An analysis was made on relationship between Notching and functional and radiographic parameters after treatment of acute proximal humeral fractures with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

MethodsA retrospective evaluation was performed on 37 patients with acute proximal humeral fracture treated by reversed shoulder arthroplasty. The mean follow-up was 24 months.

Range of motion, intraoperative and postoperative complications were recorded. Nerot's classification was used to evaluate Notching. Patient satisfaction was evaluated with the Constant Score (CS).

Statistical analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between Notching and glenosphere position, or functional outcomes.

ResultsMean range of elevation, abduction, external and internal rotation were 106.22°, 104.46°, 46.08° and 40.27°, respectively. Mean CS was 63. Notching was present at 12 months in 29% of patients. Statistical analysis showed significance differences between age and CS, age and notching development, and tilt with notching. No statistical significance differences were found between elevation, abduction, internal and external rotation and CS either with scapular or glenosphere-neck angle.

ConclusionReverse shoulder arthroplasty is a valuable option for acute humeral fractures in patients with osteoporosis and cuff-tear arthropathy. It leads to early pain relief and shoulder motion. Nevertheless, it is not exempt from complications, and long-term studies are needed to determine the importance of notching.

Evaluar la relación entre el Notching y los resultados clínico-funcionales y radiológicos tras el tratamiento de las fracturas de húmero proximal con prótesis invertida de hombro (PTHi).

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de 37 pacientes con fracturas de húmero proximal tratadas mediante PTHi con seguimiento medio de 24 meses. Se evaluó: tipo de fractura, rango de movilidad postoperatoria (antepulsión [AP], abducción [ABD], rotación externa [RE] y rotación interna [RI]), complicaciones y grado de satisfacción del paciente mediante la escala de Constant (CS). Se constató desarrollo de Notching según la clasificación de Nerot. Análisis estadístico de la relación Notching-posición de la glenosfera y resultados funcionales.

ResultadosLos rangos medios de movilidad fueron AP 106,22°, ABD 104,46°, RE 46,08° y RI 40,27°. Se produjo Notching en el 29% de los pacientes al año de seguimiento. El valor medio del CS fue de 63 a los 18 meses post-IQ. Fueron estadísticamente no significativas las relaciones:

Notching – balance articular final,

Notching – CS,

Notching – ángulo del cuello de la escápula,

Notching – ángulo de la glena,

Notching – distancia del bulón al borde inferior de la glena.

Se encontró significación estadística entre la edad y el desarrollo de Notching y el Notching y el Tilt glenoideo.

ConclusionesLa PTHi es una opción en pacientes con osteoporosis y artropatía del manguito rotador que presentan fractura humeral proximal. Permite alivio rápido del dolor y una funcionalidad aceptable. No está exenta de complicaciones: son necesarios estudios a largo plazo para determinar la relevancia del Notching.

Proximal humeral fractures are one of the most frequent pathologies to present in emergency services, particularly in patients over 65 years of age.1 In the case of 3–4 fragment fractures in this age group (particularly when associated with luxation of the glenohumeral joint) there is controversy regarding the treatment of choice since the fractures are usually associated with osteoporosis, a pre-existing pathology of the rotator cuff, and other comorbidities.2

The use of locking plates appears to be a good solution, but complications frequently present, including loss of reduction, intra-articular penetration of screws and osteonecrosis of the humeral head, affecting between 21% and 75% of these patients.3

Hemiarthroplasty as a therapeutic option has proven to lead to acceptable pain relief, but studies to date show variable results, where the anatomic repair of tuberosities plays an essential role.4 In elderly patients with low bone reserves, it is difficult to reduce tuberosities and achieve satisfactory fixation.5,6

In these cases, reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) is a good therapeutic alternative. The deltoid muscle plays an essential role here; as it compensates for rotator cuff deficiency by the creation of a stable rotation centre in the glenoid muscles that enables both active abduction and flexion of the arm. The design of this type of implant strengthens the function of the deltoid muscles, as the centre of rotation is displaced both medially and distally, increasing the tensile force of the deltoid fibres and reducing the twisting force exerted on the glenoid muscles.7

The most frequent complication after an RSA is the appearance of notching. Notching is the erosion of the scapular neck secondary to its contact with the humeral component of the implant during upper extremity adduction.8

The aim of our study was to evaluate the mid-term clinical and functional outcomes and complications of complex proximal humeral fractures treated with RSA in our hospital, and discover a possible statistical correlation between: functional outcomes and notching; age and the development of notching; the presence of notching and articular movement; the position of the glenosphere and posterior development of radiographic notching; notching and the Constant Scale (CS).

Material and methodsWe carried out a retrospective, observational, and descriptive study in the Traumatology Unit of our hospital.

Our study protocol included all patients with severe proximal humeral fractures treated with RSA from January 2009 until December 2013, who met with the established inclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients over 65, who were able to perform basic everyday activities independently, and who presented with proximal humeral fractures at risk of osteonecrosis of the humeral head, according to Hertel's criteria,9 and who were operated within 30 days after the date of trauma, with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months.

Patients excluded from the study were those who had been treated with RSA due to osteosynthesis failure or inveterate luxations, and for patients treated with hemiarthroplasty or conservative treatments.

Out of a total of 63 patients treated with RSA, 37 met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study.

In our study protocol we evaluated:

- -

Fracture type: classified according to the Neer and AO classifications.

- -

Laterality.

- -

Measurement of postoperative range of motion: propulsion, abduction and shoulder rotation.

- -

Development of intraoperative complications (Notching, according to the Sirveaux and Nerot classification,8 infections and vasculo-nervous lesions, etc.).

- -

CS.

In all cases surgery was performed under general anaesthetic with the patient placed in the sitting beach-chair position, assisted by intraoperative fluoroscopy.

Surgery was performed on all our patients by the same surgeon (JHE) who used a deltopectoral approach. The long head of the biceps was located, marked and sectioned for tendodesis at the end of the procedure. The humeral head fragment and residual supraspinatus were then removed. The tuberosities were located and marked using non-resorbable polyester Ethibond™ type number 5.0 sutures for subsequent reinsertion. The standard technique was then used, exposing the glenospere for subsequent milling. This procedure must be carefully performed since with fractures of this type the subchondral bone is usually osteoporotic. The metaglene was inserted in a neutral position or with a slight downward tilt. Prior to inserting the humeral component 2 perforations were made in the lateral area of the humeral cortex and non-resorbable sutures were passed through them, to allow for posterior reinsertion of the tuberosities as a tension band through them. The AequalisTM Reversed II (Tornier®) was the implanted prosthesis in all cases. The upper edge of the pectoralis major tendon was used as an anatomical reference point for the depth of the implanted humeral component, located approximately 5.5cm caudally to the upper section of the humeral head.

Drainage devices connected to vacuum systems were attached to all patients and removed 48h after surgery, coinciding with the initial postoperative healing phase. The limb was kept in a sling for one week. One day after surgery Codman pendulum exercises and passive elevation exercises were initiated.

Two weeks after surgery check-ups were performed on the patients to remove the staples; passive movement of the limb was then allowed. All patients were sent to the hospital's physiotherapy unit and began isometric resistance exercises 6 weeks after surgery. The check-ups took place after 6 weeks and at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after surgery; control X-rays were taken at all check-ups in the conventional true anteroposterior (Grashey view) and lateral transthoracic positioning of the shoulder.

Similarly to Simovitch et al.10 the following radiographic variables were assessed:

- (a)

The following was measured preoperatively:

- -

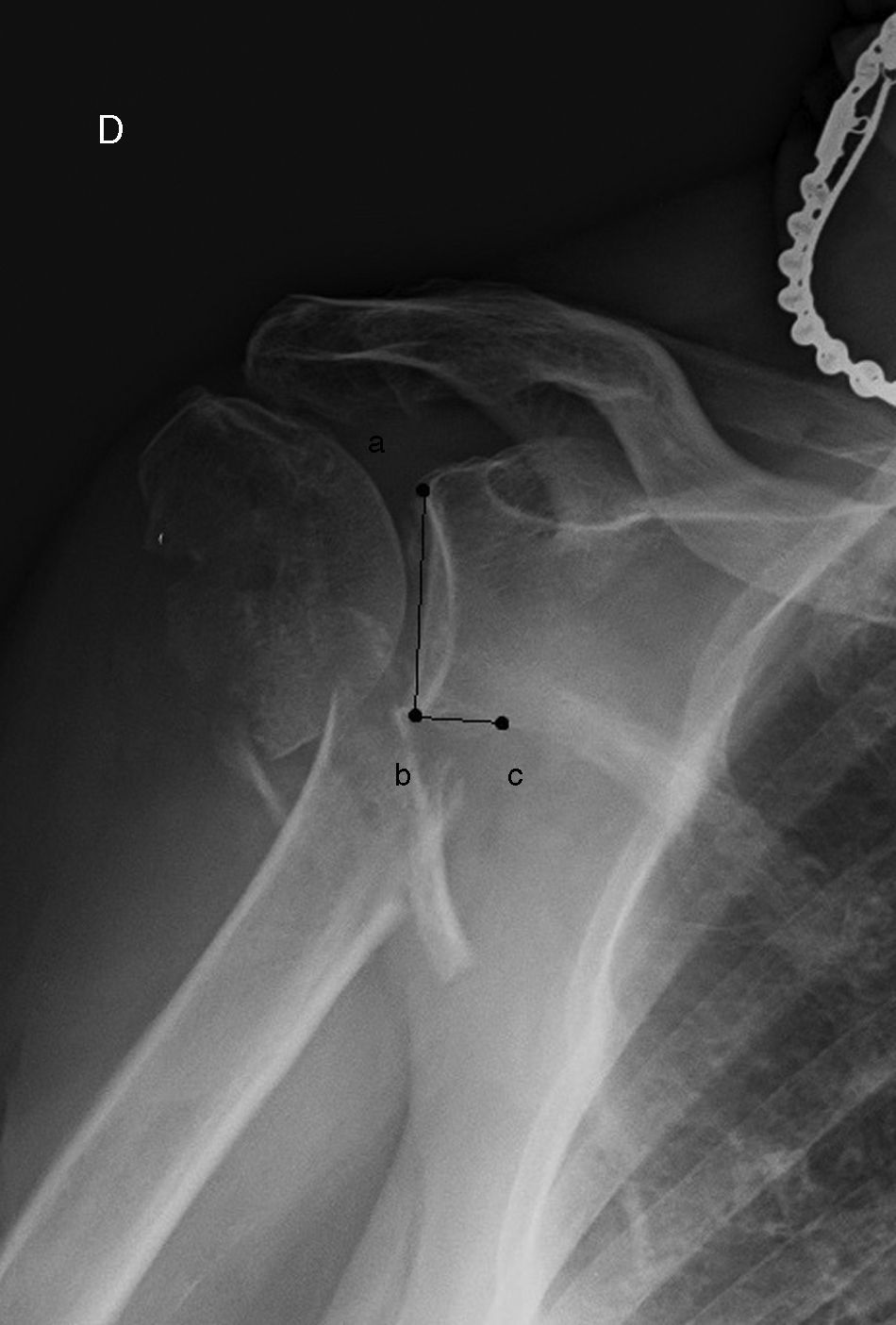

The angle of the scapular neck (Grashey view X-ray of the fractured side): formed by the intersection of a line traced from the upper edge of the glena to its lowest point, and from the lowest point of the glena to another located one centimetre medially along the glenoid flange (Fig. 1).

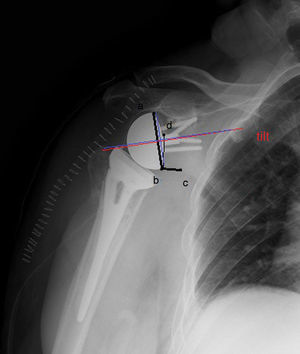

Figure 1.Angle of the scapula neck (in the true anteroposterior positioning of the fractured shoulder): formed by the intersection of a line traced from the upper edge of the glenosphere (point a) to its lowest point (b) and from the lowest point of the glenosphere (b) to another point positioned one centimetre medially following the glenoid flange (c).

- -

- (b)

In the postoperative control check-up the following was evaluated:

- -

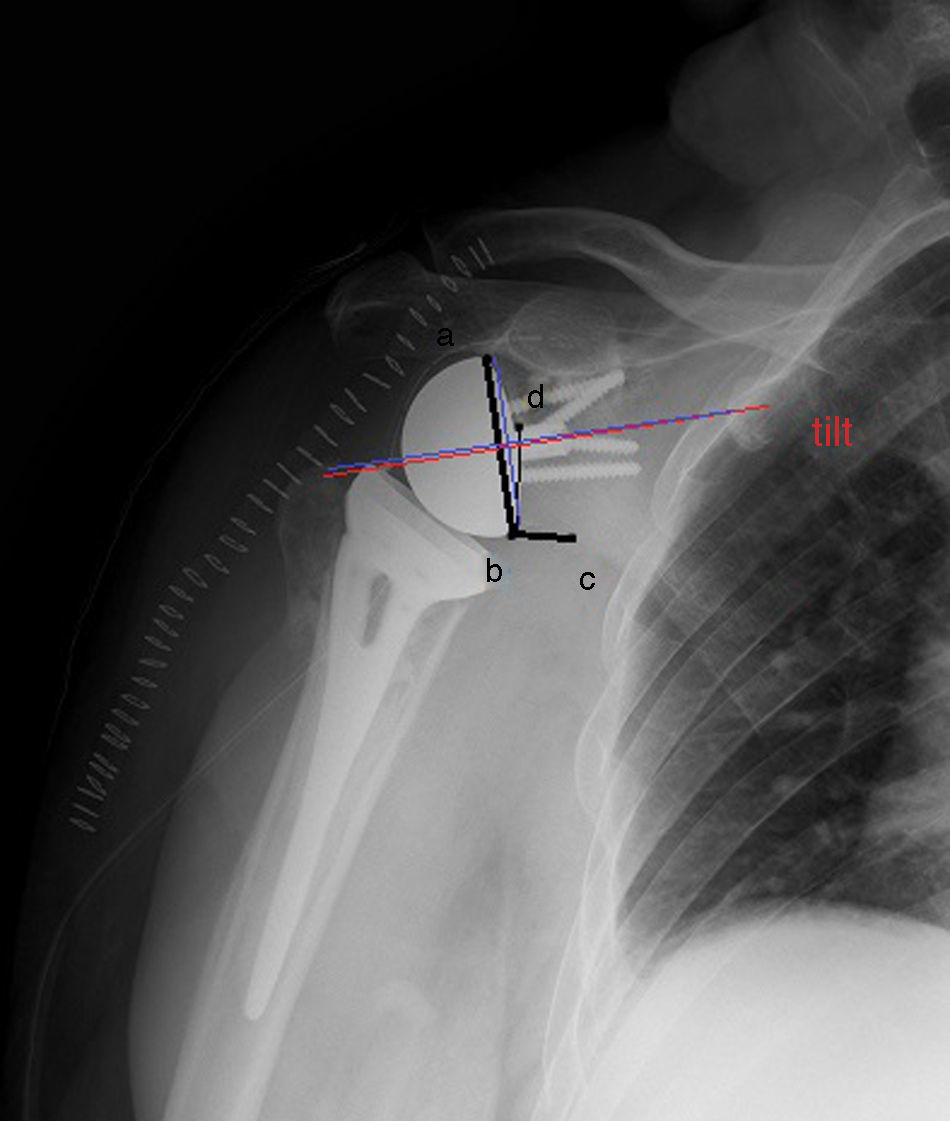

Scapular neck prosthesis angle: formed by the intersection of a line extending from the uppermost point of the metaglene to its lowermost point and another from the lower edge of the metaglene to one centimetre medially along the glenoid flange (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.Prosthesis-scapular neck angle: formed by the intersection of a line extending from the uppermost point of the metaglene (a) to its lowest point (b) and another from the lowest point of the metaglene (b) to one medial centimetre to the same following the glenoid flange (c). The distance of the pin to the lower edge of the scapula: distance from the upper edge of the pin (d) to the lower edge of the glenoid flange (b). Tilt (outlined in red): angle formed by the intersection of a parallel line of the metaglene pin axis and another perpendicular to the glenoid neck (blue line). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

- -

Distance from the pin to the lower edge of the scapula: distance from the upper edge of the pin to the lower edge of the glenoid flange (Fig. 2).

- -

Glenoid tilt: angle formed by the intersection of a parallel line to the pin axis of the metaglene and another perpendicular to the glenoid neck. This is considered neutral when it is equal to zero degrees, positive when the resulting angle tilts in a caudal direction (glena tilting downwards) and negative when the angle measured has a cranial tilt (glenosphere tilting upwards).

- -

- (c)

After 12 months the following was assessed:

- -

The existence or non-existence of notching and the extent of it, according to Nerot and Sirveaux's classification.

- -

18 months after surgery clinical and functional assessment was made using the CS.

Statistical analysisThe SPSS programme version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for descriptive statistical analysis and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparing the type of fracture with the CS, age, and articular movement. Radiographic measurements were used for comparing the development of notching.

ResultsOut of a total of 63 RSA patients, 37 met the inclusion criteria and presented a follow-up of 18 months or more. 36 were women (97.3%) and only one was a man (2.7%). The mean age was 77 (66–86 years of age). In 59% of cases it was the right shoulder that was injured.

According to Neer's classification, 54% were 4-fragment fractures, 30% were 3-fragment fractures and 16% were facture luxations. 33% of fractures were classified as 11C2, 32% as 11C3, 16% as 11B3, 11% as 11B2 and 8% as 11C1; the AO classification system was used. Metaphysary extension was present in six fractures.

Range of motion was as follows:

- -

Mean abduction of 104.46±25.38°.

- -

Mean propulsion of 106.22±16.89°.

- -

Mean internal rotation of 40.27±15.04°

- -

Mean external rotation of 46.08±21.95°.

The mean results of radiological measurements were as follows11:

- -

Scapular neck angle: 105±9.3 (90–135)°.

- -

Scapular prosthesis angle: 113.8±10.5 (95–130)°.

- -

Distance from metaglene: 25±1.6 (21–28)mm.

- -

Tilt (°): 9–7±5.8 (3–20)°.

The patients from the study demonstrated a good level of subjective satisfaction; the mean score of the patients studied was 63, the absence of pain in our patients was worthy of note (mean score for this parameter was 14 points out of 15).

The majority of patients did not suffer from any associated complication; 29% of them (n=12) developed notching, which was grade 1 in 75% of cases (n=9) and grade 2 in the other 25% (n=3). 19% (n=7) needed intraoperative metaphysary cerclage, in 6 cases as a consequence of the initial metaphysary extension of the fracture and in just one case due to intraoperative fracture. Two patients developed retropectoral haematoma which did not require surgical debridement. Treatment with oral antibiotics was administered for 7 days in these 2 cases as prophylaxis against a possible infection resulting from the haematoma. Another patient developed neuropraxis of the axillary nerve (probably due to retractors during surgery) and recovered favourably.

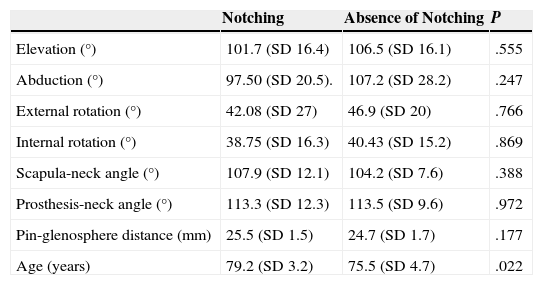

Statistical analysis of the resultsOn assessment of the relationship between the presence of notching and articular movement, and the development of notching and the CS scale no statistical significance was found (P=.55, P=.24, P=.76, P=.86 for propulsion, abduction, external and internal rotation respectively and P=.325).

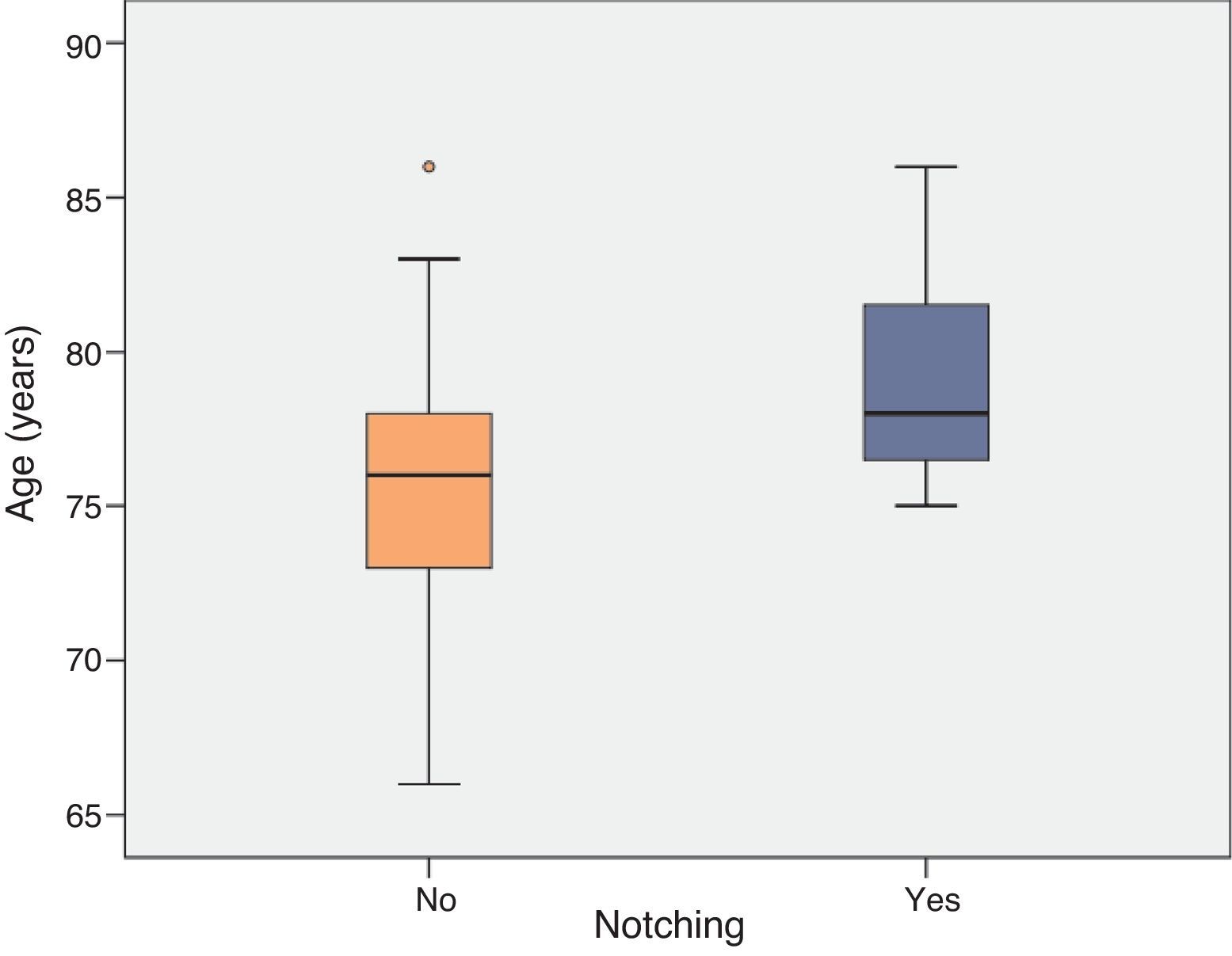

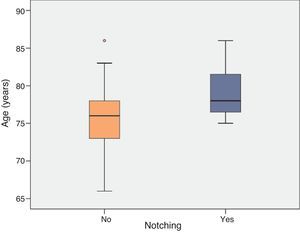

However, when assessing the relationship between age and the development of radiographic notching statistically significant differences were found (P=.022; Fig. 3).

With regards to the relationship between the presence of notching and the different radiographic variables which were measured (scapular neck angle, distance of the central flange of the metaglene to the inferior glenoid edge and the glenoid tilt), only statistical differences between the different stages of notching and tilt (P=.01) were apparent, with the appearance of notching mainly in those cases with less tilt (Table 1).

Relationship between notching and articular movements, radiographic measurements and age. Mann–Whitney U-test.

| Notching | Absence of Notching | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation (°) | 101.7 (SD 16.4) | 106.5 (SD 16.1) | .555 |

| Abduction (°) | 97.50 (SD 20.5). | 107.2 (SD 28.2) | .247 |

| External rotation (°) | 42.08 (SD 27) | 46.9 (SD 20) | .766 |

| Internal rotation (°) | 38.75 (SD 16.3) | 40.43 (SD 15.2) | .869 |

| Scapula-neck angle (°) | 107.9 (SD 12.1) | 104.2 (SD 7.6) | .388 |

| Prosthesis-neck angle (°) | 113.3 (SD 12.3) | 113.5 (SD 9.6) | .972 |

| Pin-glenosphere distance (mm) | 25.5 (SD 1.5) | 24.7 (SD 1.7) | .177 |

| Age (years) | 79.2 (SD 3.2) | 75.5 (SD 4.7) | .022 |

SD, standard deviation.

The treatment objective of proximal humeral fractures is the restoration of painless articular mobility of the shoulder as existed prior to the fracture.

There is a wide range of therapeutic options for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures. At present, no unified criteria exists for the indication of different treatment types. We select a therapeutic strategy according to fracture pattern, functional demands and the bone quality of the patient. The clinical and functional results of the different therapeutic options are not always satisfactory, particularly in elderly people with bones weakened by osteoporosis and/or 3 or 4 fragment fractures or fractures-luxations where there is a high risk of osteonecrosis of the humeral head.

At present, the most commonly used osteosynthesis system consists of locking plates which offer greater stability to fixation of osteoporotic bone and enable earlier rehabilitation. As a result, better functional results are obtained than with other methods of fixation. However, this is a technically demanding system with a high rate of complications. The most frequently reported complication is loss of reduction and intra-articular penetration of screws. Other less frequent complications are the development of avascular necrosis of the humeral head and the lack of repair or pseudoarthrosis.3,11,12

Hemiarthroplasty is another therapeutic option which has proven to provide an acceptable level of pain relief. However, results were variable from the series we consulted with the main cause of failure being the migration or repair failure of tuberosities, altering the function of the rotator cuff.13,14

Based on these data, the use of RSA would seem reasonable as a first therapeutic option in patients with a high risk of hemiarthroplasty failure (patients over 65 years of age, those with tuberosities in a precarious condition, a previous rotator cuff lesion or which cannot be immobilised over a long period of time).15

With regards to surgical technique, we used the deltopectoral approach as this does not affect the deltoids, as their integrity is essential for the prosthesis to function correctly. It has also been suggested that this assists the lower positioning of the glenosphere and fixation of tuberosities.16 We routinely cement the humeral component since these patients are normally osteoporotic and the fracture line usually extends to the metaphysis, as occurred in 6 of our patients who required intraoperative cerclage.17

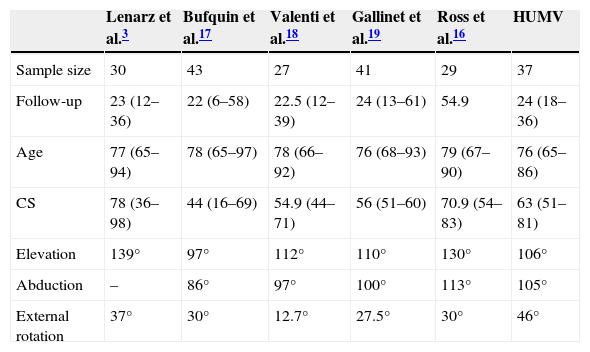

Functional results published to date are favourable, with mean propulsion of 97°17–139°3,and CS of 4417–783.

Both age and the functional outcomes obtained in our study are comparable to those obtained by other authors3,16–19 (Table 2). In our series the mean age was 76. The mean age in published studies ranges between 76 and 79 years of age, with no patients under 65 years of age. Mean follow-up in our study was 24 months (18–36). Studies published to date show a similar mean follow-up, except for the series published by Ross et al.16 with a mean follow-up of 54.9 months (see Table 2). With regards to articular movement, in our series we would suggest that the mean external rotation is somewhat greater than that shown in other publications, at the expense of a loss of internal rotation; this is probably due to implantation of the humeral component with greater retroversion than that mentioned by other authors. When an RSA is performed due to arthropathy of the rotator cuff, it is recommended that the humeral component be implanted with a retroversion of 0–30°20. Gulotta et al.21 in a study with specimens, used CT on inverted prostheses implanted at 0°, 20°, 30°, and 40° retroversion to assess muscle forces by means of a simulator to externally abduct and rotate the glenohumeral joint at 30° and 60° and the existence or non-existence of impingement. They concluded that the increase in retroversion did not alter the muscle force required for external abduction and rotation but that retroversion increased external rotation in the absence of impingement, reducing internal rotation. They recommend retroversion of 0°–20° to maximise internal rotation when the arm is in adduction and to facilitate basic everyday activities. In the case of RSA performed after a fracture, the extent of retroversion is more difficult to establish intraoperatively due to the fracture.20

Comparison between our results and previous references.

| Lenarz et al.3 | Bufquin et al.17 | Valenti et al.18 | Gallinet et al.19 | Ross et al.16 | HUMV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 30 | 43 | 27 | 41 | 29 | 37 |

| Follow-up | 23 (12–36) | 22 (6–58) | 22.5 (12–39) | 24 (13–61) | 54.9 | 24 (18–36) |

| Age | 77 (65–94) | 78 (65–97) | 78 (66–92) | 76 (68–93) | 79 (67–90) | 76 (65–86) |

| CS | 78 (36–98) | 44 (16–69) | 54.9 (44–71) | 56 (51–60) | 70.9 (54–83) | 63 (51–81) |

| Elevation | 139° | 97° | 112° | 110° | 130° | 106° |

| Abduction | – | 86° | 97° | 100° | 113° | 105° |

| External rotation | 37° | 30° | 12.7° | 27.5° | 30° | 46° |

The patients analysed in our study show a good level of satisfaction in the functional CS. Pain relief is one of the most consistent benefits of this surgical intervention. In our series the great majority of patients mentioned the absence of pain, with a score of 14 out of 15 in the CS.

The functional outcomes are acceptable after a short period of immobilisation aimed at relieving pain, the patient has sufficient articular movement to carry out basic everyday activities without pain.

Notwithstanding, as suggested by our results, this type of surgery is not exempt from complications. The development of notching is one of the most frequent complications, with a range of 5–53%17,22 in the published series. Its long-term repercussions have yet to be determined. As explained previously, this phenomenon is due to contact between the humeral component of the implant and the scapular neck in adduction of the upper extremity. Notching does not occur exclusively from treatment of proximal humeral fracture, it also occurs in RSA performed as a result of other aetiologies.23 In our series we assessed the presence of notching at 12 months follow-up; it has been documented that this complication occurs rapidly during the first 14 months and stops progressing at 18 months.10 Levigne et al.24 reported the existence of notching in 62% of their RSAs, this fell to 38% when the aetiology was post-traumatic.24 The incidence of notching in our study was 23% (type 1 in 75% of cases and type 2 in the other 25%), similar to that of other studies published, with no incidence of mobilisation of the glenoid component after one year of follow-up.17

At present, it is well-known that the patient's own anatomical traits and the positioning of the glenoid implant influence the development of scapular notching.25 Regarding the positioning of the glenoid component, in line with other studies, we found that there was a statistically-significant relationship between the tilt of the glenosphere and the presence of notching,10 so that when prostheses were implanted with a higher degree of tilt, the notching was lower. Unlike Simovitch et al.10 we found no statistically-significant relationship between the distance of the pin to the lower edge of the glena and the angle of the neck of the prosthesis with notching. However, it is logical to think that a lower implantation of the glenosphere and the presence of a sharper prosthesis-neck angle would prevent notching from occurring. The absence of statistical significance in our study could be due to the fact that we had fewer patients than in the Simovitch series, or to other factors which were not assessed, such as obesity, for example (obese patients cannot adduce their arm to the same extent as a non-obese patient and this would prevent the development of this effect).

With regards to other factors, we found there was statistical significance in the relationship between age and subsequent development of notching. In the case of RSA performed after arthropathy of the rotator cuff, it is known that notching correlates with preoperative factors such as the degree of fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus muscle or narrowing of the acromiohumeral interval.24 Degeneration of fat tissue increases with age, and may therefore be the indirect cause of the relationship between age and notching found in our series.

In line with other studies8,24 we did not find a statistically-significant relationship between the existence of this effect and the articular movement of the patient or the score obtained in the CS. There are studies which contradict these findings, however, and report that in the long term there is a reduction in CS and an increase in pain in patients with notching.10

Based on our clinical and radiological results, on the statistical analysis of our study and on international medical literature consulted, the authors of this article have reached the conclusion that total inverted arthroplasty is a good alternative in the treatment of complex proximal humeral fractures in patients over 65 with poor bone quality and a previously affected rotator cuff, provided that a skilled surgeon with experience in this field performs the operation. Our secondary conclusion would be that the study has served to make us more aware of common complications such as notching. We are unaware of its effects long term which is why further studies are required for analysis. However, we believe that it can be prevented by increasing glenoid tilt.

We are aware of the limitations of our work; this is a retrospective observational study with no control group with which to compare results. Furthermore, the radiographic parameters were assessed by a single observer, and it is therefore possible that some measurements were influenced by radiographic projection. The evaluation of the existence or non-existence of notching was carried out within a short period (12 months). However, this study has some strengths: surgery on all of our patients was performed by the same surgeon (JHE) who is an expert in this field, using the same approach and the same type of prosthesis.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that for the purposes of this investigation no human or animal experiments have been performed.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare they have adhered to the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their consent to participate in the study.

The right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Elena J, de la Red-Gallego MÁ, Garcés-Zarzalejo C, Pascual-Carra MA, Pérez-Aguilar MD, Rodríguez-López T, et al. Evaluación de resultados funcionales y Notching tras el tratamiento de fracturas de húmero mediante artroplastia total invertida a medio plazo. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:413–420.