One of the most frequent complications after a total hip arthroplasty (THA) is bleeding, intravenous tranexamic acid (TXA) is used to reduce it. We considered it necessary to carry out a study to clarify which administration route is superior.

Material and methodProspective, controlled and randomized study in 2 arms carried out between February 2017 and February 2018. 15mg/kg of intravenous TXA were administered in group A and 2g of intra-articular TXA in group B. The values of haemoglobin and haematocrit were evaluated at 24h-72h, blood loss volume, drained blood volume, transfusions and complications.

Results78 patients were included, 31 with intravenous treatment and 47 with intra-articular. The decrease of haemoglobin in the intravenous group was 3.15±1.64g/dl in 24h and 3.75±1.56g/dl in 72h, the haematocrit decreased by 10.4±4.17% in 24h and 11.85±4.15% in 72h. In the intra-articular group there was a haemoglobin fall of 3.03±1.30g/dl in 24h and 3.22±1.2g/dl in 72h and the haematocrit fell by 10.66±3.6% and 12.11±3.29% in 24 and 72h (p>.05). The mean drainage in 24h was 195.80ml in group A versus 253.93ml in group B (p>.05) and in 48h it was 225.33ml in group A and 328.19ml in group B (p=.009). The intravenous group lost an average of 1505ml of blood compared to the 11,280ml of the intra-articular group. In 5.1% of the cases, transfusions were necessary. We had no secondary complications.

ConclusionsThe different routes of administration of TXA in THA have a similar effect in the reduction of postoperative bleeding. There was no evidence of an increase in complications.

Una complicación frecuente tras una artroplastia total de cadera es el sangrado, y para reducirlo se utiliza el ácido tranexámico (TXA) intravenoso. Recientemente se han publicado los beneficios de su aplicación tópica. Consideramos necesario realizar un estudio que justifique qué vía de administración resulta superior.

Material y métodoEstudio prospectivo, controlado, aleatorizado en 2 brazos realizado entre febrero de 2017 a febrero de 2018. En el grupo A se administró 15mg/kg TXA intravenoso y en el B 2g TXA intraarticular. Se evaluó los valores de hemoglobina y hematocrito a las 24-72horas, volumen de sangre drenado, volumen de sangre perdida, transfusiones y complicaciones.

ResultadosFueron incluidos 78 pacientes, 31 con tratamiento intravenoso y 47 intraarticular. La hemoglobina descendió 3,15±1,64g/dl en 24horas y 3,75±1,56g/dl en 72horas en el grupo intravenoso, el hematocrito descendió un 10,4%±4,17% en 24horas y 11,85%±4,15% en 72horas. En el intraarticular se observó una caída de hemoglobina de 3,03±1,30g/dl en 24horas y de 3,22±1,2g/dl en 72horas y el hematocrito descendió 10,66%±3,6% y 12,11%±3,29% en 24 y 72horas (p>0,05). El drenaje medio en 24horas fue 195,80ml en el grupo A frente a 253,93ml en el grupo B (p>0,05) y a las 48horas 225,33ml en el grupo A y de 328,19ml en el grupo-B (p=0,009). En el grupo intravenoso perdieron una media de 1.505ml de sangre frente a 1.280ml del grupo intraarticular. Fueron necesarias un 5,1% de transfusiones. No tuvimos complicaciones secundarias.

ConclusionesLas diferentes vías de administración del TXA en la artroplastia total de cadera tienen un efecto similar en la reducción del sangrado postoperatorio sin evidenciar un incremento de complicaciones.

Total hip arthroscopy is one of the most common interventions in the treatment of osteoarticular hip pain secondary to arthrosis or avascular necrosis of the femoral head. One of the most frequent complications of surgery is large-scale intraoperative bleeding that will continue postoperatively. Previous studies have shown ranges of blood loss from 1.188ml to 1.651ml.1,2 Furthermore, it has been observed that between 10% and 38% of patients undergoing arthroplasty require an average 2units of packed erythrocytes to minimise the haemoglobin and haematocrit drop.3,4 No allogenic blood transfusion is risk-free, and in addition to adding to costs, it significantly increases complications: postoperative infections, hospital stay, mortality or delayed physical recovery, for example.5

Many strategies have been deployed to reduce postoperative bleeding and the number of transfusions after prosthetic surgery, including autologous donation, intraoperative controlled hypotension, regional anaesthesia, blood saving measures, erythropoietin and antifibrinolytic agents. Tranexamic acid (TXA), marketed as Amchafibrin® is the most powerful and has the fewest complications of the antifibrinolytic agents. Its administration inhibits the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, through blocking the lysine binding site, and prevents fibrin degradation.6,7

Previous orthopaedic and cardiovascular surgery studies have demonstrated that TXA reduces postoperative bleeding and the amount of allogenic transfusions compared to a control group using routine haemostasis.7,8 Moreover, it did not increase the number of thromboembolic events, or surgical infections.4,9 However, most of these prospective, randomized or meta-analysis studies have focussed on the effectiveness, efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid without specifying the optimal administration route.10–12 Recently the benefits of topical administration of TXA have been published, delivering a maximum concentration to the surgical site with low systemic effect.10 Therefore, we consider it necessary to undertake a study to clarify which administration route, topical or intravenous, is superior and equally safe in reducing postoperative bleeding after a primary hip arthroplasty. To that end we evaluated two independent parameters, the volume of blood drained and total blood loss, taking into account the need for transfusions. We presumed that the topical application (intra-articular) of TXA after closure would reduce postoperative bleeding and help maintain haemodynamic stability as well as its intravenous use. Our secondary aim was to analyse whether either of the administration routes reduced the number of allogenic blood transfusions and the incidence of possible thromboembolic events more than the other.

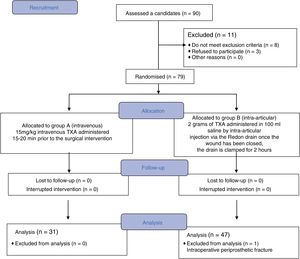

Material and methodDesignWe undertook a prospective and randomized, two-arm, phase IV clinical trial in the Doctor Peset University Hospital of Valencia after approval from the clinical research ethics committee. Group A (arm A) were given 15mg/kg of TXA intravenously 15–20min before the end of the surgical intervention. Group B (arm B) received 2 grams of intra-articular TXA in 100ml of saline via the Redon drain, once the wound had been closed; the Redon drain was then clamped for 2h.

The dose of TXA we used was based on previous studies according to routine clinical practice.13,14

We did not require a control group, because there is already sufficient published literature demonstrating the usefulness and safety of TXA as an antifibrinolytic agent to reduce postoperative bleeding, which is already marketed as Amchafibrin®.

Study population and sample sizeThe study was performed on patients who underwent elective total hip arthroplasty due to coxarthrosis or avascular necrosis in the period between February 2017 and February 2018.

Given that at the time of starting the study there were no publications describing differences in the use of intravenous or intra-articular TXA after a total hip prosthesis, we used a time criterion to calculate the sample size.

All the patients who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively randomized by intervention demand into 2 groups or arms, group A, who received intravenous treatment with TXA plus routine haemostasis, and group B, who received intra-articular treatment plus routine haemostatis. During the study the orthopaedic surgeon and the anaesthetist were not blinded due to the different tranexamic acid administration routes. However, the entire subsequent follow-up was undertaken homogeneously and in a standardised way for the 2 groups.

Selection criteriaInclusion criteriaAll patients aged between 18 and 85 who had undergone a total hip replacement due to primary coxarthrosis or avascular necrosis were included in the study. The patients had to have signed their informed consent for the surgical intervention and to take part in the study, and have a recent lab test result confirming normality of platelet count, INR and prothrombin time.

Exclusion criteriaAll patients who were allergic to tranexamic acid, those who refused to participate in the study, those with a secondary arthropathy (rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis), cardiovascular disease (acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, angina, grade 3–4 heart failure, prior heart surgery), cerebrovascular disease (stroke, transient ischaemic attack and vascular surgery, thromboembolic disease (deep vein thrombosis [DVT], fibrinolysis disorders and coagulopathies (if INR>1.4, platelets<150,000×109/l, prothrombin time>1.4), liver and/or kidney failure, treatment with anticoagulants 7 days prior to the surgical intervention, blood product rejection, intraoperative complications (anaesthetic or surgical), those participating in another clinical trial, and with preoperative haemoglobin levels<12g/dl were excluded from the study.

Variables studiedThe patients’ sociodemographic variables were collected (age at the time of the intervention, sex, weight, height and body mass index), medical history, preanaesthetic assessment and variables relative to the intervention (such as the type of anaesthesia used, approach, surgical time, days of hospital stay and laterality). The main clinical variables collected were preoperative and postoperative haemoglobin and haematocrit (at 24h and 72h), the lowest haemoglobin recorded during the hospital stay, the patient's blood volume (Annex 1), total blood loss (Annex 2), hidden blood loss (Annex 3), and the drainage volume at 24 and 48h (ml). In addition, the number of blood units transfused and the complications from the intervention (the wound developing infection or necrosis, DVT, PTE or death) were gathered as secondary variables.

The centre's surgical protocolAll the interventions were performed by a team of orthopaedic surgeons with experience in primary hip arthroplasty. All the patients received cementless models.

In the anaesthetic induction intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered according to the hospital's infections committee. During the entire operation haemostatis was undertaken using electrocoagulation of the blood vessels. After the intervention we placed a number 12 vacuum drain, which was removed after 48h. The topical TXA (group B) was inserted via the Redon drain, once the wound had been closed, which was then clamped for 2h. The Redon drains of the patients receiving intravenous TXA (group A) were opened after placing the compression bandage. Six hours after the surgical intervention the patients received venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with low molecular weight bemiparin, which was maintained for 30 days.

All the patients who were admitted followed the same blood transfusion protocol based on the perioperative transfusion guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference.15 Red blood cell transfusion was indicated should the patient's haemoglobin levels fall below 8g/dl, or below 10g/dl if they had associated cardiopulmonary disease and symptoms of anaemia, defined as syncope, fatigue, palpitations or dizziness.

Any complications such as thromboembolic events were noted and collected throughout the patients’ hospital stay. On discharge, all the patients were given outpatient appointments 3 weeks after the intervention, when any possible complications were assessed.

Data collectionThe patient data collection was undertaken homogeneously and in a standardised way for the 2 groups. The data were collectively postoperatively by a different team of surgeons. The haemoglobin levels and haematocrit at 24 and 72h following the surgery, the daily drained blood volumes, whether or not a blood transfusion had been given, and a series of the abovementioned demographic variables were recorded. In this assessment phase the analysis was blinded. In addition, confusion bias was avoided since these were objective results.

Statistical analysisFirstly a descriptive analysis was undertaken where normally distributed continuous variables were described as mean±standard deviation (SD), and those that were not normally distributed, or non-Gaussian, were described as median (maximum–minimum). The qualitative variables were described in frequencies and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the variables’ normality distribution. The χ2 test was used to study the association between qualitative variables. The Student's t-test, Mann–Whitney U test or ANOVA were used to study the differences between means according to the application conditions. Differences with p<.05 were considered statistically significant in all the tests. The computer analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0.

Ethical aspectsThis paper was completed after the approval of the Doctor Peset University Hospital's ethics committee, in compliance with the recommendations of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All the patients included in the study signed their informed consent.

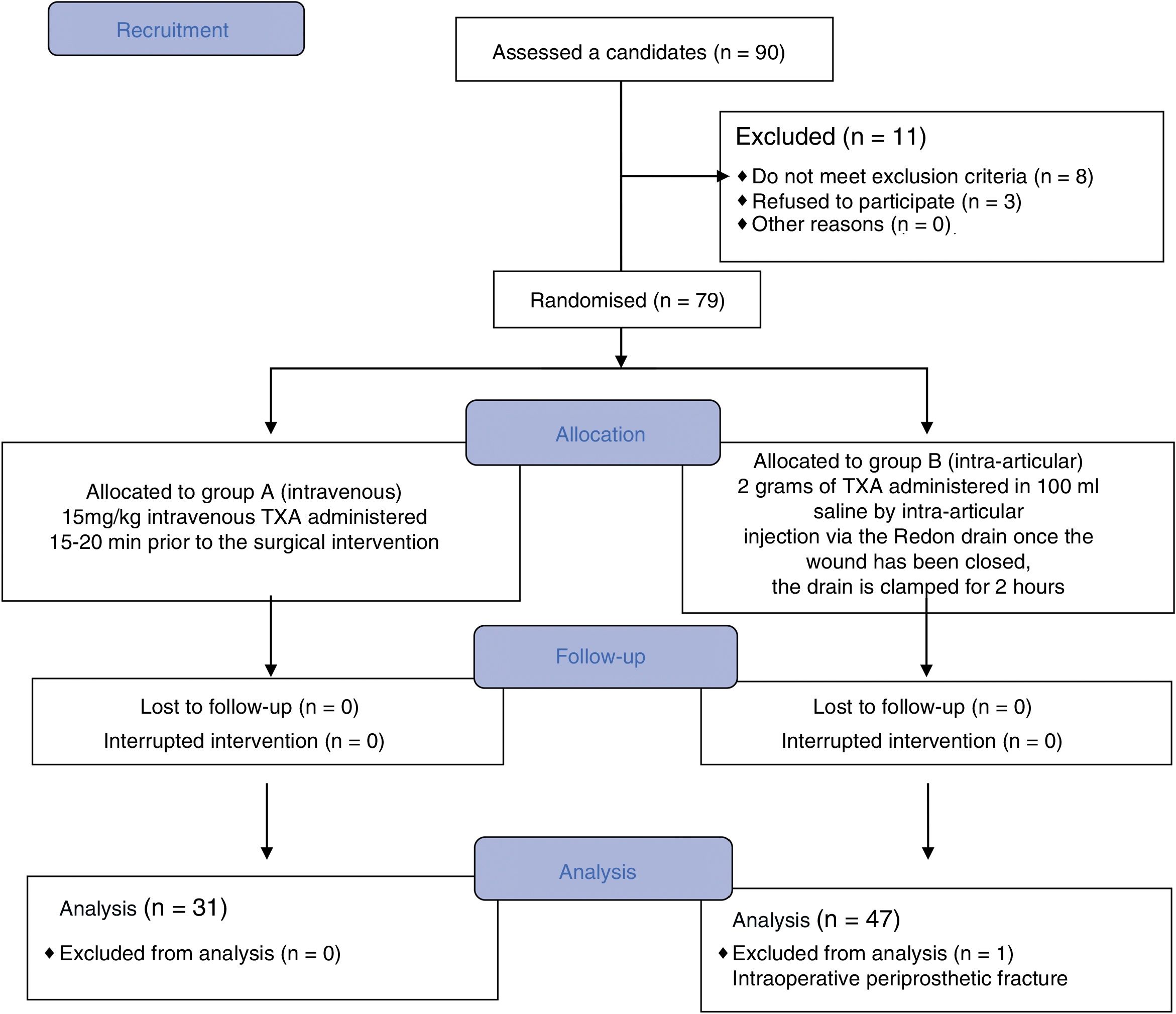

ResultsBetween February 2017 and February 2018, 90 patients scheduled for primary hip arthroscopy were included in the study. Of this initial group, 12 patients were excluded from the study, 8 because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, 3 because they did not want to participate, and one case was excluded during the follow-up when an iatrogenic fracture was confirmed that required intraoperative transfusions. The final analysis was undertaken on 78 patients, of whom 31 were randomized to group A and received the intravenous treatment, and 47 patients to group B who received intra-articular TXA (Fig. 1).

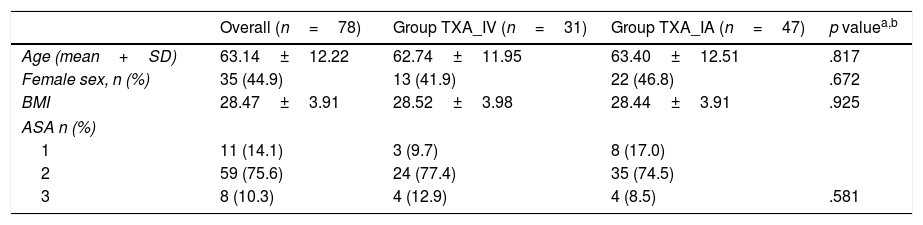

No significant differences were found in terms of age, sex, body mass index or American Society of Anesthesiologists’ classification16 (Table 1). The comorbidity associated with the surgical intervention was gathered and assessed; chronic diseases such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipaemia under treatment were found in 66.66% of the patients (52 cases).

Description of the sample according to the TXA administration route.

| Overall (n=78) | Group TXA_IV (n=31) | Group TXA_IA (n=47) | p valuea,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean+SD) | 63.14±12.22 | 62.74±11.95 | 63.40±12.51 | .817 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 35 (44.9) | 13 (41.9) | 22 (46.8) | .672 |

| BMI | 28.47±3.91 | 28.52±3.98 | 28.44±3.91 | .925 |

| ASA n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 11 (14.1) | 3 (9.7) | 8 (17.0) | |

| 2 | 59 (75.6) | 24 (77.4) | 35 (74.5) | |

| 3 | 8 (10.3) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (8.5) | .581 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; SD: standard deviation, BMI: body mass index; n: number.

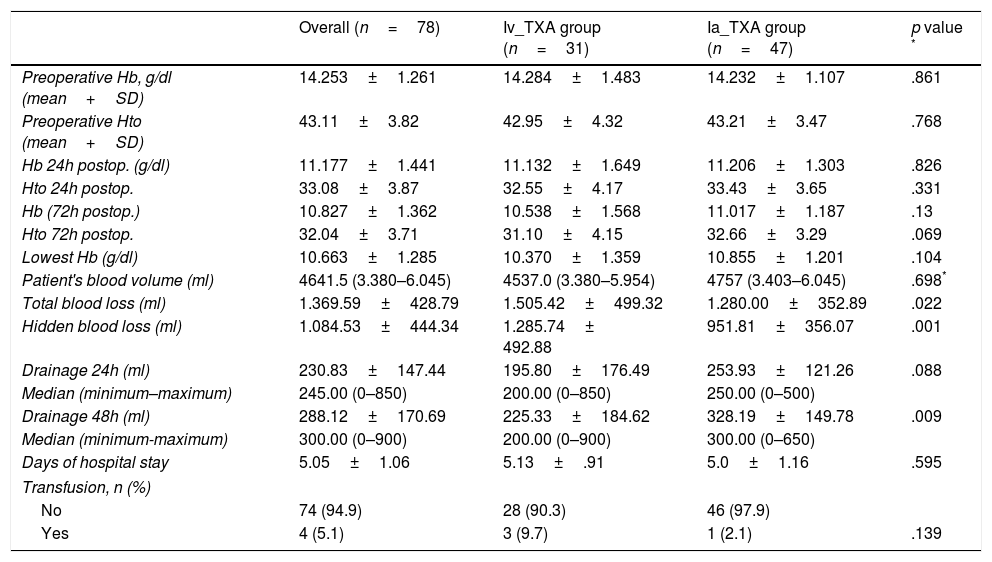

The preoperative haemoglobin levels and haematocrit were similar in both groups. The fall in haemoglobin and mean haematocrit after the intervention was also similar. In group A, who received intravenous TXA, we started with a mean preoperative Hb of 14.28g/dl, with a mean fall at 24h of 3.15±1.64g/dl, and of 3.75±1.56g/dl at 72h. The haematocrit suffered a mean drop of 10.4±4.17% at 24h, and of 11.85±4.15% at 72h. In group B, with the intra-articular administration, we started with a mean Hb of 14.23g/dl, and a mean fall of 3.03±1.30g/dl was observed at 24h, and of 3.22±1.2g/dl at 72h. The haematocrit dropped 10.66±3.6% and 12.11±3.29% at 24 and 72h respectively. The lowest recorded mean haemoglobin levels were 10.3g/dl for group A, and 10.8g/dl for group B. We found no significant differences between either group in any of the values studied (Table 2).

Drainage levels and haemoglobin (HB) levels and haematocrit (Htc) pre and post surgery. Median (minimum and maximum).

| Overall (n=78) | Iv_TXA group (n=31) | Ia_TXA group (n=47) | p value * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative Hb, g/dl (mean+SD) | 14.253±1.261 | 14.284±1.483 | 14.232±1.107 | .861 |

| Preoperative Hto (mean+SD) | 43.11±3.82 | 42.95±4.32 | 43.21±3.47 | .768 |

| Hb 24h postop. (g/dl) | 11.177±1.441 | 11.132±1.649 | 11.206±1.303 | .826 |

| Hto 24h postop. | 33.08±3.87 | 32.55±4.17 | 33.43±3.65 | .331 |

| Hb (72h postop.) | 10.827±1.362 | 10.538±1.568 | 11.017±1.187 | .13 |

| Hto 72h postop. | 32.04±3.71 | 31.10±4.15 | 32.66±3.29 | .069 |

| Lowest Hb (g/dl) | 10.663±1.285 | 10.370±1.359 | 10.855±1.201 | .104 |

| Patient's blood volume (ml) | 4641.5 (3.380–6.045) | 4537.0 (3.380–5.954) | 4757 (3.403–6.045) | .698* |

| Total blood loss (ml) | 1.369.59±428.79 | 1.505.42±499.32 | 1.280.00±352.89 | .022 |

| Hidden blood loss (ml) | 1.084.53±444.34 | 1.285.74± 492.88 | 951.81±356.07 | .001 |

| Drainage 24h (ml) | 230.83±147.44 | 195.80±176.49 | 253.93±121.26 | .088 |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 245.00 (0–850) | 200.00 (0–850) | 250.00 (0–500) | |

| Drainage 48h (ml) | 288.12±170.69 | 225.33±184.62 | 328.19±149.78 | .009 |

| Median (minimum-maximum) | 300.00 (0–900) | 200.00 (0–900) | 300.00 (0–650) | |

| Days of hospital stay | 5.05±1.06 | 5.13±.91 | 5.0±1.16 | .595 |

| Transfusion, n (%) | ||||

| No | 74 (94.9) | 28 (90.3) | 46 (97.9) | |

| Yes | 4 (5.1) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (2.1) | .139 |

SD: standard deviation; n: number.

The mean drainage values in the first 24h were 195.80ml in group A with intravenous administration compared to 253.93ml collected from group B, with the intra-articular administration. At 48h, prior to removing the drain, a mean drainage of 225.33ml was recorded for group A compared to the 328.19ml of group B; there was a statistically significant association (p=.009) in the values collected at 48h. If we analyse the patient's blood volume and calculate the total blood loss after the surgery we see that the intravenous group lost 1505.42±499.32ml, while the intra-articular group lost 1280.00±352.89ml, showing a statistically significant association (p=.022).

The proportion of patients who required a transfusion was 9.7% in group A, whereas in group B 2.1% of the cases received a transfusion.

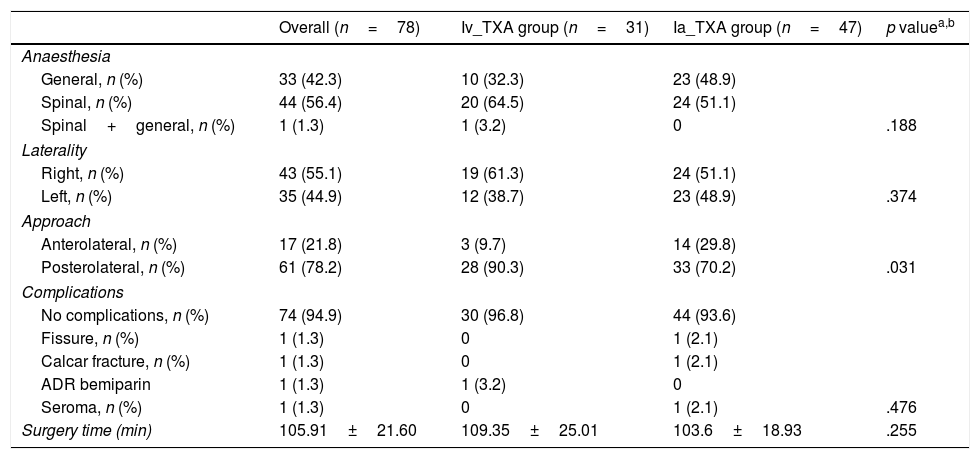

The surgery time and mean hospital stay were similar in both groups, with no statistically significant association (Table 3).

Description of the sample in relation to the characteristics of the intervention and according to the administration of tranexamic acid (TXA).

| Overall (n=78) | Iv_TXA group (n=31) | Ia_TXA group (n=47) | p valuea,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthesia | ||||

| General, n (%) | 33 (42.3) | 10 (32.3) | 23 (48.9) | |

| Spinal, n (%) | 44 (56.4) | 20 (64.5) | 24 (51.1) | |

| Spinal+general, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (3.2) | 0 | .188 |

| Laterality | ||||

| Right, n (%) | 43 (55.1) | 19 (61.3) | 24 (51.1) | |

| Left, n (%) | 35 (44.9) | 12 (38.7) | 23 (48.9) | .374 |

| Approach | ||||

| Anterolateral, n (%) | 17 (21.8) | 3 (9.7) | 14 (29.8) | |

| Posterolateral, n (%) | 61 (78.2) | 28 (90.3) | 33 (70.2) | .031 |

| Complications | ||||

| No complications, n (%) | 74 (94.9) | 30 (96.8) | 44 (93.6) | |

| Fissure, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | |

| Calcar fracture, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | |

| ADR bemiparin | 1 (1.3) | 1 (3.2) | 0 | |

| Seroma, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | .476 |

| Surgery time (min) | 105.91±21.60 | 109.35±25.01 | 103.6±18.93 | .255 |

SD: standard deviation; n: number; ADR: adverse drug reaction.

In terms of complications, of a total 78 operated patients, we only had 4 cases with complications (2 calcar fractures, one case of symptoms of allergic reaction to bemiparin and one surgical infection). No thromboembolic complications or complications secondary to the TXA administration route were found in the immediate postoperative period or in the follow-up (Table 3).

DiscussionTotal hip arthroplasty involves significant intra- and postoperative blood loss. The onset of postsurgical anaemia can increase mortality and morbidity, increase length of hospital stay and delay rehabilitation.17 Different processes have been developed over many years in order to minimise blood loss, and thus prevent allogenic blood transfusion, an invasive technique associated with major complications.2 Many studies report the benefits of tranexamic acid in reducing postoperative bleeding.8,18,19 There has been increasing interest in the topical administration of TXA in recent years due to its direct application to the surgical site with local action which minimises systemic side effects.10,20,21 When tranexamic acid is given intravenously it distributes intracellularly and extracellularly until it reaches its maximum concentration after 5–15min, increasing its risk of causing thromboembolic complications.10,22,23 In our randomized clinical trial we demonstrated that there are no statistically significant differences in the topical administration of 2g of tranexamic acid compared to the standard treatment of 15mg/kg intravenously, in terms of falls in haemoglobin and haematocrit, blood loss and the need for transfusions. In a recently published meta-analysis similar results to ours were obtained in terms of reduced bleeding and minimising transfusions.23 However, unlike our results, they observed less of a fall in haemoglobin in the intravenous group, without being able to ensure the superiority of this route; probably due to insufficient data.

Many studies have demonstrated that the intra-articular route is not inferior to the standard intravenous administration after a total knee arthroplasty,4,12–14 some authors even recommend intra-articular administration as more effective, since it is a direct and simple route that can be used for patients for whom the systemic use of TXA is contraindicated, since its absorption from the joint is not very clinically significant.24 We found few publications on the hip that refer to statistically significant differences in decreased bleeding according to the administration route, and the few we did find defend the intravenous route.25,26 Our study found very similar results, but always with less total blood loss and lower falls in haemoglobin in the intra-articular group, and there was a statistically significant association in some values. Likewise, the patients in the intra-articular administration group received fewer transfusions compared to the intravenous group, and although we did not obtain a statistically significant result and we cannot confirm the superiority of one route over the other, this constant tendency towards better results using the intra-articular route has encouraged us to use it in our clinical practice.

The administration of tranexamic acid has proved a safe technique, since we have had no increase in complications (PTE, DVT or deep infections). Only one patient in group B developed a seroma that required surgical cleaning and intravenous antibiotic therapy for 7 days. However, most authors recommend the topical route for patients with a potential risk of thromboembolic events.23

Most publications make no mention of surgery time,18 therefore they consider that it might influence blood loss. In our study we assessed the surgery time of the intravenous group (109.35±25.01min) compared to the topical group (103.6±18.9min), and found no statistically significant differences.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, we used sequential randomisation excluding patients with major cardiovascular comorbidities, i.e., potentially thromboembolic patients. Furthermore, the number of cases allocated to each group was not equal, and was too small to be able to demonstrate a statistically significant association. Different surgeons participated which might have led to unequal intraoperative bleeding. We excluded patients who required intraoperative blood transfusions to prevent potential biases in monitoring a population with no intraoperative complications. And finally, in our hospital we do not perform routine screening for PTE or DVT, and therefore only Doppler ultrasonography was indicated in the event of clinical suspicion. Any complications might have been underestimated if there had been any asymptomatic thromboembolic events. The strengths of this paper are that it was a prospective, randomized study with team of doctors, surgical nurses and operating theatre that follow a rigorous protocol of action and data collection.

The doses of tranexamic acid that should be prescribed are still a matter of controversy. Studies on the dose regimens are very heterogeneous, and probably require larger samples to obtain valid results. Our study used 15mg/kg intravenously and 2g via the intra-articular route; our doses were based on similar regimens recommended in Ref.17

ConclusionThe different administration routes for tranexamic acid that we studied for primary total hip arthroplasty (topical intra-articular versus intravenous) have a similar effect in reducing postoperative bleeding. We found no increase in complications with either of the 2 established regimens. However, we prefer the intra-articular route for patients with a thromboembolic risk. Further studies are required with a larger number of cases to establish the optimal dose of tranexamic acid.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Patient's blood volume=(k1×height [m3])+(k2×weight [kg])+k3

- -

Males: K1=.3699/K2=.3219/K3=.6041

- -

Females: K1=.3561/K2=.03308/K3=.1833

Total blood loss=patient's blood volume×(Hct(pre)−Hct(post)/mean Hct)

Hidden blood loss=total blood loss−drained volume at 72h.

Please cite this article as: Gómez Barbero P, Gómez Aparicio MS, Blas Dobón JA, Pelayo de Tomás JM, Morales Suárez-Varela M, Rodrigo Pérez JL. Aplicación del tranexámico intravenoso o intraarticular en el control del sangrado posquirúrgico tras una artroplastia total de cadera. Estudio prospectivo, controlado y aleatorizado. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:138–145.