8 clinical trials) have assessed the clinical efficacy on depressive, hypo/manic, and anxiety symptoms as well as the possible effects on neurocognitive processes associated with BD. Effectiveness and feasibility of MBCT in BD20 as well as the efficacy of an on-line MBCT treatment in late-stage BD patients21 have also been evaluated. Only three of these clinical trials were randomized and controlled.22–24 The greatest randomized study included 95 euthymic/mild depressive BD out-patients.23 In this study, no differences in time to affective relapse were found (primary outcome) between MBCT and treatment as usual (TAU) control patients. Anxiety symptoms significantly improved during follow-up, and there were no between-group differences on depressive or manic symptoms. A later sub-analysis did show that longer and more frequent meditation time improved not only anxiety but also depression.23,25 Two small randomized studies22,24 as well as open studies26–28 have found efficacy in reducing both anxiety and depressive symptoms, and this improvement persists some months after intervention.29,30 A subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis finds data favorable to the reduction of depressive and anxiety symptoms, but insists on the need for more research.31 A recent qualitative study also suggests that MBCT is feasible for people with BD, but depressive symptoms could interfere with adherence.32 Recently, a preliminary study that includes mindfulness in an integrative approach with psychoeducation and functional remediation found improvements in psychosocial functioning and residual depressive symptoms in patients suffering from BD.33

Psychoeducation is the only first-line psychosocial intervention for the maintenance phase in BD patients, and according to Guidelines,2 should be offered to all patients. In summary, the evidence for the impact of MBCT on BD is not yet conclusive. Furthermore, there are no large-scale studies evaluating the efficacy of MBCT in bipolar patients with subthreshold depressive symptoms. The objective of our study was to assess the efficacy of MBCT as an adjunctive to TAU, compared with psychoeducation plus TAU and TAU, medication devoid of other specific psychosocial interventions, in bipolar disease subthreshold depressive patients. The main hypothesis was that the group of adjunctive MBCT would experience greater depressive symptom reductions than the other two study arms. Secondary hypotheses were that MBCT group could achieve major improvements in anxiety, functioning, and mindfulness skills, without worsening hypo/manic symptoms.

MethodsDesignThis is a randomized, prospective, multicenter, single-blinded clinical trial (NCT02133170) that has included BP-outpatients with subsyndromal depressive symptoms. Methods of the trial, inclusion and exclusion criteria have previously been described.34 In brief, patients with persistent mild/subsyndromal depressive symptoms were recruited from General Hospital and Mental Health Centers as well as Private Psychiatric Clinics and Bipolar Patient Associations via announcements or physician referral. To be enrolled in the study, patients had to be between 18 and 65 years old; BD diagnosis in clinical remission of acute mood episode at least in the three months prior to study; having experienced an acute affective episode in the past 3 years; and having suffered at least two lifetime depressive episodes; monotherapy or combination with a mood stabilizer (lithium valproate, carbamazepine or lamotrigine) at optimal doses (i.e., in serum levels within the therapeutic range: 0.6–1.2mEq/L for lithium, 50–100μg/mL for valproate, and 5–12mcg/mL for carbamazepine), or quetiapine monotherapy or in combination with the aforementioned stabilizers, or any oral atypical antipsychotic in combination with an antidepressant; a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]–17 score ≥8 and ≤19 and Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS] score<8. Being currently under the care of a psychiatrist and on stable medication according to current Guidelines were also required. In brief, exclusion criteria were: acute mood episode in the 12 weeks before the start of trial; diagnosis different from BD; risk of suicide; pregnancy; severe medical disease; being receiving psychotherapy or psychoeducation or received it in the past 5 years; being treated with different mood stabilizer than the mentioned in the inclusion criteria; participation in another clinical trial within 4 week; and mental retardation.

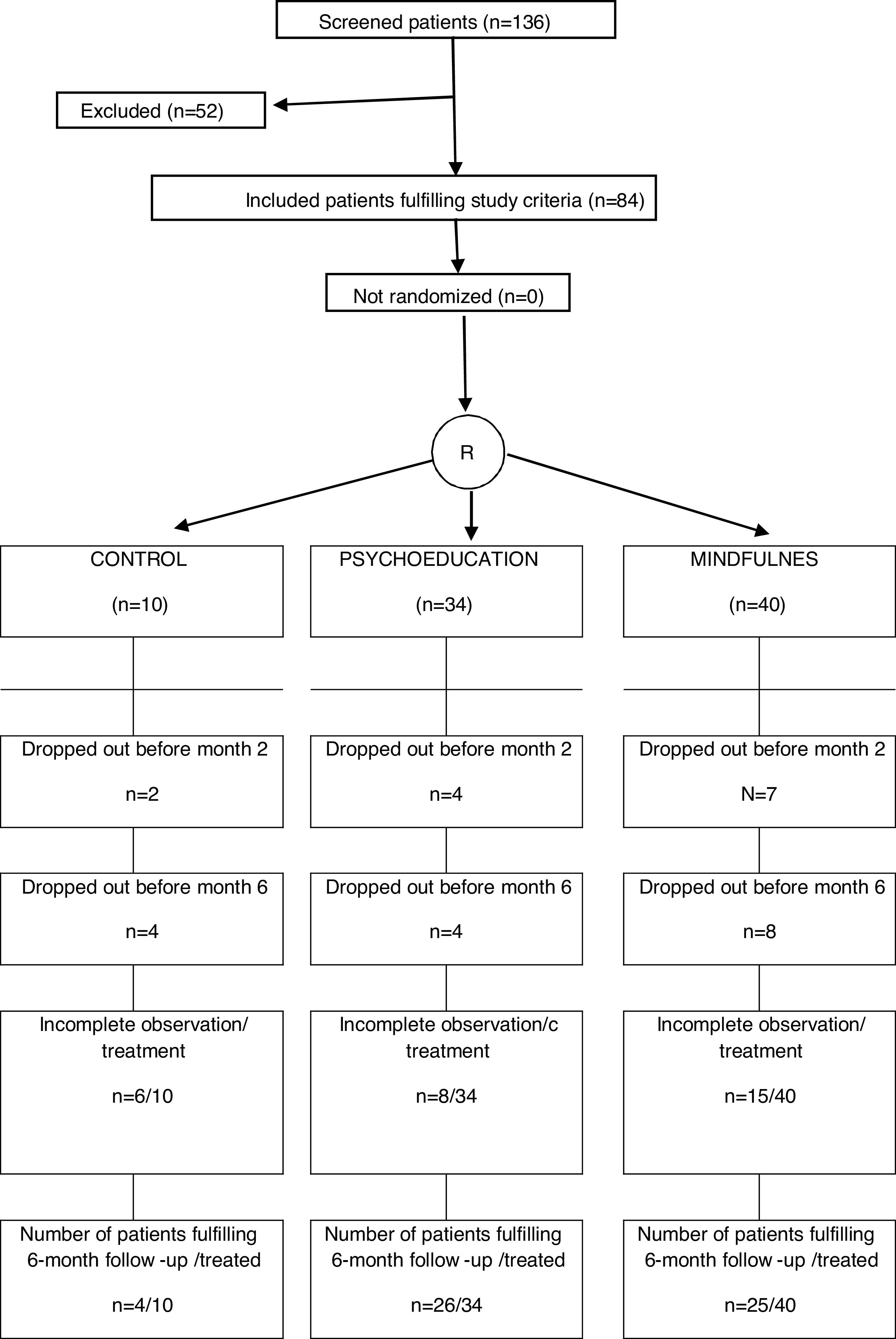

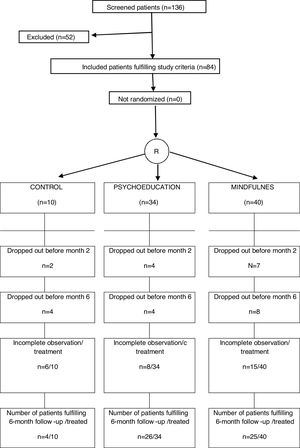

In this study, a total of 136 patients were screened, 84 patients were included, and 55 patients (65.5%) ended the full 6-month study duration. Twenty-eight patients were included in 2014, 13 patients in 2015, 18 patients in 2016, and 25 patients in 2017. The date of completion of the follow-up of the last patient included was July 20, 2018. Thirteen patients abandoned the study within the first 2 months and 16 more between 2 and 6 months (Fig. 1).

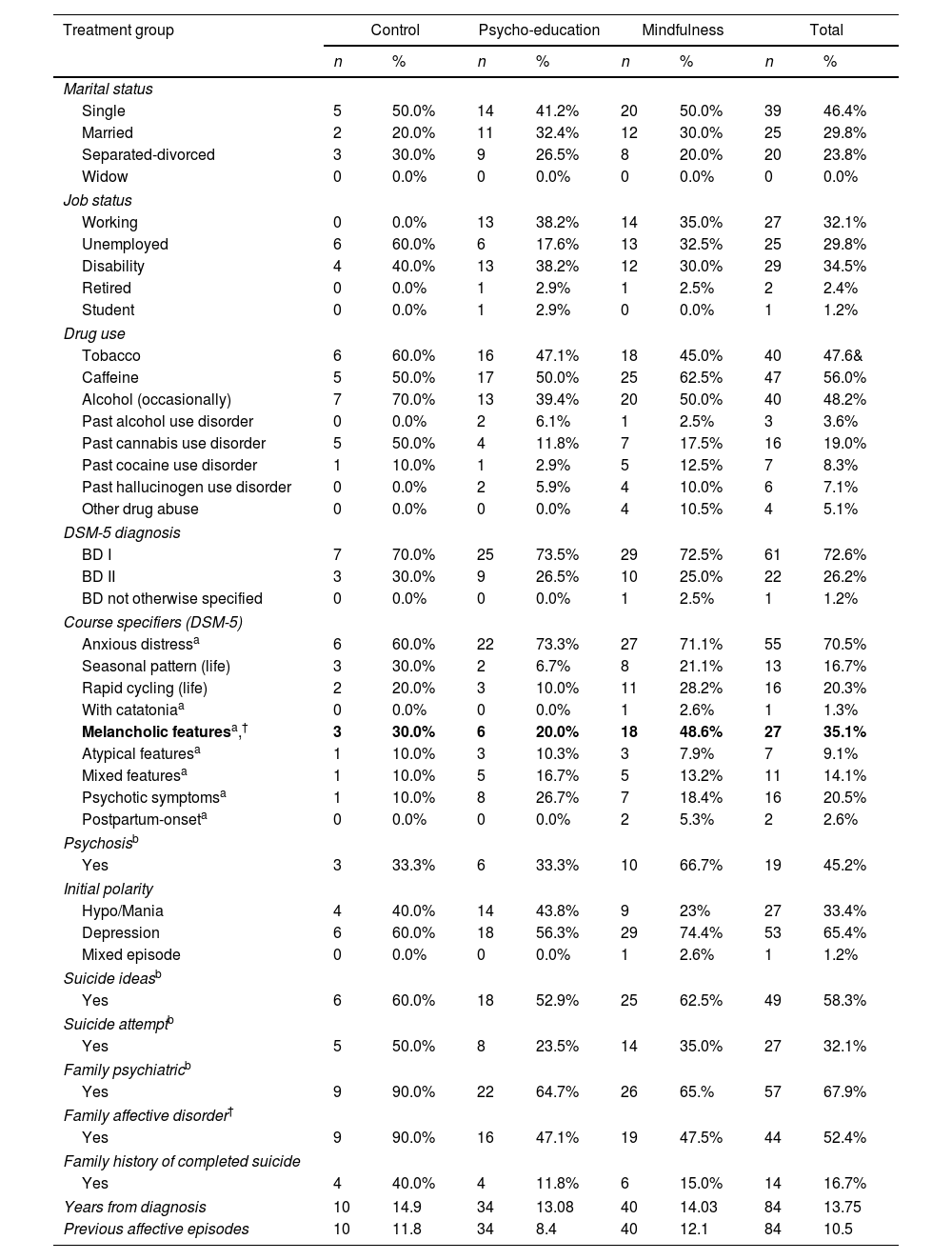

BD type I was diagnosed in 61 (72.6%), type II in 22 (26.2%) and BD not otherwise specified in 1 (1.2%) patient. Thirty patients (35.7%) were males. Mean age was 46.8 years, (95%CI, 44.5–49.1). Average time from symptom onset to the first visit was 20.5 years (95%CI 17.8–23.2), and time from diagnosis of BD was 13.8 years (95%CI 11.4–16.1), thus the diagnostic delay was 6.8 years (95%CI 4.9–8.7), with no differences between treatment groups.

After signature of informed consent, the 84 patients, 46 from La Paz University Hospital, 38 from Santiago Apostol Hospital, were randomly allocated (Random Allocation Software) to one of three groups: TAU control group, Psychoeducation plus TAU, and MBCT plus TAU. TAU implies standard psychiatric care with psychopharmacological treatment. Treatment group allocation was 1:4:4 proportion, respectively. Therefore, 10 patients received TAU, 34 psychoeducation and 40 MBCT.

All patients were assessed at baseline (V1), immediately after completing the program at 8 weeks (V2) and at 6 months (V3). Evaluation involved depression, anxiety, hypo/manic symptoms, affective episodes between visits, adherence to treatment, mindfulness skills and global functioning.

Study followed Consort checklist and international rules according to the Helsinki Declaration and local rules. Ethics Committees of the University Hospital La Paz (Madrid) and from the Basque Autonomous Community approved the study. Privacy of participants was guaranteed according to Spanish Law (LOPD 3/2018).

InterventionMBCT is a manualized group skills training program that integrates psychological educational aspects of CBT for depression with meditation components of mindfulness-based stress reduction developed by Kabat-Zinn.35 In our study, we followed the original MBCT program.11,36 The MBCT program consisted of 8 weekly sessions of 90min performed in groups. Brief written information about BD was given to the patients at the beginning of the therapy. Sessions were conducted by experienced therapists with certification in Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) and MBCT psychotherapy. Therapists were blind to the clinical evaluation. To ensure the fidelity of the treatment, therapy sessions were audio recorded and the first of them was evaluated using the Mindfulness- based Cognitive Therapy Adherence Scale (MBCT-AS) which assesses the key constructs of MBCT during group sessions.

Group psychoeducation involved also eight 2-h weekly sessions and approached several topics such as disease awareness and education, adherence and prodromal recognition, knowledge on available treatments and recommendations in case of relapse, based upon standardized group psychoeducation.37

Patients in TAU did not receive any structured psychosocial intervention or additional educational information on BD.

InstrumentsPrimary outcome was reduction in subsyndromal depressive severity, as assessed through the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS).38 Secondary outcomes were change in hypo/mania symptoms, anxiety, functioning and mindfulness, as well as number of affective relapses. Severity of mania symptoms was measured by Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).39 The severity of anxiety symptoms was measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A).40 Illness severity and change was measured by Clinical Global Impression Scale modified for Bipolar Disorder (CGI-BD-M). Psychosocial functioning was assessed through the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST).41 Mindfulness capacity has been assessed by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.42

Relapse into affective episode was considered to be present if any of the following criteria occurred: clinical criteria of depressive hypomanic, mixed or manic episode according to DSM 5, HDRS≥20 or YMRS≥8, need for a change of pharmacological treatment and/or admission for an affective episode.

Statistical analysisTo compare qualitative variables among intervention groups or among other breakdown factors we used Fisher or χ2 tests. For quantitative variables Student t test, Mann–Whitney, ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis, depending on the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov–Lilliefords normality tests and the number of categories in the comparisons. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was done with last observation carried forward imputation method for missing data substitution. The analysis of the change of the primary and secondary variables during follow-up was performed with a General Linear Model, ANOVA with repeated measures with two factors and repeated measures in one factor (Split Plot), with Bonferroni corrections for the control of the multiple comparisons error, which also allowed assessing whether statistically significant changes where present according to intervention group. Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 and two-tailed p<0.05 considered significant.

The initial sample size was expected to be of 140 patients, allowing a power of 80%. The post hoc power analysis for three levels in factor group of treatment, and two levels of follow-up from baseline to six months, of fixed effects analysis of variance for a total of 84 cases, yields a power of 52% to reach significance with an effect size (f=0.25) between treatment groups, and 63% to reach significance in the total group follow-up (f=0.25), and a power of 52% for the factors interaction (Sample Power, IBM-SPSS).

ResultsSample characteristicsThere were no statistically significant differences among groups in social and most clinical variables, including previous suicidal attempts (p=0.251), suicide attempt method (χ2=0.044, p=0.978), severity of suicidal behavior (p=0.797), family history of psychiatric disease (p=0.279), family history of completed suicide (p=0.101), and percentage of drop outs (p=0.241). There were imbalances among groups in melancholic course specifier for last episode (p=0.04) and family history of affective disorder (p=0.04). Other sociodemographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| Treatment group | Control | Psycho-education | Mindfulness | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 5 | 50.0% | 14 | 41.2% | 20 | 50.0% | 39 | 46.4% |

| Married | 2 | 20.0% | 11 | 32.4% | 12 | 30.0% | 25 | 29.8% |

| Separated-divorced | 3 | 30.0% | 9 | 26.5% | 8 | 20.0% | 20 | 23.8% |

| Widow | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Job status | ||||||||

| Working | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 38.2% | 14 | 35.0% | 27 | 32.1% |

| Unemployed | 6 | 60.0% | 6 | 17.6% | 13 | 32.5% | 25 | 29.8% |

| Disability | 4 | 40.0% | 13 | 38.2% | 12 | 30.0% | 29 | 34.5% |

| Retired | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 1 | 2.5% | 2 | 2.4% |

| Student | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.2% |

| Drug use | ||||||||

| Tobacco | 6 | 60.0% | 16 | 47.1% | 18 | 45.0% | 40 | 47.6& |

| Caffeine | 5 | 50.0% | 17 | 50.0% | 25 | 62.5% | 47 | 56.0% |

| Alcohol (occasionally) | 7 | 70.0% | 13 | 39.4% | 20 | 50.0% | 40 | 48.2% |

| Past alcohol use disorder | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 6.1% | 1 | 2.5% | 3 | 3.6% |

| Past cannabis use disorder | 5 | 50.0% | 4 | 11.8% | 7 | 17.5% | 16 | 19.0% |

| Past cocaine use disorder | 1 | 10.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 5 | 12.5% | 7 | 8.3% |

| Past hallucinogen use disorder | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 5.9% | 4 | 10.0% | 6 | 7.1% |

| Other drug abuse | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 10.5% | 4 | 5.1% |

| DSM-5 diagnosis | ||||||||

| BD I | 7 | 70.0% | 25 | 73.5% | 29 | 72.5% | 61 | 72.6% |

| BD II | 3 | 30.0% | 9 | 26.5% | 10 | 25.0% | 22 | 26.2% |

| BD not otherwise specified | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.5% | 1 | 1.2% |

| Course specifiers (DSM-5) | ||||||||

| Anxious distressa | 6 | 60.0% | 22 | 73.3% | 27 | 71.1% | 55 | 70.5% |

| Seasonal pattern (life) | 3 | 30.0% | 2 | 6.7% | 8 | 21.1% | 13 | 16.7% |

| Rapid cycling (life) | 2 | 20.0% | 3 | 10.0% | 11 | 28.2% | 16 | 20.3% |

| With catatoniaa | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.6% | 1 | 1.3% |

| Melancholic featuresa,† | 3 | 30.0% | 6 | 20.0% | 18 | 48.6% | 27 | 35.1% |

| Atypical featuresa | 1 | 10.0% | 3 | 10.3% | 3 | 7.9% | 7 | 9.1% |

| Mixed featuresa | 1 | 10.0% | 5 | 16.7% | 5 | 13.2% | 11 | 14.1% |

| Psychotic symptomsa | 1 | 10.0% | 8 | 26.7% | 7 | 18.4% | 16 | 20.5% |

| Postpartum-onseta | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 5.3% | 2 | 2.6% |

| Psychosisb | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 | 33.3% | 6 | 33.3% | 10 | 66.7% | 19 | 45.2% |

| Initial polarity | ||||||||

| Hypo/Mania | 4 | 40.0% | 14 | 43.8% | 9 | 23% | 27 | 33.4% |

| Depression | 6 | 60.0% | 18 | 56.3% | 29 | 74.4% | 53 | 65.4% |

| Mixed episode | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.6% | 1 | 1.2% |

| Suicide ideasb | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 60.0% | 18 | 52.9% | 25 | 62.5% | 49 | 58.3% |

| Suicide attemptb | ||||||||

| Yes | 5 | 50.0% | 8 | 23.5% | 14 | 35.0% | 27 | 32.1% |

| Family psychiatricb | ||||||||

| Yes | 9 | 90.0% | 22 | 64.7% | 26 | 65.% | 57 | 67.9% |

| Family affective disorder† | ||||||||

| Yes | 9 | 90.0% | 16 | 47.1% | 19 | 47.5% | 44 | 52.4% |

| Family history of completed suicide | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 40.0% | 4 | 11.8% | 6 | 15.0% | 14 | 16.7% |

| Years from diagnosis | 10 | 14.9 | 34 | 13.08 | 40 | 14.03 | 84 | 13.75 |

| Previous affective episodes | 10 | 11.8 | 34 | 8.4 | 40 | 12.1 | 84 | 10.5 |

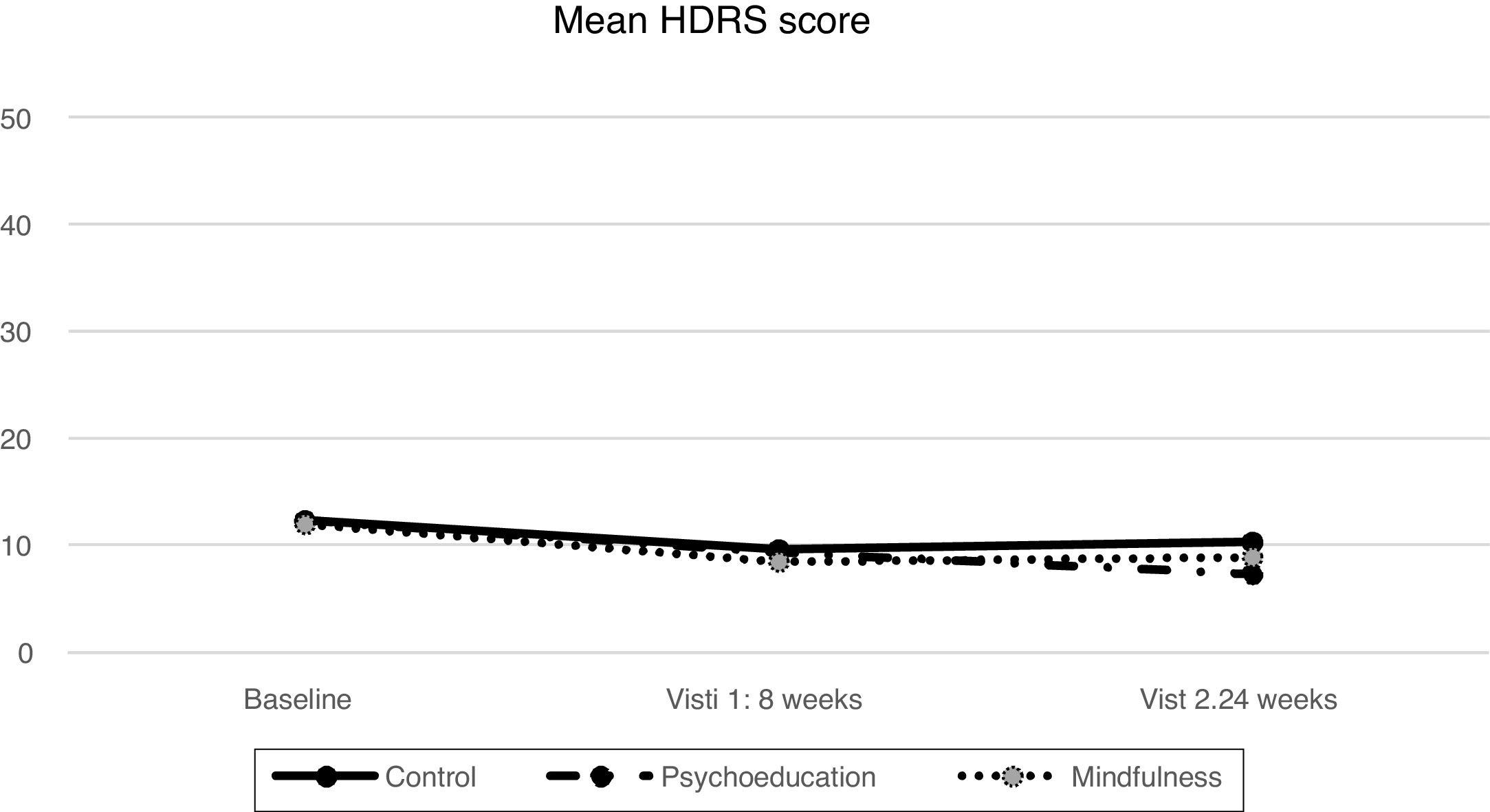

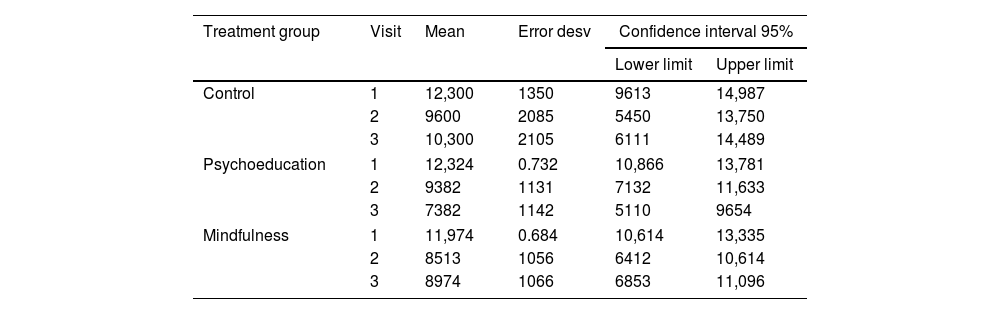

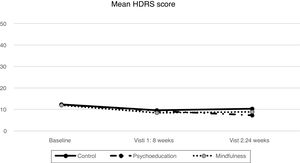

At baseline, there were no statistical differences among the three treatment arms in the HDRS score (mean 12.19; 95%CI, 11.08–13.31). Descriptive data is shown in Table 2. Depressive symptoms according to HDRS score improved in the whole sample between V1 and V2 (t=3.03; p<0001) and between V1 and V3 (t=3.31; p<0.0001), but did not change between V2 and V3 (t=0.28; p=1.0). There were no statistically significant differences in the scores of the three treatment arms at any time of follow-up (Fig. 2).

HDRS descriptive data.

| Treatment group | Visit | Mean | Error desv | Confidence interval 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Control | 1 | 12,300 | 1350 | 9613 | 14,987 |

| 2 | 9600 | 2085 | 5450 | 13,750 | |

| 3 | 10,300 | 2105 | 6111 | 14,489 | |

| Psychoeducation | 1 | 12,324 | 0.732 | 10,866 | 13,781 |

| 2 | 9382 | 1131 | 7132 | 11,633 | |

| 3 | 7382 | 1142 | 5110 | 9654 | |

| Mindfulness | 1 | 11,974 | 0.684 | 10,614 | 13,335 |

| 2 | 8513 | 1056 | 6412 | 10,614 | |

| 3 | 8974 | 1066 | 6853 | 11,096 | |

At baseline the three groups were homogeneous, mean YMRS 1.83 (95%CI, 1.29–2.36). This value did not change in the whole sample between visits, and this was also true for the three treatment arms (Table 3). V1 and V2, between V2 and V3 nor between V1 and V3. This was also true for the three treatment arms. There were no statistically significant differences, nor trends, among groups in each follow-up visits. In V1, control vs. psychoeducation control vs MBCT and psychoeducation vs MBCT.

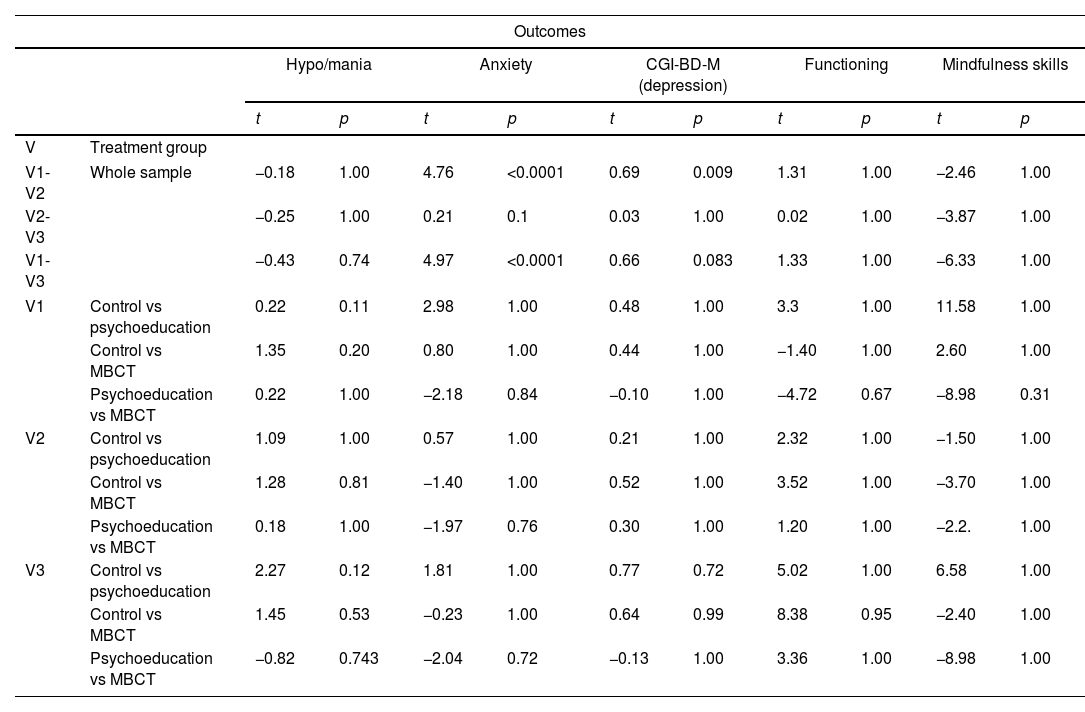

Secondary outcomes.

| Outcomes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypo/mania | Anxiety | CGI-BD-M (depression) | Functioning | Mindfulness skills | |||||||

| t | p | t | p | t | p | t | p | t | p | ||

| V | Treatment group | ||||||||||

| V1-V2 | Whole sample | −0.18 | 1.00 | 4.76 | <0.0001 | 0.69 | 0.009 | 1.31 | 1.00 | −2.46 | 1.00 |

| V2-V3 | −0.25 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 | −3.87 | 1.00 | |

| V1-V3 | −0.43 | 0.74 | 4.97 | <0.0001 | 0.66 | 0.083 | 1.33 | 1.00 | −6.33 | 1.00 | |

| V1 | Control vs psychoeducation | 0.22 | 0.11 | 2.98 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 3.3 | 1.00 | 11.58 | 1.00 |

| Control vs MBCT | 1.35 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 1.00 | −1.40 | 1.00 | 2.60 | 1.00 | |

| Psychoeducation vs MBCT | 0.22 | 1.00 | −2.18 | 0.84 | −0.10 | 1.00 | −4.72 | 0.67 | −8.98 | 0.31 | |

| V2 | Control vs psychoeducation | 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 2.32 | 1.00 | −1.50 | 1.00 |

| Control vs MBCT | 1.28 | 0.81 | −1.40 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 3.52 | 1.00 | −3.70 | 1.00 | |

| Psychoeducation vs MBCT | 0.18 | 1.00 | −1.97 | 0.76 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 1.00 | −2.2. | 1.00 | |

| V3 | Control vs psychoeducation | 2.27 | 0.12 | 1.81 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 5.02 | 1.00 | 6.58 | 1.00 |

| Control vs MBCT | 1.45 | 0.53 | −0.23 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 8.38 | 0.95 | −2.40 | 1.00 | |

| Psychoeducation vs MBCT | −0.82 | 0.743 | −2.04 | 0.72 | −0.13 | 1.00 | 3.36 | 1.00 | −8.98 | 1.00 | |

Changes in Hamilton Anxiety Score (HAM-A) were also assessed in all visits. At baseline, HAM-A score was homogeneous in the three groups and of mild or absent intensity (mean 14.34, 95%CI, 12.1–16.58). Anxiety symptoms according to HAM-A score improved in the whole sample between V1 and V2 and V1 and V3, but not between V2 and V3. There were no statistically significant differences in HAM-A score between groups in any visit (Table 3).

Clinical Global Impression (CGI-BD-M)Baseline score was homogeneous in the three study arms (mean 2.44, minimal or mild severity). Statistically significant differences were found for the CGI disease severity-depression in the whole sample between V1 and V2, but not between V1 and V3 nor between V2 and V3. No visit disclosed significant differences among treatment groups (Table 3). There were neither statistically significant differences in the total study sample in the CGI disease severity-mania, nor in the CGI disease severity-general.

FunctioningChanges in FAST score were assessed in V1, V2 and V3. Patients had moderate deterioration of functioning at baseline (mean 25.36, 95%CI, 20.12–30.60), without significant differences between groups. The score did not vary among visits in the global sample, and: V1-V2, V1-V3 and V2-V3. There were no significant differences, nor trends, between the three treatment arms in each visit (Table 3).

Mindfulness skillsAs with other variables, FFMQ was assessed in all visits. Baseline score showed no significant differences (mean 118.27; 95% CI, 108.97–127.58) between groups. There were not statistically significant differences in the scores in the total sample throughout the study: V1-V2; V2-V3 and V1-V3. The score also did not change among the three treatment groups in each visit: In V1 control vs psychoeducation; control vs MBCT and psychoeducation vs MBCT. For V2 control vs psychoeducation; control vs MBCT and psychoeducation vs MBCT. In V3, control vs psychoeducation; control vs MBCT and psychoeducation vs MBCT.

RelapsesThirteen patients (18.3%) relapsed in V2, and 10 (18.2%) in V3, with no significant differences among groups (p=0.32 and 0.18, respectively). Most relapses were mild and did not lead to study withdrawal.

Adverse eventsOne patient committed suicide immediately after the inclusion visit. This patient had been allocated to the control group and the event was not considered to be related to the study. Three patients suffered severe affective episodes during the follow-up and were excluded from the study. These adverse events were not judged to be related to the study intervention.

Drop-outs and withdrawalsOf the 84 patients of the sample, 13 signed out before the end of the intervention, and 16 abandoned in the last 4 months of the study. Fifty-five patients (65.5%) ended the full 6-month study duration (Fig. 1). Among the 29 drop-outs, 15 (51.7%) signed out claiming lack of interest in the study, 8 (27.6%) were excluded due to absence from more than two group sessions, 3 patients (10.3%) because of a severe affective relapse, and further 3 (10.3%) for other reasons (1 suicide and 2 for work-related reasons).

DiscussionThe objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of adjunctive MBCT compared to adjunctive psychoeducation vs unaided TAU on subthreshold depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder out-patients. The results of this randomly allocated study show that after 8 weekly sessions of MBCT, depressive symptoms significantly diminished compared to baseline depression score; nevertheless, this improvement was similar not only with that achieved in patients that followed structured group psychoeducation, but also with that attained in the small group of patients that received only treatment as usual. This absence of difference in the outcome among the three interventions is maintained at 6 months of follow-up. The three approaches also reduced anxiety without differences between them, and this reduction held at 6 months. Neither MBCT, nor psychoeducation nor TAU modified patients’ functioning according to FAST score. No treatment arm improved mindfulness skills. Hypo/manic symptoms did not worsen in the three groups, with no significant differences between them.

Affective and anxiety improvement in the three study arms could be linked to several factors. One may speculate whether there are common mechanisms of action in all three study arms. An example of this are the so-called common factors in psychotherapy (even support therapy, that is included in TAU), such as the link with the therapist, present in almost every modality of therapy43 which could act transversally. In the case of the two active arms, both have educational elements, potentially equalizing the efficacy of the two interventions.

The discrepancies between previous studies and ours must also be analyzed. Williams24 found reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, his sample included a very specific group of patients (only patients with previous suicidal ideation), of whom only 17 were bipolar patients, and compared them with cases in the waiting-list. Ives-Deliperi et al.44 found improvement of anxiety in MBCT, but in a very small sample with high degrees of anxiety and stress, as compared with patients in the waiting-list. No follow-up was described. Similarly, Perich et al.23 found reductions in anxiety with MBCT as compared with TAU. As in our study, they did not disclose changes in mania, depression or relapses between groups. Only 22 MBCT and 12 TAU patients completed follow-up in this study, although its duration was 12 months instead of 6, as is our case. This fact, as well as higher baseline anxiety scores in Perich's study, may explain this difference between their study and ours. Our sample showed baseline anxiety and mania scores within the normal range, and subthreshold depressive symptoms. Finally, Valls et al.33 found with an integrative approach improvement in psychosocial functioning and residual depressive symptoms. This intervention is a multi-component program so is difficult to know which components are responsible of the improvements. Besides, this program was longer (one more month). Thus, in our study it could happen that the low number of sessions was not enough to achieve significant improvements. In any case, mindfulness alone may offer fewer benefits to patients with bipolar disorder than combined with other ingredients to improve functioning and subsyndromic symptoms, or be more attractive for patients and promote well-being and functioning. The narrow margin for improvement (floor effect) may have hampered the finding of significant amelioration, as pointed out previously.17,18

To our knowledge, the present study has one of the largest sample sizes of published controlled studies assessing the efficacy of MBCT in bipolar subsyndromal depressive patients. Besides, it has been implemented comparing two active interventions and a treatment as usual control group, with a six-month follow-up. Furthermore, it is to date the only one that compares MBCT with psychoeducation in a specific bipolar population with subthreshold depressive symptoms, evaluating its implications in functioning. However, this relatively large sample size does not allow to rule out the possibility that existing differences were not detected (beta error). This limitation prevents to reach robust conclusions about the most effective approach to subsyndromal depressive symptoms, since mild cases can experience only small effect sizes with various treatment modalities. There is a theoretical controversy about the methodology of the large-scale randomized controlled trials applied to psychotherapy, traditionally transplanted directly from the pharmacological model. The cost in time and money of these trials is huge and the ideal sample size is not usually reached. Due these difficulties, some authors propose cohort-based designs for long-term psychotherapy for severe mental disorders.45

Furthermore, the intended 1:2:2 allocation ratio (TAU, TAU plus psychoeducation and TAU plus MBCT, respectively) could not be maintained. Due to the high expectations of patients for active treatment during recruitment, the ratio was changed to 1:4:4. However, the randomization of the study was rigorously maintained. The use of unequal randomization is increasingly frequent and there are several scenarios where it can be advantageous.46 The most important one is the majority preference of the patients, which was characteristic of our study. In these situations, some authors indicate ethical reasons for this unequal ratio, which minimizes the choice of placebo or no treatment.47 Finally, neither the time spent on doing homework nor homework review in the sessions were monitored, and some data suggest the relevance of the amount of practice.25,48

ConclusionMBCT program seemed to be feasible for people with BD, with good adherence to treatment and good applicability, even in outpatient public healthcare settings in two public hospitals. MBCT delivered by adequately trained providers does not carry adverse effects in BD population.17

Our study does not allow us to confirm the superiority of MBCT over psychoeducation or TAU in improving subsyndromal depressive symptoms; neither on anxiety, hypo/mania, relapses, or functioning. Future studies should consider larger sample sizes, as well as standardizing MBCT protocol to BD, perhaps with more prolonged approaches and registering and fostering home based training. It would be also important to consider a greater number of sessions for the groups, adapt the program specifically for these patients and include booster sessions.

Authors’ contributionConsuelo de Dios, Guillermo Lahera, Carmen Bayón y Beatriz Rodriguez-Vega designed the study. Consuelo de Dios, Ana González-Pinto y Maria Fe Bravo recruited the patients. The Bimind Group recruited and assessed the patient, and contributed to MBCT and Psychoeducation groups. Carmen Bayón and Beatriz Rodriguez-Vega conducted and coordinated the MBCT groups. Consuelo de Dios, Diego Carracedo and Guillermo Lahera wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to writing and revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

FundingThis work was funded by the Spanish grant FIS PI13/00352 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-financed with European Union ERDF funds.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Mrs. Begoña Soler (EC-BIO) for the statistical analysis, and J.L. Agud, for the assistant in preparation of the manuscript.

The BIMIND study group consist of: Caridad Avedillo, Carlos Casado, Alberto Flores, Jorge Guedes, Gonzalo González, Noelia Iglesias, Loreto Mellado, Roberto Mediavilla, Ignacio Millán, Víctor Romero, Iñigo Rubio, Daniel Trigo, Amaia Ugarte, Mauricio Vaughan, Patricia Vega, Rosa Villanueva.